by Dan Talbot | Feb 21, 2022 | Uncategorized

When we left the Square Four project last month, she was about to be reduced to hundreds of pieces. A lot of those pieces necessitated individual decisions on preservation, restoration or substitution. Preservation is good. I use the term here to simply indicate a clean and polish then set the part aside to be reunited with the motorcycle at some later point. Stainless steel, alloy and brass components come immediately to mind. Restoration is more complex. It includes machining, painting and plating. Substitution is a murky swamp with quicksand just below the surface. Your hand can disappear into this mire with a wad of money, only to come out covered in regret.

Before we go any further, please note, this is not a treatise on motorcycle restoration, it is an informal collection of loose threads that includes some of the highs and lows of such a project. I’m happy to say the lows were kept to a minimum, due in a large part to the previous owner’s deft mechanical skills, for example, the engine was running sweet and strong so there was no point in pulling it apart this time round. But it did look quite grubby so I was compelled to give it a clean-up. I thought I would use baking soda and give it a blast. That’s mistake number one. Mistake number two was attempting to hose it off with water.

My first attempt at soda-blasting didn’t work out so well.

I’m not sure where I picked up the idea to clean the engine with a soda-blast but the end result was a white compound caked into the most inaccessible parts of the machine. I’d made a hideous mess of it. Fortunately, in the back of my mind I knew the bike would be coming apart and having it covered in the dirty white discharge of Frosty the Snowman only served to hasten the pull down.

The pull down on an old British motorcycle can be a messy affair (primarily as they are known to lose a bit of oil) but, remember, grease and oil preserves metal and whilst having your arms covered in black grime is inconvenient, the motorcycle can be remarkably well preserved below the crusty exterior. An acid-bath and cadmium plating will have even the grimiest fasteners looking like new. Better still, you can replace them with stainless steel.

Stainless is an extravagance reserved for the rich or foolish, and I don’t have a great deal of money. There is a lot of hardware at the rear of an Ariel that can be placed by stainless steel. I was introduced to the work of Mr Clay Jones, a UK-based gentleman who owns an Ariel, as did his father before him (sounds familiar). Clay trades under the name of ‘Acme’ stainless steel and writes, “we strongly believe that is not our place to change history and therefore we machine out parts to the correct profile of genuine and original parts we have sourced from and customers over the years” (Acme Stainless). Once you’ve seen Clay’s high-quality pieces fitted to an Ariel it’s hard to contemplate using anything use. Cad-plated steel will not hold the same allure. To this end, I spent and enjoyable evening some 18 months ago loading my virtual shopping cart with an assortment of Clay’s finest machined Ariel parts. I’m happy to say the goods arrived safely in Australia and are now festooned around my motorcycle – it’s the best $1,000 I’ve ever spent on nuts and bolts.

Armour Exhaust and Acme Stainless Steel are two excellent British companies churning out high-quality spares for the motorcycle restoration market.

Some of the stainless steel fasteners I received from Acme in the UK. Beautiful stuff.

Speaking of securing UK hardware, there’s some fine specialist manufacturers at work over there. Armour exhaust delivered a complete four into two exhaust system, manufactured and chromed in the UK, to Australia for less than the price of having the old one re-plated here. The work is first-class and fits perfectly. Unlike a lot of the products coming out of India. Which brings me to the Indian product. Reproduced motorcycle parts out of India is a massive industry.

Recall my previous discussion about reverting to a sprung saddle? The accompaniment to that is a fuel tank from the era. The era was paint and chrome with a large brass cap at the top and an oil-pressure gauge holding court in the middle of the tank. The oil-pressure gauge is a particularly nice touch. It begins to bump up the scale with a few prods of the kick-starter. During times of recalcitrance, I can generally get 50 psi out of half a dozen swings on the kick-starter. Ernie had fitted a Repco-style gauge to the handle bar but the modern instrument looked way out of place. However, having lived with the security of an oil-pressure gauge on a vintage motorcycle I really couldn’t live without one, so I sourced a period-correct, Smiths item from Gumtree. Evidently it was out of an old Jag but it looks perfectly at home on the Ariel. Now, back to the tank.

My Indian-made, chromed and painted fuel tank arrived at my door in rural Western Australia for under $500. It’s a very good piece of work.

I had obtained an earlier Ariel fuel tank but it was too far gone, the swamp swallowed $400. I then took another gamble on an Indian tank. This time it paid off and for less than $500 Mumbai’s finest manufacturing has curried favour with Turner’s creation (there goes another mouthful of the purist’s dark ale, all over their computer screen). The chrome and paint are first class but the tank did leak when fuel was added. An epoxy liner has plugged up the leaks and I now have a gleaming chrome tank, with black inserts and gold pinstripe. The polished brass fuel cap sets things off nicely.

By the nineteen fifties, brass was so last year. It was associated with old vehicles so manufacturers went to great lengths to cover it up, lest their product looked old. These days, when I notice there is brass under rusty chrome, I do a happy dance because I know it’s going to add a golden touch to my machine. Ariel fuel caps are a complicated, three-piece, item that is made of brass and looks splendid when stripped of the chrome.

Stripped of chrome, brass shines like gold.

One of the most important things I do when rebuilding a motorcycle is to upgrade the electrical system. The Ariel was no exception. Elsewhere in my shed, Trispark electronic ignition and a modern BTH magneto reside in my Vincent and Triumph respectively. They provide healthy sparks through iridium plugs and give me great peace of mind. In the case of the Ariel, with its Lucas distributor borrowed from an Austin, I was forced to turn to car mechanics for increased reliability. This included changing my old 6-volt system to 12-volts and sending my aging dynamo to England to have the guts changed out for a 12-volt, 300-watt Nippon Denso alternator. There was no replacement unit. One must retain one’s own unit because, in their wisdom, Ariel put the distributor right through the end of the generator. Anyway, Bennet Longman of Iron Horse Restorations does a marvellous conversion and now I have enough electricity to power a small town.

My Iron Horse alternator conversion in situ. Note the provision for the distributor drive at the right side of the unit.

Bennet asserts a lower kick speed will fire up the engine and, once running, the alternator will balance the charge of the ignition system and modern 12v headlamp bulb at around 25mph. He also bench-tests each unit before it is returned. Back home, during an early test run, and having muddled up the wiring, my kill-switch wouldn’t shut the engine down so I disconnected the battery however the bike continued to idle, powered only by the alternator. I’m guessing it will balance the charge system from the get go.

Another item, which would have been novel in 1954 but not so much these days was the inclusion of an oil filter. I used one that was originally made for a Citroen 2CV. It seems these items are being churned out (again, most likely in India) for use in the motorcycle industry. Back in the eighties I spent some time travelling through Europe with a German in her 2 CV, our lubricant of choice was pilsner (we’ll leave that right there as this is family-friendly forum after all).

The oil-gauge taking centre-stage is a welcome addition to a vintage motorcycle. This one was sourced from an old Jaguar motor car.

Back to mineral oil, and the evolution of the internal combustion engine, Doctor John Ellis, decided crude oil would likely be better at reducing friction than lard, which was the lubricant for most of the 19th century. Dr John was onto something and mineral oil became the saviour of moving parts everywhere. During the early part of the 20th century, dumping oil onto the earth was becoming uncool so engineers started to turn their efforts towards saving and cleaning the engine oil. Oil tanks became a thing and gravity aided in keeping the circulatory system clean with the heavier particles sinking to the bottom.

The oil filter has been borrow from a Citroen 2CV. I’ve tucked it away in the tool box because, after all, who needs tools when you’re riding an Ariel?

Another way of removing contaminants from oil was to centrifugally trap it. Of course, the main centrifuge in an engine is the crankshaft, so early engineers resolved to filter oil in the deepest, hardest to get at part of the engine. To assist mechanics keep these troublesome journals clean, a tube was inserted into the middle of the crankshaft, its sole purpose being to catch particles and grime. These tubes are called sludge traps and they do an excellent job of trapping circulating debris. Eventually, when they’ve caught enough, nothing will get through the journal, oil will cease to flow and the engine will explode, or best case scenario, it will grind to a hault. So here’s a tip. Should you buy an old bike, see if you can find out the state of the sludge trap. My ’56 Thunderbird looked brand new when we got it. Ten years later, I had cause to pull the engine down and a significant amount of sludge was removed from the crankshaft. Disaster averted.

Gunk pulled from the sludge trap in my ’56 Triumph Thunderbird.

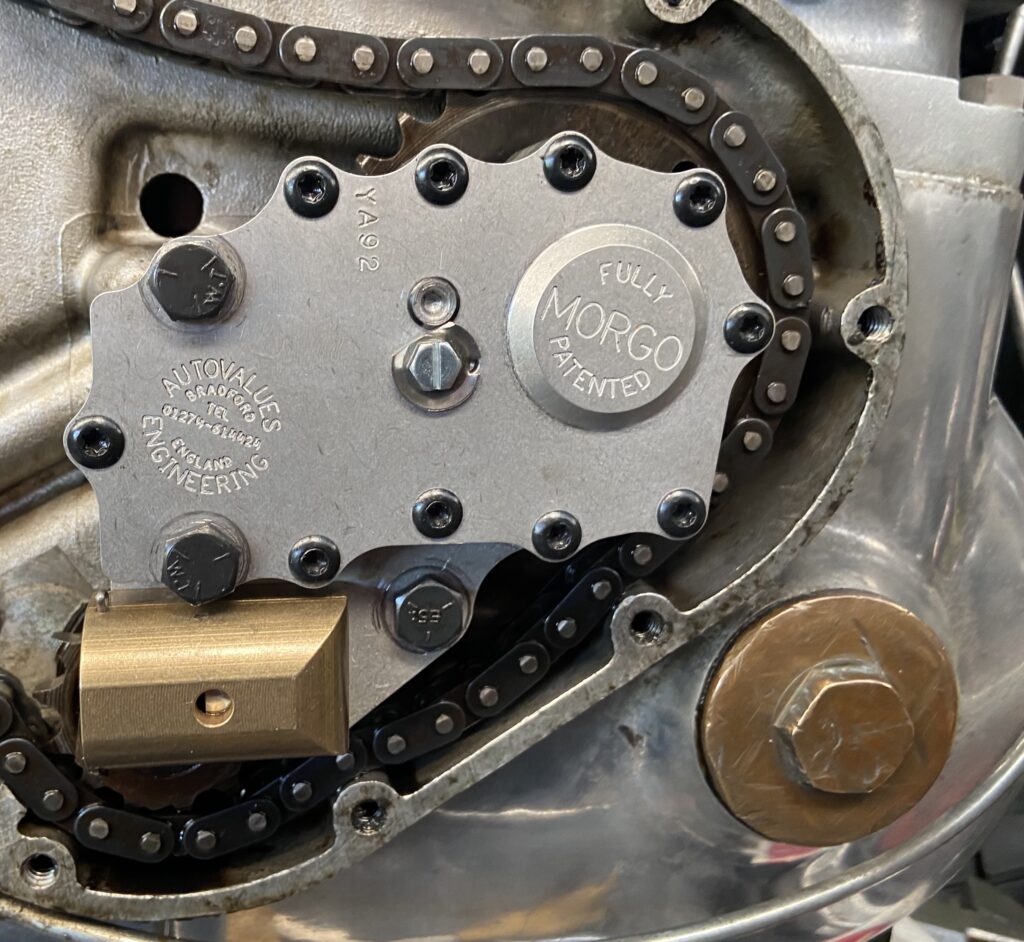

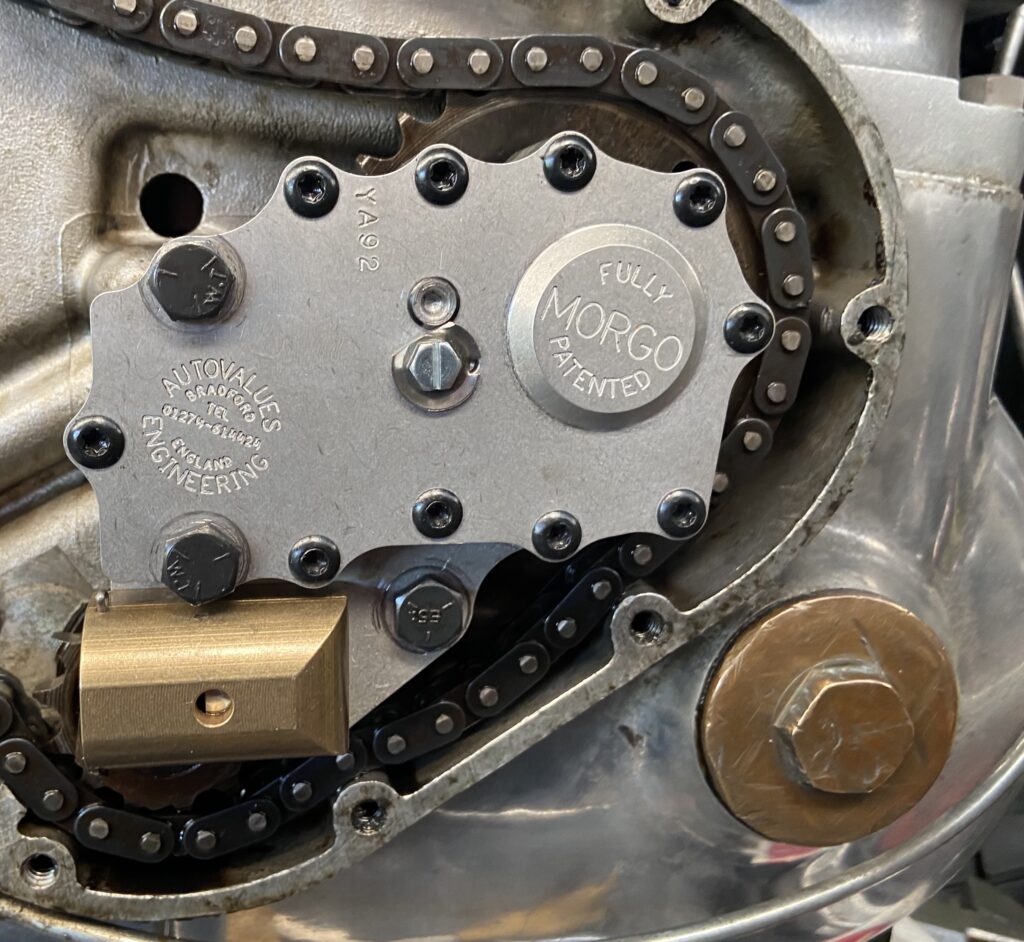

The Ariel remains an unknown but I do trust the previous owner’s judgement and hope there’s not too much gunk in the two cranks. In the meantime, I am hoping my nearly fitted oil filter, a powerful new Morgo oil pump and some good quality detergent oil will help clear the plaque from the arteries of the Square 4 engine. For me, a good oil pump is de-rigueur and the best for British motorcycles is the British made Morgo. In 2019 I visited the factory to pick up one of their big-bore kits for a Triumph and I must say I was very impressed with their outfit. The downside is demand often relieves Morgo of stock and you need to go on a wait list until they do another product run. But it is worth it, a good circulatory system is crucial to the wellbeing of multi-cylinder engines, any engine in fact.

The original Ariel oil pump was removed and replaced with a modern Morgo rotary pump.

The Morgo rotary oil pump is a modern, reliable piece of equipment that has been used in many machines in my shed.

So, there you have it. Everything old is new again. Ariel’s attempt at post-modernism didn’t really work for me (nor did BSA/Triumphs for that matter), so I’ve taken the machine back to its roots. There is another longer story out there about the Ogle-designed Triumph Trident and BSA Rocket 3 of 1969. They were fine machines but, in terms of sales, they flopped. The Americans were having none of it and BSA/Triumph were forced to revert back to the more traditional lines and classic fuel tank in what became colloquially known as ‘export’ models. I’m sure, had Ariel remained liquid, they would have done the same thing. In this case I’ve done it for them, successfully – if I may be so bold.

Now, I must go and sift through my slides for one of a Frau and her quirky little French car.

Aside from stainless steel, regular items look new again with a good coat of cadmium.

Paint, powder-coat, chrome and cadmium. Everything is either painted, polished or plated.

Back home and ready to go back onto the Ariel.

Rewards in stripping off a bit of paint are evident.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 7, 2022 | Projects, Racing

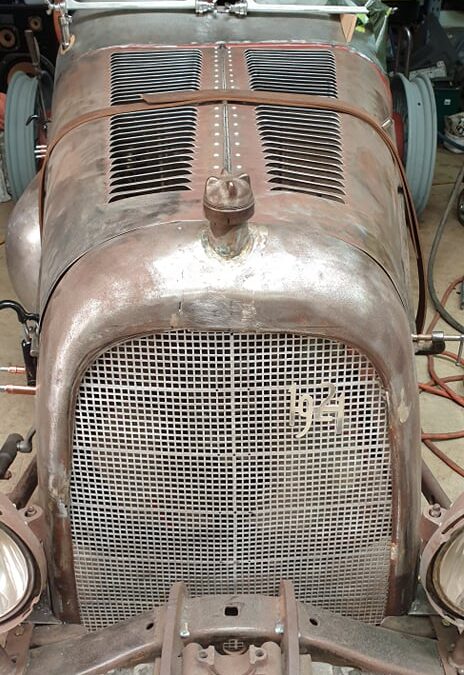

It’s over six months since we introduced Green T to the world. Standing in front of the car this week I couldn’t help but marvel at how Graeme has made the body wide enough for two grown humans whilst, at the same time, expressing an aerodynamic flow that was only beginning to evolve with the race cars of the twenties (that’s the nineteen-twenties by the way, 100 hundred years ago).

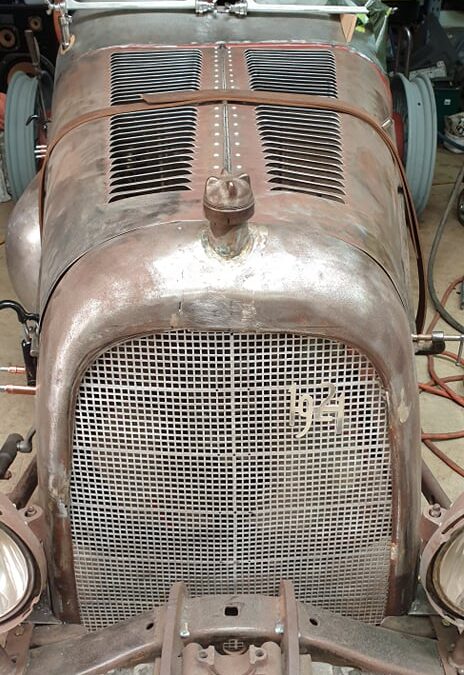

Recall Green T’s body first saw service on a 1922 or 1923 Aston Martin. The chassis on that car was numbered 1927, which is not the actual year of the car. It’s believed to be one of only 11 ‘short-chassis, Aston Martin race cars, which naturally makes it an extremely valuable piece of world motor racing history. That said, the car is believed to have had some four bodies during its lifetime in Australia, the one used by Graeme being removed when it was brought to WA in the early eighties. The original body would have been aluminium and the car has since been returned to such. The steel body, that was removed from the car continues to be molded by Graeme as he grafts it to the 1921 Ford Model T chassis. Graeme has shaped the metal according to his own design, aided along the way with lengths of plastic conduit, cardboard and a healthy dash of creativity.

The bonnet is so long a straight eight could go in there.

Quietly sitting in a corner of Graeme’s shed, the engine sits waiting to be introduced to the chassis. Graeme estimates the rebuilt Canadian four-banger, with its twin Stromberg carbs, extractors and high-performance head, will be pumping out twice the original allocation of horses. It won’t exactly pin the ears back, but we’re quietly confident 130 km/h will not be out of the question. If that sounds slow, remember front brakes weren’t really a thing in the twenties, nor were seat belts or roll-bars so 70 or 80 miles per hour will be plenty-fast enough. Furthermore, we’ll be racing on the slick red dust of Lake Perkolilli so top speed will likely be limited by my in-built sense of self preservation (and a wife punching me in the arm).

The ancient Ford Model T Four-banger has a new lease of life. Note the custom made exhaust system, distributor conversion, and twin Stromberg carbs.

With the body nearing completion, Graeme has begun preparation for the paint. I must say, one could almost seal the raw metal and present the car as she currently stands. The old sheet metal, free of paint and rust gleams like is was rolled just yesterday. In a nod to the famous 1921 Aston Martin GP car “Green Pea,” Green T will be finished in British Racing Green. One can’t imagine any other colour that would be remotely suitable. Not only does British Racing Green look stunning, it has linage in that it is the international motor racing colour of the United Kingdom and has been the livery of Lotus, Cooper, Jaguar and, of course, Aston Martin. It is the Aston Martin hue we are going for.

1921 marked Aston Martin’s entry onto the World Grand Prix circuit with a 1500cc, supercharged, all alloy engine that was lithe and powerful – for the era. Green T, on the other hand, has twice the cubes with a 3 litre, normally aspirated, cast iron engine. In typical American fashion, it pits size and muscle against technical sophistication, and comes off second best. I will, however, challenge any casual observers to pick the multi-million-dollar car from the one created in a shed in Western Australia. Such is the finish of Green T, it looks every bit the racing car it pays homage to.

This early picture of the project shows just how far Green T has come since Graeme first grafted the body onto the Model T chassis.

I would love to fit a supercharger to Green T but, the truth is, such a device would likely snap the crankshaft, which is already the Achille’s heal of warmed up Model T engines. I suggested to Graeme I should perhaps invest in an aftermarket, forged steel, Scat crankshaft. I had a bit of cash hidden away for a rainy day but then it rained cats and dogs. My newly purchased kitten fell ill and consumed the greater part of my rainy-day fund. Any upgraded crank will have to wait until we break this one! Challenge accepted.

Introducing the Aston Martin body to the Ford Model T chassis. Note how incredibly narrow the driver’s compartment is.

This was Graeme’s first go at making the body wider.

Attempt number two, and there we have it, a car wide enough to fit two grown-ups. Subsequent to taking this photograph Graeme has gone to considerable lengths to lift the plenum and shape the mid-section, whilst retaining and even improving upon of the sleek lines of the Aston.

by Dan Talbot | Jan 28, 2022 | Projects

For most of my childhood and my teen years we had an old stockman living on our farm. Bronc, as he was known, was the unofficial sentinel of the sheds and farm equipment, always there to spring me if I tried to sneak the agg-bike out for a bit of one-on-one motocross. No sooner than I had the two stroke Suzuki 185 popping through its spark-arrested exhaust system and that feeling I’m being watched would creep over me. There would be Bronc, hands behind his back, aged Fletcher Jones trousers, worn old boots – without a hint of socks – and a Woodbine hanging off his lower lip. Bronc lived alone with only his cats for company, dozens of cats, he never spent anything of the finer things in life so I assumed Wild Woodbines were a budget cigarette. Everyone I knew smoked Benson & Hedges, Marlborough or Drum. Bronc was the only one I ever knew who smoked Woodbines, thus they became the poor-man’s cigarette, the proclivity of a retired stockman. That was until I learned they were the durry of choice favoured by Edward Turner.

Edward Turner was an engineer and influential designer who was at the dawn of the Golden Age of Motorcycling. He designed single-cylinder engines for Ariel and Triumph before introducing his famous Speed Twin into the world back in 1937. Along the way, Turner also had some other revolutionary designs including overhead camshaft engines that were driven by bevel gears (25 years before Ducati used the same idea). Turner, who has been described as the “most powerful figure in the British motorcycle industry” (Old Bike Australia, 2020), also smoked Wild Woodbines. We know this because the original plans of Turner’s famed Square Four engine were roughed out on the back of an unfolded Wild Woodbines packet. Let that sink in for a moment. One of the most extraordinary motorcycle engines of the twentieth century was scratched out by the designer on the back of a cigarette packet in a London tea-house.

As far as motorcycle engines go, a discussion over which was Turner’s finest piece could only really be settled in the carpark, and that comes from someone who owns both a Triumph parallel twin and a Square Four (recall the scene at the end of Fight Club where Edward Norton’s character is punching on with the imaginary Tyler Durden?). They are two very distinct machines with a common ancestor. Essentially, the Square Four is two parallel twin engines one behind the other, sharing a common crankcase. The drive side of the crankshafts are connected by two massive gears, requiring the cranks to each run in opposite directions. The result is an engine that is torquey, smooth beyond anything else available at the time and a little bit quirky. Certainly, the Ariel would be no match for the Triumph on the race track but for someone who wants to enjoy the sheer pleasure of mid-twentieth century riding the Square Four is hard to beat.

An extraordinary engine, put simply, one 500 cc engine behind the other. This would be the last incarnation of the Square Four engine.

Originally the Square Four was conceived as a 500cc engine, comprising two 250cc engines. The Square Four quickly grew to 600cc ahead of its official 1932 release then a full litre in 1936. It was the original 600cc design, with its chain-driven overhead cam, that gained the engine a reputation for overheating the rear cylinders – a reputation from which the Ariel would never recover. Another thing that would damage the Square Four’s reputation was the fact they were chosen by police forces around the world, including Australia, as patrol bikes. Cops will flog any machine they are given to within an inch of its life (don’t ask me how I know this). Handing any motorcycle to a police officer is akin to submitting it to a long-term endurance race. If the motorcycle is still running six months later it can be considered a success, if not the cops will look elsewhere. Harley tried this (and failed) in WA back in the nineties. WA traffic cops destroyed the Great American Freedom Machine in very short order, but I digress.

If a motorcycle survives police work, it’s okay. If it doesn’t, it never was. Harleys didn’t quite make the grade with WA Police (I can’t imagine why).

This 1949 ex Western Australia Police patrol bike was part of the collection. Note the after market air filter and beefed-up front mudguard designed to support a siren.

Two years ago, I happened upon two Ariel Square Fours, one was an ex-WA Police bike, a survivor. The other was a ’54 civilian model, the last incarnation of the venerable Square Four. Both machines were for sale and when a ride was proffered I took up the opportunity.

It never ceases to amaze me how easily the Square Four starts up (you can see how that test ride ended up). Consider a box of four pistons, fed by a single SU carburetor and ignited by a car-style distributor – all from about 70 years ago. The kick is slow and not exactly easy but at some stage of the second or third swing she will fire up with a unique hum and barely perceptible vibrations running through the machine. The sound is exquisite, not unlike that of a vintage Ferrari or Maserati.

Pretty soon things got out of hand, the Square Four was losing bits and pieces at a rapid rate. Note the single SU carb and Austin A40 distributor.

The steering is surprisingly agile and I’ve yet to scrape anything but that’s only through self-preservation as I have too much invested in paint and chrome to risk sending this ancient machine down the road simply to test its limits.

When I took my newly-purchased machine in for examination, our Chief Machine Examiner, who knows me only too well, said he expected to see it looking like new in the very near future. I indicated I would ride it around for a year or two before doing that however after an early 100km ride I was forced to reassess things.

Elsewhere in my shed I have a ’51 Ariel Red Hunter. The 500cc machine has a plunger frame, similar to the Square Four, just a bit shorter. The Red Hunter also has a sprung saddle, again similar to the early Square Fours. For 1954 Ariel decided they would put a long banana seat, not unlike the one on my Malvern Star Dragster from 1970-something. The banana seat was plonked on the frame, thus eliminating the second tier of suspension, the result being, a ride that was more uncomfortable than the earlier model machines. The rivet-counters wouldn’t like it but, I resolved to revert back to a sprung saddle – and that’s how it started. (To be continued).

My 1951 Ariel Red Hunter 500. Note the sprung saddle and plunger rear suspension.

Close up of the plunger suspension. Both the smaller Red Hunter and it’s 1000 Square Four stable-mate shared this rear suspension. The only thing is, the Square Four lost its sprung saddle.

The Square Four soon after it arrived home.

The idea was to fit a sprung saddle. Then I found a fuel tank …

Next minute.

by Dan Talbot | Jan 8, 2022 | Uncategorized

The Lord’s Motorcycle

By Dan Talbot

For many, the name Hesketh would be quite alien as a motorcycle brand. Certainly, it’s hardly synonymous with motorcycling and I suspect a good many people reading this are not even aware there was such a brand. Hesketh Motorcycles was a company created by Lord Thomas Alexander Fermor-Hesketh, the 3rd Baron Hesketh, and followed his semi-successful Formula One racing team. At a time when the sun was setting on the motorcycle production in the UK, it was Lord Hesketh’s intention to revitalise the industry. His progenitor for this was an audacious 1000cc V-twin sports touring cycle reminiscent of Brough Superior and Vincent.

By the late seventies, the last manufacturer of British motorcycles, Norton Villiers Triumph, was in its death throes with aging designs and sketchy manufacturing practices. The fathers of the industrial revolution were losing the fight against an onslaught of superior machinery out of Japan and Europe. Throughout the seventies I witnessed British motorcycles winning on the race tracks and the streets. When it came time to purchase my first big road-bike it was no contest, it had to be a Triumph. In fact, by that time, if I wanted to ride a new British motorcycle it could only be Triumph or Norton. Many of my friends were riding Honda 750 and Kawasaki 900 machines but they didn’t appeal to me as much as a 750 Triumph Bonneville. To ride a new British motorcycle I was limited to 750 and 850 parallel twins, but, unbeknown to me, plans were afoot in Northamptonshire, England, to re-introduce a British V-twin to the world and re-stablish the Brits as the superpower of luxury motorcycles.

As the kernels of Hesketh Motorcycles began to take hold, some journalists were touting to reintroduction of the Vincent twin. This excited me no end. Regular readers will be aware of my life-long love-affair with the marque and to be able to purchase a new Vincent in 1980 had me ready to sign up. As it transpired, artist’s impressions of what Hesketh might look like bore little resemblance to Vincent and nothing like the machine that was eventually released. At the end of the day, all Hesketh had in common with Vincent was exclusivity and expense, however, unlike Vincents, the Hesketh was plagued with problems.

What’s not to love? A chook’s head as your official logo. Lord Hesketh may have fancied himself as a bit of a Rooster.

The Hesketh was released with a stonking 90-degree V-twin engine. It needed to be substantial as the engine made up the lower part of the frame, in what is commonly referred to as a ‘stressed member.’ At 90 degrees, it looked more like a Ducati than a Vincent or Brough Superior. The engine was a gleaming lump of alloy (destined to devour many a tube of Autosol), part of a handsome machine but one that would not find its way into my heart. By the time the Hesketh was released to the world I had gone down the Harley route and I was firmly entrenched in the American cruiser culture (in my defence, I was young and impressionable. I did however keep an eye on Hesketh, more so out of curiosity than anything else. I was disappointed to learn early examples were beset with problems. We’ll get to the problems – and to how they were fixed – soon. In the meantime, it is useful to review the V-twin engine.

For a long time, British twins were of the parallel variety, where cylinders are placed side by side and fire evenly at 360 degrees in each 720-degree cycle. By placing the cylinders 90 degrees apart, different firing patterns are adopted. A 90-degree v-twin engine will fire at 270 and 450 degrees within the 720-degree cycle. Where the cylinders are arranged 45-degrees apart, the engine will fire at 315 degrees and 395 degrees in 720 degrees. The odd firing patterns of V-twins suggests they run less smoothly than the evenly-spaced, 360-degree parallel twin, which is not so. In the parallel twin, both pistons are rising and falling together, creating reciprocal forces that play out as vibrations through the handle-bars, seat and foot pegs. By contrast, in the 90-degree engine, where the pistons are rising and falling independently of each other, reciprocating forces are lessened. Furthermore, when one piston is firing, the other is travelling at full-speed which tends to balance vibrations rather than create them. Hesketh was wise to employ the 90-degree layout.

Unlike Vincent and Brough Superior, Hesketh emulated the Italians with a 90 degree layout. This engine was salvaged from a machine that was lost in the 2003 National Motorcycle Museum (UK) fire. The engine later found it’s way to Western Australia were it was on display in the York Motorcycle Museum for many years.

Generation one of Hesketh Motorcycles ran from 1980 to 1982. Unable to raise sufficient capital for his creation, Lord Hesketh injected his own funds into the venture but the company ultimately failed. The idiom “creating a small fortune from a large one” played out and by 1982 Hesketh motorcycles fell into receivership with just 139 ‘V1000’ motorcycles being produced.

An early Hesketh V1000. Picture supplied by Mick Broom.

In 1983, with a little help from his friends, Lord Hesketh formed Hesleydon Ltd and had a brief return with another 40 machines, dubbed the Vampire, being produced. By this time, it was well known the motorcycles were afflicted with a variety of problems, not the least of which included; excessive piston clearance (okay ‘slop’), excessively hot rear cylinder and leaky cam-drive case. The marque once again closed its doors. But the story doesn’t end there.

Mick Broom was a development engineer with Hesketh and was intimately acquainted with the engine and the gremlins that lived within it. Furthermore, Mick knew what needed to be done to improve rideability, reliability and longevity of the motorcycles but he was fighting against the winds of a corporate economy that insisted on selling underdeveloped machines, at extraordinary prices, to the public. We’ll let Mick take up the story.

“The obvious question arises, why did a new motorcycle fresh from a factory require all this work after being sold as a up market quality product. The short answer is lack of adequate funding which led to lack of resources and the factory being forced into decisions based on survival with very great pressure from all to deliver bikes. Added to this was the fresh problems due to the different parts and assembly method used at the factory and the ultimate inspector/tester the customer entering the arena and the result was interesting to say the least, for those who lived though it (Broom, 2021).”

As well as a Hesketh engineer, Mick Broom also raced one. This picture comes courtesy of David Sharp and was taken at Silverston in 1987.

After the demise of both Hesketh Motorcycles and Hesleydon Ltd Mick continued to improve the motorcycles with engines being sent to his base in Easton Neston, Northamptonshire. Broom’s improvements were referred to as EN10, a contraction of Easton Neston 1.0. They were, by all accounts a huge success. Writing in the Classic Bike Hub in 2012, Mike Lewis describes the EN10 improved Hesketh as a “Revelation. Gear selection is slick and precise, the meshed cogs remaining silent even at very low revs. A big handful of midrange throttle in top gear brings up 100mph at just 6000rpm.” Lewis goes on to make a clear observation in that without Mick Broom Hesketh would merely be, “at best, a short-lived historical (motorcycle) footnote.”

Mick’s company, Broom Development Engineering, acquired ownership of the Hesketh names and continued with his EN10 modifications. Broom had the capacity to produce up to 12 complete motorcycles a year, although, in his words, “I had the capacity to produce 12 a year but some years I never made one, most of my work was in (EN10) updates.” Mick’s updates included taking delivery of an engine, removed from the host machine and fixing items such as oil regulation, engine breathing, cam chain-case re-engineering, re-machining the bearing mounts within the crankcases. Obviously this is quite an extensive list. In correspondence with the author, Mick said, “One thing you learn very quickly in the development game is that when you have solved ‘ the problem ‘ another will take its place. This chain will only end due to an unrelated, in engineering terms, factor. Very simply our job is to make a mechanical assembly perform better by removing the weakest link, this then exposes the next one and off we go again, usually until the money runs out or we achieve our goal.”

Mick Broom achieved his goal. He has taken just about every early Hesketh and improved the engines to the point they are now reliable, ridable and collectable motorcycles. Mick sold his stake in the company in 2010 and since then Paul Sleeman has built a very limited number of large-capacity V-twin motorcycles carrying a 1920cc S&S engine. That is a story for another time. Since then Paul Sleeman has built a very limited number of large-capacity V-twin motorcycles carrying a 1920cc S&S engine. That is a story for another time.

Two prototypes. 1979 V1000 and 2005 V1200 Vulcan at Eason Neston, Towcester 2005. Photograph supplied by David Sharp.

2005, V1200 prototype – if only …. Photograph supplied by David Sharp.

Hesketh Owners Club meet at Easton Neston Hesketh works 2005. Mick Broom is next to black V1000 WKL982X. Photograph supplied by David Sharp.

Hesketh Owner’s Club meeting. Obviously these motorcycles have remained popular with owners. Photograph supplied by Mick Broom.

This Hesketh was photographed in Victoria in the eighties by Bob Fursdon. Word has it this machine is still ridden regularly in the Central Coast, NSW.

Special Thanks to Mick Broom and David Sharp for their assistance with this piece. Also Bob Fursdon who piqued my interest in Hesketh all over again when he showed me the above photograph.

Post script (below), this is the latest incarnation of Hesketh. The motorcycle, powered by a 1920cc S&S engine, has been produced by Paul Sleeman in the UK. Dubbed the ’24,’ Sleeman intends on producing only 24 of these machines as homage to the late James Hunt. 24 was Hunt’s number with the Hesketh Formula 1 Racing Team. At this time, only a handful of machines have been produced.

by Dan Talbot | Nov 3, 2021 | Collection

Every time I put my foot down hard at under 40 mph in this muscled Mustang, it sounded like ten vestal virgins being raped simultaneously. Actually it was only the tyres (Bryan Hanrahan, Modern Motor, 1966).

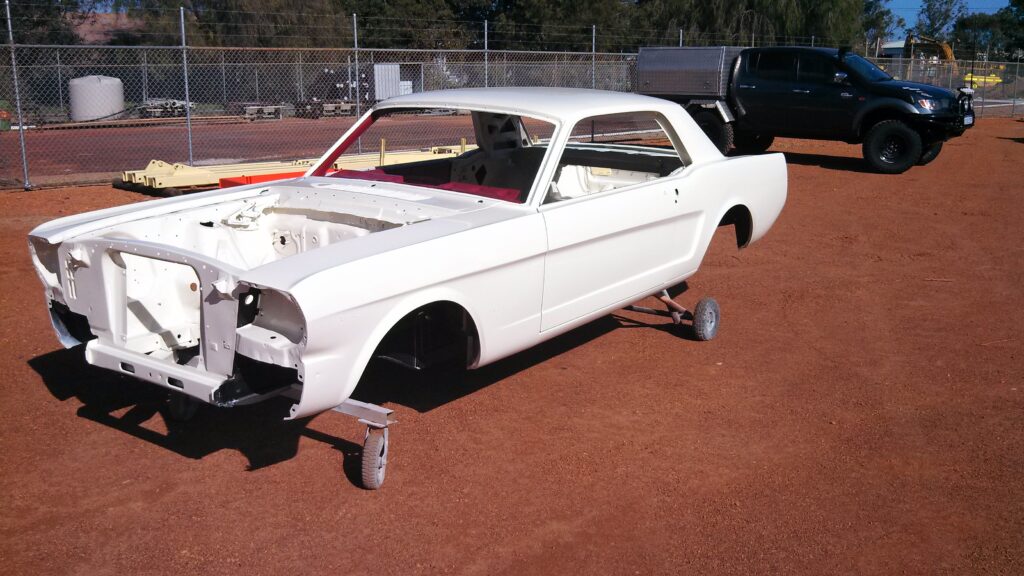

The things you could say in 1966! We’ll get back to Bryan later, for now the Mustang has taken another great leap: we’re on the road. The car has passed engineering with WA Department of Transport (DoT) approval for a modified “high performance” engine, rack and pinion steering, coil-over suspension, improved brakes et al. In other words, she’s totally legal and licensed to thrill.

Aside from the restoration, dealing with and meeting the expectations of the DoT has been tiresome. At the end of this piece is a list of the requirements I had to meet before the car would be considered roadworthy. It should be noted, all of this was because I fitted improved braking, steering and suspension. The components I used had been previously been engineered and deemed compliant with Australian Vehicle Standards Rules. A gazetted engineer had to examine and sign off on all the items on the list. He spent the best part of a full day with me and the car, which included taking it to a workshop equipped with a dynometer to ensure I wasn’t producing too much horsepower. Had I rebuilt and licensed the car in its original form, none of this would be required.

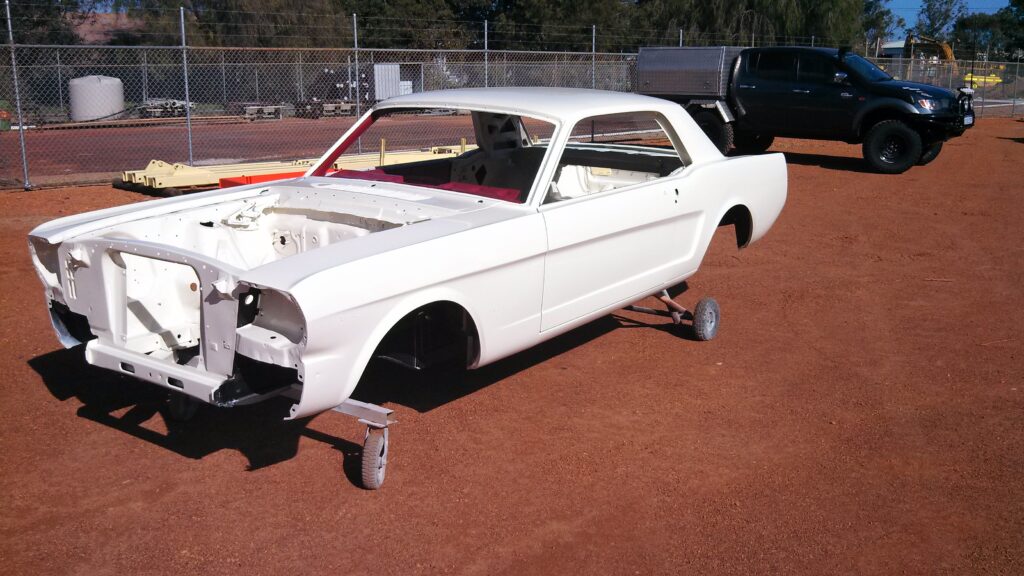

The DoT movement permit has a provision for a number plate. I used “THESEUS.” The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that raises the question of whether an object that has had all of its components replaced remains fundamentally the same object. Such was the state of the original body, everything in this photograph, save the roof, has been replaced.

What started as a transmission rebuild eight years ago grew to a full nut and bolt, rotisserie restoration. Every skerrick of paint and filler was blasted away revealing a very sorry sight, but that’s all history now and the scars of financial pain have diminished. What I ended up with was essentially a brand-new body, with more than half the panels replaced.

The modifications I have carried out on my car probably put it into the ‘restomod’ category of rebuilds. I’m not all that comfortable with the term ‘restomod.’ It’s a contraction of restoration and modification and came out of America where the modifications I’ve made are more readily accepted. In my case it is probably an apt description but I prefer to say ‘make it your own.’ That’s what I’ve done, I wanted to retain the original feel of the Mustang whilst making it safer and more pleasant to drive, and I believe I’ve achieved that. The car tracks beautifully and gives me great satisfaction knowing I’m (kind of) responsible for that.

Recall from the early days, when I said, “One of the defining features of Falcons of the sixties and seventies is the feel of the steering. It was much better than the equivalent offered by Holden and Chrysler but my Mustang was simply awful to steer. Added to this, the transmission was slack and spongy. The car was very much a disappointment.” Well not anymore. One of the reasons the car handled so poorly was the thoroughly agricultural conversion carried out by Ford Australia (Homebush story) way back in 1966. In his 1966 review of the Mustang, Bryan Hanrahan said, “I liked the Mustang. It made me feel ten years younger when I first drove it: it took ten years off my life the first time I tried to corner it hard.” Ironically, original Australian-converted Mustangs, of which there was only about 200, remain the most collectable in unmodified form. But not for me. I wanted something to drive and I was not prepared to live with vague steering and poor braking (fear not, I have saved all of the OEM parts).

RRS steering rack, no longer is the steering vague.

Upgraded brakes provide reassurance.

The DoT insisted I put the car on a dynometer to prove I was not making more than 20% power over normal (it cost me a new camshaft but that’s another story).

By the time I got the rubber to the road, I had an RRS manual steering rack, RRS coil-over front suspension, RRS front strut bracing and RRS disc brakes. The front and read subframes had been connected using aftermarket chassis rails produced for the purpose. I also increased the size of the sway bar from the standard 20mm to the larger 25mm. I may have made a mistake with the manual rack but, that aside, once on the move it feels responsive and reassuring. I did however make a major misstep with the engine.

When I noticed a later (1985) roller-cam 5.0L engine pop up on the market I purchased it, as opposed to rebuilding the original 289. My engine guy built a very strong engine but when I declared the swap to the DoT, they started throwing around the term ‘high performance,’ and that’s when the fight started. The 5.0L engines were released with fuel injection and found their way into a variety of cars, including the Falcon GT. My car had no fuel injection and produced nowhere near the same power as the GT but the DoT err on the upper side of caution and if one variant produces x horsepower, then they all do! It was, for all intents and purposes a fairly standard Ford Windsor V8 engine commensurate with the era. My misstep was using an engine block from 1985, instead of one from the sixties, notwithstanding they were identical. I launched an appeal to DoT and got into a long stoush about the performance capabilities of my engine. Some of which is repeated here;

During the restoration, I learned of a 302 engine for sale in Perth that would negate the need for a complete rebuild to the extent I faced with the existing 289. The 302 engine, whilst still in the Windsor family of engines, proved to be one of the later model, “5.0 litre” blocks which had previously been fitted with fuel-injected. The engine was sold to me as having been ‘refurbished’ in the USA. It was always my intention to use only the short block with the, distributor, starter-motor, carburettor etc from the original car. As it transpired, the 302 required a full rebuild, the corollary being an engine that cost more than rebuilding the original 289 would have been but, by the time I learned that, I was deep into the rebuild and kept going. The car has undergone a preliminary examination by a DoT gazetted engineer. During the examination the engineer said a dynameter report would be required to show the transposed engine was not creating more than 20% of the original power output. The resultant report proved this to be the case.

I had a win but the whole argument was pointless. The dyno report proved the engine did not belong in the high-performance (LA2) category of engines that should have been the end of it. I had to fight the decision as the list of safety upgrades required for the later engine (see below) was completely unreasonable and, in some of the items, unachievable. As I said above, the car had been through engineering and found to be properly constructed, safe and compliant with Australian Design Rules of the era. What I was fighting was the unreasonable assertion my engine was ‘high-performance’ was therefore elevated the car into some unachievable level of finish. I had some very good people in my corner, Graham Billington for one. Had I lost the fight, I would have been consigned to refitting the 289 and running it through licensing with that engine (and possibly even having to revert back to the original steering, brakes and suspension). In hindsight, I should have rebuilt the 289 in the first place. It would have saved so much grief.

Looks like a Windsor duck, walks like a Windsor duck, quacks like a Windsor duck. Must be a Windsor. The Dept of Transport agreed however they also deemed this engine ‘high-perfomance.’ Of course, it was no such thing. Swept volume and dynmeter testing proved as much. Note also the RRS bracing which also had to have engineering approval.

This picture shows the sub-frame connectors being set in place. These pieces link the front and rear sub-frames and give the car extra rigidity.

August 2016. During the refit process, a professional photographer came into my shed and took a few pics. This remains one of my favourites. Thankyou Graham Hay.

Even after the car had been through engineering, it still had to be trailered to Perth for examination. I entered into another long, drawn out battle with the DoT over being able to have my car examined locally. I lost that fight.

On a final note. All of the OEM items remain under my bench with the engine. All the steering, suspension, brakes and braces have been retained for posterity. The hammer-blows of the people carrying out the conversion remain on the shock-tower and chassis rail, as does the quirky, left-hand wiper swipe and the forward-mounted brake booster. If a future owner wants to return the car to the form in which it left the Ford Australia Homebush facility, he or she will be able to do so. In the meantime, I’ll be out there putting the old girl through her paces (as they said in 1966).

The following is a list of requirements I had to meet to allow the car to pass examination;

The Consulting Engineer or Signatory report is to address the following items:

- Consultant to confirm the correct engine number as stamped on the engine block by the manufacture.

- Due to the engine fitment a Mandatory Upgrade of Safety Equipment will be required to include:

- Seatbelts to be installed to all seating positions – retractable lap sash to outer seating positions and lap seat belts to centre seating position.

- Split or dual braking system.

- Windscreen washers.

- Two speed windscreen wipers.

- A windscreen demister.

- Flashing direction indicator lights must be fitted at the front and rear of the vehicle.

- A collapsible steering column must be fitted.

- Fitment and suitability of the (year to be supplied) Ford 5.0-litre V8 naturally aspirated petrol engine in regard to complying with Section LA2 of VSB 14.

- Confirmation of the swept volume of the engine is required. Swept volume test to be sighted by the signatory and results including bore and stroke dimensions to be supplied.

- Fitment and suitability of any modifications to the engine including camshaft, fuel injectors, throttle body, air intake and any ECU programming complying with Section LA4.

- Signatory to provide evidence and engine specifications at time of test to certify that the maximum engine power does not exceed the 180 Kw per tonne power to weight ratio based on the heaviest variant of a 1966 Ford Mustang Sedan.

- A Dynamometer report on the maximum power and torque produced at the wheels after modification is to be supplied. The report must include VIN, engine number, maximum power and torque to be signed and supplied by Consulting Engineer or Signatory to prove compliance. Note: The report must list maximum torque and power on the Y- axis and engine rpm on the X-axis.

- Special consideration should be given to the extra weight applied to the front axle to ensure the manufacturers load capacity is not exceeded.

- The modifications to the exhaust system must comply with Section LA including LT4 (Noise Test) of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the Ford C4 automatic transmission complying with Section LB1 of VSB 14.

- Verification that the speedometer has been tested (and recalibrated if necessary) to the applicable ADR or where no ADR is applicable an accuracy of +10% or – 0.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the body/chassis modifications including engine and transmission mounting and fitment complying with Section LH of VSB 14.

- The total body/chassis structure and driveline being capable to sustain all of the stresses that is likely to be experienced by all of the proposed modifications.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the right-hand drive steering conversion complying with Section LS1 and LS2 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the RRS Rack and Pinion Steering conversion complying with Section LS4 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the modified suspension complying with Section LS of VSB 14.

- Evidence is required to verify the suspension travel is not reduced by more than one third of the manufacturer’s specifications.

- Special consideration should be given to ensure regulated height and ground clearance requirements are met.

- The consultant’s report is to supply the OEM and modified eyebrow and roof height dimensions.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the body/chassis modifications including chassis strengthening complying with Section LH of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the modified braking system (if other than total OEM option) complying with Section LG1 & LG2 of VSB 14.

- A brake test will be required for this vehicle as per LG1 Design Approval, refer to Table LG4 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the wheel track, wheels and tyres complying with Section LS of VSB 14.

- The wheels and tyres specified in your application appear not to comply with the LS section of VSB14 (overall width & diameter) and therefore are unacceptable. The LS section of the code fully explains the requirements. It is suggested that VSB14 be referred to and consultation with an Engineer to select wheels and tyres that meets the requirements of VSB14.

- A weighbridge docket verifying the vehicle TARE weight is required.

- The total body/chassis structure and driveline being capable to sustain all of the stresses that is likely to be experienced by all of the proposed modifications.

- Any other test or report that the consultant may consider necessary to prove conformity and safety of the modifications.

Please Note: Any modifications that are performed to the vehicle, additional to the original application will require a complete, new modification application to be submitted for re assessment. 5 of 6 Vehicle Safety and Standards 34 Gillam Drive Kelmscott 6111 Telephone (08) 92168579. Email: tps@transport.wa.gov.au

Note: This letter and the copy of your application are to be shown to your Consulting Engineer or Signatory, so he is aware of the items to be addressed.

Consulting Engineer or Signatory report is required to coincide with the application submitted by owner or agent. Time delays will be incurred, and the possibility of a new application will be required for the modifications by the owner or agent.

- Approval in principle to modify is granted at this point; however final acceptance cannot be completed until an acceptable report is submitted to DoT, Vehicle Safety and Standards Section for assessment and approval.

- This approval in principle for modification of the vehicle is valid for two years from the date of this letter; the Technical Policy and Services Coordinator must approve any further extension of time in writing.

- The report must include the name and address details of the applicant, vehicle details e.g. Make and Model, Year, engine, transmission, vehicle identification number, engine number and the Vehicle.

Special thanks must go to Graham Billington of Ultimate Automotive in Bunbury who came to the rescue when, having received the above letter, I tossed my toys out of the cot and and threatened to sell the finished car – unlicensed. Graham called me and, through the art of gentle persuasion, made me realise I had come too far to give up. I’m glad I persevered, thanks Graham. Now I’m off to find ten vestal virgins.

The car is registered on the WA Concessions for Classics (C4C) licensing scheme. This is much less restrictive than the former (404) scheme and allows us to use the car for special treats – such as a date night at a local restaurant.