by Dan Talbot | Feb 19, 2024 | Collection, Projects

Rocket 3 Rebuild, Part IV. She’s done!

By Dan Talbot

The legacy of the BSA Rocket 3 lives on among motorcycle enthusiasts, as it was one of the early examples of a high-performance British motorcycle with a distinctive design and powerful engine configuration. Today, vintage BSA Rocket 3 motorcycles are prized among motorcycle enthusiasts and collectors.

Cast your mind back to 1971. I was in primary school, hooked on dirt bikes and pouring over Dad’s Cycle World magazines (except when I found his stash of Playboy mags). I recall peeling through the pages mainly for dirt bike stories but, if I remember correctly, road machines figured most prominently in Cycle World and the British verse Japanese debate was raging. The Honda 750 and Kawasaki 900 were emerging as unbreakable spaceships compared to the aging British machines, such as Triumphs, Nortons and BSA.

I had leaning towards BSA because at that time my most prized possession was a BSA .177 calibre air rifle. As attractive as the BSA bike and the fashion models draped across it were, I was a little vexed because I felt the Triumph Bonneville was a superior motorcycle. This assessment was based solely on my unscientific observation that the coolest dudes rode Bonnevilles.

Five decades have passed since those days and I have owned no fewer than ten Triumphs, including two Bonnevilles. Aside from my air rifle, I have owned only one BSA and right now it’s taking pride of place in my shed. Purchased in August 2018, it’s been a very long journey to getting the motorcycle back to better than new condition. I know that sounds like a big call but I will make my case below, but first I must backtrack a little.

the Rocket was introduced to readers of the Motor Shed in 2019, with Part II published in March 2021 and, more recently, Part III hit the site in March 2022.

A basket case in the truest sense. This is what we started with!

The restoration has been a five-year journey of industry and hiatus. The industrial component played out in a nexus of time, money and inclination, hiatus occurred when one or more of these positions was challenged or lost. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say this has been an epic job – check out the ‘before’ photograph.

The bike was a basket case in the truest sense of the description. I was, at the time, looking for something a little more substantial but as soon as I saw the BSA, I recognised it as a Rocket 3. Importantly, it was one of the latter, American export versions – there are various names used to describe the Mark 2 Rocket, laziness has me resorting to the ‘export’ designation. To my mind, the exports were the more handsome, if not slightly impractical, version of the Rocket. The tiny petrol tank has limited range, there’s so much chrome bouncing back at you riding on a sun-shiny day can be hazardous and the handlebars may hint at Easyrider but when you’re 6’ 3” tall, they more hinderance than help. I have resorted to UK-style Bonneville bars, the likes of which were on my first ever road-bike – a ’76 Bonny.

At the time of spotting the Rocket, I was in search of a Trident engine. Certainly, there were Tridents in the same shed, some of which were for sale, but my resources would only stretch to one project and I seized upon the Rocket for a very reasonable amount. As it would transpire, seized is a good choice of word. The engine had purportedly been rebuilt in the USA. The certificate of title, issued by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, recorded the milage in June 1975 at 4161. The speedo that came with my bike had 5274 miles on it so one wonders what caused the need for a rebuild. As it turned out, the ‘rebuild’ was more of a rebore, and the pistons had been parked up in the bore for so long, the rings were rusted to the bore. In other words, the rebuild had set me back because the engine was in need of new liners. That was 2018.

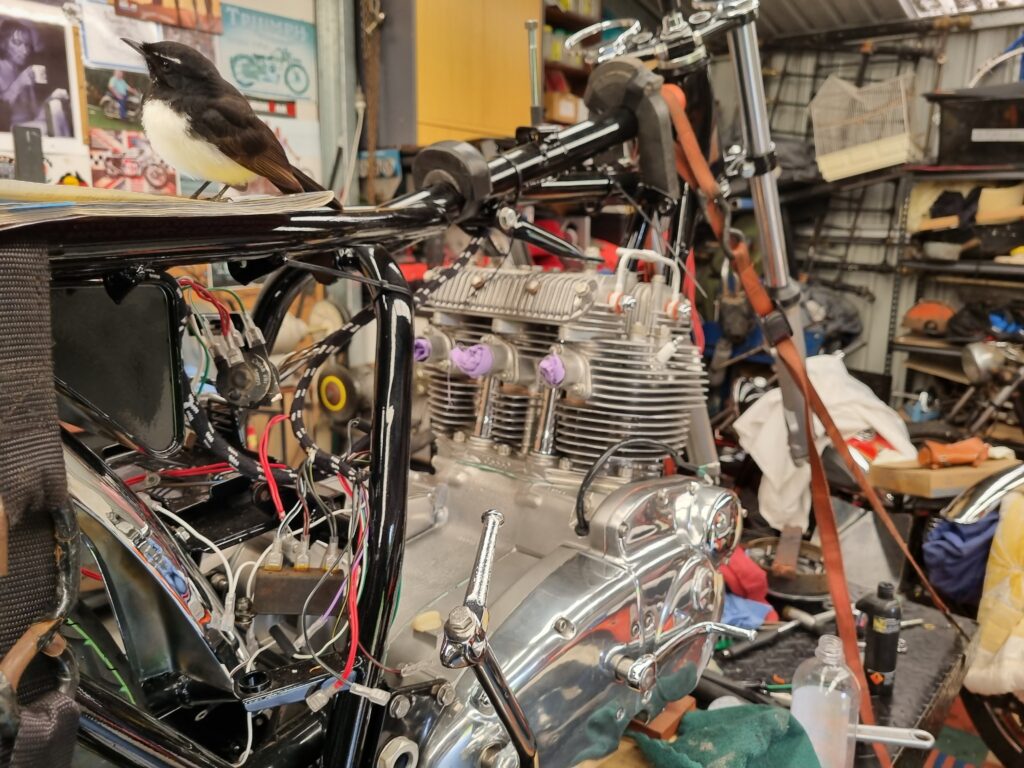

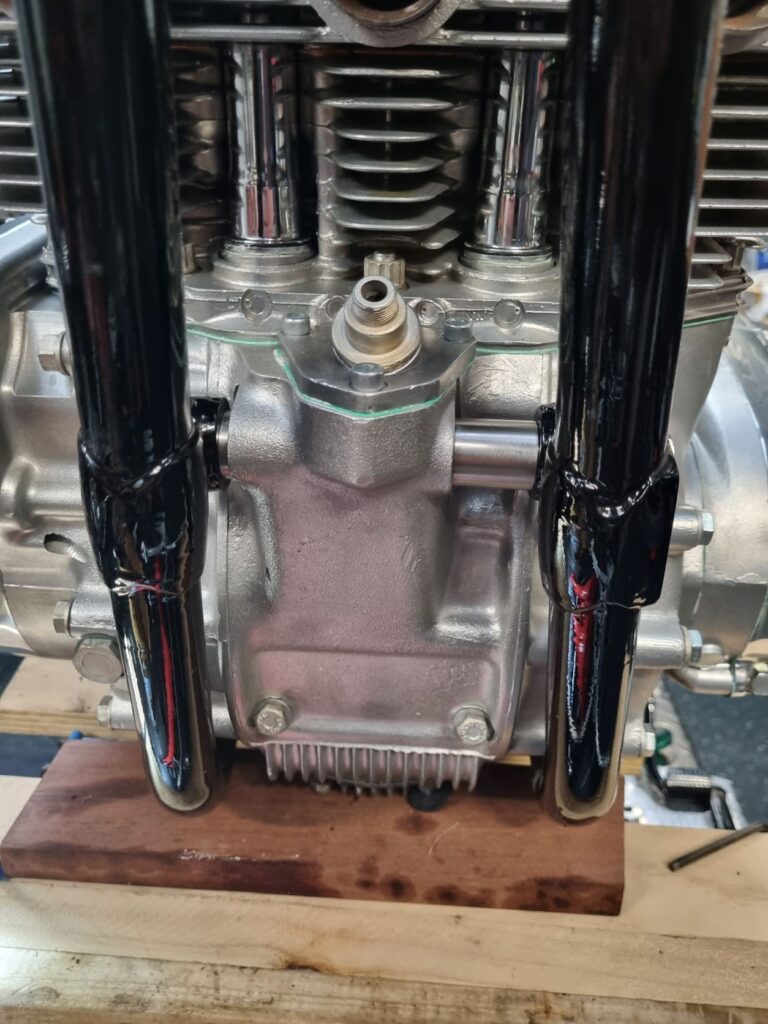

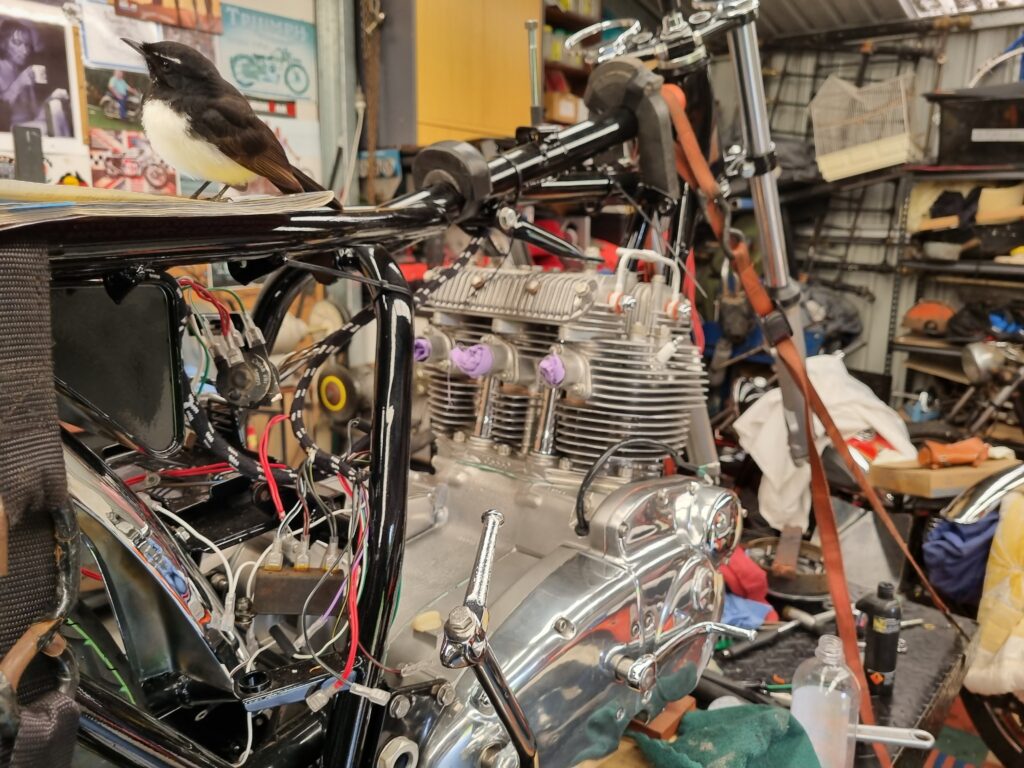

The restoration crept along at glacial pace due to competing projects and financial resources. The frame underwent repairs and paint, the tank was re-chromed and painted, wheels rebuilt etc, but the biggie was the engine. I was hearing all sorts of dross about how difficult BSA/Triumph triples are to rebuild and resolved to err on the side of caution. I already had a good relationship with Ben at British Imports in Malaga so resolved to farm the engine rebuild out to them. It was a good, if not expensive, choice. It also took a while but eventually the engine was built. I made a special trip to Perth to collect a sparkling, better-than-new, 750cc triple engine which, incidentally, weighed a healthy 125 kilograms, or the equivalent of a good-sized poddy calf.

I use the calf analogy because getting a recalcitrant beast into a crush, and a BSA 750 engine into a frame, both require three adults, lots of heaving and shoving and can end up with shit all over the place. But we did it. After an hour of struggle the engine was in the frame and the two blokes helping me are still friends.

Along with a complete rebuild, the engine was treated to a new 5-speed transmission, improved oil transfer with a later model (Triumph T160) oil pickup, Trispark electronic ignition and brand-new Amal Premier carbs. Fuel, spark and compression are the essential elements required in the internal combustion engine, hence, electronic ignition and new carburettors are de rigueur whenever I rebuild a motorcycle. In my experience, they are the best guarantee of easy starting and continued running. Ben also talked me into new camshafts and conrods. One night, with perhaps half a glass of shiraz too many, I clicked on an eBay listing for three new MAP Cycle, forged steel conrods and hit ‘buy it now.’ Instantly, I was $1,000 poorer. Poorer still when Ben said I didn’t want those conrods in my engine so they remain boxed up in my shed (fortunately my wife seldom reads my missives).

With the engine back in the frame I hit the bike with new enthusiasm. By that time, most of the paint and chrome had been done. I lost a good deal of time attempting to relace the wheels before sending them off to a professional, only to learn I had purchased the wrong stainless rims of the UK and they were never going to lace up. It’s probably just as well because I wouldn’t want to ride a motorcycle at 120 mph on wheels laced by Dan Talbot.

The last job was the carbs. When Ben received some new stock in mid-23, I quickly loaded the bike up and returned to Malaga. The deal was already in train as Ben insisted on starting the engine and bedding the rings himself. Apparently, there’s a deft science to it and clumsy, backyard mechanics can glaze the bores if they leave the engine idling in the shed for too long. Added to this, had I not taken the bike back to Ben for a start-up, no warrantee would be offered.

There was a litany of small gaffs and foibles on my behalf but, in my defence, this was my first multi-cylinder restoration. I was at the Albany Hill Climb last November when Ben called to list off all the items requiring attention. The worst was my fancy, three into three exhaust system copied from the Triumph Hurricane (another BSA in Triumph clothing). It was brand-new and had me confounded. Likewise, Ben could not make it fit either. We resolved to cut, weld and re-chrome the offending (middle) pipe, which was luckily only one of the three. The chroming alone cost $450!

Eventually, early this month, I got a call saying the bike was running and ready to go. I dropped everything and headed to Perth. When I arrived, I was given starting instructions and kicked the bike into life on the second swing. She sounds absolutely sublime. Any thoughts of flipping the bike to turn a profit evaporated on the ether of a seductive triple bark exiting the faux Hurricane pipes. For now, this one’s a keeper.

by Dan Talbot | Jun 25, 2023 | Projects, Racing

Over the past thirty years or so of involvement in classic motorcycles I have witnessed the evolution of the spare parts industry as it has gone through various stages to the point where we are now at, with everything we may need merely a click away. I suspect we’ve all had those experiences with the cursor hovering over something that’s far too expensive, one glass of Shiraz too many and ‘click’ it’s mine. Check billet alloy bonnet hinges on my Mustang.

In my experience you need not stop at alloy bonnet hinges, it is possible to build a whole 1966 Mustang, or a 1914 Model T car or a 1948 Vincent twin, entirely from after-market spare parts. Often those parts come from the UK or the US but more and more these days they are made in Taiwan and India.

“The bitterness of poor quality remains long after the sweetness of low price is forgotten” Benjamin Franklin would approve.

If you look at the Mustang just about every body panel you see, except the roof, are Dynacorn pressings out of Taiwan and Mexico. Towards the end of my Mustang restoration, I had a display plate made up that read ‘THESEUS.’ The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that asks if a ship, for example, has had all of its original planks changed during its lifetime is it still fundamentally the same ship? If not, at what point, what number plank, did it cease being the ship of Theseus?

For a time, in fact a long time, the Mustang was driven on a DoT permit bearing the plate THESEUS. This generated enough perplexity to ensure spending a small fortune on the actual DoT plate was not a good idea.

In terms of motorcycles, in 2007 the Vincent Owners Club constructed a complete replica Black Shadow from their parts catalogue. The machine was sold at auction the following year for 34,000GBP, a not an insubstantial amount in 2008 but few would quibble as the machine was made entirely from parts manufactured in the UK. Had those parts been sourced from the Indian subcontinent the machine might not have been so well received.

Spare parts for Ariel and BSA are plentiful and can be delivered from the other side of the world more quickly than the other side of Australia. Due to my leaning towards British motorcycles my path to spares usually begins with local suppliers then extends to the WA metro area before the East Coast of Australia then the UK. At any time during those searches, I can be presented with brand-new, reproduction items, usually out of India.

Reproduction parts are such a big thing these days they even have their own slang: repop. They are made all over the world and, according to some, geography and quality have a direct relationship. I recall, in the days before Ebay, a member of the MG Car Club in Perth wanted a chrome radiator surround. He was informed by a fellow club member that a firm in South Australia was reproducing these items, upon which he was heard to retort, “I will not have any Australian-made junk on my car.” He ordered the piece out of the UK, no doubt at great expense, only to read “Made in Australia” stamped beneath the chrome when he unpacked his newly purchased English radiator surround.

Indian reproduction parts tend to be a bit of a lucky dip. Online chat forums are crowded with arguments for and against the quality of Indian repop spares. I’m going out on a bit of a limb here, but I will wager a good many of the motorcycle spares being sold off in the UK are of Indian origin. For the record, I have had good luck with repop fuel tanks, leather saddles etc so I am usually in the ‘for’ camp.

This tank on the Square Four arrived in Australia chromed and painted for about $500. It is first class quality. The leather seat cover was also sourced from India but the colour had to be toned down with some darker die than shown here.

This brings us neatly to my current rebuild, the Pindan Special, a ’39 Ariel 500 that that I introduced last month.

The Ariel came with a sound fuel tank that had been painted in 1989 and was subsequently set aside, unused. The state of the tank under the paint was unknown but it looked decent, so I really wanted to keep the tank, rather than import a new one out of India. Both the Deluxe and Red Hunter versions of my machine had chromed and painted tanks. To chrome a fuel tank can cost upwards of $1,000 and one can be well into the job before it is even known if the tank can be salvaged. Add another $1,000 for paint and pinstripe and the tank suddenly becomes a very costly item. Further, this machine was never going to be concourse. It’s part Hunter, part Deluxe and part bitza. I also have to keep reminding myself the primary reason for the build is a red dust racer, a bike for tearing across the pindan.

Building a machine for an event that will come around every three or four years is an extravagance in itself, agonizing over decisions to chrome or not to chrome was largely redundant as I could have manufactured in India and landed in WA, painted and chromed, for around $500. That would have been the sensible thing to do but it would irk me every time I saw the original tank sitting on a shelf. In the end, I opted for all-over gloss black, harking back to the VB origins of the machine.

So, to cut to the chase, the tank is back home resplendent in glossy, gloss black with a gold pinstripe – just like half the other machines in my shed. Thanks to Joe at Panelworx in Bunbury, the tank really does look amazing. With the dash panel being finished in chrome, the machine has just the right amount of lustre.

The original tank, dash panel fuel cap and trouble light switch are reunited temporarily before being tucked away to a safe place.

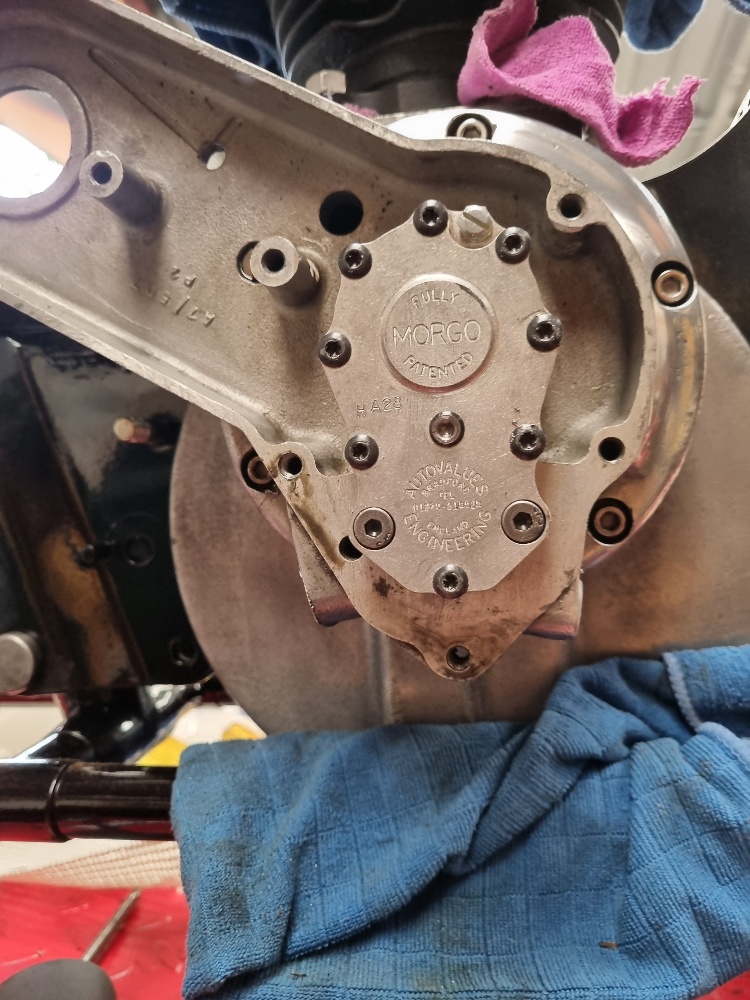

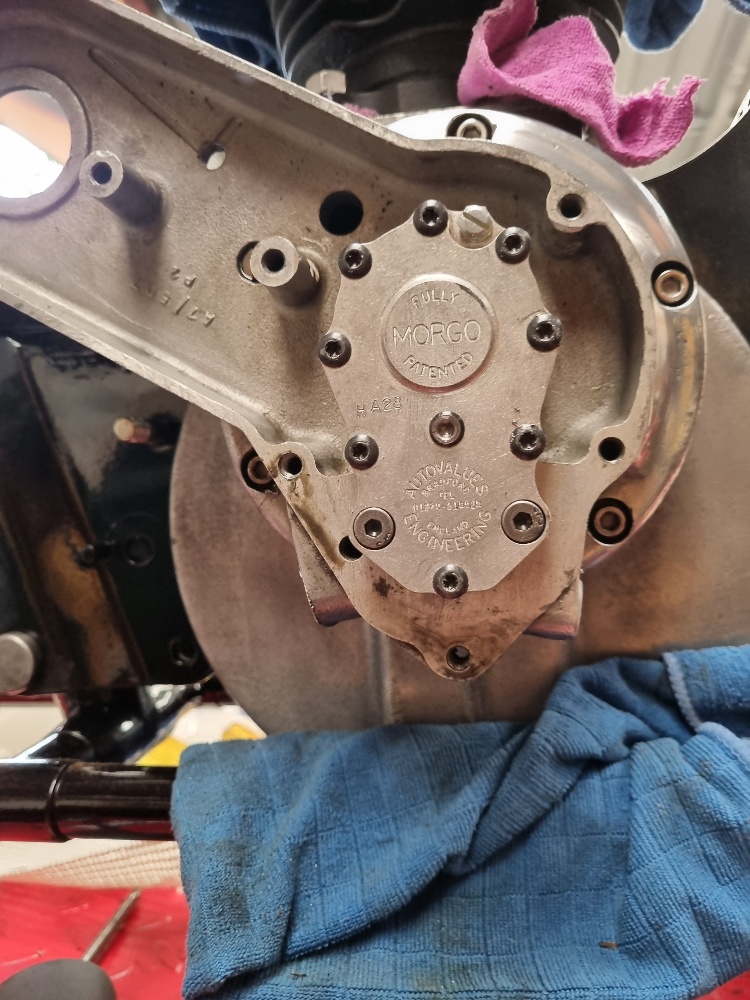

Elsewhere on the bike, I’ve recently fitted a Morgo rotary oil pump. I know this irks some folk who will insist the standard pump, designed about 100 years ago, is entirely sufficient but they are mostly puttering around the UK at 35 mph. I will have my machine pegged to the stop in the Australian desert so she will need all the help it can get and pushing oil through the engine (and the filter I’ve fitted) at twice the original rate is a no-brainer. What does irk me, is that I had to nibble quite a bit of alloy from the internal surfaces of the timing cover where it was fouling on the larger, rotary pump.

Morgo? Certainly more oil going through an engine that will be working very hard.

Newby belt drives and clutches are a work of art. This is one I put on the little Norton a couple of years ago.

Another thing that irks the purists are belt drives. I have secured a Newby belt drive and clutch set up. It is the fourth Newby belt drive that I have purchased and whilst they are quite expensive, they are a work of art. Added to this, the reliability of the belt, the smoothness, the outstanding Newby clutch and, most importantly, a lack of oil in the primary to leak out, are all good reason for choosing the Newby set up. Bob has only done a handful of Ariel conversions so I was flying by the seat of my parts and upon arrive, I soon learned the Newby clutch was too small for the spline on the gearbox main-shaft. I have removed the main-shaft and taken it to Brook Henry, of Vee Two fame, to have a spline cut on the shaft that will match the Newby clutch boss.

On a final note, things are held up a bit waiting on parts to arrive, mainly from the UK but also India.

This after-market oil filter will make a worthy addition to the Special and will provide me with some peace of mind.

I am waiting on bushes to finish this off. The supplier first sent me four, then one and, finally, the last three. Now all of need is to exchange my new stainless spindles.

by Dan Talbot | Jun 5, 2023 | Events, Projects

In continuing the Perkolilli, Red Dust Revival series (Green T), we are now changing from four wheels to two. Green T has been moved on and Perkolilli will now be a two-wheels only affair.

Lake Perkolilli is roughly 40 kilometres North East of Kalgoorlie in, what the International press refer to as: the Australian Outback. The Red Dust Revival is a commemorative event for pre-World War II cars and motorcycles. For those who missed my previous reports, I have again touched on the history of motor-racing at Perko below.

Lake Perkolilli is a flat, vast area some four or five kilometres in circumference, where vegetation has given way to hard-packed salt and clay. It has a colourful racing history dating back to dawn of the automobile. By 1914 there were evidently enough cars and motorcycles in the Eastern Goldfields to form some loose-knit motor racing and Lake Perkolilli was adopted as Western Australia’s first motor racing circuit. In the following few years Perko moved from an isolated, desolate, wasteland to become known as the “Brooklands of the West.” Eventually, tiered grandstands would be built on the location to accommodate the large crowds that would gather to watch the motor racing spectacle. These days there is no hint of the grandstands save for the odd rusty nail that has to be dug from flat tyres (ask me how I know).

Green T has been moved on and we’re going back to Perko with two-wheels next time

Motor racing at Perko was brought to a halt with the outbreak of WWII and didn’t quite return, even with the end of hostilities. This is probably due in part to Caversham airfield being opened to motor racing immediately after the war. Once Caversham became the premier motor racing circuit in Western Australia, Perko became the proclivity of Goldfields revheads and daredevils, hosting both official and unofficial races and speed trials but its status as a race track was lost, until 2014. With the centenary of the first motor races at Perkolilli, veteran and classic race cars and motorcycles returned to Perkolilli for the first Red Dust Revival in September 2014.

Given the cleanliness of these riders and bikes, I’m guessing this was day one at the Perko Red Dust Revival. Nothing stays clean for long.

Not sure exactly what to expect, I resolved to take my 1914 Ford Model T Roadster to Kalgoorlie for a look and see. The event was rained-out but not before I got a good taste of red dust during practice. I have previously been a long-term resident of Kalgoorlie (twice) and a member of the Kalgoorlie Motorcycle Club during the late eighties when I used to suffer the punishment of 500cc, 2-stroke motocrossers we campaigned through the ‘Outback.’ I still have a great affinity for area and the motor sports it generated so it wasn’t long before I was hooked.

In 2019 my wife and I returned to the Perko with our Roadster and again in 2022 with a dedicated Ford T racing car. The problem with veteran racing cars is they are made for drivers from 100 years ago who evidently were of smaller stature than my 6’ 3”. I did manage to squeeze myself into the little race car, dubbed Green T, and I managed many hot laps during race week but when I received an offer for the car that I couldn’t refuse I moved it on with the intention to return to Perko with a larger, V-eight car.

Building a V-eight race car that could be registered and remain faithful to the pre-WW2 requirements of the Red Dust Revival was proving too hard and I quit the project. I have previously documented my troubles with the Department of Transport licensing a slightly modified 1966 Mustang and simply don’t have the energy to take them on all over again – the experience still leaves a bitter taste in my mouth. I sold off the old Flathead V8 that I had retained for the build. I have decided instead to go back to Perko on two wheels.

Red Dust Revival 2022 included 38 motorcycles with over a dozen from the Indian Harley Club. Our members were simply having too much fun and, interestingly, Michael Rock was recording the fastest times of all the bikes on his ’35 BSA 500. Rocky was actually lapping at faster times than the V-twin 1000cc machines out there, and a good deal faster than my Model T.

I have secured a 1939 Ariel 600 and spare 500 engine. The 600 is a side-valve whereas the 500 is the more sportier overhead-valve. Both engines will get a run in the bike from time to time but the 500 will be called upon for Perko duties. All competition machines, bikes and cars, at Perko need to be pre-war so, those with a modicum of history will be aware, this just scrapes in to pre-war so it’s Perko-eligible.

Ariel on the move. The deal has been done and the 600cc Ariel VB is heading to its new home.

It’s a long road to Perko, both literally and metaphorically and my Pindan* Special is far from finished. In fact, it’s barely started, so this seems like an ideal time to chronicle the build.

Although the motorcycle I obtained looked a bit shabby, it bears all the evidence of having been through a sympathetic restoration that was never quite finished. I’m guessing the bike was pushed around various sheds, copping a knock here and there, parked up long enough for rust and corrosion to take hold and paint to begin to flake but the beauty of this machine was below the skin.

The Burman gearbox is full of clean oil and is probably okay however I will be looking inside to ensure the internals are fine.

Popping the head of the bike shows the engine hasn’t been started since it was last rebuilt there is no carbon in the combustion chamber. Down below, there is no sludge, just new, clean oil preserving the freshly turned surfaces. The person I purchased the bike and spares from is unable to say when or who was in there last but a tell-tale sign under the dash panel of the fuel tank hints at it being painted in 1989. The frame, tins and other painted parts are straight and rust-free but have a few scratches compatible more with storage than use. All in all, it’s a small win.

This, to me, indicates the fuel tank was painted in 1989. Evidently, the restoration was never finished and the tank has been left to cop the blows and wows of storage.

The plan from here is to build a road-going Ariel single that conforms with both IHC and 404 tenets of road-going originality, but, with a stock of bits and pieces that can be swapped out when we go racing – just as they did back in the day at Perko.

Back home the old VB is in good company with it’s younger, Red Hunter, sibling. Those familiar with the marque will recognise the non-standard telescopic forks and the (standard) Anstee-link, plunger rear end. In relation to the first point, I have secured an original girder fork contemporaneous with the bike. In relation to the second,1939 was the first year for an optional sprung rear end.

The girder and other bits and pieces have been gathered together in readiness for painting.

*Pindan is a Yamatji word for red-dirt.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 7, 2023 | Uncategorized

Rocket Three Restoration: Part IV

Wow, how time flies. The last time I wrote an update on the Rocket 3 project was almost 12 months ago. In my defense, I have been busy with another big writing project which is done so now it’s back to the Shed.

Since I last wrote about the Rocket there has been quite a bit of progress, most notably the engine is finished and back in the frame. The engine, if I may say so, looks absolutely splendid but I can’t take the credit for it’s rebuild. Some months ago, I boxed up all the parts and delivered them to British Imports in the Perth suburb of Malaga. I have no doubt that I would have been fine assembling the engine but there are so many tales of these old triples flying to pieces when not done right. Added to this, recall last time we discussed the Rocket I expressed an idea I may perhaps keep the bike instead of selling it. I tend to be a little harsh on machinery so I didn’t want to leave anything to chance and I would hate to have to remove it again.

One thing about these engines is their incredible weight. I believe it is somewhere around 125kg. This means, if you don’t want to risk scratching the frame or breaking fins of the engine, at least three people are needed to get the engine back into the frame. It’s a tricky job but we got there. This was also the first time the engine had been introduced to the frame so it was somewhat of a blind-date. The big test in how this two were going to get on was the engine mounting bolts. I’m happy to report, with some gentle persuasion the mounting bolts were settled into place and the engine and frame are living happily together.

The 125 kg engine is, at last, nestled in the frame.

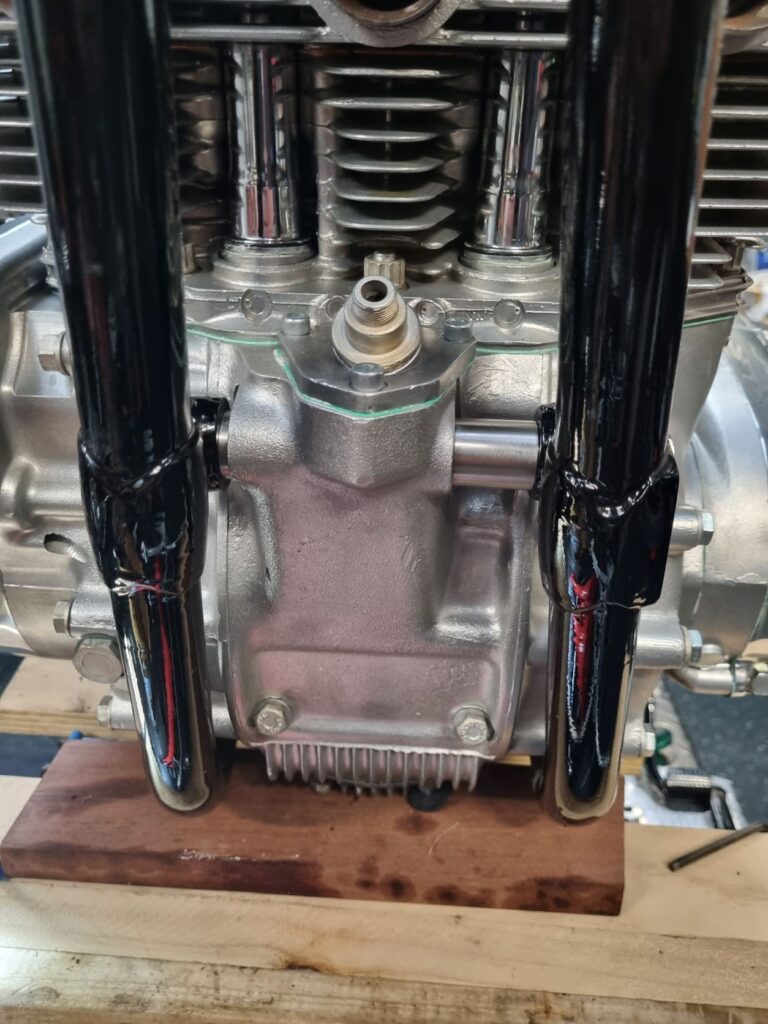

Once the engine is loosely back in the bike it must be shimmed to ensure it is in the best possible position for the chain to line up between the gearbox drive sprocket and the rear wheel sprocket. I did have shims but they were not going to line-up so I went off and purchased some 20mm stainless bar and went off to see Dave my machinist friend who turned out half a dozen shims. Another friend had sent me instructions on how to shim a BSA/Triumph triple engine which helped a lot. Essentially, there is a point at the bottom of the frame where the engine mates to lug and all other shimming must follow. After two more visits to Dave, I had the engine snug against all mounting points.

Three shims were required on the left side of the engine. All of them had to be custom made as we’re inserting a 1971 engine into a 1969 frame.

Shims at the front of the engine. Clearly, the engine is offset but I am assured this is how it should look.

The next job was fitting the wheels. I purposely left them off in case I had to approach the installation by sitting the engine on its side and lowering the frame over it. During some experimentation involving the rear brake spring, I accidently broke the alloy brake plate, necessitating a trip to a welder who was good with alloy for a repair. The hub was then sent to Perth to be refinished. Similarly, the front end could have gone more smoothly but I complicated things.

Evidently I was too heavy-handed in trying to fit a recalcitrant spring to this alloy hub. Never mind, it gave be an excuse to strip that awful powder-coating from this brake backing plate.

Now to find someone who can weld alloy.

The brake backing plate is repaired and in situ.

When BSA restyled the Rocket, for reasons known only to the designers, they fitted a sub-standard brake hub to the front wheel. The result was the earlier Rocket 3 had a superior front brake. I have obtained such a hub with the intention of fitting it to my Thunderbird. I experimented with putting it on the Rocket but it was never going to work – refer to the pictures for more of an explanation. With each change of the wheel, I had to swap the tyre over. It’s been on and off three times now so I will remain with the standard brake for now but I have been collecting bits and pieces to fit disc brakes to the machine so we will see what eventuates.

My experiment in fitting this more effective brake hub didn’t work. It is designed for use with steel fork legs. These later alloy items fouled the mounting point resulting in the air scoop pointing too high.

This is where the problem lay.

Here the bike sits with the conical brake fitted. Due to its ineffectiveness, the conical brake is often referred to as comical.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 7, 2023 | Uncategorized

Tales from the Shed: going down a VB rabbit hole

When we left last month, I had the Vincent dismantled and was feeling quite pleased with myself. If you recall I was washing a few profanities away with a couple of frosty cans of Victoria Bitter.

In my communique I also touched upon the second industrial revolution whilst heading down an internal combustion rabbit hole. Speaking of VB, rabbits and the industrial revolution, it’s timely we paid homage to the Louis Pasteur and his contribution the manufacture of Australian beers. As it turns out, Pasteur was responsible for allowing Australia’s largest brewery to export beer to the world thus the entire population could share in the aroma of subtle fruitiness complimented by sweet maltiness with a slight bitterness to finish (someone out there has just spat a mouthful of Corona over their screen).

So, what has all this got to do with classic British motorcycles? Nothing really, it’s just quite interesting.

Rabbits arrived in this country with the first fleet in 1788 but it wasn’t until 1859 that they became a problem. According to history, a British-born farmer, who wasn’t fond of the Australian fauna released two dozen rabbits, dozens of partridges and a half a dozen hares onto his land in Geelong, Victoria. By 1887 the rabbits hard spread out of control, North to Queensland and West to South Australia, prompting the NSW government to offer a reward of some £25,000 (or, $10M todays’ money) to anyone who could eradicate rabbits from Australia.

Apparently, Louis had been ill and was in need of a few francs so his wife suggested they have a crack at the prize. Louis reckoned he had just the thing, a virulent virus that would wipe out every rabbit on our island continent, but he was both too ill and too busy with things back in Paris so he sent his protégé, nephew Adrien Loir. Their intention was to use chicken cholera bacillus as the infectious agent to kill the rabbits. That’s right, they planned to eradicate rabbits with bird-flu.

Upon arrival in NSW, Dr Loir up the Australian Pasteur Institute on Rodd Island on the Paramatta River in Sydney. The experimentation was carried out under the watchful eyes of the judging committee and was expected to run for twelve months. This came as a bit of a surprise to Dr Loir who only had enough funds for he and his wife to spend a few weeks in Australia so he had to do some urgent fundraising.

Down in Victoria, emerging brewers at Carlsberg Brewery were experimenting with fermentation and sterilisation. One can imagine their excitement when they learned the father of microbiology was establishing an institute in Australia. Dr Loir was invited to Victoria where he was paid handsomely to teach the Australian brewers how to improve their product – right now some readers will be arguing the product has not advanced since 1887. Aside from refining the fermentation process, Dr Loir also taught the brewers advanced sterilisation processes which enabled the beer to be exported to the world in glass bottles.

As it turned out, Pasteur and Loir’s answer to the rabbit problem would not be released. It was thought the disease may harm the domestic avian population. Their idea also came up against opposition by wire manufactures who asserted they could stop the spread of the rodents with their rabbit-proof fences. The NSW government went with that idea but the reward was never paid out as it proved ineffective.

So there you have it, the machinery of the Busted Knuckle Garage is lubricated by the fruits of French scientists Professor Louis Pasteur and Dr Andrien Loir.

Now, back to work, that Vincent is not going to put itself together.

Cheers