Back in October last year I helped out as a marshal at WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally hosted by the Indian Harley Club. I enjoyed my roll as Clerk of Course, not least because I got to spend a whole week touring the South West of Western Australia on my ’48 Vincent HRD – which is by no means a veteran motorcycle.

Subsequent to the event, my friend, and fellow IHC club member, Des Lewis released a very good quality video of the rally (WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally 2021 – YouTube). Such is Des’ prowess with the camera, at the end of his video, my wife turned to me and said “you should get one of those.” “Okay, challenge accepted.”

Veteran motorcycles rarely come up for sale and, when they do, they generally cost a few bob. An added complication is I have a particular hankering for a v-twin. The ones I have gravitated towards start at about $75k (AUD) and go up from there. It may surprise a few readers that I don’t have a lazy $100k waiting for the right veteran motorcycle to come available. I do however have the connections and ability to rebuild a project machine. A machine that will still start at about $20k for a v-twin. If I am going to get onto a veteran Excelsior, Yale or Pope, I will need a fairly decent starting wedge. I will need to sell something. I resolved to swing back to the Rocket 3 project (part 1 can be viewed here and part 2 here). That job has been parked up whilst I have been busy elsewhere. The fly in this ointment is: I am telling myself this is a rebuild that will be offered for sale.

Long before Triumph named their 2.3 litre behemoth the Rocket 3, almost 6,000 BSA’s Rocket 3 motorcycles had made their presence felt on the racetrack and in the boardroom. These bikes were manufactured from 1968 to 1972. Their Triumph stablemate, the Trident, lasted a little longer into the mid-seventies.

My once grand 1971 Rocket 3 came to me as basket case of forgotten dreams. A relic of its former self, certainly not something befitting the victory in the 1971 Daytona 200 or the machine that was able to conquer Agostini’s MV at Mallory Park in the same year. Two frames were thrown into the deal, from which I was be able to salvage one. The bike had clearly been crashed, big-time. Despite being an obvious write-off, the assembled parts arrived in Australia with a title and import approval. It had been uncovered by a friend who lived and worked in the US for about seven years. Like me, Steve has an unhealthy attachment to triple cylinder British bikes, namely, Triumph Tridents and BSA Rocket 3 cycles. Every time Steve saw a triple come on to US the market for under $2,000USD he would snap it up. During his seven years, Steve amassed some 14 motorcycles, two of which now reside in my shed (you will note I’m referring to the basket case Beeza as a motorcycle). Alarmingly, he still has a container full of bikes in West Virginia awaiting dispatch to Australia, some of which will no doubt end up my shed. Back to the pile of rubble.

During some cut and tuck between the donor frame and the crashed one, we had cause to cut the head stock from the frame. Only then, one can see how thick the metal tubing is. It’s massive. Looking again at the bent tubes and thinking about the forces that would be required to bend it are a little bit mind boggling. I doubt the person who crashed it would have survived. There was some serious impact there.

Two frames become one. Note the bends around the head stock. This frame should have been grey, instead, it had been repainted in a blue metallic finish. It also had the two down tubes replaced at some time, causing me to suspect it had been crashed twice.

The repaired frame has been resprayed in a lush black paint. I did consider powder coat but paint much closer resembles the original without the chunky, plastic-coating quality powder coat produces. Whilst the frame was in the paint shop, I turned my attention to the guards. The later Rocket 3 incarnation, starting in 1971, has acres of chrome, including the tank and guards. The chrome and bling came out of BSA Triumph recovering from a design misstep. Actually, history shows there were quite a few missed steps.

During the frame reconstruction, we had cause to cut the top tube. This is how thick in is!

The BSA and Trident 3-cyclinder, 750cc engine is almost identical. The engine was originally a Triumph design however, BSA had acquired ownership of Triumph a dozen or so years earlier and, whilst they were separate entities, operating out of separate premises, BSA decided they wanted a piece of the triple action. Prototype machines were being tested in 1965 and could have gone into production for the 1966 model year. Simple badge-engineering should have done it however, not content with sharing the design across the two brands, BSA insisted on making a triple of their own and this is where things get a little ridiculous. The Triumph triple cylinder engine was built in the BSA factory at Small Heath, it was, for all intents and purposes a BSA engine. In following naming conventions of the day, engines destined for Triumph were stamped with the prefix T150. BSA engines were stamped A75. That’s easy, no problem there, except to see the difference between the engine prefixes one almost needs to get down on the ground to read the stampings.

The engine that started it all: the Triumph T150 750cc triple. Designed by Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele. Photograph supplied by Leonard Johnson.

It was decided the BSA engine would need a distinctive look so the barrels on the BSA unit were canted forward by 13 degrees, which (kind of) dissociate them from Triumph. The right-side timing and gearbox outer cases were also altered to provide another individual touch to the BSA item. Think of designing something that is basically the same yet requires re-tooling, casting, machining etc and the simple act of making minor changes becomes a major undertaking. Luckily, the internals remained the same between the two engines, as did just about every other piece of the triple.

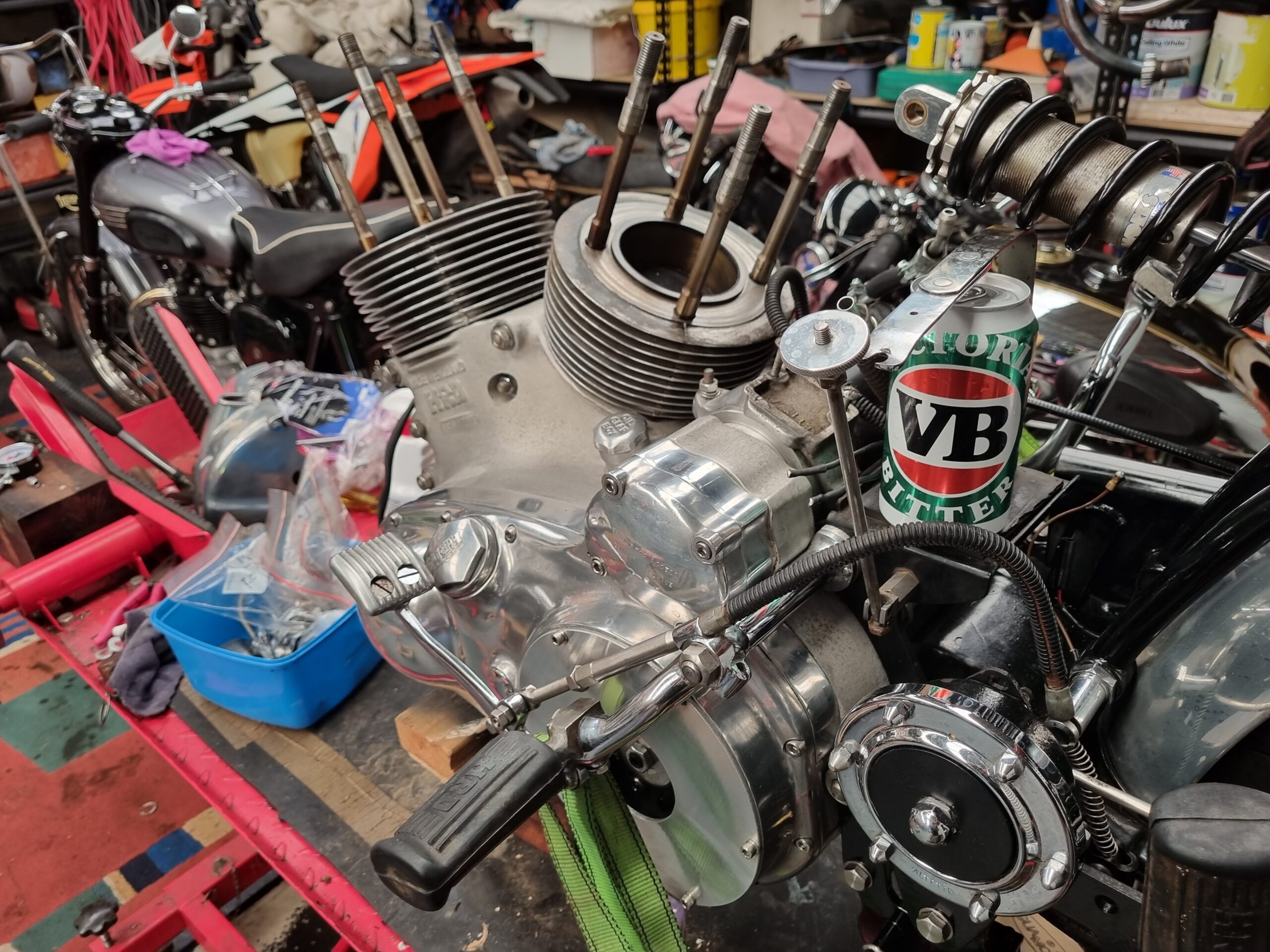

My BSA Rocket 3 engine prior to stripping. Although not immediately apparent, the barrels on this engine are canted 13 degrees forward (as opposed to the Triumph T150 engine). Subtle changes to the timing case are also evident, otherwise both engines are essentially the same.

With the engine (almost) uniquely styled to BSA, it became apparent the Triumph duplex frame would not support the forwarded slanting engine so the BSA would need a new frame too. Conveniently, Triumph would later use the same set up to allow inclusion of an electric start behind the barrels of their 1975 T160, which would become the last of the triple cylinder Triumphs.

The finished product would add two years to the release of both bikes and BSA Triumph missed the opportunity to unleash the first mass-produced, multi-cylinder superbike onto the world market. Instead of releasing their world-beating machine in 1966, it was released in 1968, mere weeks before Honda came along with their new 750/4. The Honda Four was almost as fast as the British triple but was less expensive and would prove to be more reliable than the BSA Triumph offering. The Brits had been caught resting upon their laurels. They were the motorcycle super-power of the time and probably expected to remain as such. As touched on earlier, Triumph and BSA triples went of to win production racing around the world, including the two most famous races of the time, the Isle of Man and Daytona. BSA dominated the American AMA competition well into the 70s but sales of the Japanese bikes sored, whilst sales of the British machines stagnated. Aside from the expense of the British machines, they had a distinctive style that did not go over well with the buying public.

To celebrate the release of the new machines BSA/Triumph engaged Ogle Design Company headed by David Ogle. Ogle Design were known for creating the Raleigh Chopper bicycle, toasters and an odd little three-wheel motor car by the Reliant Motor Company. In 1968 they entered the two-wheeled world when contracted by BSA/Triumph to put the finishing touches to their new triple cylinder motorcycles. It was a disaster. The famous lines of the Triumph twin, one of the most iconic motorcycles of all time, were lost. In its place was a slab-sided fuel tank, massive side covers and futuristic mufflers – referred to these days as ‘Rayguns.’

The Ogle Designed first incarnation of the BSA Rocket 3. Quirky at the time of release, these machines are now highly sort after.

Note the ‘Raygun’ exhaust. Considered a bit odd at the time of release, there mufflers are now very much sort after. Photograph by Tim Hesford.

The new machine was a hit with road-testers and racers but it failed to win the hearts and minds of Triumph owners, and potential owners. Motorcycle journalist Bruce Main Smith described the Rocket 3 as: “Biggest and most beautiful hunk of reciprocating machinery ever built.” It would take two years before the Ogle hoodoo could be undone and BSA/Triumph returned to the tear-drop tank, high bars and megaphone style exhausts. The new machines were released in 1971, predominately to the US, gaining unofficial title as ‘Export’ models. It is this variant of the BSA Rocket 3 that I am bringing back to life.

By 1971, BSA Triumph began to offer an alternative version of their machines designed to appeal to US buyers. The machines were dubbed ‘export’ models. This motorcycle is owned by Warren Hodder in New Zealand. The photograph has been supplied by Warren Hodder.

Note the Dove Grey colour of the frame. This wasn’t received all that well and by the end of ’71 BSA had gone back to a black fame. Photograph by Warren Hodder.

As each gleaming piece returns home and is stored or, in a few cases, refitted to the bike, I become just a little more attached. It’s like getting a kitten. The attraction is based first at a cute, superficial level but grows each day until the kitten becomes a cat and is loved very much as part of the family. Similarly, the BSA is starting to edge its way into my heart. It is going to be a special motorcycle and, as such, I throw only the best quality parts at it, such as forged steel conrods and chrome-plating that seemingly has no end. I could get cheaper, knock-off items from India but I want to retain the original items, even if it is more costly (just in case I end up keeping the bike).

Paying for the re-plating of a motorcycle that was lavished in chromium is arduous. I send parts to the platers piecemeal, so as not to shock the wife with too large a debit in our bank account. The guards cost $500 to replate. It sounds like a lot of money but the finished product is magnificent. The new chrome guard tucked in the black frame looks splendid. The next instalment of pieces for the chrome-plater are on their way.

Also on their way to the platers are all the fasteners and ancillary pieces that I had previously re-finished in zinc. This was a mistake. As the project has been parked up for a couple of years the zinc has discoloured and cannot be put back on the bike in the present state. I will now have them re-plated in cadmium (like I should have done in the first place).

This lot are going back to the electroplaters to be redone in cadmium. Which I should have done in the first instance.

On a final note, and going back to chrome, the Export model fuel tank was chromed and painted – not unlike the Ariel I have just finished and reported on in last month’s Classic Vibrations. Organising a union of chrome and paint is difficult in WA. Platers charge enormous amounts and they can take months to be finished. For some years, whenever I’ve needed chrome and paint, I visit John Berkshire, the former owner of Vintage and Modern Motorcycles. Vintage and Modern had a premises in the same block of units as K & D Metal Finishers and John has maintained his connection with Kerry from K & D. The result being, I have a one-stop service that turns out first-class paint and chrome products. To this end, I now have a beautiful orange and chrome tank waiting to go back onto the motorcycle.

The second lot of chrome has been completed. The first being the fuel tank, the third lot was the guards and the fourth is about to be sent off to the electroplater.

The fourth, and hopefully final, lot of parts are off to be re-plated. In most cases these items could be obtained as reproduced pieces out of India but I feel better using the original items – even if it does cost a bit more.

Fresh chrome on lush, black paint.

Special thanks to Tim Hesford, Warren Hodder and Leonard Johnson for supplying photographs of their motorcycles.