by Dan Talbot | Feb 19, 2024 | Collection, Projects

Rocket 3 Rebuild, Part IV. She’s done!

By Dan Talbot

The legacy of the BSA Rocket 3 lives on among motorcycle enthusiasts, as it was one of the early examples of a high-performance British motorcycle with a distinctive design and powerful engine configuration. Today, vintage BSA Rocket 3 motorcycles are prized among motorcycle enthusiasts and collectors.

Cast your mind back to 1971. I was in primary school, hooked on dirt bikes and pouring over Dad’s Cycle World magazines (except when I found his stash of Playboy mags). I recall peeling through the pages mainly for dirt bike stories but, if I remember correctly, road machines figured most prominently in Cycle World and the British verse Japanese debate was raging. The Honda 750 and Kawasaki 900 were emerging as unbreakable spaceships compared to the aging British machines, such as Triumphs, Nortons and BSA.

I had leaning towards BSA because at that time my most prized possession was a BSA .177 calibre air rifle. As attractive as the BSA bike and the fashion models draped across it were, I was a little vexed because I felt the Triumph Bonneville was a superior motorcycle. This assessment was based solely on my unscientific observation that the coolest dudes rode Bonnevilles.

Five decades have passed since those days and I have owned no fewer than ten Triumphs, including two Bonnevilles. Aside from my air rifle, I have owned only one BSA and right now it’s taking pride of place in my shed. Purchased in August 2018, it’s been a very long journey to getting the motorcycle back to better than new condition. I know that sounds like a big call but I will make my case below, but first I must backtrack a little.

the Rocket was introduced to readers of the Motor Shed in 2019, with Part II published in March 2021 and, more recently, Part III hit the site in March 2022.

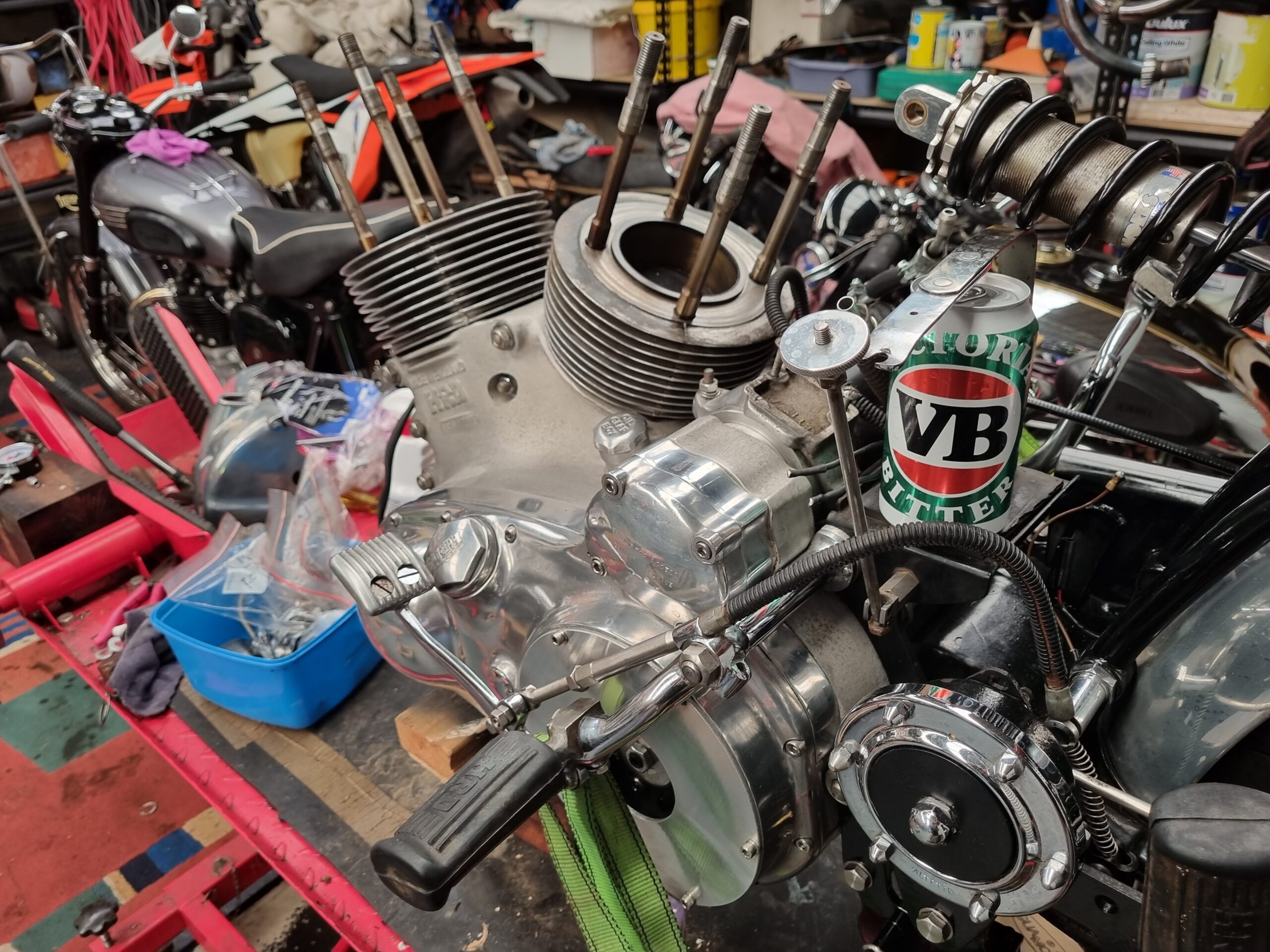

A basket case in the truest sense. This is what we started with!

The restoration has been a five-year journey of industry and hiatus. The industrial component played out in a nexus of time, money and inclination, hiatus occurred when one or more of these positions was challenged or lost. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say this has been an epic job – check out the ‘before’ photograph.

The bike was a basket case in the truest sense of the description. I was, at the time, looking for something a little more substantial but as soon as I saw the BSA, I recognised it as a Rocket 3. Importantly, it was one of the latter, American export versions – there are various names used to describe the Mark 2 Rocket, laziness has me resorting to the ‘export’ designation. To my mind, the exports were the more handsome, if not slightly impractical, version of the Rocket. The tiny petrol tank has limited range, there’s so much chrome bouncing back at you riding on a sun-shiny day can be hazardous and the handlebars may hint at Easyrider but when you’re 6’ 3” tall, they more hinderance than help. I have resorted to UK-style Bonneville bars, the likes of which were on my first ever road-bike – a ’76 Bonny.

At the time of spotting the Rocket, I was in search of a Trident engine. Certainly, there were Tridents in the same shed, some of which were for sale, but my resources would only stretch to one project and I seized upon the Rocket for a very reasonable amount. As it would transpire, seized is a good choice of word. The engine had purportedly been rebuilt in the USA. The certificate of title, issued by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, recorded the milage in June 1975 at 4161. The speedo that came with my bike had 5274 miles on it so one wonders what caused the need for a rebuild. As it turned out, the ‘rebuild’ was more of a rebore, and the pistons had been parked up in the bore for so long, the rings were rusted to the bore. In other words, the rebuild had set me back because the engine was in need of new liners. That was 2018.

The restoration crept along at glacial pace due to competing projects and financial resources. The frame underwent repairs and paint, the tank was re-chromed and painted, wheels rebuilt etc, but the biggie was the engine. I was hearing all sorts of dross about how difficult BSA/Triumph triples are to rebuild and resolved to err on the side of caution. I already had a good relationship with Ben at British Imports in Malaga so resolved to farm the engine rebuild out to them. It was a good, if not expensive, choice. It also took a while but eventually the engine was built. I made a special trip to Perth to collect a sparkling, better-than-new, 750cc triple engine which, incidentally, weighed a healthy 125 kilograms, or the equivalent of a good-sized poddy calf.

I use the calf analogy because getting a recalcitrant beast into a crush, and a BSA 750 engine into a frame, both require three adults, lots of heaving and shoving and can end up with shit all over the place. But we did it. After an hour of struggle the engine was in the frame and the two blokes helping me are still friends.

Along with a complete rebuild, the engine was treated to a new 5-speed transmission, improved oil transfer with a later model (Triumph T160) oil pickup, Trispark electronic ignition and brand-new Amal Premier carbs. Fuel, spark and compression are the essential elements required in the internal combustion engine, hence, electronic ignition and new carburettors are de rigueur whenever I rebuild a motorcycle. In my experience, they are the best guarantee of easy starting and continued running. Ben also talked me into new camshafts and conrods. One night, with perhaps half a glass of shiraz too many, I clicked on an eBay listing for three new MAP Cycle, forged steel conrods and hit ‘buy it now.’ Instantly, I was $1,000 poorer. Poorer still when Ben said I didn’t want those conrods in my engine so they remain boxed up in my shed (fortunately my wife seldom reads my missives).

With the engine back in the frame I hit the bike with new enthusiasm. By that time, most of the paint and chrome had been done. I lost a good deal of time attempting to relace the wheels before sending them off to a professional, only to learn I had purchased the wrong stainless rims of the UK and they were never going to lace up. It’s probably just as well because I wouldn’t want to ride a motorcycle at 120 mph on wheels laced by Dan Talbot.

The last job was the carbs. When Ben received some new stock in mid-23, I quickly loaded the bike up and returned to Malaga. The deal was already in train as Ben insisted on starting the engine and bedding the rings himself. Apparently, there’s a deft science to it and clumsy, backyard mechanics can glaze the bores if they leave the engine idling in the shed for too long. Added to this, had I not taken the bike back to Ben for a start-up, no warrantee would be offered.

There was a litany of small gaffs and foibles on my behalf but, in my defence, this was my first multi-cylinder restoration. I was at the Albany Hill Climb last November when Ben called to list off all the items requiring attention. The worst was my fancy, three into three exhaust system copied from the Triumph Hurricane (another BSA in Triumph clothing). It was brand-new and had me confounded. Likewise, Ben could not make it fit either. We resolved to cut, weld and re-chrome the offending (middle) pipe, which was luckily only one of the three. The chroming alone cost $450!

Eventually, early this month, I got a call saying the bike was running and ready to go. I dropped everything and headed to Perth. When I arrived, I was given starting instructions and kicked the bike into life on the second swing. She sounds absolutely sublime. Any thoughts of flipping the bike to turn a profit evaporated on the ether of a seductive triple bark exiting the faux Hurricane pipes. For now, this one’s a keeper.

by Dan Talbot | May 9, 2022 | Collection, Events, Projects

Things in Graeme’s shed have been developing rapidly since last we spoke: we have life. Sure, it was only a momentary wail in response to a Bendix slap on the buttocks, but just like a parent hearing the first cry of their child, it gladdened the heart of all those present.

The skeleton, with it’s beating heart, is ready for the body.

There was no cranking, and no extra priming of the twin Stromberg carburettors. The electronic fuel pump chattered for a few moments as it pressurised the system then, as soon as Graeme hit the starter, the engine instantaneously burst into life, surprising all those in the shed. That surprise was replaced by deep satisfaction as the 3-litre side-banger, four settled into a contented purr. Presently the exhaust is exiting the collector pipe without any hit of muffling. This is how the car will run at Perkolilli however the beautiful burble will be too much for road use.

Holden six nostalgia comes flooding back with these twin Stromberg carbs.

With no radiator, the experiment was brought to a close very early to avoid cooking the engine, but not before we captured a second burst on video for posterity purposes.

Of all the stages of a build, there is none as significant as a start-up. A major developmental signpost has been passed and the project can move to the next phase. In our case the body was reintroduced to the chassis. This can be achieved by two people, however, there were three of us and we got the body on without causing any scratches. It was at this point where the contrast between the black, heavy-metal chassis and the green of the tinware body, each perfectly complimenting the other.

The newly-painted body is wheeled into the work area ahead for being lifted back onto the chassis.

With the body permanently back in place (LOL), we set about test fitting other body items and within an hour the skeleton and its beating heart were transformed: a stunning green racing machine was revealed.

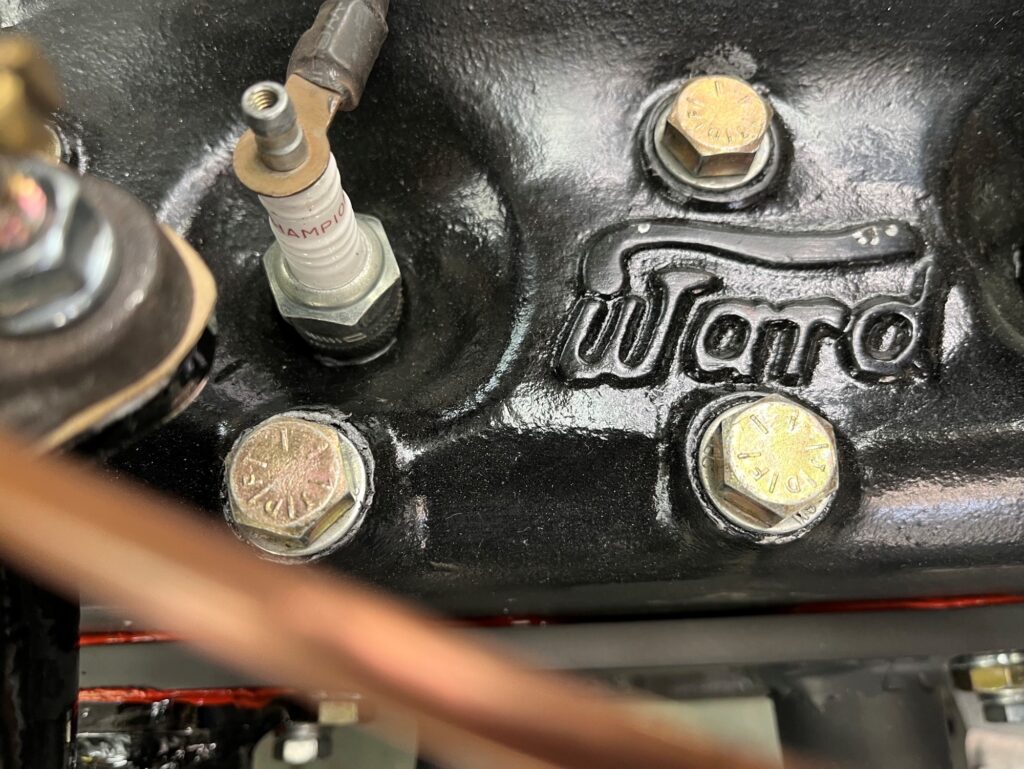

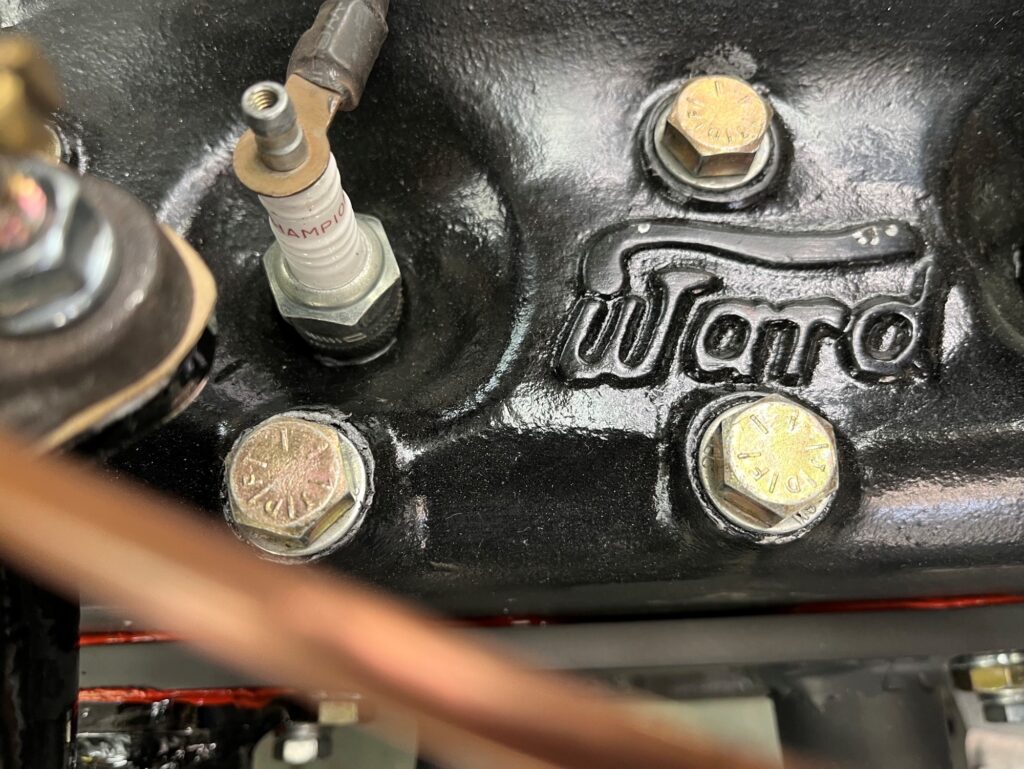

Recall, we touched on the tuned state of the engine in the last piece on Green T? The mods included an early veteran T high-compression head. Well, as Graeme says, you can’t always trust 100-year-old cylinder heads. A few days ago, whilst working on the engine, Graeme noticed an unusual mark on the side of the head. Instigation and a bit of digging revealed a large rust hole. The head was removed and replaced with a very special, and very rare Ward’s performance alloy racing head, cast in Perth by Allan Ward. Graeme has been saving this one for a special occasion. Evidently, its time has arrived. As Graeme says, “that should make this puppy really go.”

Ward high-performance alloy head created and cast in Western Australia.

Finally, before we leave this piece. For some years I have frequently mentioned Lake Perkolilli in the context of a motor racing circuit. I recently came across a passage written by WA Police Pioneer H.E. Graves, who, in 1929, came across the lake on one of his patrols out of Kalgoorlie. Graves describes Perkolilli as, “Surely one of the world’s smaller wonders. Imagine a country dense and chocked with that low, grey-green growth; bridle tracks worming through, an occasional lizard the only company. Out of all this the lake suddenly breaks. It is a huge, roughly circular area of clay. At its edge most unaccountably all vegetation sharply ends. The land becomes dead. The surface of the clay is utterly flat, glass-like, smooth like a mirror. Painfully it reflects the glare of the sun, so that the beholder blinks from its sheen. There must be salt or poison in the land to produce that shining sterility” (Graves, p. 117-118, 1937).

For a more contemporary description, we turn to the Gold Region Tourism Organisation, “Lake Perkolilli is a unique, rock hard claypan which has been the location for many Australian speed records. It was almost forgotten until vintage motor racing enthusiasts returned to bring it to life once again. Lake Perkolilli comes to life before dawn when the coffee p ots start boiling and the smell of frying bacon starts wafting across the camping areas. There is always someone who starts an unmuffled car or bike engine to break the silence. Aah, the music of motors to wake the late risers!”

The Red Dust Revival 2022 medallion has been cast and is proudly displayed on the dash of Green T.

by Dan Talbot | Apr 20, 2022 | Collection, Events, Projects

Out little race special is rapidly taking shape at the hand of master body-builder and engineer, Graeme Lockhart. In fact, it has actually taken shape – past tense. There will be no more cutting, welding, persuading or moulding of the body because it now has a lush coat on British Racing Green – again, by Graeme. Added to this, the chassis has also been treated to a protective coat of POR15.

The engine is back in the chassis and will remain so for now as that too is finished and, barring catastrophes, it will be a goer. Twin down-draft Stromberg carbs, increased compression and custom-made (ie Graeme-made) headers will see the one-hundred-year-old engine produce almost twice the original horsepower. Although, I should add stock was only ever 20 horsepower.

I’ll let Graeme describe what he’s done, “It has high compression pistons and is fitted with an early veteran T high compression head, up from 4:1 to probably 5.5:1. The engine now has 0.030 over-size bore and 12 kg off the flywheel. The crank, rods and pistons have been balanced. Ignition is by distributor and the camshaft is fitted with an aluminium timing gear – advanced 7 degrees. But, apart from that, it’s all stock.”

The heavy Model T flywheel has been relieved of some 12 kilograms.

As I said previously, the trick will be to use the extra power without breaking the crankshaft, the Achilles heal of any hot Model T engine. Then there is getting the power to the rear. The transmission has been rebuilt with new bushes and, where possible, modern materials that will add a touch of reliability, such as kevlar clutch bands. The flywheel has oil slingers added to force oil back to the front of the engine (recall these old engines didn’t have an oil pump, they were lubricated by the crank splashing through the oil in the sump). Graeme has added an external pipe to transport the captured oil forwards and thus aid in keeping the moving parts moving.

In this state, the Model T transmission looks much more modern than its 100-plus years.

The final drive has been rebuilt using a high-speed, racing crown-wheel and pinion that raises the final ratio to 3:1, instead of the standard 4.4:1. This sounds counterintuitive but essentially, the lower the number, the higher the ratio. With a higher ratio the engine turns less per revolution of the wheels and we go faster.

So, what does all this mean? In a nut-shell, this will be a period race car that goes as good as it looks.

The following montage will run from most recent to early stages of the build.

High compression pistons protrude into the combustion space and will add some much-needed horsepower to the ancient engine.

The first coat of the lush British Racing Green has been applied and looks amazing. It will almost be a shame to cover it in red dust!

The engine is back in the chassis and there it will stay, subject to continued good running.

Rear view.

These four massive slugs displace 3 litres.

Twin down-draft Stromberg carbs and hand-made headers are just a couple of mods that will add to the power output. A distributor has been fitted, negating the need for the old Ford trembler coils.

Early veteran high compression head.

Just to revise where we’ve come from.

Seats have been fabricated completely by Graeme.

An early graft of the body, prior to it being widened – twice.

by Dan Talbot | Nov 3, 2021 | Collection

Every time I put my foot down hard at under 40 mph in this muscled Mustang, it sounded like ten vestal virgins being raped simultaneously. Actually it was only the tyres (Bryan Hanrahan, Modern Motor, 1966).

The things you could say in 1966! We’ll get back to Bryan later, for now the Mustang has taken another great leap: we’re on the road. The car has passed engineering with WA Department of Transport (DoT) approval for a modified “high performance” engine, rack and pinion steering, coil-over suspension, improved brakes et al. In other words, she’s totally legal and licensed to thrill.

Aside from the restoration, dealing with and meeting the expectations of the DoT has been tiresome. At the end of this piece is a list of the requirements I had to meet before the car would be considered roadworthy. It should be noted, all of this was because I fitted improved braking, steering and suspension. The components I used had been previously been engineered and deemed compliant with Australian Vehicle Standards Rules. A gazetted engineer had to examine and sign off on all the items on the list. He spent the best part of a full day with me and the car, which included taking it to a workshop equipped with a dynometer to ensure I wasn’t producing too much horsepower. Had I rebuilt and licensed the car in its original form, none of this would be required.

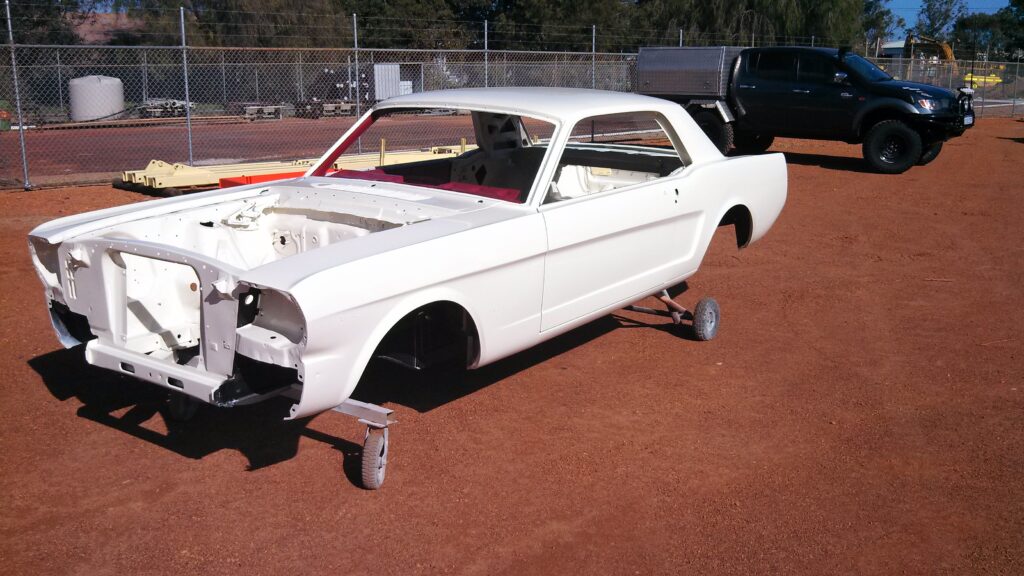

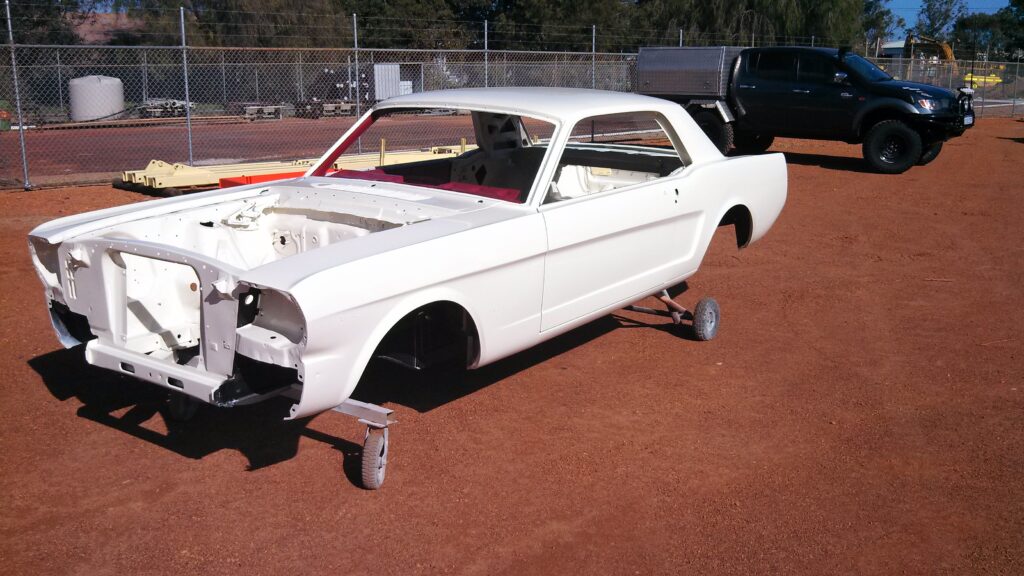

The DoT movement permit has a provision for a number plate. I used “THESEUS.” The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that raises the question of whether an object that has had all of its components replaced remains fundamentally the same object. Such was the state of the original body, everything in this photograph, save the roof, has been replaced.

What started as a transmission rebuild eight years ago grew to a full nut and bolt, rotisserie restoration. Every skerrick of paint and filler was blasted away revealing a very sorry sight, but that’s all history now and the scars of financial pain have diminished. What I ended up with was essentially a brand-new body, with more than half the panels replaced.

The modifications I have carried out on my car probably put it into the ‘restomod’ category of rebuilds. I’m not all that comfortable with the term ‘restomod.’ It’s a contraction of restoration and modification and came out of America where the modifications I’ve made are more readily accepted. In my case it is probably an apt description but I prefer to say ‘make it your own.’ That’s what I’ve done, I wanted to retain the original feel of the Mustang whilst making it safer and more pleasant to drive, and I believe I’ve achieved that. The car tracks beautifully and gives me great satisfaction knowing I’m (kind of) responsible for that.

Recall from the early days, when I said, “One of the defining features of Falcons of the sixties and seventies is the feel of the steering. It was much better than the equivalent offered by Holden and Chrysler but my Mustang was simply awful to steer. Added to this, the transmission was slack and spongy. The car was very much a disappointment.” Well not anymore. One of the reasons the car handled so poorly was the thoroughly agricultural conversion carried out by Ford Australia (Homebush story) way back in 1966. In his 1966 review of the Mustang, Bryan Hanrahan said, “I liked the Mustang. It made me feel ten years younger when I first drove it: it took ten years off my life the first time I tried to corner it hard.” Ironically, original Australian-converted Mustangs, of which there was only about 200, remain the most collectable in unmodified form. But not for me. I wanted something to drive and I was not prepared to live with vague steering and poor braking (fear not, I have saved all of the OEM parts).

RRS steering rack, no longer is the steering vague.

Upgraded brakes provide reassurance.

The DoT insisted I put the car on a dynometer to prove I was not making more than 20% power over normal (it cost me a new camshaft but that’s another story).

By the time I got the rubber to the road, I had an RRS manual steering rack, RRS coil-over front suspension, RRS front strut bracing and RRS disc brakes. The front and read subframes had been connected using aftermarket chassis rails produced for the purpose. I also increased the size of the sway bar from the standard 20mm to the larger 25mm. I may have made a mistake with the manual rack but, that aside, once on the move it feels responsive and reassuring. I did however make a major misstep with the engine.

When I noticed a later (1985) roller-cam 5.0L engine pop up on the market I purchased it, as opposed to rebuilding the original 289. My engine guy built a very strong engine but when I declared the swap to the DoT, they started throwing around the term ‘high performance,’ and that’s when the fight started. The 5.0L engines were released with fuel injection and found their way into a variety of cars, including the Falcon GT. My car had no fuel injection and produced nowhere near the same power as the GT but the DoT err on the upper side of caution and if one variant produces x horsepower, then they all do! It was, for all intents and purposes a fairly standard Ford Windsor V8 engine commensurate with the era. My misstep was using an engine block from 1985, instead of one from the sixties, notwithstanding they were identical. I launched an appeal to DoT and got into a long stoush about the performance capabilities of my engine. Some of which is repeated here;

During the restoration, I learned of a 302 engine for sale in Perth that would negate the need for a complete rebuild to the extent I faced with the existing 289. The 302 engine, whilst still in the Windsor family of engines, proved to be one of the later model, “5.0 litre” blocks which had previously been fitted with fuel-injected. The engine was sold to me as having been ‘refurbished’ in the USA. It was always my intention to use only the short block with the, distributor, starter-motor, carburettor etc from the original car. As it transpired, the 302 required a full rebuild, the corollary being an engine that cost more than rebuilding the original 289 would have been but, by the time I learned that, I was deep into the rebuild and kept going. The car has undergone a preliminary examination by a DoT gazetted engineer. During the examination the engineer said a dynameter report would be required to show the transposed engine was not creating more than 20% of the original power output. The resultant report proved this to be the case.

I had a win but the whole argument was pointless. The dyno report proved the engine did not belong in the high-performance (LA2) category of engines that should have been the end of it. I had to fight the decision as the list of safety upgrades required for the later engine (see below) was completely unreasonable and, in some of the items, unachievable. As I said above, the car had been through engineering and found to be properly constructed, safe and compliant with Australian Design Rules of the era. What I was fighting was the unreasonable assertion my engine was ‘high-performance’ was therefore elevated the car into some unachievable level of finish. I had some very good people in my corner, Graham Billington for one. Had I lost the fight, I would have been consigned to refitting the 289 and running it through licensing with that engine (and possibly even having to revert back to the original steering, brakes and suspension). In hindsight, I should have rebuilt the 289 in the first place. It would have saved so much grief.

Looks like a Windsor duck, walks like a Windsor duck, quacks like a Windsor duck. Must be a Windsor. The Dept of Transport agreed however they also deemed this engine ‘high-perfomance.’ Of course, it was no such thing. Swept volume and dynmeter testing proved as much. Note also the RRS bracing which also had to have engineering approval.

This picture shows the sub-frame connectors being set in place. These pieces link the front and rear sub-frames and give the car extra rigidity.

August 2016. During the refit process, a professional photographer came into my shed and took a few pics. This remains one of my favourites. Thankyou Graham Hay.

Even after the car had been through engineering, it still had to be trailered to Perth for examination. I entered into another long, drawn out battle with the DoT over being able to have my car examined locally. I lost that fight.

On a final note. All of the OEM items remain under my bench with the engine. All the steering, suspension, brakes and braces have been retained for posterity. The hammer-blows of the people carrying out the conversion remain on the shock-tower and chassis rail, as does the quirky, left-hand wiper swipe and the forward-mounted brake booster. If a future owner wants to return the car to the form in which it left the Ford Australia Homebush facility, he or she will be able to do so. In the meantime, I’ll be out there putting the old girl through her paces (as they said in 1966).

The following is a list of requirements I had to meet to allow the car to pass examination;

The Consulting Engineer or Signatory report is to address the following items:

- Consultant to confirm the correct engine number as stamped on the engine block by the manufacture.

- Due to the engine fitment a Mandatory Upgrade of Safety Equipment will be required to include:

- Seatbelts to be installed to all seating positions – retractable lap sash to outer seating positions and lap seat belts to centre seating position.

- Split or dual braking system.

- Windscreen washers.

- Two speed windscreen wipers.

- A windscreen demister.

- Flashing direction indicator lights must be fitted at the front and rear of the vehicle.

- A collapsible steering column must be fitted.

- Fitment and suitability of the (year to be supplied) Ford 5.0-litre V8 naturally aspirated petrol engine in regard to complying with Section LA2 of VSB 14.

- Confirmation of the swept volume of the engine is required. Swept volume test to be sighted by the signatory and results including bore and stroke dimensions to be supplied.

- Fitment and suitability of any modifications to the engine including camshaft, fuel injectors, throttle body, air intake and any ECU programming complying with Section LA4.

- Signatory to provide evidence and engine specifications at time of test to certify that the maximum engine power does not exceed the 180 Kw per tonne power to weight ratio based on the heaviest variant of a 1966 Ford Mustang Sedan.

- A Dynamometer report on the maximum power and torque produced at the wheels after modification is to be supplied. The report must include VIN, engine number, maximum power and torque to be signed and supplied by Consulting Engineer or Signatory to prove compliance. Note: The report must list maximum torque and power on the Y- axis and engine rpm on the X-axis.

- Special consideration should be given to the extra weight applied to the front axle to ensure the manufacturers load capacity is not exceeded.

- The modifications to the exhaust system must comply with Section LA including LT4 (Noise Test) of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the Ford C4 automatic transmission complying with Section LB1 of VSB 14.

- Verification that the speedometer has been tested (and recalibrated if necessary) to the applicable ADR or where no ADR is applicable an accuracy of +10% or – 0.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the body/chassis modifications including engine and transmission mounting and fitment complying with Section LH of VSB 14.

- The total body/chassis structure and driveline being capable to sustain all of the stresses that is likely to be experienced by all of the proposed modifications.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the right-hand drive steering conversion complying with Section LS1 and LS2 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the RRS Rack and Pinion Steering conversion complying with Section LS4 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the modified suspension complying with Section LS of VSB 14.

- Evidence is required to verify the suspension travel is not reduced by more than one third of the manufacturer’s specifications.

- Special consideration should be given to ensure regulated height and ground clearance requirements are met.

- The consultant’s report is to supply the OEM and modified eyebrow and roof height dimensions.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the body/chassis modifications including chassis strengthening complying with Section LH of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the modified braking system (if other than total OEM option) complying with Section LG1 & LG2 of VSB 14.

- A brake test will be required for this vehicle as per LG1 Design Approval, refer to Table LG4 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the wheel track, wheels and tyres complying with Section LS of VSB 14.

- The wheels and tyres specified in your application appear not to comply with the LS section of VSB14 (overall width & diameter) and therefore are unacceptable. The LS section of the code fully explains the requirements. It is suggested that VSB14 be referred to and consultation with an Engineer to select wheels and tyres that meets the requirements of VSB14.

- A weighbridge docket verifying the vehicle TARE weight is required.

- The total body/chassis structure and driveline being capable to sustain all of the stresses that is likely to be experienced by all of the proposed modifications.

- Any other test or report that the consultant may consider necessary to prove conformity and safety of the modifications.

Please Note: Any modifications that are performed to the vehicle, additional to the original application will require a complete, new modification application to be submitted for re assessment. 5 of 6 Vehicle Safety and Standards 34 Gillam Drive Kelmscott 6111 Telephone (08) 92168579. Email: tps@transport.wa.gov.au

Note: This letter and the copy of your application are to be shown to your Consulting Engineer or Signatory, so he is aware of the items to be addressed.

Consulting Engineer or Signatory report is required to coincide with the application submitted by owner or agent. Time delays will be incurred, and the possibility of a new application will be required for the modifications by the owner or agent.

- Approval in principle to modify is granted at this point; however final acceptance cannot be completed until an acceptable report is submitted to DoT, Vehicle Safety and Standards Section for assessment and approval.

- This approval in principle for modification of the vehicle is valid for two years from the date of this letter; the Technical Policy and Services Coordinator must approve any further extension of time in writing.

- The report must include the name and address details of the applicant, vehicle details e.g. Make and Model, Year, engine, transmission, vehicle identification number, engine number and the Vehicle.

Special thanks must go to Graham Billington of Ultimate Automotive in Bunbury who came to the rescue when, having received the above letter, I tossed my toys out of the cot and and threatened to sell the finished car – unlicensed. Graham called me and, through the art of gentle persuasion, made me realise I had come too far to give up. I’m glad I persevered, thanks Graham. Now I’m off to find ten vestal virgins.

The car is registered on the WA Concessions for Classics (C4C) licensing scheme. This is much less restrictive than the former (404) scheme and allows us to use the car for special treats – such as a date night at a local restaurant.

by Dan Talbot | Aug 19, 2021 | Collection, Projects

Some time ago, actually, a long time ago, I wrote a piece about a race car intended to hit the red clay pan of Lake Perkolilli that was under construction by my friend Graeme. In the story I promised to revisit the car when it was finished. I didn’t. Let me finish it now and also introduce the next car under construction by Graeme.

Both of these cars are based upon the Ford Model T platform. Graeme loves the Model T with a passion. He is also a qualified mechanic and somewhat of an amateur engineer. Add a dash of artistic flair and you can begin to appreciate the skills this man possesses.

So, back to Graeme’s black T. Graeme’s racer was created in the format known as a “Gow Job,” which apparently comes from “gowed up” (Hiedrick, 2014). These home-built speedsters typically started with a Ford 4-cylinder, presumedly due to the ubiquity of the humble Model T. Hiedrick states these engines had a top speed of 55 to 60 miles per hour, which, as the owner of a veteran 4-cylinder Ford, I find rather ambitious. “To increase this top limit, a gow job mechanic would remove anything unnecessary – fenders, bumpers, windows – to improve the power to weight ratio” (ibid).

Last time we saw the black gow it was devoid of wheels and paint. To recap, the racer is powered by a 3-litre, 4 cylinder, mounted on an original Model T chassis that has been lowered some 10 inches. As is often the case with projects from the distant past, Graeme only had bits and pieces of a body. For the pieces he was missing Graeme used his unique CAD (cardboard aided design) templates to first fashion the required part and fit it against the body before creating the panel in metal. All the bright metal in the accompanying photographs has been fashion by Graeme, by hand.

Here’s one he prepared earlier. Another journalist referred to this car as a “Gow Job” which sent me searching for the meaning of such a term.

Beautiful from any angle.

Naturally, the black gow was finished and triumphed at the 2019 Perkolilli event. That event was covered by me in another publication (because they pay more than I do). It can be viewed here. The racer clocked a top speed of 126 km/h on the chopped up red dirt. Not bad for an engine built in 1925 with 20 horsepower. Graeme is going for broke now with an engine which he is hoping will yield a top speed of 160 km/h – which is the old ton, or 100 miles per hour. The ton was quite elusive in the nineteen twenties so racers had to be resourceful to break it, frequently breaking the engine and/or car in the process. In true racer endeavour, Graeme has built an engine which I suspect will give the ton a good nudge. More about that engine later, for now we shall look at where the 2019 Perk engine is going. Enter Green T.

The narrow Aston body fits the Model T chassis quite nicely, although the cockpit remains a little cramped at this point. Note Graeme’s cardboard aided design.

Boat-tail rear.

Green T started out, as the name suggests, as a Model T. Actually, a conglomeration of Model T parts Graeme has collected over the past few decades. A glace around his very well organised shed suggests he could build several more. As alluded to above, the race-proven engine will be mounted into one Graham’s expertly fabricated, lowered and modified race chassis. It will then be fitted with an Aston Martin body, more particularly a body from an Aston Martin. It is unlikely the body was actually made in the Aston Martin factory but it has seen service on a very special Aston Martin racing car that was brought to Australia for the 1928 Australian Grand Prix.

The Aston was a lithe, alloy-bodied, open wheeler GP car from 1922 or 23 (it’s not exactly clear). It was powered by supercharged 1486 cc side valve engine of Aston Martin’s own design. Incidentally, Lionel Martin’s partner in their fledgeling automotive manufacturing business was Robert Bamford. The name Aston Martin comes from a celebration of the success Lionel Martin enjoyed at the Aston Clinton Hill Climb in Buckinghamshire, England driving a car of his and Bamford’s creation.

The men went into production and began selling small numbers of their cars, possibly as few as 55, three of which are known to have been brought to Australia. One of the three cars was purchased by Mr John Goodall and evidently had a successful history of racing in Australia, including being driven by Mr Goodall on the first Australian Grand Prix, a 100-mile event at the Phillip Island circuit in Victoria in 1928. The car failed to finish in ’28 event but was entered again in 1929 and 1930, finishing third in the latter event, which by that time had grown to 200 miles.

In 1977 the car was purchased from the Goodall family by Mr Lance Dixon. It turned out much of the alloy components of the engine had been melted down for armaments during World War II. However, another engine, from one of the original three cars imported back in ’27, was located by Mr Dixon, powering, of all things – a boat. The engine was fitted to the remnants of the Goodall car and a body was remanufactured out of steel. The small race car remained with Mr Dixon up until 1982 when it was purchased by Mr Peter Briggs for display in the York Motor Museum and, later, the Fremantle Motor Museum.

Under Mr Briggs’ ownership the car under went a full restoration which included a new aluminium body. The builder of the body flew from Perth to the UK with the sole purpose to measure and record one of the original GP Astons to ensure authenticity of the reconstruction.

Peter Briggs’ Aston Martin after it had been returned the original style of the all aluminium body. Photograph by Mr Holger Lubotzki.

The steel body was stored first behind the York Motor Museum before being moved to the Veteran Car Club of Western Australia parts store in the Perth suburb of Wattle Grove. And that’s where Graeme found it. So, to take stock, we have enough parts to build another Perkolilli racing Model T, a body from a famous Australian racing Aston Martin and a very talented mechanic slash engineer. Some twelve months ago, Graeme began construction of Green T, the name paying homage to another famous racing Aston known as “Green Pea.”

With the same owner now since 1958, this well-known 1922 Aston Martin is affectionately known as Green Pea. It is of similar pedigree to the car imported by John Goodall in 1927.

The Aston body T has been cut, tucked and moulded into the what is clearly going to be a very special race car. To be honest, the body looked a bit odd on the Aston Martin chassis. It sat up high, was cramped and carried odd lines that departed somewhat from the racing stance of the original Aston Martin machines. Graeme has widened the car and remanufactured the cowl, both raising and lengthening it. The result is two humans can now comfortably sit in the car (including yours truly who is 6’ 4” in the old scale). These mods have added style and flair befitting a car of the era.

The Aston competes at the York Flying 50 C1982, prior to its aluminium upgrade. Note how high the body sits and the way the passenger is skewed to the right. Graeme has overcome both of these issues.

Again, the Aston still with the steel body fitted.

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.

Widened in the beam, Green T will now comfortably seat two full size human beings.

by Dan Talbot | Mar 16, 2021 | Collection, Events, Racing

“Norton owners like nothing better than pulling their engines apart on Sunday afternoons (Donald Heather Man. Dir. AMC 1954-60).

With the greatest respect to Donald, some Norton owners actually prefer to be riding their machines, such as those who gathered in Donnybrook, Western Australia over the 13th and 14th of March, 2021. In excess of 40 Norton owners assembled for two days of riding, nattering about and admiring Norton motorcycles. Not just any Nortons mind you, this was a gathering of Norton motorcycles with only one cylinder. These folk think nothing better than riding their motorcycles on a Sunday afternoon however, given the last Norton single was manufactured in 1964, there’s plenty of afternoons spent pulling engines apart.

Donald Heather’s utterances were nothing more than motherhood statements designed to appease investors who, in 1960, were growing nervous with the lack of future direction the exhibited by the company. Rumours of unreliable and fallible machines were quelled by Heather as he fought to hang onto his lucrative position. The remedy proved to be a series of twin cylinder machines and, presumedly, the appointment of a more passionate and dedicated executive who would remain faithful to Norton’s heritage. However, by then, it was too little, too late. Norton twins were a fine machine but the company only managed to hang by its bootstraps. Gone was the racing heritage and successes that defined Norton’s early years.

1910 was Norton’s second year with his own engine. Only seven of these machines are known to exist in the world, here are two of the seven at the same event in Donnybrook, Western Australia.

Norton Motorcycles was established in 1898 by James Lansdowne Norton. Norton was a gifted engineer but a poor businessman and the company fell into receivership early in its life. This would signal the future for a manufacturer who was more concerned with performance and reliability than returning dividends for shareholders. Competing with the liquidity of Norton Motorcycles, was James Norton’s health. He fell ill as a young man and was left with a malady of premature aging, earning the young engineer the nick-name “Pa.”

Pa Norton was only 55 years of age when he passed away and sadly did not live long enough to witness the legacy of his creation – namely the most successful single cylinder motorcycle of all time. I can hear Ducati riders spitting their Chianti back into glasses everywhere. Whether, or not, Norton is the greatest motorcycle of all time is an argument best left for campfires, dining room tables and Christmas day punch-ups with the brother-in-law. What can’t be disputed is single cylinder Nortons are achingly beautiful motorcycles with performance to match. It’s no accident Norton dominated racing across the UK and Europe for the first half of the twentieth century. Ten Senior TT wins between 1920 and 1939 and 78 out of 92 Grand Prix races are impressive statistics in anyone’s language (including Italian).

In 1924 Pa Norton, suffering advanced cancer, was wheeled up to the main straight of the Isle of Man TT circuit to witness his motorcycles take out two TT trophies that year. Pa received the great chequered flag of life on 21 April 1925 and has been venerated ever since. By many people, including me. My trials and tribulations are well documented on this site and elsewhere, but, still I remain a faithful follower of the brand.

Muz and Rocket, two Norton enthusiasts the author is honoured to call friends.

This brings us neatly to the inaugural Norton Singles Run, hosted by the Indian Harley Club of Bunbury, Western Australia. The run, hatched by Norton enthusiasts Murray, Peter and Kelvin, was scheduled to take place in February was postponed when WA went into a Covid-enforced lock-down, throwing plans into disarray. Had it not been for the Covid factor one would expect many more motorcycles, however, by any measure, the inaugural event was a huge success. The line-up of machines on display was breathtaking. ‘Line-up’ is probably the wrong word, getting this mod to form anything resembling an orderly assembly simply for a photograph was not on the agenda. These blokes wanted to ride Nortons, talk Nortons and look at Nortons. Consider, there are seven 1910 Norton motorcycles know to currently exist in world. Two of them were present at the Norton Singles Run. 1910 was Pa’s second year of production with his own engines. Up until this time he had been using proprietary units from Swiz and French manufacturers. It was a Peugeot V-twin engine that powered Norton to victory in the first ever Isle of Man TT races in 1907. That was the last time Pa Norton would dabble in twins, as far as he was concerned future victories lie in the simplicity of singles. The rest is, as they say, history.

Another profile of the pair of 1910 Nortons. This one by Alan Wells.

One of the lovely ES2 Nortons that were in attendance at the inaugural Norton Singles Run in Donnybrook, Western Australia. Photograph by Alan Wells.

Another ES 2, this one from 1935. Pic by Alan Wells.

A line up of achingly beautiful Norton motorcycles. These ones are from 1924 to 1926.

Event organiser, Kelvin, wasn’t letting crutches prevent him participating in the ride.

Greg on his stunning ES2.

The 500cc 1910 Norton was getting along at a fair clip. Here she has just climbed a hill that would have a modern motorcycle looking for a lower gear – which is not an option for Andrew, he only has one.

The South West of Western Australia provided the ideal location to get about on vintage and veteran Norton motorcycles.

Manx silver, as far as the eye can see.

Saturday lunch stop was the Wild Bull Brewery in Ferguson Valley, Western Australia. A highly recommended venue.

Event organizer Murray on his 1929 CSI Norton 500, photograph by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography.

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.