by Dan Talbot | Mar 23, 2019 | Collection, Projects

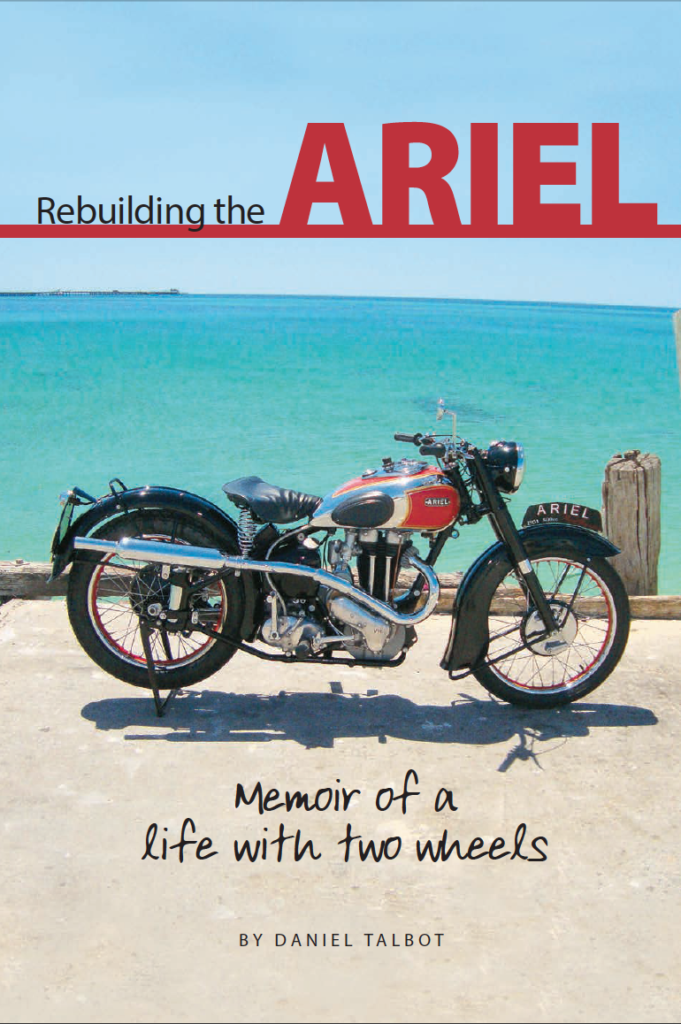

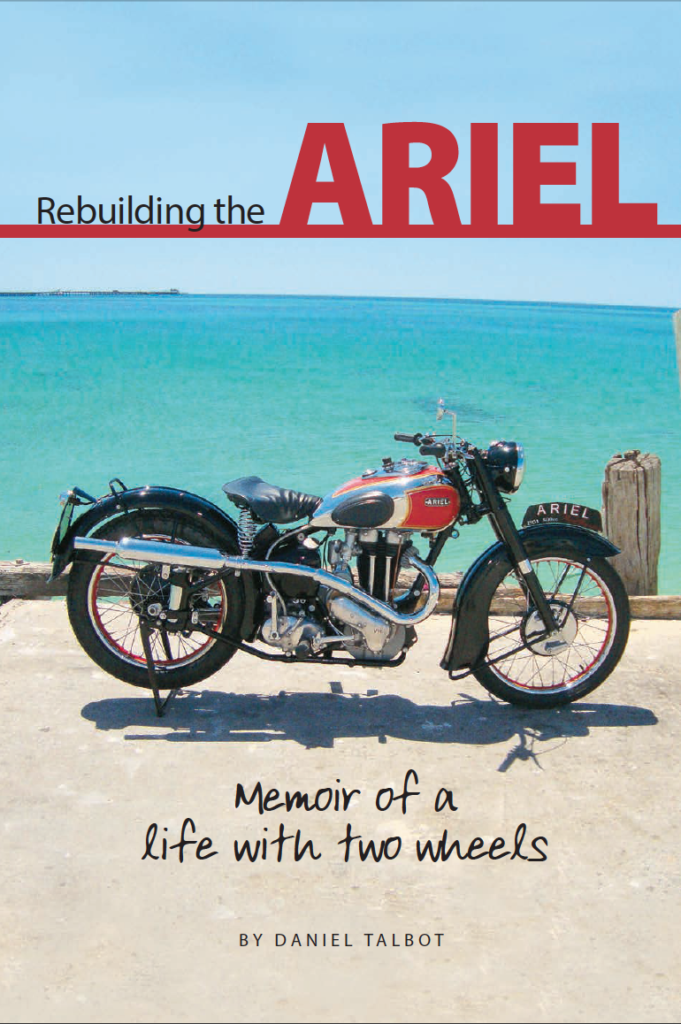

Rebuilding the Ariel Part II

This is the second instalment from “Rebuilding the Ariel,” available on this site in eBook format.

Given this is only our second excerpt from Rebuilding the Ariel it is perhaps timely to have a brief discussion around the origins of the name Ariel. It’s no secret I love all things with two wheels, including bicycles, in fact, I have a particular fondness for the original bicycle: the penny farthing. There you go, it’s out there. I feel better having got that off my chest.

James Starley, the so-called ‘farther of the cycle industry,’ conceived the penny farthing and named it “Ariel,” after the character Ariel, the ‘spirit of the air,’ who was immortalised in Shakespeare’s sonnet “The Tempest.” In the Tempest, Ariel is a sprite who possess magical powers which, essentially, he uses for good. Ariel is powerful, agile and a loyal servant. It is easy to see how one may be inclined to name a motorcycle after such a character yet Starley chose this name some thirty years before the motorcycle came into existence.

Starley’s ungainly cycle, with its huge front wheel is neither powerful nor agile, however, one is indeed perched quite some way up in the air so perhaps that is what he had in mind. Starley’s hypothesis is as brilliant as it is simple. He found that by increasing the size of the driven wheel one could travel further with each turn of the legs. Naturally this simple form of mechanics was later made redundant through the advent of chain-driven gear system, another brilliant idea out of the Starley family, this time with the help of William Hillman, the founding father of the automobile that bears his name.

The new chain driven cycles were appropriately named the ‘safety bicycle’ as it put an end to riders toppling over the handlebars on out-of-control penny farthings, which were retrospectively named ‘ordinary bicycles,’ as opposed to the ‘unsafe,’ ‘dangerous,’ or ‘you must be crazy to ride this,’ bicycle.

Starley’s hypothesis is as brilliant as it is simple. He found that by increasing the size of the driven wheel one could travel further with each turn of the legs. Eventually, the wheel would grow too big for one to turn it. This is my old 55 inch wheel. I have now gone to a 58 inch Bolwell bicycle, which is a big wheel.

Starley passed away in 1881 leaving his sons to carry on the legacy of the Ariel although it was his nephew, John Kemp Starley, who also a member of the cycle production team that is credited with using Hillman’s idea to invent the chain-driven safety bicycle which was named the Rover, giving rise to the famous British motor vehicle company of the same name. Eventually the organisation became known as the Ariel Motorcycle Company with Ariel producing its first piston-powered machine in 1902, sadly after the death of Kemp Starley whose vision was firmly set on the motorcycle industry.

Shakespeare’s Ariel was said to be able to work up a storm, a tempest, sufficient enough to shipwreck the King of Naples and his crew. After providing loyal service to the magician Prospero, and having been freed from 12 years imprisonment at the behest of the witch Sycorax, Ariel is set free, hence, we have a loyal, powerful and free spirit giving its name to a motorcycle, presumedly with the same qualities. Now, back to our Ariel. We left off previously with me parking the bike up without having crashed it during my maiden voyage.

On reflection, I realise that Ariel was like nothing I had ridden ever before. Even before you start riding, the bike lets you know it’s different. The broad saddle, ‘tear-drop’ fuel tank with big rubber pads for the knees to prop against, bulbous front guard, an odd-looking instrument panel in the centre of the fuel tank are just some of the antiquities associated the motorcycle. Bakerlite switch-gear and an abundance of chrome-plating also let me know this machine was different from the modern machines I was familiar with.

When introduced to the Ariel I was still at the age where performance and looks counted for a lot in a motorcycle and, to me, the Ariel had neither. As I write this piece, almost three decades since that first trepid ride, and with lots of equally hair-raising and fun times spent on the Ariel, I now tend to think it is perhaps one of the most handsome machines ever made. Red paint upon chrome, gold pin-stripe and a black frame, add up to a visually stunning motorcycle. Take a look at the photographs and tell me you disagree (comments are welcome in the box below).

Back then, I loved dirt-bike racing and road-riding with equal measure, I still do, but in recent times I’ve returned to the more pure form of cycling – that which is without an engine. I trust these pages will attest to my twin passions of motorcycling and bicycling, for me, it matters not how much power is contained within my machine, if it’s on two-wheels I’m all for it.

Around the time I took my first excursion on the Red Hunter, I was quite heavily involved in bicycle racing and triathlon. I still love my cycle racing and can think of nothing better than to flog myself for six hours on a bicycle and, to do any good, we must train, which means I often spend more time riding bicycles than I do motorcycles.

Yep, we race bicycles – including these.

We race motorcycles too. If it’s got two wheels we’ll give it a go.

As I write this (wrote this), with the Ariel undergoing restoration (now finished), I wonder if it will see any more use than the half a dozen rides per year that the two other operational machines in my garage get to see. My friends jokingly comment I need a new battery every time I want to ride my modern Triumph. The older Triumph has a kick starter so a flat battery doesn’t prevent me from riding it. It makes little difference to me whether I ride my motorcycles or not, the important thing is they are there, ready to go, should the urge take me. I also like my bikes to be in top condition, even if they are dormant, and the Ariel has been in a rather poor condition for some time now. Postscript; there is now seven motorcycles in the shed and they still battle against my bicycles for time in the saddle.

Dad purchased the Ariel sight unseen out of Tasmania. As stated earlier, he bought it because he had one when he was a young fellow. The Red Hunter was one of the more desirable motorcycles of his era and about the time Dad turned 17 years of age he managed to secure a very nice example out of Bays’ Motorcycles in Perth. Evidently Dad’s father paid for his first Red Hunter so it’s fitting that I have managed to purloin this example from his grasp (more on that later).

By the time Dad acquired his first Ariel, the Red Hunter had been in production for about 20 years, having made a stunning debut at the Earls Court Motorcycle Show in 1931. The Red Hunter came in both 350 and 500cc variants and was known right from the start as a sports machine. That Ariel remained in production through two world wars, the Great Depression and some major company restructuring speaks volumes for the durability of the machinery produced by the company. In a further demonstration of durability, the official production run for the Red Hunter was 27 years, from 1932 to 1959.

Despite the Ariel being both a capable and desirable motorcycle, what Dad truly longed for was a Triumph Thunderbird. With its larger 650 cc twin cylinder engine, the Thunderbird was known as a true superbike of the era, capable of 100 miles per hour. As it turned out, he would have to wait another 40 odd years before the Thunderbird dream was to be realised.

In 2019, I’m happy to attest both the Ariel and the Thunderbird remain with me.

To be continued, or you can buy the book, in eBook or hardcopy format.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 23, 2019 | Collection, Projects

Taking up from where we put the torch down, the Mustang had panel after panel peeled off until it has hardly recognisable. The floor was the first to go with the new single piece, front and rear, going in.

A ‘new’ floor is exactly that. Pressed from a single sheet of metal in Thailand, Mexico or Canada, most of the panels that went into the Mustang were manufactured by Dynacorn. It is actually possible to purchase a whole body from Dynacorn. Sadly, that won’t work in Australia as, apart from needing a fat cheque-book, any car built using a new body would have to pass as a current model with all the emission restrictions and safety requirements that would bring before it could be registered, unless, of course, you had a sacrificial chassis number with import approval etc. I’m sure that happens, but not in my case, my car is a piece of Aussie motoring history and I needed to retain as much of it as possible.

To remove the floor large portions of metal had to be cut out and tossed on the scrap heap. With the large portions removed the spot-welds can be accessed and burnt off without destroying (too much of) the metal beneath: that is, the portion we want to keep. Spot welds can be drilled out but on something as large as the floor there are dozens of the bloody things so drilling would have been labour intensive, nope, better just to blow it away.

That’s a major portion of the car missing right there. Note the bracing. Without this the car would probably have collapsed.

With the metal all cleaned up, it was time to fit the new floor. Recall the body is securely braced so she won’t suffer any structural movement between the old floor being cut off and the new one going in. Further to this, we had thoroughly measured the whole body, back to front, up and down, inside and out, and recorded the measurements in both a book and on the metal.

With the floor roughly in place, it was time to pummel it with tek-screws. Joe kept belting them through my precious-metal like there was no tomorrow, the underside of the car looked like a bloody porcupine! I would later come to love the simplicity of holding everything in place with the humble tek-screw, a marvellous invention.

We’re jumping ahead here but those two stubby chassis rails would later be connected to the rear pair, with two pieces of metal pressed for the purpose, adding immensely to the torsional rigidity of the body. Something Ford should have done when they built the car.

The brand new floor waiting to go in.

The new floor went in quite easily, tricking me into thinking all the new panels would similarly go together.

The new floor is held in place by tek-screws ahead of welding.

Conveniently, there was another, recently painted 1965 Mustang in Joe’s workshop waiting to be refitted. It was in a separate shed and many was the time I traipsed across to the other shed, tape measure and notebook in hand, to measure and record the dimensions of the ‘65 couple, which is essentially the same body as my ‘66.

I used to look at the finished ’65 and marvel at the lush silver paintwork dreaming of the day mine would look that good again. In time it would, but we had a lot of work ahead of us.

Always have access to another car for reference purposes.

What we’ve learnt

- Said before and repeated here, brace the car!

- Measure, remeasure and measure again.

- One cannot make too many recordings of the body dimensions.

- Tek-screws are your friend.

- Finally, have another, intact, car nearby for reference purposes.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 19, 2019 | Collection

The Norton Commando emerges from the shed, liberated at last.

As a motorcycle journeyman I have, for most of my, life been chasing maximum power from my machines, I still vividly remember the first time I cracked 100 horsepower. It was the year 2000 and my new Triumph Sprint, which was in fact a 1999 model, produced 107 horses. It was unbelievably powerful and, had I not been so responsible (LOL), I could have wound up in all sorts of trouble on that bike with its top speed of 220 km/h. Some time later, in 2010, my Triumph 1050 Sprint produced a whopping 120 horsepower, and on it goes. So, it came as a surprise to me, and the great mirth to my motorcycle riding buddies, when I purchased my 2015 Norton Commando, and in the process, dropping back to 79 horsepower.

A stunning looking machine but not great out of the box.

So how can losing all that power be even remotely exciting I hear you ask. I must say, I asked myself the same question many times as I contemplated purchasing the Norton. At the end of the day sheer good looks and nostalgia won out but, as I sit here typing this, still feeling the buzz of 250 spirited kilometres on my Norton I can honestly say the way that bike delivers the goods is thoroughly exhilarating. Mind you, it hasn’t always been that good. In the 12 months I’ve owned by Norton, I’ve taken it from a choke-up, lack-lustre performance void to something akin to naked aggression, let me explain.

One of the most famous names in all motorcycledom.

When I finally hit the road on my Norton the engine had less than 100 kilometres on. It had, for about two years, been used for display purposes only. Firstly, in the dealership then in the first owner’s lounge-room and, as far as I can tell, was only ever started for amusement purposes. The first few rides I had left me with a kind of sinking dread. The bike surged and misfired at anything under 3,000 rpm and wasn’t so good above that range either. Put simply, it was horrible.

With no distributor on the West Coast, or, at that time, anywhere in Australia, I had to rely entirely upon my own skills to tune and fettle the engine. I turned to the only place one can in times like these – the internet. By modern-day standards the Norton is a fairly basic, push-rod, parallel twin cylinder engine. The major complication is fuel injection and the associated computer hardware and software. Even as I write this piece, with the bike running beautifully, I can’t help but pine for good-old carburettors.

The more I researched running problems associated with the new Norton twins the deeper the quagmire of responses grew. I managed to slough the fiction from the fact and quickly learned who knew what they were talking about, and who didn’t, in my favoured forums and sites for technical assistance. What I found early was the scourge of the European Emission Standards. Essentially, the Norton engine pretty much resembles that which rolled out of Birmingham in the form of the 500cc Norton Dominator in 1949, albeit with modern-day construction and materials. The Domi engine grew through various stages of 650, 750 and, finally, 850 cubic centimetres before the Commando was retired in 1977. Of course Norton and the famous Commando name has been revitalised in the modern machine I now own. How we got to this machine being re-released is a long story and one we shall revisit soon, but, for now, it is the modern incarnation we’re concerned with.

Even the name sounds cool to this long time devotee.

To get the bike through the Euro emissions Norton fit fuel injection and keep the smog to acceptable levels. Acceptable levels these days is generally where the air coming out of the exhaust is cleaner that that which goes into the engine! Remember this has a seventy-year heritage, it is like handing grandpa an iPhone. The get the grand old design to perform I replaced the coils, spark plug leads, spark plugs, cam position sensor and cleaned the fuel circuit of the detritus that was once petrol. I may have broken a few Euro standards but, heck, we’re not in Europe!

With each change the bike made incremental improvements, but nothing startling and nothing to help ease the knot in the pit of my stomach that was screaming out ‘what have you done?’

It became obvious I would eventually have to hand over my bike to someone versed in the twin arts of fuel system management and computer science. To me fuel circuit mapping is the proclivity of NASA boffins but unfortunately, it’s something we live with every time we start an engine that has been manufactured this century. We don’t have NASA in Australia, cripes, at that time we didn’t even have Norton in Australia. The only solution was for me to travel to Norton with my ECU in one hand credit card in the other. That’s Norton in the UK, a heck of a long way from Western Australia.

Donington Hall, hallowed ground nestled between Donington Castle and Donington race circuit.

We’ll see about that!

It was my intention to collect two sports mufflers from Norton and have the ECU mapped to suit, I wasn’t to be disappointed. Pretty soon after walking into Norton headquarters my bubble-wrapped mufflers were handed to me, ready to be stowed in my suitcase ahead of our flight home. The combine weight of the two sparkling new, stainless mufflers was less than 5 kg (which enable me to also pack a new barrel and pistons for one of my other bikes). My ECU was remapped whilst my wife and I sat in the waiting room with a Norton used in a recent James Bond movie as company.

Nortons are no longer assembled in dank, drafty sheds in Birmingham. The new facility is something akin to Downton Abby. Outside Donington Hall looks like a manor house, inside it is a modern, slick operation that reassures me the future of Norton is in good hands. Donington Hall is wedged on a parcel of land between Donington Racing Circuit and Castle Donington, a small town of about 6,000 inhabitants in Leicestershire, England. So plush is the facility, Norton CEO Stuart Garner actually lives there. Stuart’s Aston Martin, bearing the numberplate NOR7ON (sic), sits immediately outside his apartment. Until recently, Aussie Road Racing star Davo Johnson also lived there.

After collection my mufflers and newly flashed ECU, my wife and I went on a tour of the factory, whilst it was in full swing. Workers were pouring over partially assembled 961 twins – of which there were just three on the production line. The machines were exactly the same as mine yet I still felt a pang of envy of the new owners, such is the allure of the Norton.

In keeping with the original style of the Commando, the designers have reached a pleasing symmetry between engine and frame. The frame is slim and the engine tall which, essentially makes the bike feel large. At 6’ 3” the bike fits me perfectly and my feet are easily planted on the ground but shorter people might not feel so comfortable, however, any thoughts of comfort would likely be lost when the big twin is spun into life.

Talking of spinning, 270 degrees is the new black in engine layout. Triumph have been doing it for a while, the new Royal Enfield 650 will have it and Yamaha have known it for decades in their 850 parallel twins. Manufactures have come to understand the value in firing a twin at 270 and 450 degrees, emulating the characteristics of a Ducati L twin, namely a much smoother and more useful spread of power than the previous 360-degree firing order the British twins are known for, it just needs to be freed up, electronically in the ECU and physically in the exhaust. Fuel in, waste out, simple. Well eventually.

Back home and the stubby Norton sports mufflers are on. They take some getting used to but the sound is oh so sweet.

When I got home, I plugged my ECU back in, fitted the new mufflers and hit the starter. Bang, she’s alive, rorty and responsive. The ride was a revelation, a great improvement over previous sorties. The great lump of almost 1000 cc in a parallel twin is usable, sounds awesome and doesn’t shake me to pieces, not quite. The Norton has a balance shaft but it still vibrates and vibrations might not be everyone’s cup of Early Grey. If you love a silky-smooth, multi cylinder bike you’ll probably not enjoy the Norton. I like to know there’s a big engine propelling me forward and the Norton delivers that feeling in spades. I love it.

One thing I’m not so fond of is the five-speed gearbox. The box feels solid and changes with all the precision of a rifle bolt, but, out on the road in top gear, I find I’m frequently looking for another cog. It’s early days for me and the Norton but I do wonder, in this day and age where six speeds are the norm, why Norton has stuck with a five-speed transmission.

The new mufflers have been a very good investment. Combined with the re-mapped ECU, the engine now runs smooth and clean. The jerkiness of the overly lean ECU is gone, as is the strangled sound previously emitted from the large pea-shooter style, stock mufflers, although, if I have one criticism, I’m not sure why the pea-shooter could not be replicated in the sports muffler, instead of the stubby tubes the factory produces. That aside, the sound coming from those stubby tubes is sublime. On over-run the pipes emit a deep baritone burble and it sounds amazing, it’s enough to have me pegging the bike just to hear the bellow and growls the big twin makes, I know, I sound like a teenager.

All in all, I’m well pleased with the bike as it is now. It’s taken a bit to get it to this stage and one might well ask if it’s worth it when I could have purchased a new 1200 Bonneville and saved bucket loads of money. With each new ride the value of the machine is making itself felt. Recently I was out riding with some friends and I found I was pushing the Norton up into revs and speeds that I had previously stayed away from, as much for some perceived fragility as anything else, but the harder the bike is pushed the more she shines. After two days of spirited riding I tucked the Norton back in the shed with a self-satisfied grin that has been a long time in the making.

Yep, she may have little more than 80 horsepower but I reckon they must be Clydesdales!

With the Norton at last running fast and free I’m well pleased with the performance, albeit with a scant 80 horsepower. Check out that grin!

by Dan Talbot | Feb 13, 2019 | Collection, Projects

Those keen of eye may have noticed frequent references in various Motor Shed discourse about our ’56, 650 Triumph Thunderbird. The bike certainly comes in for a mention in Rebuilding the Ariel so we thought it was time to string some excerpts together from the book to keep the Triumph fans out there happy.

The star of Rebuilding the Ariel is, of course, an Ariel motorcycle. It is another one of my father’s former bikes purchased out of Tasmania in 1989 because Dad had one when he was 17 and felt like revisiting his youth again at the age of 55. Despite the Ariel being both a capable and desirable motorcycle during my father’s youth, what Dad truly longed for was a Triumph Thunderbird. With its larger 650 cc twin cylinder engine, the Thunderbird was known as a true superbike of the era, capable of 100 miles per hour.

This photograph was taken in 2010, after about 12 years ownership. The bike still scrubbed up okay but oil easily found its liberty and rust was forming on the barrels.

Dad finally managed to secure a Thunderbird a few years after the Ariel. It was a particularly nice example of a 1956 machine. The motorcycle is fitted with an English SU carburettor and finished in all-over silver, including the frame, which I was told indicates it was an export destined for Australia but I have since discovered that to be a myth. There are a few other myths about Thunderbirds that should be cleared up, or at least introduced here.

The original Thunderbird, if indeed there can be such a thing, was not a motorcycle, nor was it a Ford convertible, it was a creature from within the culture of the indigenous people of North America, a mythical giant bird that was able to cause the sound of thunder by flapping its wings together. It combined the freedom of being able to take to the air with power and grace, yet possessed supernatural powers that commanded respect and adoration.

Of course the name Thunderbird did not derive until after colonisation whereupon an English translation was put to the creature that was said to carry glowing snakes that were speared into the ground as lightning bolts. Adding to the mythology, the Thunderbird was said to be intelligent, wrathful and powerful, not to be trifled with and generally avoided at all costs.

The Triumph Thunderbird is none of these things, but, it is one very cool motorcycle.

My stepson is constantly amazed when we’re about and about on our bikes. People go out of their way to take a look at the Thunderbird and make all sorts of comments about how nice the bike is. Some recount stories of daring feats committed on Triumphs, whilst others ask if they may photograph the bike. At 19 years of age, James was slightly perplexed by all the attention the old bike gathered. He saw a motorcycle that was difficult to start, is not all that fast, doesn’t particularly corner well, has poor brakes and leaks oil.

She did, and still does, leak oil. Despite what was apparently a fine restoration, the Thunderbird regularly needed some tweaking to keep it in order, not the least of which was the odd dribble of oil. Anyone who has ever owned an old British bike, and a good many folk who haven’t, will testify to their capacity to spill their guts from orifices designed to contain lubricant rather than give it liberty. The Ariel was particularly bad for this. For the first decade of its time with us, the bike stayed in Dad’s shed on the farm. The occasional ride would coat the bike in dust thrown up by the long gravel driveway. Dust and oil are not good bed-fellows, they are in fact the enemy of concourse. Whenever I visited the farm I would usually get straight into some motorcycle maintenance, either with or without the Zen (long story – literally). Maintenance always started with a good degrease to get rid of all the oil and built up gravel dust.

The dirty bird.

Under the dust and grime lived a very nice example of Triumph’s flagship superbike for the fifties. The Thunderbird had been lovingly restored by a member of the Vintage Motorcycle Club in Perth. At the time the bike was restored I was in fact a member of that club but there was over 450 members so I was unable to place him. Sadly, the gentleman who restored the bike never got to fully enjoy it as he passed away soon after completing the restoration, receiving “the big chequered flag in the sky,” as the club used to so eloquently put it whenever they lost a member.

The bike was subsequently acquired by an ex-patriot Englishman who very soon thereafter decided he would migrate back to the Old Country. He loaded all his goods and chattels into a container and shipped it all back to the UK. He then gathered up his family and, similarly, shipped them all off ‘home.’ Evidently things didn’t go as well as expected. Upon arriving in England, the gentleman decided things weren’t that bad in Australia after-all and resolved to return. They actually left the UK before the container arrived, and returned to Perth. It took another two years before the container was turned around and arrived back in Western Australia, whereupon the Thunderbird was removed and promptly sold – to Dad.

I acquired the bike in 2009 when Dad’s hips and knees prevented him from starting and riding it. I rode the bike frequently for another eight years by which time it was starting to look a bit shabby and still leaked oil everywhere. I never did like the silver on silver so, in 2017 I resolved to give the machine a freshen up, a makeover if you like. Like many things that come into my garage, a simple makeover quickly turned into a full nut and bolt restoration.

More about that later, but here’s a sneak preview…

A silver tank and guards on a silver frame didn’t really agree with me so, in 2017, I pulled the bike down to freshen up the engine and re-do all the paint.

The strip-down begins.

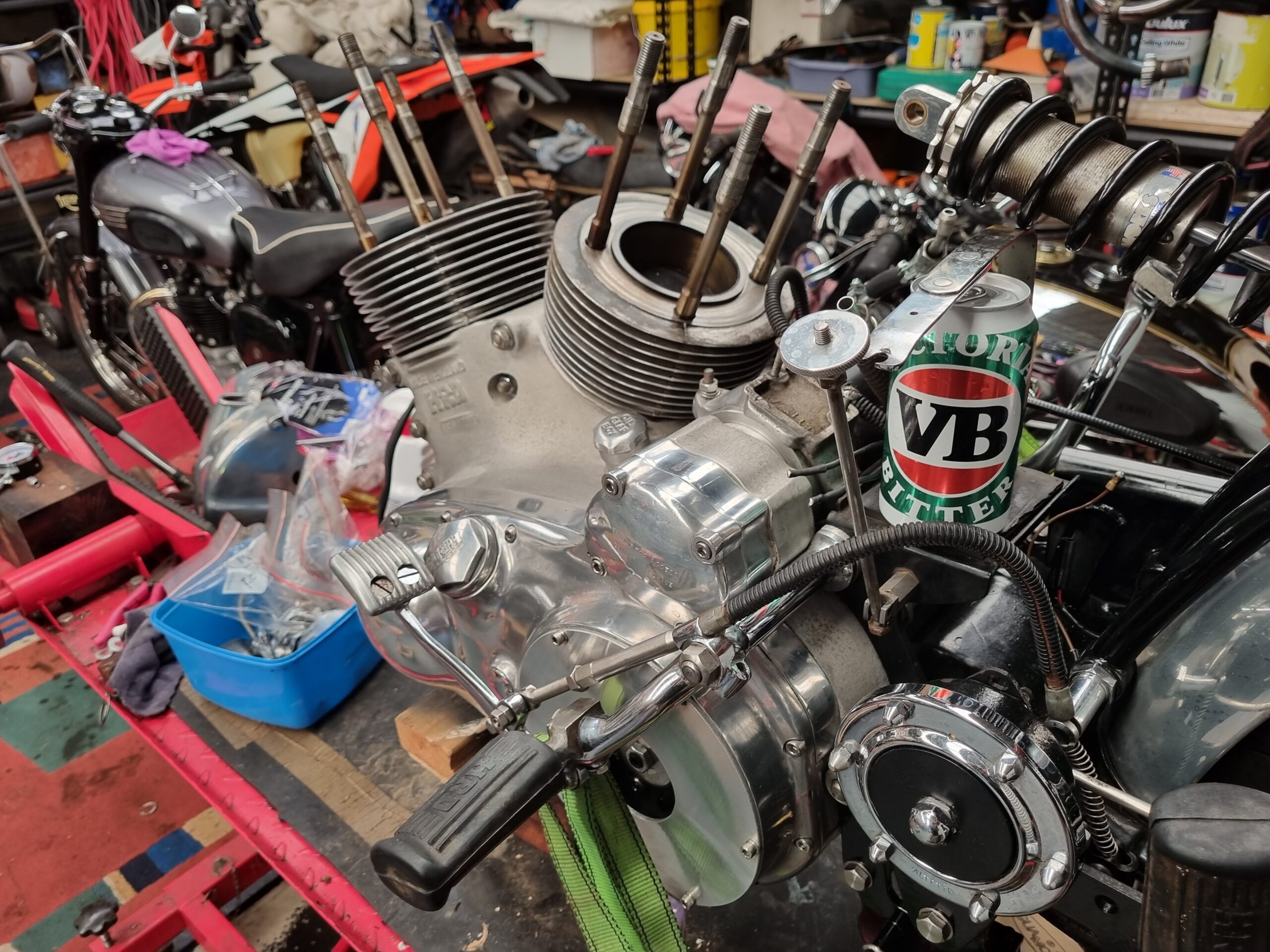

Triumph introduced their 500 cc twin cylinder engine to the world in 1937. In 1949 the Speed Twin engine was punched out to 650 cc and the Thunderbird was born. This is what my Thunderbird engine looked like when stripped to the last nut and bolt.

Parts ready to be sent for a coat of lush, gloss black paint.

This 650 cc parallel twin engine is such an icon it could almost be put on a plinth within the Guggenheim Museum.

The effort starts to pay off when the bike begins to be reassembled.