“Here was an utterly beautiful engine, lithe, angular and a metallic onomatopoeia for power (Frank Melling, Motorcycle USA).”

Written 82 years ago, when onomatopoeia was a still a thing, Mr Frank Melling had just sampled Triumph’s 500 cc Speed Twin and was clearly impressed with his test ride. Frank was actually saying the Triumph engine sounds as good as it looks and who could argue? The Speed Twin was by any measure a huge success and introduced an engine to the world that would take the company into the eighties.

Such is the success of the modern Triumphs, one could be forgiven for thinking the Thunderbird is a relatively recent addition to the line-up. In truth, the Thunderbird was released in 1949 and gained instant notoriety as a genuine 90 mph superbike and the machine of choice for bad boys around the world, due in no small part to the character portrayed by Marlon Brando in the movie The Wild One. We’ve previously discussed the history of the Thunderbird on the Motor Shed and it can be revisited here. This piece is about the restoration work our Thunderbird has enjoyed since coming into our possession over 20 years ago.

During most of that 20 years I had been looking at my 1956 Triumph Thunderbird thinking, “I’m not happy with the grey frame.” The bike looked pristine when we acquired it but after many years of use and abuse the lustre began to wear off and she became in need of a spruce up, giving me the ideal excuse to pull the bike down and do some colour changing, amongst other things, more important things as it would turn out.

- The all-silver livery of our ’56 Triumph Thunderbird never really grabbed me. What I really wanted was a Blackbird, or so I thought.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, the Thunderbird engine actually needed to be completely pulled apart. With the greatest respect to the person who rebuilt the bike before we acquired it, there’s a critical piece deep within the engine that has a finite operational life and it needs to be replaced with some regularity but is often over-looked. The plan was to pull the engine out, paint, plate and polish every surface and return the Thunderbird to the road as a new machine.

I had a particular fondness for the rare, all black Thunderbird which was sent to America following the popularity generated by Brando’s gleaming black 1950 machine – in a black and white movie of all things! Long before Honda came out with their four cylinder, plastic-enclosed behemoth, the all black 650cc Thunderbird was dubbed the ‘Blackbird.’ And it’s a stunning machine. Rich, black paint contrasts well with polished alloy and, as is the case with classic machines, highlights the era perfectly. Yep, my ’56 was going black.

- Stunning in black and polished alloy this limited release Thunderbird was dubbed the Blackbird. Photograph provided by Thomas Duffy, the owner of this beautiful machine.

In the weeks and months leading up to me beginning the restoration, trawling through the internet of things I stumbled upon a rare colour combination of silver on black. The bike had been restored by Choppahead Kustom Cycles in Massachusetts and it is the perfect embodiment of the classic Triumph that has been with us since Edward Turner unleashed his famous Speed Twin on a world seeking beauty and performance in a motorcycle. I could no longer look at my all-over silver Triumph in the same way and even the hitherto lusted-over Blackbird became merely a crow. I had moved through the various mental stages of change (you know; procrastination, contemplation) and now it was time for action.

- This ’56 Thunderbird was restored by Choppahead Kustom Cycles of Freetown, Massachusetts. Once I laid my eyes on this bike thoughts of a Blackbird were lost to the ether of my mind. Special thanks to Choppahead for allowing me to use this photograph.

Twenty-something years of use had left its mark in the form of paint chips, faded chrome and rust starting to show through here and there. I was further able to justify the pull-down by claiming the oil leaks needed to be fixed (I’m serious), the magneto needed attention and the cleanliness, or otherwise, of the infamous sludge-trap, was an unknown. Now, I’m the first to agree the term ‘sludge-trap’ has a fictional tone but it is a real thing and ignoring it can destroy a classic Triumph engine, it is the critical piece I mentioned above. In the days before oil filters, some manufactures, in the interest of engine longevity, put a screen filter inside the crankshaft oil circuit. So, let’s have a little think about that – the oil filter is inside the crankshaft. Anyone with a modicum of knowledge around the construction of the internal combustion engine will recognise the inherent problem around this design.

When we first purchased the Thunderbird it looked brand new. Attention to detail was amazing and it ran really well but there was a couple of tell-tale signs of trouble brewing deep inside. Clearly the magneto hadn’t been touched. Once the bike heated up it was extremely difficult to start which is a sign the maggy is on its way out. In a world governed by constants, temperature coefficient of resistance left me having to give the warmed-up 650 an extra, extra hard kick to overcome the resistance of the hot maggy coils in the hope I could generate a spark strong enough to start the engine. Once started, the ancient twin would squirt oil everywhere, including all over my jeans and boots. Oil would shoot out of places hitherto unknown to contain oil or require lubrication. Seriously, oil would somehow hit the bottom of the fuel tank then run of the seams making it look like the tank had its own secret oil reservoir. A degrease and polish would have the bike looking a million bucks but that would only last as long as a decent ride.

So there you have it, sludge-trap, magneto, oil leaks and beautification were my motivation. The Thunderbird was pushed onto the hoist, anaesthetic was administered and she went under for some major surgery. It’s not as if I had nothing to do. My Mustang rebuild was languishing away quietly in the corner of the shed, my Triton, like an insecure toddler, was in constant need of attention but, by crikey, that Thunderbird was coming apart.

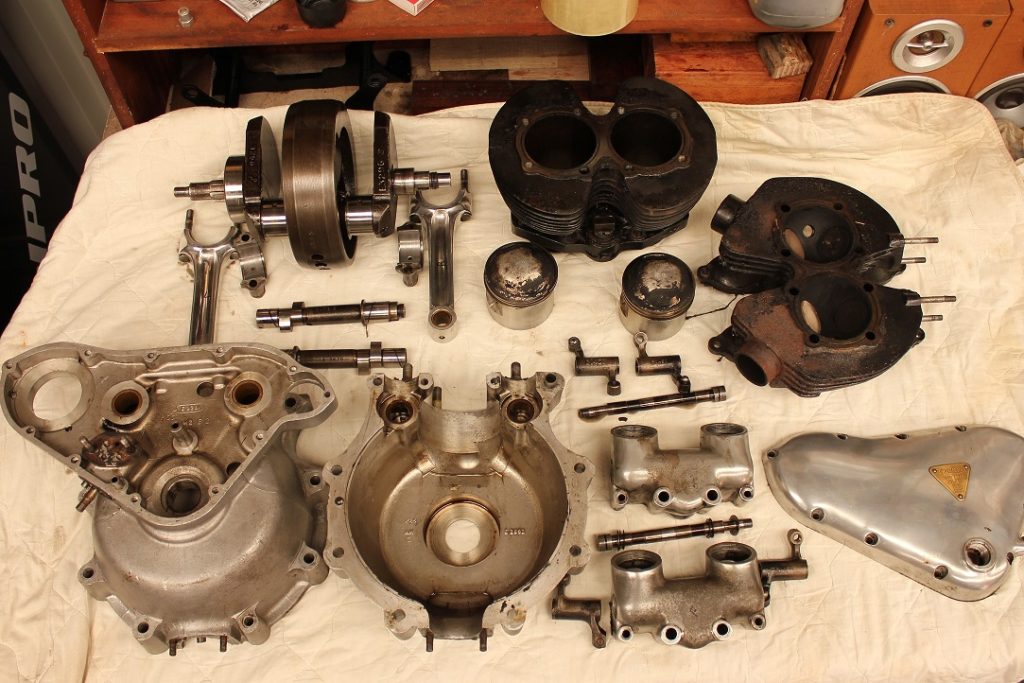

The bike came apart reasonably easily. It was grubby behind all the surfaces that I couldn’t reach with my very thorough detailing but built up oil and grease does wonders for preserving the metal on which it cohabitates. When it came time to turn my attention to the engine, that too came apart really well. There are some specialist tools required and I purchased some and borrowed others. Eventually, I had the engine, in fact the whole bike, down to irreducible parts, in other words, every last nut and bolt had been removed.

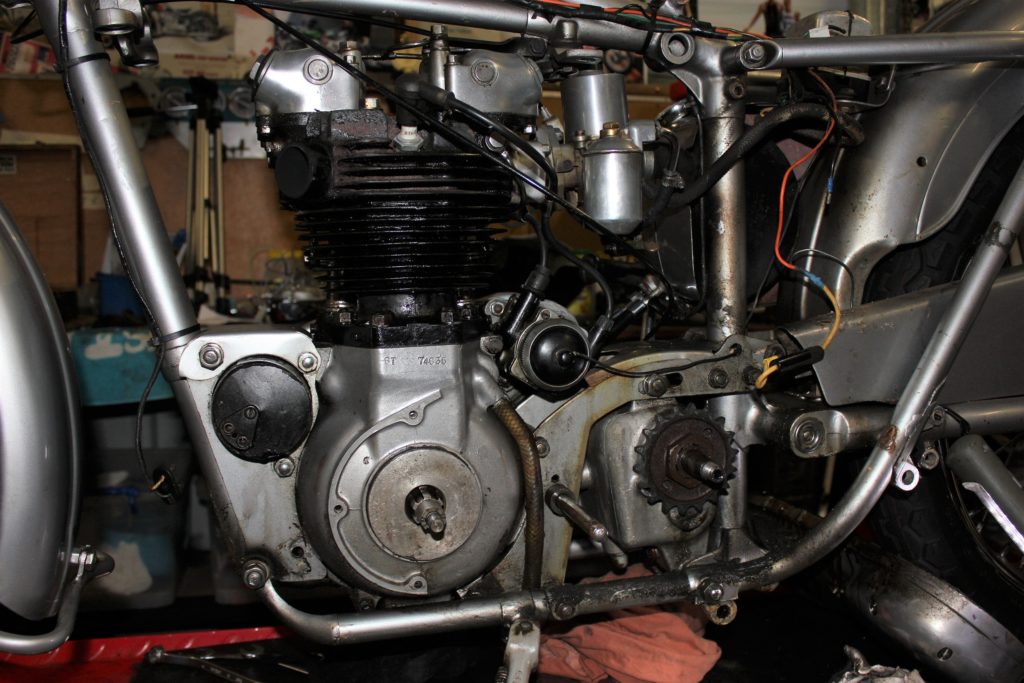

The venerable Triumph parallel twin has been with us for over 80 years since it was introduced to the world as the 500 cc Speed Twin. In 1949 the engine grew to 650 cc in the Thunderbird. Note the SU carburettor. In the mid-fifties Triumph experimented with these carbs and they proved successful but were possibly too expensive to continue with.

- The 650 cc engine.

I was more than happy to learn the big-end bearings were marked as “std” which indicated the crank had never been ground. Bonus. The bearings were also stamped with 08JU90 so I could safely say the engine had been rebuilt sometime between 1990 and 1993. Recall from part I, we bought this bike after it had been restored, sold to an intermediary, sent to the UK where it sat in a container for two years before being returned to WA.

The pistons were .20 over which indicates in 62 years the bike had only undergone one rebore. I began to think ‘maybe new pistons, rings and bearing would be enough.’ And maybe not. Here I was contemplating ignoring one of the primary reasons I pulled the engine apart, mainly because I was out of my depth. The crank would need to be handed over to the experts to expunge the sludge, of which, there was plenty. Like the tailings from of some black gold mine, the substance had a hint of a sparkle from decades of engine grinds mixing with mud and other impurities. Just as well we looked.

- The sludge removed from deep within the crankshaft of my Thunderbird had a hint of a sparkle from decades of engine grinds mixing with mud and other impurities.

- The engine is out of the bike and about to be pulled apart. Note the ever-present camera which will record the proceedings with about 500 photographs, a practise that has proven invaluable over the years.

- Back in the nineties the Thunderbird was a bit of a farm-hack on our family property.

- 20 years later, same motorcycle, same kids.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks