by Dan Talbot | Mar 12, 2021 | Collection, Projects

Forgive me readers of the ‘Shed for I have been a bit slack of late. It has been some months since I last put my pen to paper, so to speak. In my defence, I have been a wee bit busy writing a 100,000-word thesis which is now with examiners in the UK. So obscure was my topic, we couldn’t find people qualified enough in Australia to pass judgement on my doctoral scratchings. Anyway, back to the shed.

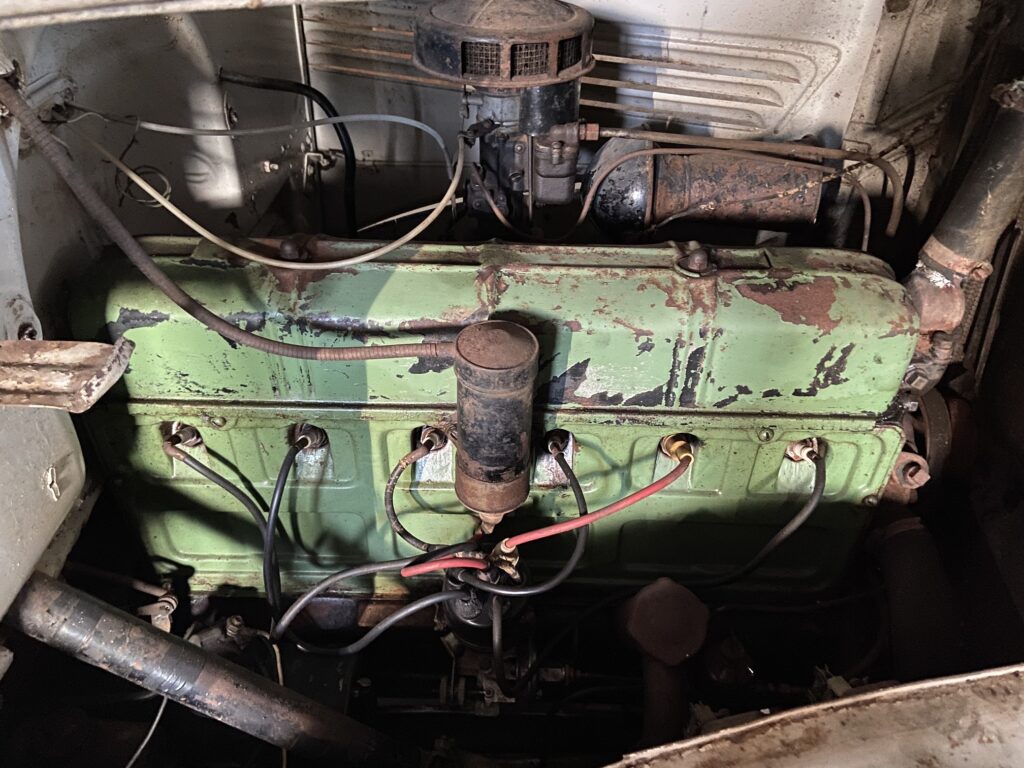

There has been a bit on, the most significant being we have a new inclusion to the ‘Shed. On Christmas Eve, we picked up a 1938 Chevrolet half-ton truck. In trucks terms, it’s very small, more like a flat-bed ute. It is licensed and running, but needs some serious work. The little truck was built in Australia from an engine/chassis imported from Chevrolet USA and built up according to Australian demands, which, at the time were many. Clearly, however, power wasn’t one of them. Driving the little truck 60 kilometres to home was laborious. She was flat out doing 40 miles per hour and for a time, I became more of a nuisance than the mortal enemy of motoring enthusiasts everywhere – the caravan.

The Chevy has been purchased by Catherine for her honey business and will become both a practical and promotional vehicle for Wedderburn Honey. Affectionately known as “Honeycomb,” the first order of business is restoring the bodywork, followed by giving her longer legs (the truck, not my wife). Both of these undertakings are easier said than done.

In terms of the first undertaking, as I write, all the tin-wear is off the chassis and is with the painter. The guards have been finished and the running boards are almost done. The cab is a bit trickier but for a truck of some 82 years of age, it’s in remarkably good condition. I trust the photographs accompanying this story will add credence to my assertion. Some folk will look at the photos and quickly start bleating about patina and leaving it as it is, and so on. Let me stop you right there. My wife and I are of the opinion ‘patina’ is a euphemism for being too lazy to go to the trouble of panel and painting. Aside from this, the so-called patina in the photographs is not original. Unearthing body panels revealed the original colour, an olive gold, and it is to this we hail. Giving the car some beans is equally fraught with complexity.

At a time where every man and his hound are putting V-eights into classic Chevs, we are breaking with tradition and sticking with the straight six, or “Stovebolt” as they are affectionately known. The original, 1929 Chevy sixes were held together with bolts that apparently looked like they had been lifted from wood-burning stoves, hence the name. Stove bolts have long since been dispensed with, but the name has stuck with the venerable donk and now there is a renaissance of the humble Stovebolt taking place across the USA which, one would expect, will arrive here in due course. And we’re ahead of the play because we’ll be running a stonking big Stovie. A 292 in fact. The 292 cubic inch engine will be coupled with a Muncie four speed truck box – Catherine insisted on a truckie’s manual gearbox and it is her truck. Behind the gearbox will be an Aussie Holden, one-tonner diff with a 3:1 ratio.

Whilst we’re on Holden. Our truck originally arrived in this country in February 1938 as a knocked down, Chevy engine and chassis. In the decades preceding the Great Depression, the craftsmen and women of Holden body works had earlier busied themselves with making saddles before progressing on to motorcycle sidecars. In true ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ Holden turned to automobile bodies during World War One and emerged with a workforce skilled in auto body construction. The rest is, as they say, ‘history.’ We possess a little piece of that history and here it is.

Be sure to check in on our Facebook page, Honeycomb the Truck, for more frequent updates on the progress of our restoration https://www.facebook.com/Honeycomb38Chev

The interior of our ’38 truck. Basic, bare and beautiful.

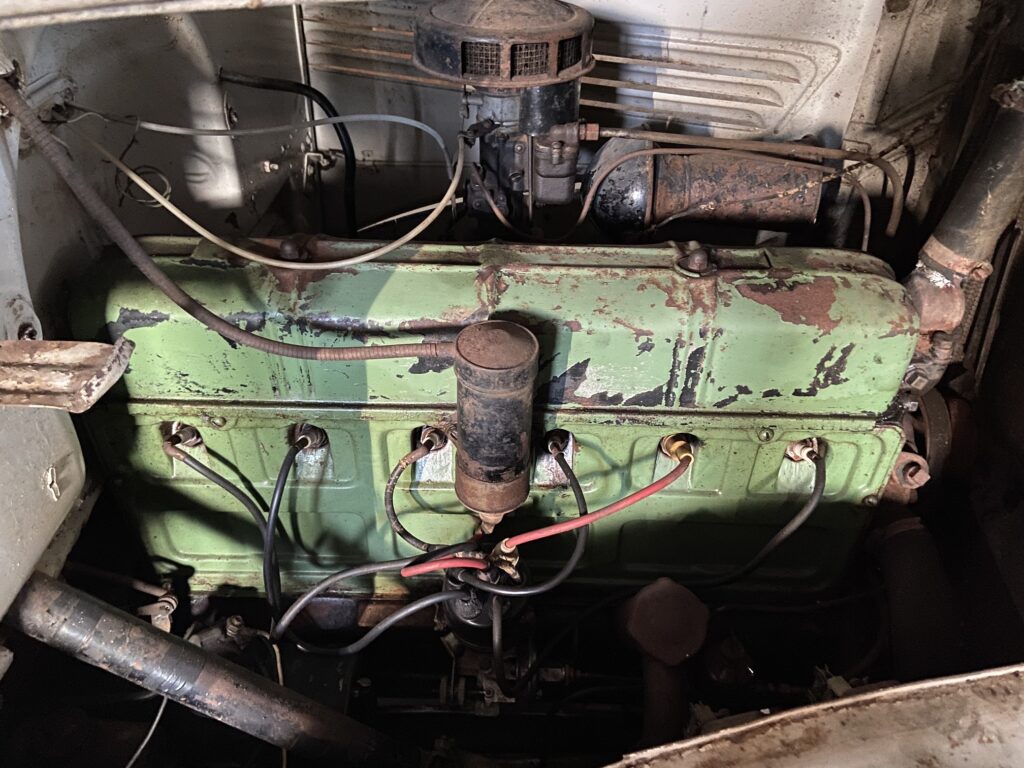

The venerable Chevy Stovebolt six. This one will be replaced with an engine that will propel us down the highway at the same speed as the rest of the traffic.

Body by Holden.

Unmistakably Chevy. The ’38 still bears the plates of its former home, Kulin, in the Western Australia Wheatbelt.

We would like to think the timber that makes up the buckboard rear of Honeycomb is original. We plan on re-using as much of it as we can.

Disassembly of the little Chevy truck commenced within weeks of her arriving at our home. Note the shades of the original olive gold beginning to emerge, having been hidden since the last re-paint.

Catherine finds a nice place to hide.

Word from our body and pain man filtered back home “Keep Dan away from that gas-axe.” Evidently I was burning away more than just rusty old bolts.

As we whittled away various body parts, the value of a life spent in the wheatbelt become apparent. Rust was minimal of an 82 year old lady.

By 1938 brass was so last year. The world was turning onto chrome plating and beautiful brass was being hidden. Not any longer. We have revealed quite a few brass pieces that have been covered by pain or chrome. They will be polished and displayed in all their original glory. This hubcap is an example.

A sneak preview of things to come. Some pieces have already begun to filter home.

Still in the Stovebolt family this larger engine will give the little Chevy the long legs she needs.

by Dan Talbot | Dec 7, 2019 | Collection, Projects

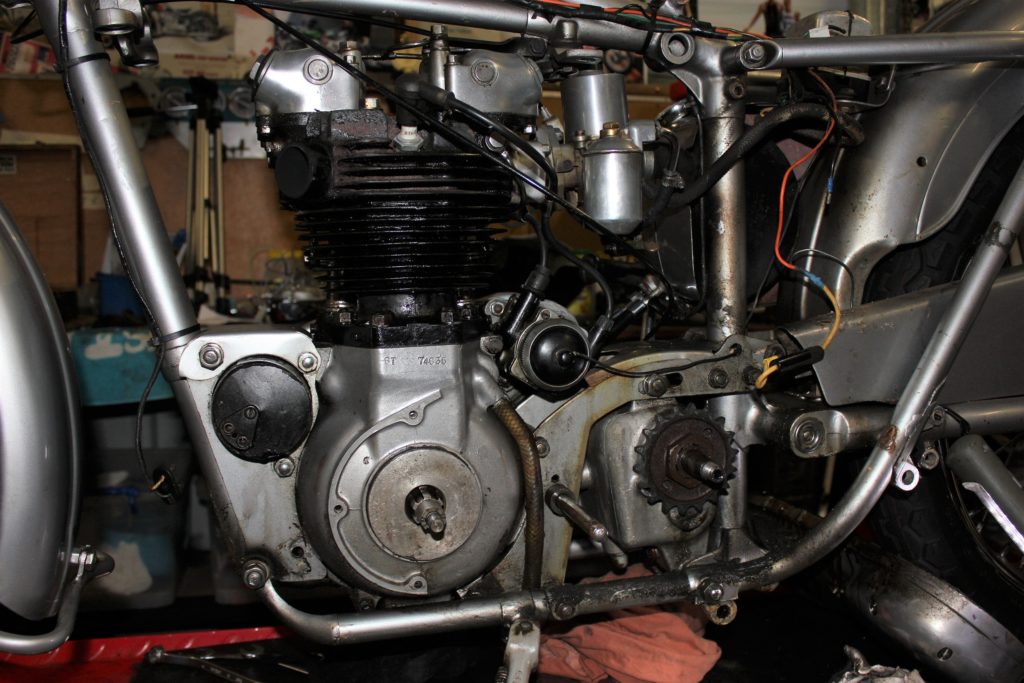

When we left off with the last instalment, the little Norton was parted out here, there and everywhere. Readers and interested parties will be happy to know most of those parts have been renewed and, if not back together, they’re at least back in the shed. One such ‘part’ is the engine.

For a 350 cc machine, the engine in the little Norton is a substantial lump of iron and alloy. This is understandable as essentially the engine started out as a 500, only the internals are different. In fact, the whole bike is basically a 500 ES2, albeit with 350cc. This actually makes it quite rare. By the mid nineteen-fifties young men in the UK were craving larger capacity machines and would overlook the M50 in favour of its big brother. Many of the 350 cc bikes that were purchased had the single cylinder engine taken out in favour of a larger twin, such as that found in the Motor Shed Triton.

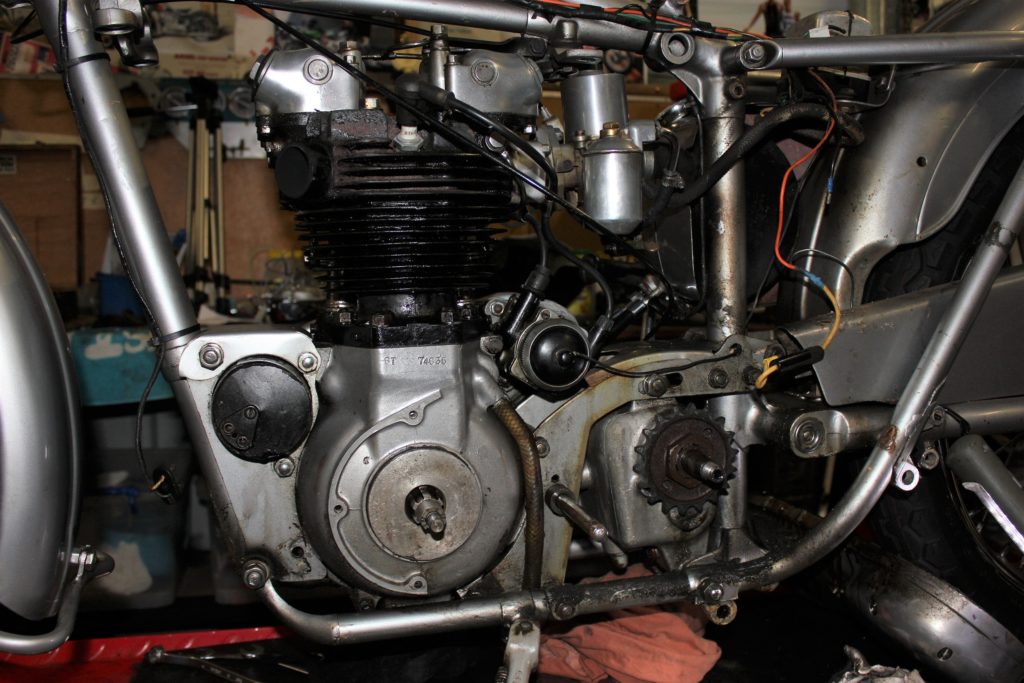

The 350 cc Norton single.

You’ll recall the story of the Triton, a parts bin special created by throwing a Triumph twin engine in a Norton frame? The featherbed frame, which is discussed at length in the Triton story, was a huge success for Norton. The twin down-tube, cradle style frame was to become the signature to the Norton motorcycle racing effort. They had long proven they had the best engines, the featherbed frames simply helped the company assert their racing credibilities and maintain their dominance in the two-wheeled, racing world (I’m sure that’s poke a hornet’s nest so hit me with your best shot :).

Elsewhere in the range, the single down-tube frames were left for commuters, tourers and those wishing to fit sidecars – which were a big thing in Britain as the country recovered post-war. The Buz Norton is of the second group, not a risk of losing it’s engine older, single down-tube, ‘pre-featherbed’ frame. I say this in parenthesis because they were never actually referred to as pre-featherbed,’ this is a retonym used by various people and groups, such as parts suppliers – some of whom I’ve become intimately acquainted with.

The fuel tank, single down-tube frame and engine before restoration. Note the sidecar lugs on the frame (visible near each end of the fuel tank).

Andover Norton has been the preferred parts supplier. They are very fast in getting gear out to Australia but as far as the singles go, parts are limited. I’ve also found the catalogue is not too accurate, which has resulted in me receiving an axle that doesn’t fit. “And where’s the original axle?” I hear out there on the ether. Being a basket case, which by definition is a jumble of bits and pieces, some things have inevitable gone missing. The rear axle being one such item.

One of the hazards of international purchases, they don’t always fit.

Speaking of axles, we have two freshly build wheels waiting to be fixed to the machine. They are brand-new, stainless rims and spokes laced to freshly vapour-blasted hubs. They look fabulous. Shiny, but not too so. The modern rims and spokes, together with the original, sturdy hubs have resulted in some tidy rolling stock. It will be a long time before these wheels wear out.

The new front wheel. It will be a long time before this one ever wears out.

Elsewhere on the bike, having done the math, it was economically and mechanically sound to dispense with all the broken and rusty clutch parts in favour of the beautifully crafted Bob Newby belt drive. These things are a work of art that would ordinarily over-capitalise such a machine as the M50 but there was simple nothing that could be salvaged from the original clutch so picking up a Newby belt drive and clutch set up has saved money, added reliability to the bike and lessens the likelihood of oil escaping the primary, because there’s simply none in there.

The Newby belt drive. A work of art that, sadly, won’t be seen.

The engine is snugged up, back in its rightful place. With vapour blasting shining all the alloy pieces and a lick of pain or plating on the metal components, the engine is looking as good, if not better than new. Plating consist of chrome or cadmium, the former costs a king’s ransom, the latter is not so bad. Like other forms of metallurgy, chrome plating, when done right, is of much higher quality than in the days when the Norton first travelled along the production line, which is what we’re aiming for with the whole bike.

Metalwork prior to cadmium plating.

Metalwork after cad plating.

Engine top end – before.

Engine top end – after.

Chrome-plated items.

The rear guard is back from the painters and is so shiny you could do your hair in the reflection.

by Dan Talbot | Oct 2, 2019 | Collection, Projects

I was recently having a chat on messenger with Mr Fritz Egli himself about Nortons, specifically the modern incarnation of the 961 Commando, such as that which lives in my shed. Suffice to say Fritz is not a fan of the new Norton however I enjoyed tapping into his knowledge base, even if he did insist on telling me how bad he thought the Norton was. Anyway, after I figured we had developed a comfortable rapport, I clumsily steered the conversation towards my “Egli” build. Without another word Fritz left the conversation.

Mr Egli is quoted in Philippe Guyony’s 2016 publication Vincent Motorcycles, The Untold Story since 1946, on the popularity of unauthorized copies of his famous motorcycle frame design, “The were more than six workshops manufacturing and selling unauthorized copies of my frames all over Europe as the genuine ‘Egli-Vincent.’ of course, at first I was upset, but soon I regarded it as a compliment to my design and then I moved on (2016, p.6).”

I’m prompted to rename my project, I’ve been thinking of the Triple T (Taylor, Talbot, Triumph). Comments and suggestions for a name are welcome at the bottom of the page.

In the interests of revision, and for those that are new to this project, Colin Taylor, who has built over 90 Egli-style frames, was tasked with building a frame for me to plonk a T150 Triumph 750 triple engine into. It is my intention to build a mid-seventies, part hot-rod, part superbike, special. An almost unique machine that will go as good as it looks. I say ‘almost unique’ because, as best as I can tell, there is only a handful other Triumph triples living in Egli-style frames that I know of. Indeed, Egli himself is rumoured to have built two frames for Slater Brothers in England to fit triple engines to and authorized the construction of another 12 by specialist frame builders in the UK at Slater’s direction. This was something I was about to discuss with Fritz when he terminated our conversation.

Tapping into online resources I’ve identified at least three Egli-style T150 motorcycles in France, one in Norway and the below pictured machine owned, crashed and burned by Marc Maslin in the UK. Marc’s motorcycle was one of the original Egli authorized copies and therefore comes with the blessing of Fritz himself. Sadly Marc’s bike underwent a Viking funeral (as Marc puts it) and is now resting peacefully in Valhalla.

Marc Maslin’s original Egli Trident T150v. The 850cc Triumph engine was fitted with a lightened and balanced crank, breathed through 30 mm carbs, had a gas-flowed and ported head, lightened and balanced pistons. Upgraded oil pump and enlarged oilways.

At the time of contracting Colin for the build I didn’t actually have a T150 engine but they are certainly easier to come across than the Vincent engine synonymous with the original design. I expected it would be a short time before I located a suitable engine, but, instead, I’ve been locating whole bikes, albeit barn-finds and basket cases. I now have a ‘71 BSA Rocket 3 and a ’74 Triumph T150, neither of which I’m willing to sacrifice to the build we are discussing here. Incidently, the causal relationship between the BSA and Triumph triple engine is a fascinating topic that can be read here.

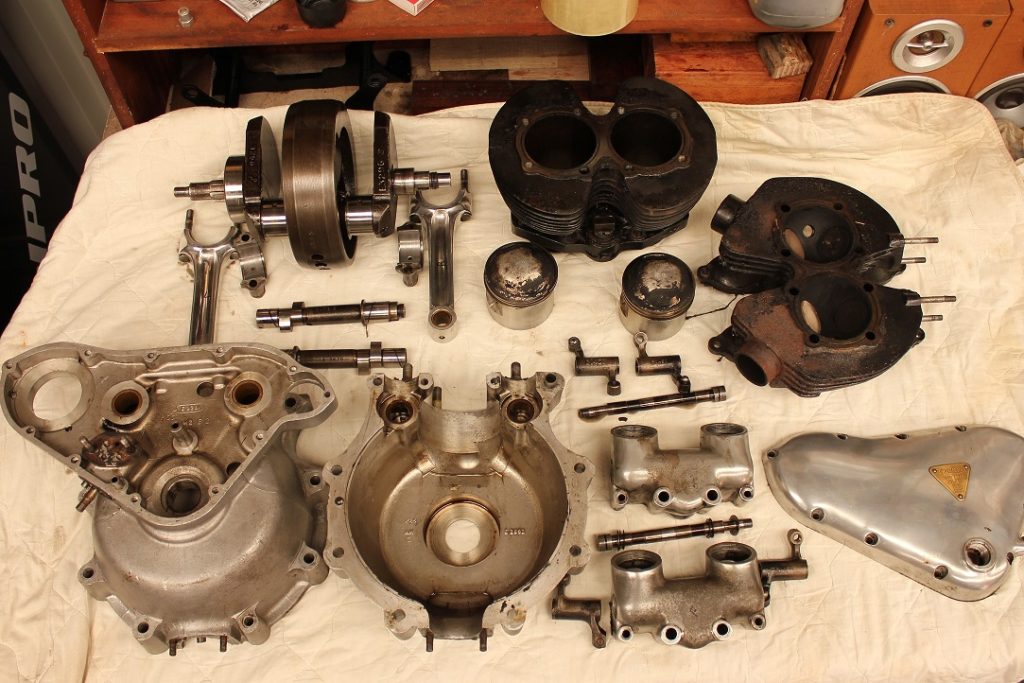

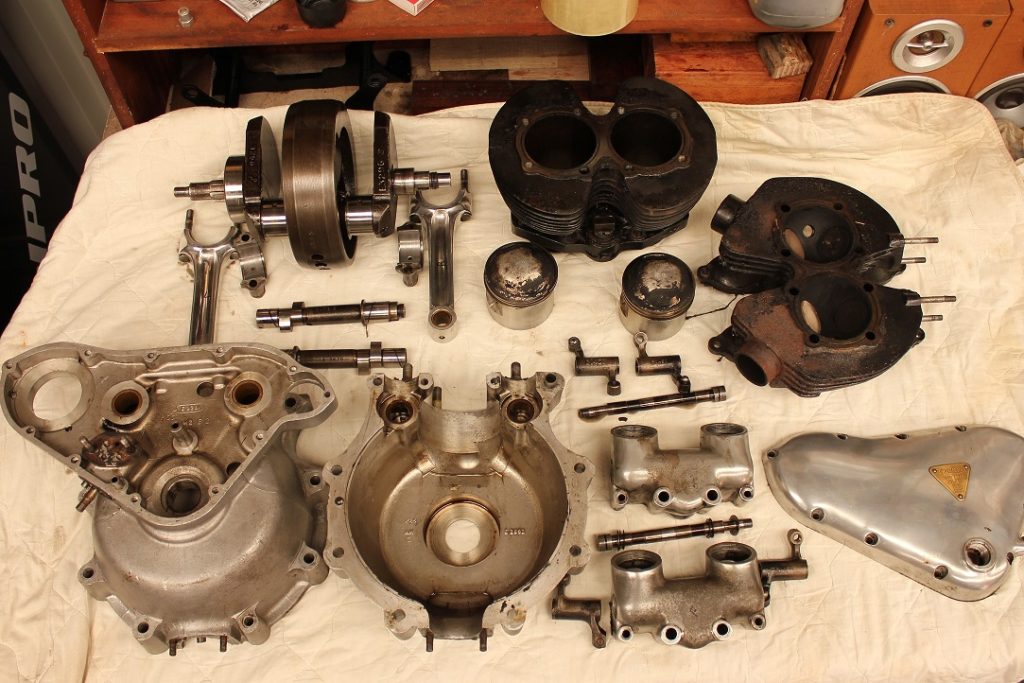

I also have an assortment of T150 engine cases, crankshafts, heads and other engine parts that I have brokered and bartered for over the past couple of years. To the casual observer it might look like I have enough bits to build three engines but most of it is quite poor quality and certainly won’t withstand the rigors of what I’m intending on building, however it does serve a purpose which will become apparent below.

Over the past few months I’ve been able to amass a few Triumph T150 engine cases and parts.

In August this year my wife and I returned to the UK and our favourite place in the world – the Isle of Man. In travelling to the Isle, we flew into Manchester and boarded a train for the one-hour ride to Liverpool. Sitting at the top of platform 5 in Liverpool, Lime Street Station, was Colin Taylor with my brand-new, nickel-plated, motorcycle frame. After many emails and me sending a not inconsiderable sum of money to Colin in the preceding months, we finally met face to face. I’ve read a lot about Colin and his creations and have seen his photograph numerous times in the motorcycle press so it was quite special meeting the man and being regaled by his jokes and general banter.

The author finally meets the specialist frame builder Colin Taylor – and takes delivery of the newly finished frame for our Triple T special.

I would love to say I was giving Colin my undivided attention but, in truth, I had one eye fixed upon my frame sitting on the floor of a very busy English Liverpool pub, dividing my time between that and chatting to Colin about all things motorcycling. We broke bread and drank Guinness and had a pretty good afternoon before Catherine and I made our way down to the ferry terminal and Colin headed off back to Nottingham (although he is an Englishman, Colin lives and builds his famous frames in Italy. I’ll leave Colin to add his contact details to the bottom of the page for anyone wanting to build a special).

I slung the frame over my shoulder and we set off on foot for the two-kilometre walk to the docks to board our ferry to the Isle. Along the way, a few curious onlookers, recognising a motorcycle frame, asked what machine it was intended for. If the frame sparks this much interest, imagine what the finished bike is going to do.

The frame is packed and ready for the long journey to Australia.

A week later, after an exhausting, 24 hour, non-stop journey from the Isle of Man to Busselton, Western Australia, we finally arrived home. I went straight out into the shed and tried my frame against one of the T150 bottom ends I have stashed there and, guess what, she fits.

So now I have my frame and my T150 donor bike, there’s one small problem. I can’t possibly separate the engine from this bike. This is a matching number, time-capsule from 1974, parting it out is not an option. Phil Irving, the Australian engineer responsible for designing the Vincent V-twin engine, in his 1992 Autobiography wrote, “there were those (including myself) who considered that every new Egli meant one less Vincent (1992, p.514).” I have no doubt many fans of the Triumph T150 would feel the same way. Sure I’ll take the odd part from the T150 but, when this project is done and dusted, that T150 will be the next machine to undergo a full restoration, to be brought back to its former glory. In the meantime: does anyone have a spare T150 engine they don’t need?

Up until now, this bike has been referred to as a ‘donor,’ insofar as the engine was intended as a base for the project. Having now secured the bike and moved it to our shed, this matching number survivor machine is too good to part out for a special and will eventually be returned to the road in original trim.

Despite the rust and dust, this motorcycle has had very little use. It was last registered in Ohio in 1981 and represents a true ‘barn-find.’

by Dan Talbot | Oct 1, 2019 | Collection, Projects

It should come as no surprise to anyone who knows me that throughout my life I’ve had a strong yearning to own a Vincent motorcycle. I’ve come spectacularly close to owning a Vincent about two and a half times but life had other ideas for me (and that’s fine). Vincents have, by and large, remained a figment of desire, the unicorn that was never going show up in my shed. Until now.

A Vincent motorcycle is the classical embodiment of speed and sophistication, a triumph of technical expertise from the golden era of the British motorcycle industry. For decades I have been immersing myself in the literature, both technical and folklore, around these motorcycles. Often I found the dream very nearly outgrew the reality, but dreams often do.

It has long been held Vincent motorcycles were advanced beyond their nineteen forties design but they were created by man, made of metal and alloy and they’re not exactly rare, just very expensive, so, fiscal resources aside, my dream was destined to one day become a reality – I just didn’t expect it would take me forty years! Of course, having been created by man so too can they be improved by man. One man particularly versed in improving the Vincent is Terry Prince.

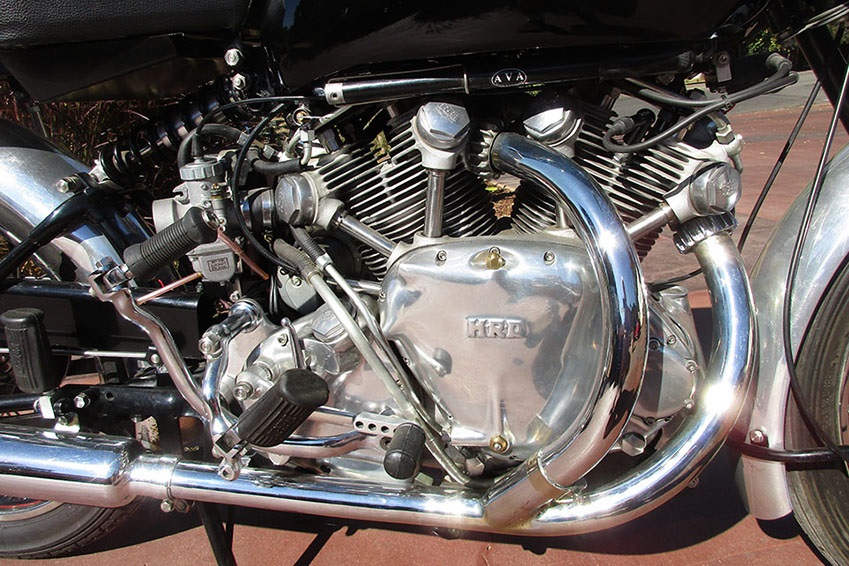

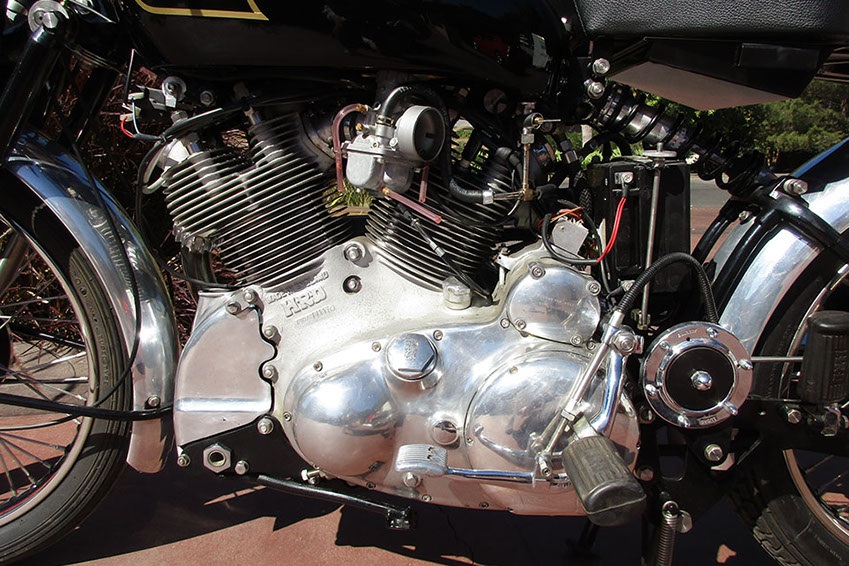

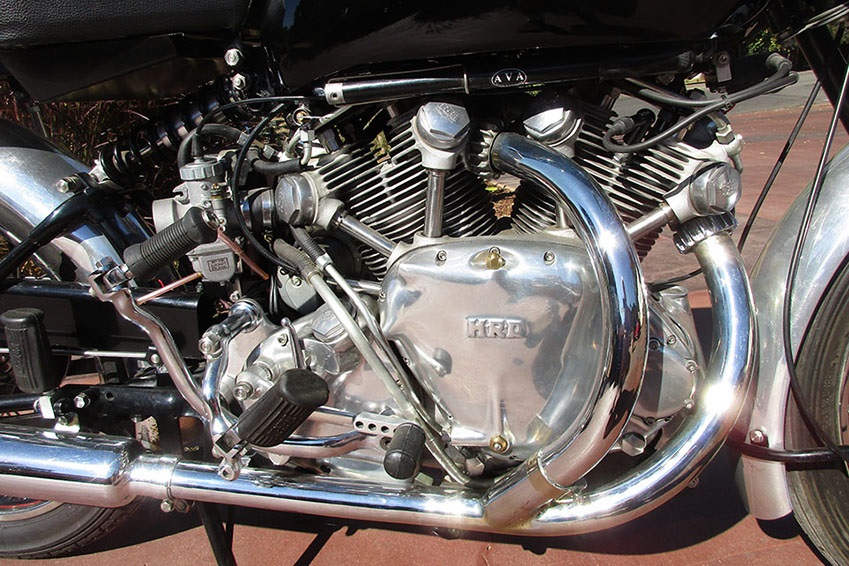

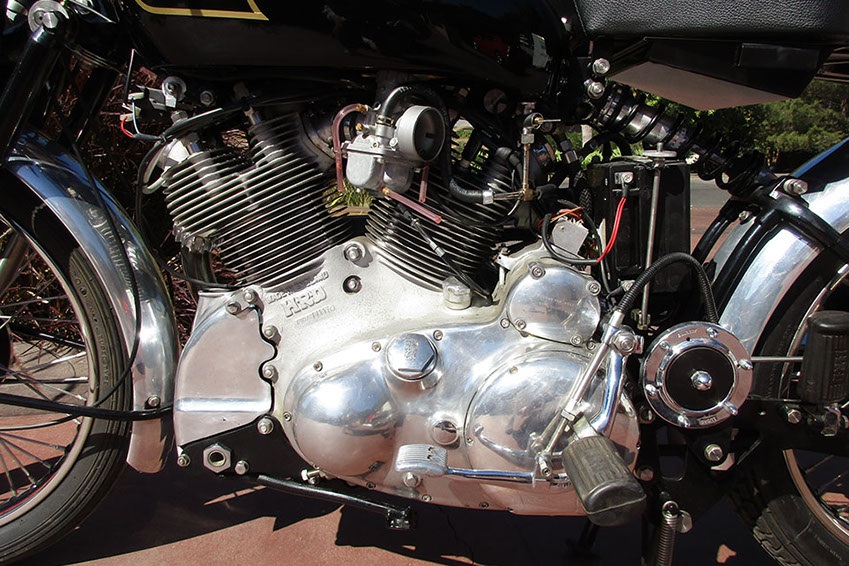

At the heart of the Vincent, indeed the great majority of the bike, is the stonking, huge v-twin engine. One of the most iconic images in in all of motorcycledom.

Throughout the life of the Vincent motorcycle a few names come to the fore, Howard Raymond Davies (HRD), Phillip Vincent, Phillip Irving and Terry Prince. There’s a great many others but those four gentlemen feature prominently in Vincent discourse that I’ve been drawn to over a lifetime of consuming information on the marque. With Terry Prince being the only who is still alive, and therefore still active in Vincent engineering, he is keeper of the Vincent flame. Terry is known around the world as one who will manufacture a complete, Vincent engine, and even the whole motorcycle, using modern engineering and materials.

Terry Prince (far left), has a life-long association with the Vincent marque and is recognized today as one of the most knowledgeable people in the world as an expert of these unique machines. Terry is photographed here at Bonneville Speedway where his 60 year-old motorcycle set a world land speed record in 2010 – with Terry at the controls! Photograph courtesy Terry Prince.

When a 1948 Vincent Rapide popped up on the market laying claim to having been restored by Terry Prince consisting 85% of new parts it well and truly pinged my motorcycle radar. Here was a Vincent that promised a balance between original, precious metal and a road-going, reliable link to the iconic motorcycle. The advertising blurb read, amongst other things, “Prince’s hand is evident all around the bike, starting with the front brake hubs, which contain four-leading-shoe internals. Suspension has been upgraded with modern dampers front and rear. An accessory tread-Down centre-stand eases parking chores. The Shadow 5in. ‘clock’ perched atop the forks is a nice touch. Of course the engine – just overhauled by Prince and breathing though modern carbs.”

The Black Shadow, 150 miles per hour, speedo is a nice touch to my Rapide. Indeed, many Rapides are upgraded with the massive 5 inch instrument.

The 5 inch clock is a massive speedo that has been lifted from Vincent’s own hot-rod, the Black Shadow. Rumour has it people have been booked for speeding by police who have been able the read the speedo from a position slightly astern of an errant Vincent rider. There were some other Shadow touches that added to the desirability of the machine, although, it should be said, a Vincent Rapide in stock trim is a highly desirable machine on its own.

I resolved to call Terry Prince.

Having made the decision to call Terry, I found I was a bit nervous. What if I wasn’t deemed competent to own a Vincent? I had let opportunities of ownership slip through my fingers in the past, maybe the motorcycle gods had already decided I wasn’t eligible to join the ranks of Vincent owners. Or, perhaps it could be fatalism with all the other machines being pushed aside until this one came along. With all the nervousness of a job interview I made the call.

Dave “Bones” McLauchlan racing Terry Prince’s Vincent solo bike. The engine in this machine is producing more than three times the power of its original output! Photograph courtesy Terry Prince.

Within moments of calling Terry Prince I was relaxed and we were chatting like old friends. The more we talked the more I wanted that motorcycle. I learned the bike had been reassembled by Terry from a basket case presented to him along with a Vincent Black Shadow. At the time of building the machine it was Terry’s intention keep it as his personal everyday rider, which reinforced the notion of no expense spared when it came to building the machine with upgraded brakes, suspension, modern carbs and electronic ignition.

At the time of calling Terry two other people had expressed an interest in the bike and one was particularly serious, so serious in fact the bike had been shipped from the US to Melbourne as the prospective purchaser lived in Victoria. How the bike came to be in the US is a long story, but, at the time of my call, it was still sitting in California.

Before the bike was due to leave the US a Black Shadow came up for auction in Australia and purchaser number one was keen to bid on it and Terry was prepared to hold the Rapide pending the outcome of the auction. Evidently he won the auction, with a bid of $AUD160,000, as two days later when I phoned Terry he hadn’t heard from either gentleman and the way was cleared for me to send my deposit to secure the motorcycle. I hurriedly sent off a great chunk of the funds I had set aside for my daughter’s forthcoming wedding (sorry Love).

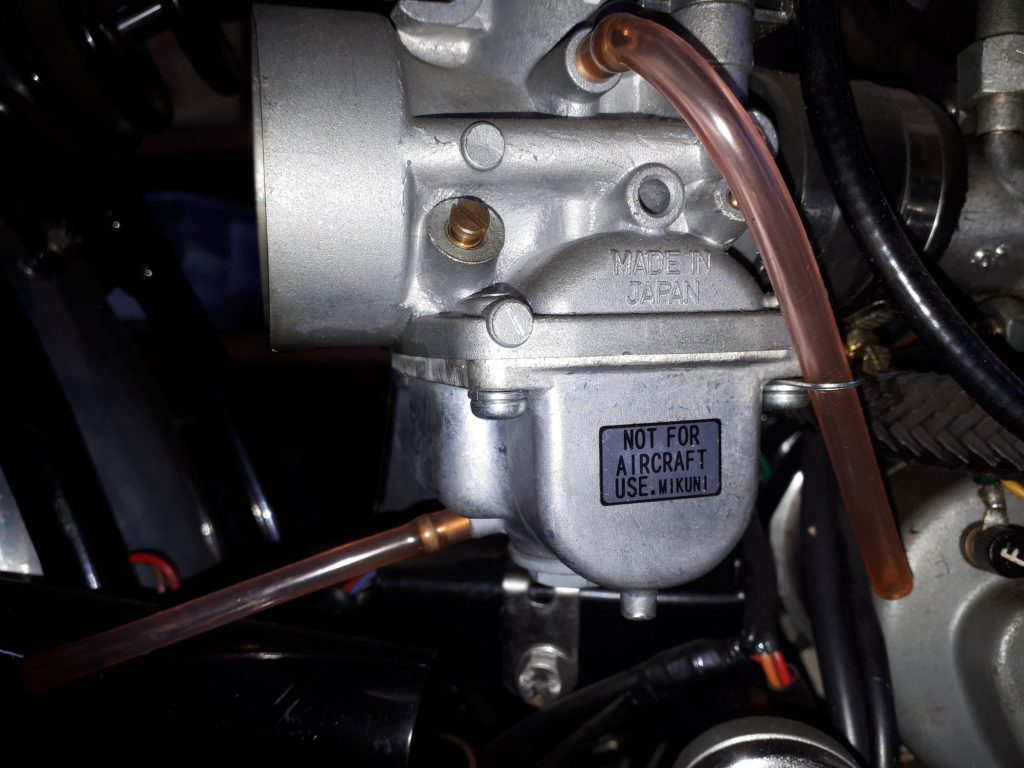

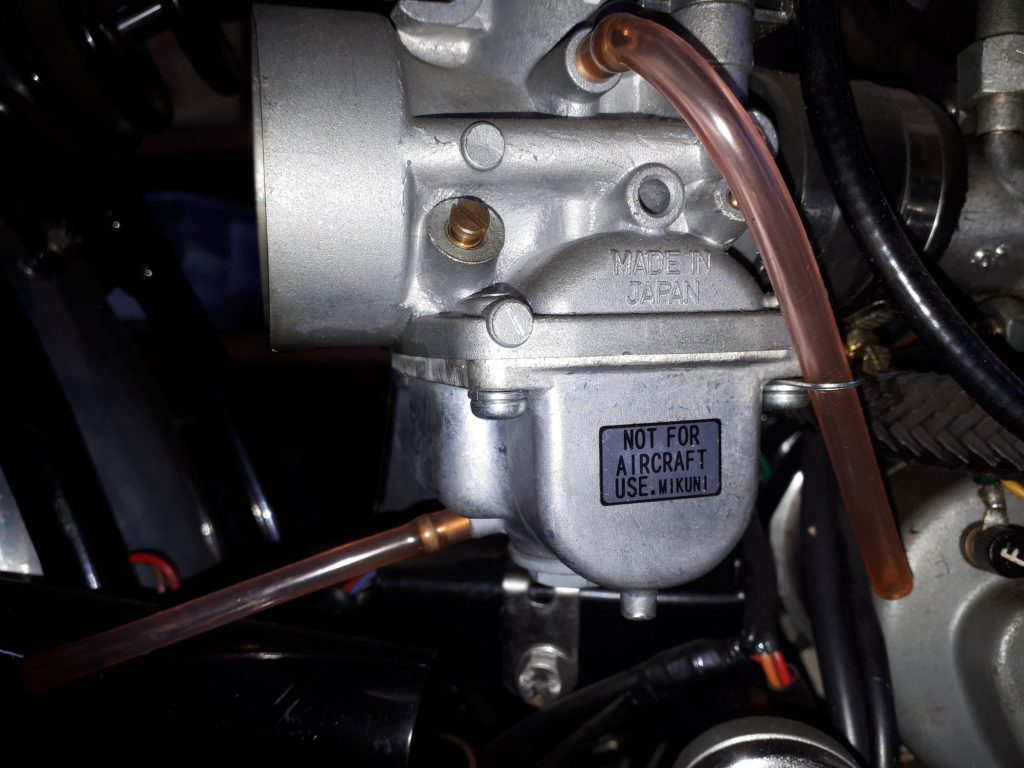

“Not for aircraft use,” probably not for Vincent use either in my book. Mikuni carburettors work well on Vincents, and in my Triton, but having desired a Vincent for over 40 years and pouring over countless machines, photographs and references of these fascinating motorcycles, everytime I look at my Vincent, my eye falls to the Japanese carbs. They will probably be replaced with original Amal items in the very near future.

Sometime later the Vincent was loaded on a ship destined for Melbourne. I waited a few short weeks and as soon as the boat berthed in Melbourne I booked my flights, first to Melbourne to check out the bike and secondly to Sydney to meet the man himself and hand a cheque over.

10 weeks after striking our deal I was standing in front of my Vincent (I still get a pang of excitement when I say ‘my Vincent). She’s a beauty. After two years in the US she’d lost a bit of lustre but I know within a few hours of the bike arriving in my shed she will be looking as good as new. I spent a couple of hours running my eyes and hands over the bike and heard her running. Satisfied with my purchase I set off for Sydney.

A 40-year dream of owning a Vincent motorcycle is a reality.

Arriving at Terry’s forest hideaway I’m met first by Ursala and then Terry comes out to greet me. Again, I’m immediately at ease with this couple who have invited me into their house for the night. After coffee and a chat I was treated to a visit to the workshop. There was four Vincent motorcycles and an at least one complete engine in the workshop. I was particularly intrigued by the engine because it is a new one, made from all new parts. Sadly, the parts don’t simply just bolt together and, out of frustration, it has been sent to Terry to rectify and make usable, causing him a host of frustrations. Had he been on the job from the get-go it would be fine but now Terry is having to go back to bring someone else’s work up to spec. It’s a difficult and costly task which, at the end of the day, will result in someone having spent a lot of money for a replica Vincent engine.

Standing in the workshop, I’m juxtaposed between the old and the new, where items from this century and last are found in the same engine. Terry’s original engine, one he’s owned for close to 65 years, sits in a modern chassis and is reportedly pumping out over three times its original 45 horsepower. That same engine has also seen regular service in Terry’s Land Speed Sidecar – which still holds world records at Bonneville Speedway. This creation is not unlike Bert Munro’s famous Indian, except Terry started with better stock in the Vincent than a clunky, old vintage Indian.

The stock of new parts, heads, barrels, pistons and just about everything that has a thread is tantalising. One of my close calls to Vincent ownership includes me recently bidding on a pair of Vincent crankcases. Two lumps of alloy that were sold for close to $AUD5,000. At the close of the auction I was slightly relieved not to have been the winning bidder, a relief that was even more palpable when I saw the look on Terry’s face as I recounted the story. Suffice to say I would have been up for a lot of money to bring those crankcases up to anything resembling a functional engine.

Anyway, I needn’t worry about that now as I have the genuine article complemented by some modern parts that maintain the authenticity of a 1948 motorcycle in a package that will outlive me, even if I ride it every day for the rest of my life – which is exactly what I plan on doing.

by Dan Talbot | Jul 7, 2019 | Collection, Projects

“Here was an utterly beautiful engine, lithe, angular and a metallic onomatopoeia for power (Frank Melling, Motorcycle USA).”

Written 82 years ago, when onomatopoeia was a still a thing, Mr Frank Melling had just sampled Triumph’s 500 cc Speed Twin and was clearly impressed with his test ride. Frank was actually saying the Triumph engine sounds as good as it looks and who could argue? The Speed Twin was by any measure a huge success and introduced an engine to the world that would take the company into the eighties.

Such is the success of the modern Triumphs, one could be forgiven for thinking the Thunderbird is a relatively recent addition to the line-up. In truth, the Thunderbird was released in 1949 and gained instant notoriety as a genuine 90 mph superbike and the machine of choice for bad boys around the world, due in no small part to the character portrayed by Marlon Brando in the movie The Wild One. We’ve previously discussed the history of the Thunderbird on the Motor Shed and it can be revisited here. This piece is about the restoration work our Thunderbird has enjoyed since coming into our possession over 20 years ago.

During most of that 20 years I had been looking at my 1956 Triumph Thunderbird thinking, “I’m not happy with the grey frame.” The bike looked pristine when we acquired it but after many years of use and abuse the lustre began to wear off and she became in need of a spruce up, giving me the ideal excuse to pull the bike down and do some colour changing, amongst other things, more important things as it would turn out.

- The all-silver livery of our ’56 Triumph Thunderbird never really grabbed me. What I really wanted was a Blackbird, or so I thought.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, the Thunderbird engine actually needed to be completely pulled apart. With the greatest respect to the person who rebuilt the bike before we acquired it, there’s a critical piece deep within the engine that has a finite operational life and it needs to be replaced with some regularity but is often over-looked. The plan was to pull the engine out, paint, plate and polish every surface and return the Thunderbird to the road as a new machine.

I had a particular fondness for the rare, all black Thunderbird which was sent to America following the popularity generated by Brando’s gleaming black 1950 machine – in a black and white movie of all things! Long before Honda came out with their four cylinder, plastic-enclosed behemoth, the all black 650cc Thunderbird was dubbed the ‘Blackbird.’ And it’s a stunning machine. Rich, black paint contrasts well with polished alloy and, as is the case with classic machines, highlights the era perfectly. Yep, my ’56 was going black.

- Stunning in black and polished alloy this limited release Thunderbird was dubbed the Blackbird. Photograph provided by Thomas Duffy, the owner of this beautiful machine.

In the weeks and months leading up to me beginning the restoration, trawling through the internet of things I stumbled upon a rare colour combination of silver on black. The bike had been restored by Choppahead Kustom Cycles in Massachusetts and it is the perfect embodiment of the classic Triumph that has been with us since Edward Turner unleashed his famous Speed Twin on a world seeking beauty and performance in a motorcycle. I could no longer look at my all-over silver Triumph in the same way and even the hitherto lusted-over Blackbird became merely a crow. I had moved through the various mental stages of change (you know; procrastination, contemplation) and now it was time for action.

- This ’56 Thunderbird was restored by Choppahead Kustom Cycles of Freetown, Massachusetts. Once I laid my eyes on this bike thoughts of a Blackbird were lost to the ether of my mind. Special thanks to Choppahead for allowing me to use this photograph.

Twenty-something years of use had left its mark in the form of paint chips, faded chrome and rust starting to show through here and there. I was further able to justify the pull-down by claiming the oil leaks needed to be fixed (I’m serious), the magneto needed attention and the cleanliness, or otherwise, of the infamous sludge-trap, was an unknown. Now, I’m the first to agree the term ‘sludge-trap’ has a fictional tone but it is a real thing and ignoring it can destroy a classic Triumph engine, it is the critical piece I mentioned above. In the days before oil filters, some manufactures, in the interest of engine longevity, put a screen filter inside the crankshaft oil circuit. So, let’s have a little think about that – the oil filter is inside the crankshaft. Anyone with a modicum of knowledge around the construction of the internal combustion engine will recognise the inherent problem around this design.

When we first purchased the Thunderbird it looked brand new. Attention to detail was amazing and it ran really well but there was a couple of tell-tale signs of trouble brewing deep inside. Clearly the magneto hadn’t been touched. Once the bike heated up it was extremely difficult to start which is a sign the maggy is on its way out. In a world governed by constants, temperature coefficient of resistance left me having to give the warmed-up 650 an extra, extra hard kick to overcome the resistance of the hot maggy coils in the hope I could generate a spark strong enough to start the engine. Once started, the ancient twin would squirt oil everywhere, including all over my jeans and boots. Oil would shoot out of places hitherto unknown to contain oil or require lubrication. Seriously, oil would somehow hit the bottom of the fuel tank then run of the seams making it look like the tank had its own secret oil reservoir. A degrease and polish would have the bike looking a million bucks but that would only last as long as a decent ride.

So there you have it, sludge-trap, magneto, oil leaks and beautification were my motivation. The Thunderbird was pushed onto the hoist, anaesthetic was administered and she went under for some major surgery. It’s not as if I had nothing to do. My Mustang rebuild was languishing away quietly in the corner of the shed, my Triton, like an insecure toddler, was in constant need of attention but, by crikey, that Thunderbird was coming apart.

The bike came apart reasonably easily. It was grubby behind all the surfaces that I couldn’t reach with my very thorough detailing but built up oil and grease does wonders for preserving the metal on which it cohabitates. When it came time to turn my attention to the engine, that too came apart really well. There are some specialist tools required and I purchased some and borrowed others. Eventually, I had the engine, in fact the whole bike, down to irreducible parts, in other words, every last nut and bolt had been removed.

The venerable Triumph parallel twin has been with us for over 80 years since it was introduced to the world as the 500 cc Speed Twin. In 1949 the engine grew to 650 cc in the Thunderbird. Note the SU carburettor. In the mid-fifties Triumph experimented with these carbs and they proved successful but were possibly too expensive to continue with.

- The 650 cc engine.

I was more than happy to learn the big-end bearings were marked as “std” which indicated the crank had never been ground. Bonus. The bearings were also stamped with 08JU90 so I could safely say the engine had been rebuilt sometime between 1990 and 1993. Recall from part I, we bought this bike after it had been restored, sold to an intermediary, sent to the UK where it sat in a container for two years before being returned to WA.

The pistons were .20 over which indicates in 62 years the bike had only undergone one rebore. I began to think ‘maybe new pistons, rings and bearing would be enough.’ And maybe not. Here I was contemplating ignoring one of the primary reasons I pulled the engine apart, mainly because I was out of my depth. The crank would need to be handed over to the experts to expunge the sludge, of which, there was plenty. Like the tailings from of some black gold mine, the substance had a hint of a sparkle from decades of engine grinds mixing with mud and other impurities. Just as well we looked.

- The sludge removed from deep within the crankshaft of my Thunderbird had a hint of a sparkle from decades of engine grinds mixing with mud and other impurities.

- The engine is out of the bike and about to be pulled apart. Note the ever-present camera which will record the proceedings with about 500 photographs, a practise that has proven invaluable over the years.

- Back in the nineties the Thunderbird was a bit of a farm-hack on our family property.

- 20 years later, same motorcycle, same kids.

by Dan Talbot | Jun 22, 2019 | Collection, Projects

With the Mustang body well on its way to being straight and true, it was time for me to turn my attention to the heart of the beast, a 289 cubic inch Windsor V8. The Windsor story is a fascinating one so grab a cup of tea and we’ll talk a tale of two cities.

In 1904, in what could be the first ever case of badge-engineering, Ford opened a manufacturing plant in Windsor, Canada – across the river from the US Detroit parent company. The idea was to assist the company to gain a foothold into Canada and elsewhere in the British Empire.

Evidently the experiment was successful. The plant later incorporated an engine casting facility and, in 1962, introduced the Windsor V8 engine to an automotive world hungry for power and speed. The modern, new Windsor engine was a marked departure from the previous design and it was an instant hit.

In this ‘everything old is new again’ world, the old Y block V8 is enjoying somewhat of a renaissance amongst hard-core enthusiasts but I’m sure, back in the day, they were quickly shoved aside in favour of the sportier new-comer.

Such was the success of the Windsor V8, production extended long after its replacement when the Cleveland was introduced. In fact, the Windsor was used for another 18 years beyond the short, 13 year span of the Cleveland that ceased production in 1982. The Cleveland engine, as the name suggests, was produced in Cleveland, Ohio. It was intended to be a more robust and versatile engine than its predecessor. The Cleveland lived up to expectations and proved very successful in racing, particularly in Australia where it was a game-changer in the Falcon GT. The Falcon GT was a dream-car to many a teenager growing up in Australia, including me. The advent of the Cleveland, for us kids, signalled the end of the Windsor. Everyone knew, if you wanted to be in the race a Cleveland was the only way to go, notwithstanding both engines came in 351 cubic inch displacement. Like the Y block before them, Windsors were shunted aside and ended up in cars driven by the slightly more wealthy members of my cohort.

But then a strange thing happened, the Windsor refused to leave the stage.

Having pinned their future muscle-car ambitions on the Cleveland, Ford planned to phase out the Windsor in the late seventies, but the perennial heart-beat from across the river had other ideas and Detroit were forced to keep sending it out into the world. It stayed on in 302 cubic inch format up until 1982 when it was re-badged the 5.0 (litre) and remained in production up until 2000 when the last of the fuel injected, roller cam engines were put out to pasture. It was one of those, the last incarnation of the Ford Windsor V8, that I had my eye on for the Mustang.

The tired, duty, oil-leaky 289 Windsor V8 had to go. Note the dedicated gas set-up the previous owner had installed (no doubt at great expense).

My car was from the sixties and it was produced with a Windsor V8 which meant this was the only option. A bonus here is the direct connection to the seventies when those afore-mentioned, financially capable friends of mine were running around garnering my envy in their Windsor-powered cars. Four decades later, I’m set to revisit those days, the days before the fuel injected, refined, perfectly timed and smooth V8s we’ve become accustom to.

Out with the old.

To be fair, there’s no shortage of roller-cam V8 engines looking for cars to inhabit with a lot of people being put off by all the fuel injection hardware that sits atop the engine, they are a natural turn-off. Fuel injecting a Windsor is the automotive equivalent breast augmentation, it looks great but it comes with high maintenance and takes skills far beyond my fumbling fingers to master so losing the fuel injection unit was a must. When I lift the bonnet on my 66 Mustang I want to see a bright blue Ford Windsor V8 at home in there with a 4-barrel Holley breathing through a classic Ford air-filter.

I had read on the internet it was quite a simple task to throw out the fuel injection and return the engine to the less socially acceptable form of fuel delivery from the last century – the carburettor. To achieve this I would mainly need two things, an engine and a carburettor. As it turned out, I would need many things but these two items seemed like a good start (the 289 engine I removed from the car had been gas-powered so there was no carburettor with that).

The 5.0 roller cam Windsor I settled on was a used American imported item falsely described as ‘refurbished.’ I would later learn refurbished is semantics for paint and gaskets, which probably explains why the engine was so cheap, however, there was a bonus: I could take my pick from a nearby pile of carbies. In a nod to the environment, I selected a 480 cfm unit. Sure, it’s got four barrels but it’s in the smaller range of the 4-barrel Holley family and at the end of the day, my car is intended to be a cruiser anyway.

The last hurrah for the Windsor V8 engine. This fuel injected engine was reportedly ‘refurbished.’ In truth, it had a few gaskets replaced. Note all the fuel injection hardware at the top of the engine that had to be removed.

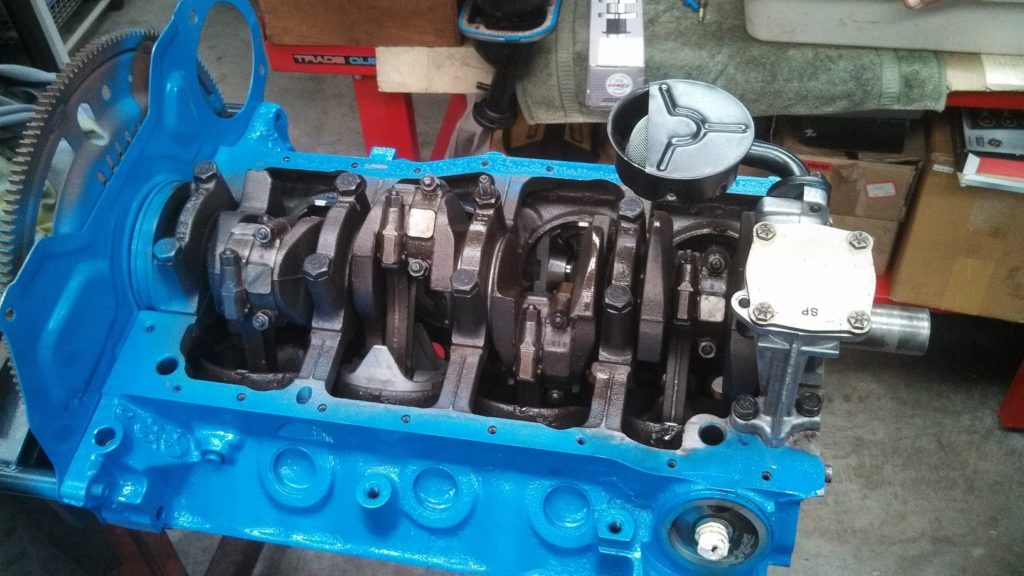

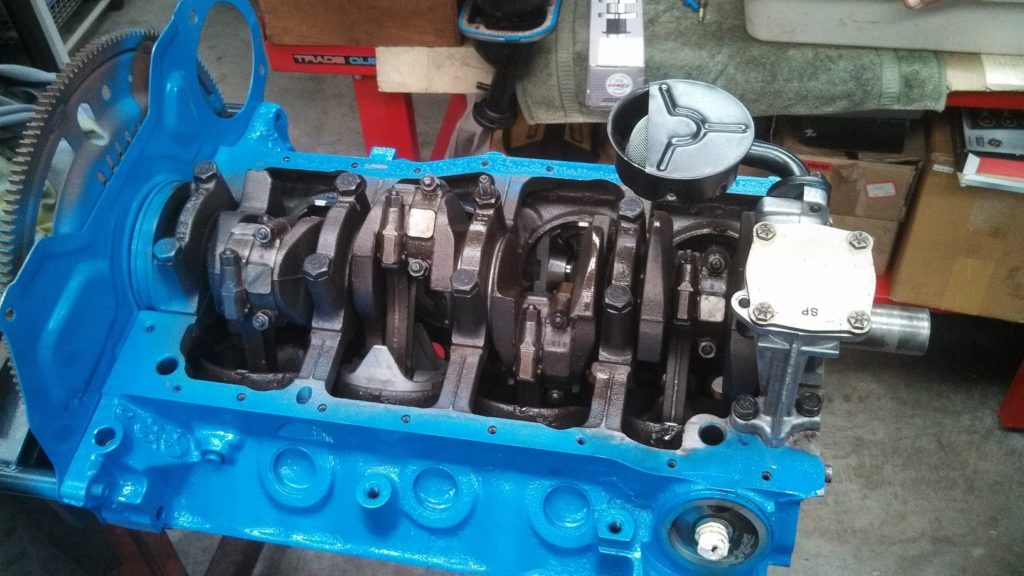

Feeling pretty chuffed with myself, I took the engine and went off to get a Windsor expert to run his eye over it and help return the unit to carburettor fed. Having been with us since 1962, these things are quite rudimentary but, as it turns out, there was a fair bit more required to return a carburettor to the Windsor than I had anticipated. The list included a new inlet manifold, camshaft, distributor, coil, water pump and fuel pump. I wanted someone I could trust to turn me out a good engine at a reasonable price and, to that end, I chose Paul Poller of SpanaWorx Mechanical Services. Paul’s easy-going nature and sensible approach to engine builds was ideally suiting to adapting the 302 for service in my ’66 Mustang.

My bargain engine basically needed a full rebuild. Here, Paul is treating it to a new oil pump – adding to my peace of mind.

There was a prosperous time about 10 years ago when the Australian dollar was on parity with the US greenback and we enjoyed the bountiful US performance market with relatively little trauma to the hip-pocket. Importing used engines from the US was a thing and some of the more creative exporters turned, shall we say Dickensian, in using elaborate terms to sell scrap metal. I accept I jumped into the unknown but I wasn’t expecting someone to have drained the pool.

In she goes. Well almost. The sump got hung up on the cross member and the engine would not seat properly. A simple fix was to swap it with the sump from the 289.

By the time I took delivery of my sparkling blue Windsor V8 it had new rings, bearings, camshaft, alloy heads and host of external parts to add beauty and practicality. The old 289 was no slouch but I’m expecting my new, improved heads and lumpy camshaft will add a few horsepower to the already spritely 302.

Getting close now and relying on Google for some last minute tune-up tips.

My carby was sent off to Xtreme Fuel Systems in NSW where it was transformed to better than new. This is the third carby Xtreme have reconditioned for me and I highly recommend them. I took the carb out of the box and simply bolted it onto the engine. The carb is yet to be dialled in, but the engine burst into life after a few short bursts on the starter motor with a deep rumble that has been absent from my life for too long. It is immensely satisfying to hear that car running again.

Hear it here; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rrb51yf_2W0

The rebuilt Holley carb is a thing of beauty. Xtreme Carburettor Rebuilding in Cambelltown, NSW are highly recommended.

When I lift the bonnet on my 66 Ford Mustang I want to see a clean and tidy Windsor V8 engine breathing through a classic Ford air-cleaner – in this case a Shelby replica.