When we left off with the last instalment, the little Norton was parted out here, there and everywhere. Readers and interested parties will be happy to know most of those parts have been renewed and, if not back together, they’re at least back in the shed. One such ‘part’ is the engine.

For a 350 cc machine, the engine in the little Norton is a substantial lump of iron and alloy. This is understandable as essentially the engine started out as a 500, only the internals are different. In fact, the whole bike is basically a 500 ES2, albeit with 350cc. This actually makes it quite rare. By the mid nineteen-fifties young men in the UK were craving larger capacity machines and would overlook the M50 in favour of its big brother. Many of the 350 cc bikes that were purchased had the single cylinder engine taken out in favour of a larger twin, such as that found in the Motor Shed Triton.

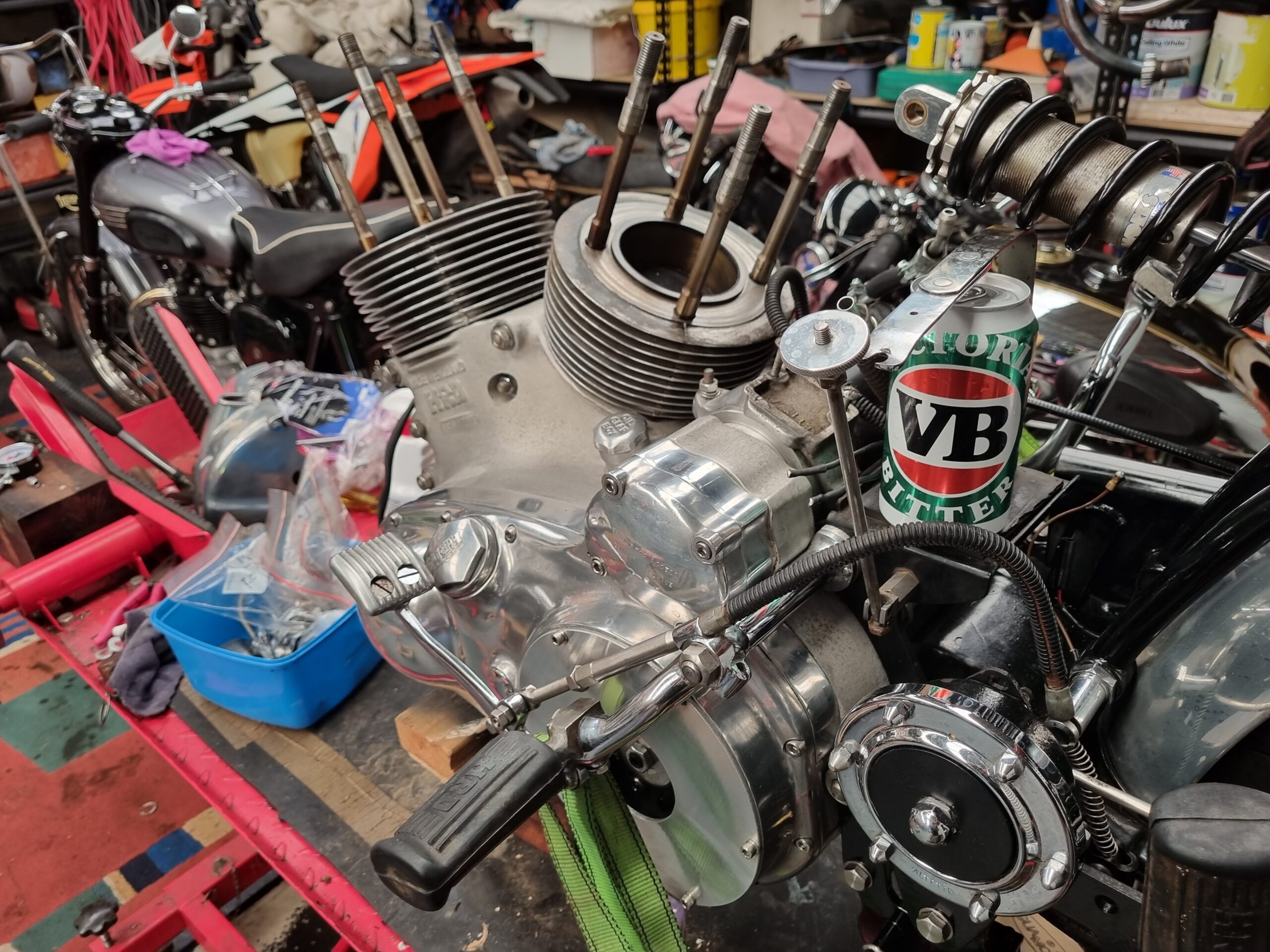

The 350 cc Norton single.

You’ll recall the story of the Triton, a parts bin special created by throwing a Triumph twin engine in a Norton frame? The featherbed frame, which is discussed at length in the Triton story, was a huge success for Norton. The twin down-tube, cradle style frame was to become the signature to the Norton motorcycle racing effort. They had long proven they had the best engines, the featherbed frames simply helped the company assert their racing credibilities and maintain their dominance in the two-wheeled, racing world (I’m sure that’s poke a hornet’s nest so hit me with your best shot :).

Elsewhere in the range, the single down-tube frames were left for commuters, tourers and those wishing to fit sidecars – which were a big thing in Britain as the country recovered post-war. The Buz Norton is of the second group, not a risk of losing it’s engine older, single down-tube, ‘pre-featherbed’ frame. I say this in parenthesis because they were never actually referred to as pre-featherbed,’ this is a retonym used by various people and groups, such as parts suppliers – some of whom I’ve become intimately acquainted with.

The fuel tank, single down-tube frame and engine before restoration. Note the sidecar lugs on the frame (visible near each end of the fuel tank).

Andover Norton has been the preferred parts supplier. They are very fast in getting gear out to Australia but as far as the singles go, parts are limited. I’ve also found the catalogue is not too accurate, which has resulted in me receiving an axle that doesn’t fit. “And where’s the original axle?” I hear out there on the ether. Being a basket case, which by definition is a jumble of bits and pieces, some things have inevitable gone missing. The rear axle being one such item.

One of the hazards of international purchases, they don’t always fit.

Speaking of axles, we have two freshly build wheels waiting to be fixed to the machine. They are brand-new, stainless rims and spokes laced to freshly vapour-blasted hubs. They look fabulous. Shiny, but not too so. The modern rims and spokes, together with the original, sturdy hubs have resulted in some tidy rolling stock. It will be a long time before these wheels wear out.

The new front wheel. It will be a long time before this one ever wears out.

Elsewhere on the bike, having done the math, it was economically and mechanically sound to dispense with all the broken and rusty clutch parts in favour of the beautifully crafted Bob Newby belt drive. These things are a work of art that would ordinarily over-capitalise such a machine as the M50 but there was simple nothing that could be salvaged from the original clutch so picking up a Newby belt drive and clutch set up has saved money, added reliability to the bike and lessens the likelihood of oil escaping the primary, because there’s simply none in there.

The Newby belt drive. A work of art that, sadly, won’t be seen.

The engine is snugged up, back in its rightful place. With vapour blasting shining all the alloy pieces and a lick of pain or plating on the metal components, the engine is looking as good, if not better than new. Plating consist of chrome or cadmium, the former costs a king’s ransom, the latter is not so bad. Like other forms of metallurgy, chrome plating, when done right, is of much higher quality than in the days when the Norton first travelled along the production line, which is what we’re aiming for with the whole bike.

Metalwork prior to cadmium plating.

Metalwork after cad plating.

Engine top end – before.

Engine top end – after.

Chrome-plated items.

The rear guard is back from the painters and is so shiny you could do your hair in the reflection.

Hi Dan, looking good, hate to think of what the final cost will be, I’m just starting to rebuild a 54 M50 hoping not to spend as much as you though. I suspect the rear axle you got is the right one it doesn’t go right across the swinging arm but screws into another axle piece in the rear hub. Keep up the good work it will be wat better than new. Cheers, Bruce.

Thanks Bruce, the motorcycle came to me as a basket case so it’s helpful to hear from people who know about these things. I’m rebuilding it for the Busby Family, two of whom have commented above. This motorcycle has a very special place in their heart.

Wow, Dan this really is an exciting time for ‘Buz’ Norton.

Shirley

Looks amazing Dan. So good to be able to read along with the project! You would have made Dad proud 🙂