by Dan Talbot | Mar 12, 2021 | Collection, Projects

Forgive me readers of the ‘Shed for I have been a bit slack of late. It has been some months since I last put my pen to paper, so to speak. In my defence, I have been a wee bit busy writing a 100,000-word thesis which is now with examiners in the UK. So obscure was my topic, we couldn’t find people qualified enough in Australia to pass judgement on my doctoral scratchings. Anyway, back to the shed.

There has been a bit on, the most significant being we have a new inclusion to the ‘Shed. On Christmas Eve, we picked up a 1938 Chevrolet half-ton truck. In trucks terms, it’s very small, more like a flat-bed ute. It is licensed and running, but needs some serious work. The little truck was built in Australia from an engine/chassis imported from Chevrolet USA and built up according to Australian demands, which, at the time were many. Clearly, however, power wasn’t one of them. Driving the little truck 60 kilometres to home was laborious. She was flat out doing 40 miles per hour and for a time, I became more of a nuisance than the mortal enemy of motoring enthusiasts everywhere – the caravan.

The Chevy has been purchased by Catherine for her honey business and will become both a practical and promotional vehicle for Wedderburn Honey. Affectionately known as “Honeycomb,” the first order of business is restoring the bodywork, followed by giving her longer legs (the truck, not my wife). Both of these undertakings are easier said than done.

In terms of the first undertaking, as I write, all the tin-wear is off the chassis and is with the painter. The guards have been finished and the running boards are almost done. The cab is a bit trickier but for a truck of some 82 years of age, it’s in remarkably good condition. I trust the photographs accompanying this story will add credence to my assertion. Some folk will look at the photos and quickly start bleating about patina and leaving it as it is, and so on. Let me stop you right there. My wife and I are of the opinion ‘patina’ is a euphemism for being too lazy to go to the trouble of panel and painting. Aside from this, the so-called patina in the photographs is not original. Unearthing body panels revealed the original colour, an olive gold, and it is to this we hail. Giving the car some beans is equally fraught with complexity.

At a time where every man and his hound are putting V-eights into classic Chevs, we are breaking with tradition and sticking with the straight six, or “Stovebolt” as they are affectionately known. The original, 1929 Chevy sixes were held together with bolts that apparently looked like they had been lifted from wood-burning stoves, hence the name. Stove bolts have long since been dispensed with, but the name has stuck with the venerable donk and now there is a renaissance of the humble Stovebolt taking place across the USA which, one would expect, will arrive here in due course. And we’re ahead of the play because we’ll be running a stonking big Stovie. A 292 in fact. The 292 cubic inch engine will be coupled with a Muncie four speed truck box – Catherine insisted on a truckie’s manual gearbox and it is her truck. Behind the gearbox will be an Aussie Holden, one-tonner diff with a 3:1 ratio.

Whilst we’re on Holden. Our truck originally arrived in this country in February 1938 as a knocked down, Chevy engine and chassis. In the decades preceding the Great Depression, the craftsmen and women of Holden body works had earlier busied themselves with making saddles before progressing on to motorcycle sidecars. In true ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ Holden turned to automobile bodies during World War One and emerged with a workforce skilled in auto body construction. The rest is, as they say, ‘history.’ We possess a little piece of that history and here it is.

Be sure to check in on our Facebook page, Honeycomb the Truck, for more frequent updates on the progress of our restoration https://www.facebook.com/Honeycomb38Chev

The interior of our ’38 truck. Basic, bare and beautiful.

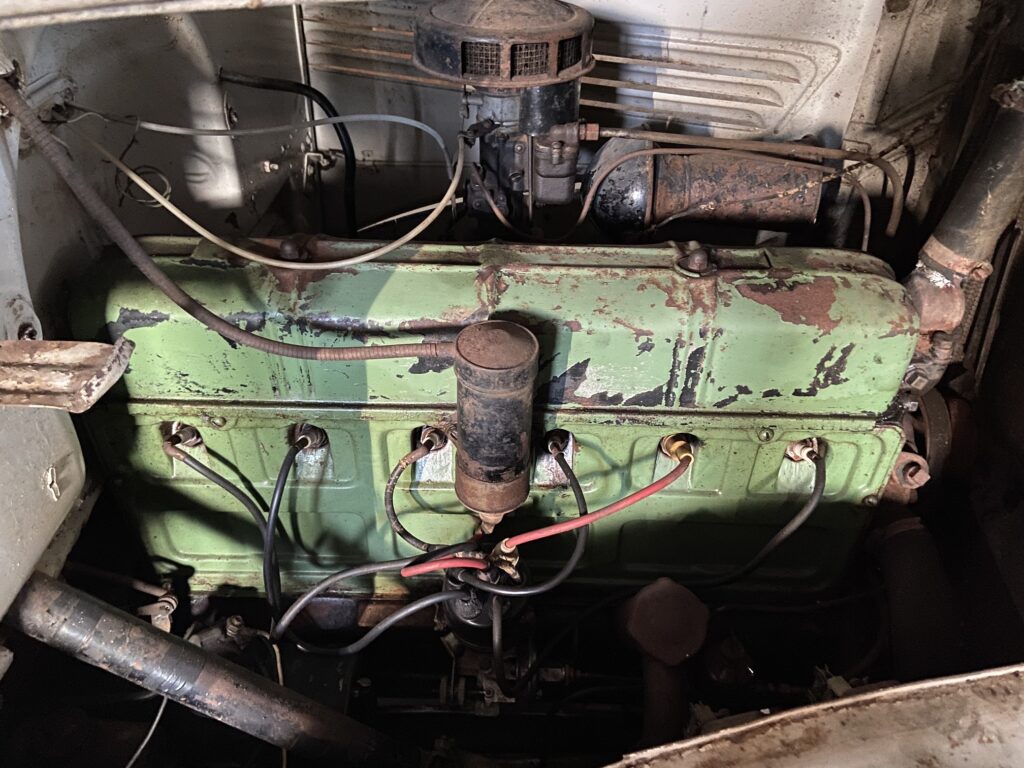

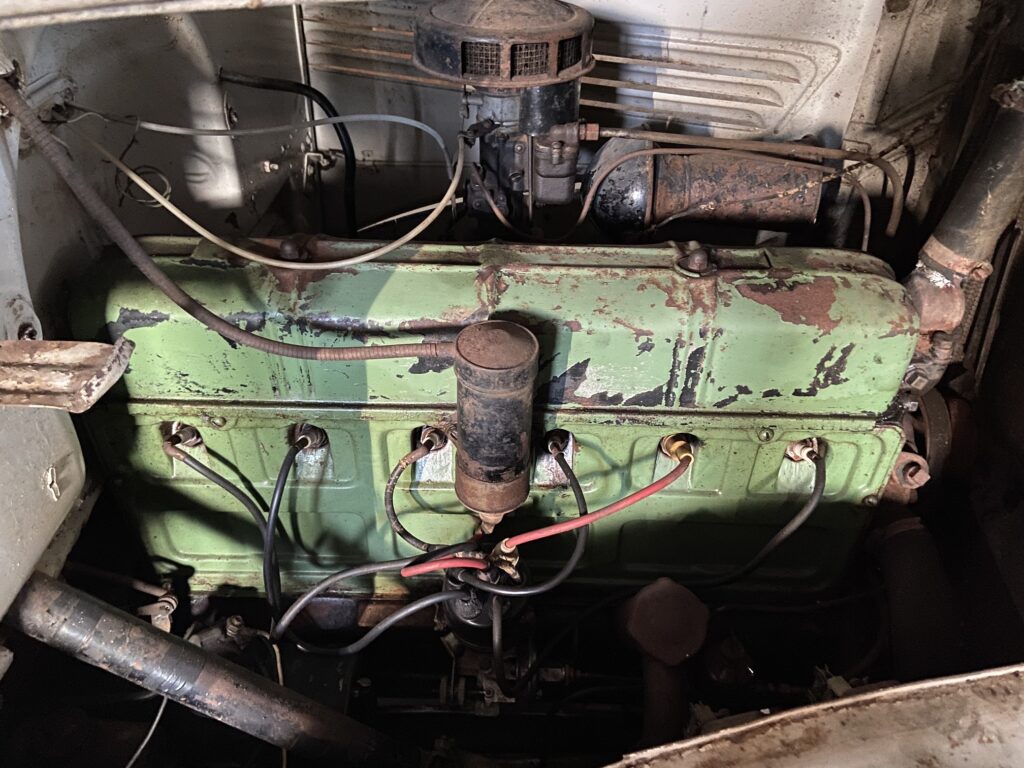

The venerable Chevy Stovebolt six. This one will be replaced with an engine that will propel us down the highway at the same speed as the rest of the traffic.

Body by Holden.

Unmistakably Chevy. The ’38 still bears the plates of its former home, Kulin, in the Western Australia Wheatbelt.

We would like to think the timber that makes up the buckboard rear of Honeycomb is original. We plan on re-using as much of it as we can.

Disassembly of the little Chevy truck commenced within weeks of her arriving at our home. Note the shades of the original olive gold beginning to emerge, having been hidden since the last re-paint.

Catherine finds a nice place to hide.

Word from our body and pain man filtered back home “Keep Dan away from that gas-axe.” Evidently I was burning away more than just rusty old bolts.

As we whittled away various body parts, the value of a life spent in the wheatbelt become apparent. Rust was minimal of an 82 year old lady.

By 1938 brass was so last year. The world was turning onto chrome plating and beautiful brass was being hidden. Not any longer. We have revealed quite a few brass pieces that have been covered by pain or chrome. They will be polished and displayed in all their original glory. This hubcap is an example.

A sneak preview of things to come. Some pieces have already begun to filter home.

Still in the Stovebolt family this larger engine will give the little Chevy the long legs she needs.

by Dan Talbot | Nov 9, 2020 | Events

The Albany Vintage and Classic Motorcycle Club have staged another fabulous event.

When my wife began looking for a classic motorcycle to replace her SR 500 Yamaha she had a couple of criteria. It had to be eligible for classic hill climb competition and, importantly, it had to have an electric start. The SR was fine in the former category but with no electric leg it proved to be difficult for her to start so we ended up moving it on and purchasing her a 1987 GB 500 Honda. This machine uses the XR engine so it’s virtually indestructible and it starts at the press of a button. Catherine was all set, except the first event was destined to rain on her parade, both literally and metaphorically.

The little GB 500 is a tidy machine and starts at the press of a button, but, sadly, too new to compete in the Albany Hill Climb.

When it came time to fill in the entry form for the Albany Vintage Motorcycle Hill Climb, it became apparent the cut-off was 1980. Anything made after that year was out. Being made in ’79 the little SR would have been allowed, indeed, we had entered it in 2019, but the Honda was definitely excluded. With the SR off enjoying life with a new owner, I suggested Catherine compete on the Thunderbird. It was not entirely alien to her, she had ridden the bike and was, by all accounts, competent on the strikingly beautiful motorcycle. She wasn’t happy but agreed I should fill in the application with her on the ‘Bird.

Catherine happy at last to be on our strikingly beautiful Triumph Thunderbird.

2019 had not been a good year for us at the Albany Hillclimb. We couldn’t get the SR to run properly so it was loaded onto the trailer without firing a shot in anger. I on the other hand, did get a run at the hill. I was on my Triumph Triton which has a one down/three up gear-change patter. The Vincent, on which I had been spending most of my time lading up to the event, is one up/three down. On the first go up the hill on the Triton, instead of changing up (like a Triumph should), I changed down – like a Vincent does. The result was a destroyed gearbox.

The gearbox in the Triton required a full rebuild thanks to some errant shifting on my behalf in the 2019 event.

Back to this year. By the time the hill climb weekend came around, Catherine hadn’t even sat on the Thunderbird and it had been perhaps two years since she had ridden it. She had barely ridden her ‘new’ Honda but she assured me she would get some practise on the hill at Albany the day before the event. We drove the 400 kilometres to Albany in beautiful, warm weather and arrived in the seaside town on the Western Australia South coast in the late afternoon. We unloaded the Thunderbird and the Vincent and started them briefly before making them secure for the night (I do this with a few reassuring words).

We were staying at Middleton Beach, near the base of hill climb circuit, so on Saturday morning I opted to take Catherine up the hill on the way to the show and shine event in the Albany CBD. I took off up the hill like a scalded cat and pulled in at the top to wait for the wife. And waited … and waited. Eventually she came puttering up the hill at a snail pace. The Thunderbird was clearly a bit crook but we made it into town. Getting off the Triumph Catherine said, ‘this thing handles like a bag of spuds.’ Make of that what you will but, sure, it’s not as svelte and tight as the little GB which it gave 30-something years away to, but at least by that time the engine was running a bit better. It may have been stale fuel or a blockage but after I topped the tank up with some clean, new petrol the ‘Bird ran sweet. The Thunderbird really has a lovely engine. Everything else in the shed seems angry by comparison.

After a couple of hours Catherine was completely at ease with competing on the Thunderbird. Here she gets some reassuring words of wisdom from WA and UK speedway Ace Rod Chessell. Photo by John McKinnon.

By the end of Saturday morning, having received so many compliments for her choice of machine, Catherine was beginning to feel quite chuffed about being on the Triumph. Granted, I had to kick it every time she needed to get the engine running and, granted, the brakes are merely suggestions for washing off speed, but Catherine soon reacquainted herself with the bike and even managed to get it up the hill in a reasonable time. After the practise runs, and satisfied she knew what she was doing, Catherine and I retired to a bar from which I could drink beer and feast my eyes on two of the most handsome machines in all of motorcycledom. All in all, our Saturday was most enjoyable. The Vincent, the Triumph, the wife and I were in Albany – and we meant business. That night it rained.

Our first couple of runs on the hill were on a wet track, however, by mid-morning the roads were dry and our speeds lifted – which doesn’t help where you’re running for consistency.

I woke at 4.00 am with the rain tumbling down and lay there listening to it as night gave way to a murky, grey loom. This is not surprising. In the local, Nyungar, dialect, Albany means ‘Place of Rain.’ Tourist brouchures promote the area as the “Rainbow Coast” and with an average of 177 rainy days per year we didn’t stand a chance. We trundled off down wet streets spraying my hitherto gleaming alloy engines with a fine mist of pure rain-water and road grime. I was feeling pretty glum as I was sure the event would be cancelled, but no, we would ride: rain, hail or shine. Gentlemen, start your engines. And, in my case, start your wife’s engine too.

We had two runs up the hill to set what would be our nominated time. The aim of the event was then to do three runs up the hill all at the same speed as the elected time, with points lost for going over or under the nominated time. Catherine picked 76 seconds and I picked 48 seconds. Our two dial-in runs were made on wet roads but by the time we lined up for our timed runs, the rain had stopped and the roads were drying out.

The Albany Vintage Motorcycle Club go to great lengths to host their signature hillclimb event. Injuries, crashing and irresponsible behaviour would jeopardise the future running of the event so it came as some relief as the weather turned for the best. It also meant I could give my 1000 cc v-twin a bit more of a handful going up the hill.

To say the Vinnie is loud would be an understatement. Being lined up together was both comforting and burdensome for my wife. She knew she had nothing to prove but she wanted to get away cleanly. The only way should could do this was to allow a second or for me to get away and so she could hear the tone of the Triumph and set about getting it off the line, which she did quite nicely on all three runs, pegging the little 650 to the stop in the first couple of gears she managed to come within .6 of a second on all three runs, however, they were all three seconds below her nominated time. My spread was over 2.5 seconds and two below my nominated time, so I was well out of the running. That said, I had a blast taking the big twin by the hill at full tilt. Best of all, no motorcycles were harmed in the making of these times.

This young man was obviously taken with the stunning beauty of the Vincent Black Shadow.

They don’t call him “Rocket Rod” for nothing. Rod Chessell powers from the line on the JAP special alongside his former speedway adversary Bob O’Leary. Two legends of the sport. Photo by John McKinnon.

Bob Wittingstall’s stunning 1913 Sears on display at the Show and Shine, being guarded by his friend Kelvin.

Not quite the Battle of the Little Bighorn but Indians were prominent at Saturday’s Show and Shine and in the hill climb on Sunday.

Brian Cartwright on his ’53 Vincent sidecar.

Murray with his 1950 pre-unit Triumph outfit. Photo by John McKinnon.

Bob Rees was back in the saddle after suffering a motorcycle crash in Africa last year that left him with critical injuries. Photo by John McKinnon.

Will Turnbull on his 1960 Triumph Bonneville lines up against Tom Constant, AKA the Toad, riding the ’71 Moto Morini 125.

Bob Wittingstall with his Brough Superior SS80.

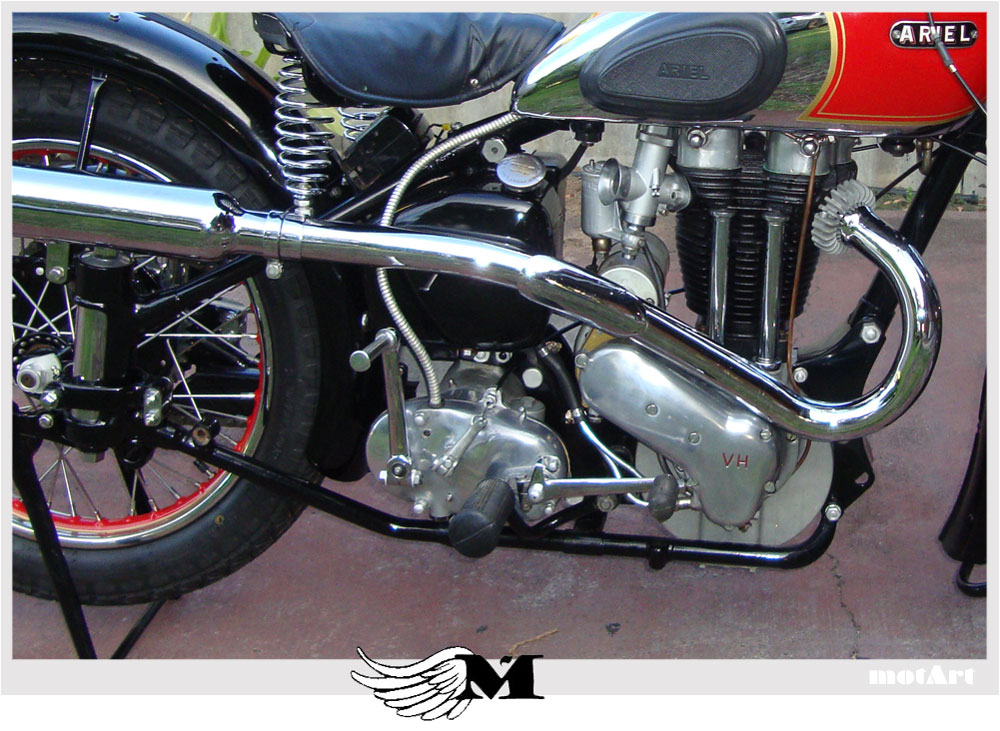

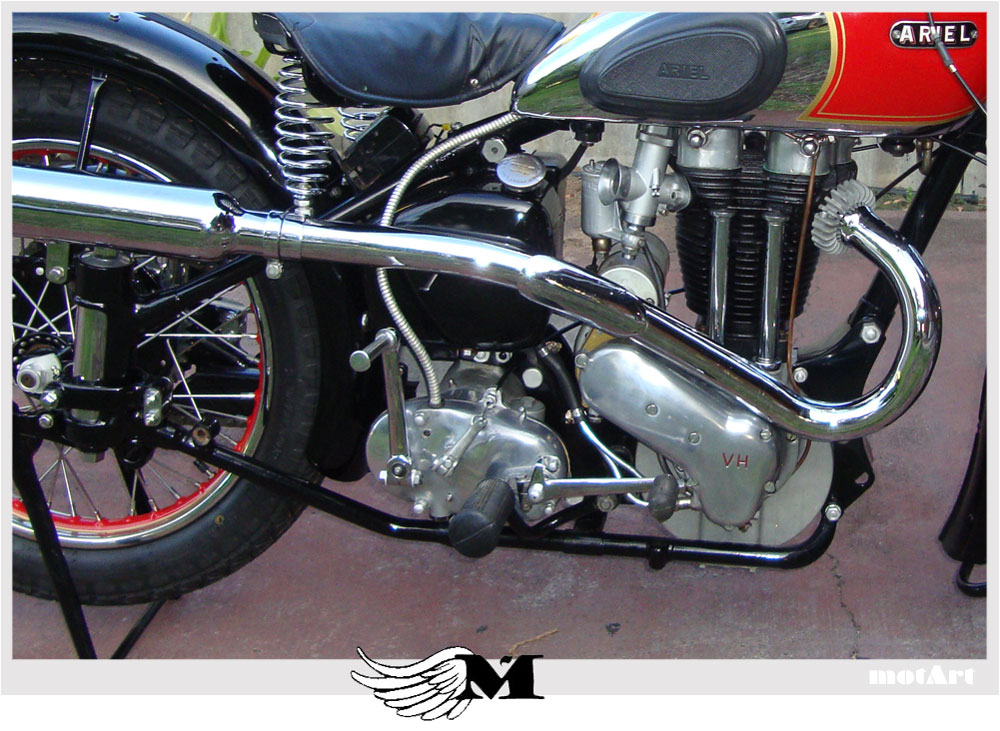

Readers of the Motorshed Cafe will know of our attraction to Ariel motorcycles.

Michael Busby sits astride his late father’s 1956 M50 Norton 350 restored by us here at the Motorshed (see the story elsewhere on this site). It was Chris’ dream to take the Norton to Albany but sadly he did not get the opportunity. His family honoured that dream.

by Dan Talbot | Apr 5, 2020 | Events

This week I was lucky enough to experience my first ride on an Ariel Square 4. These unique machines are quirky, relatively powerful and highly collectable. It was a joy to ride. The motorcycle that I rode was part of a deceased estate which consisted of some 12 operational motorcycles and tonnes of parts, certainly enough to build another 12 machines. As soon as I walked into the shed and saw the bikes and spares laid out, I said, “this must be Ernie Serles’ collection.” As I said those words, it stuck me, with this being a deceased estate, Ernie had passed away. Until that moment I was unaware of Ernie’s passing.

Ernie had been a great help to me when I first built my Ariel and sidecar, most notably when I had major gearbox failure. The following excerpt from Rebuilding the Ariel describes the ecstasy and agony of vintage motorcycle ownership. The excerpt takes up soon after my 1951 Ariel Red Hunter and Dusting sidecar hit the roads for the first time.

This is how we rolled in the mid to late nineties. Evidently, by the time this picture was taken, Emily had graduated to a proper helmet, whereas Molly was still young enough to get away with her bicycle stack hat.

The outfit was finished off and licensed just in time for the annual Biker’s Limited, Perth Toy Run. This would be our maiden voyage. The toy run consisted of a ride of about 20 kilometres from the Southern Perth suburb of Applecross down the Kwinana Freeway into the city. Back then the toy run attracted upwards of 10,000 people.

I had often participated in the Toy Run on my road bikes, way back to the early days of the toy run, when I had my first Harley. On this day I put the kids in the sidecar and off we went. They looked so cute rocking around in the aptly named ‘boat.’ Emily and Molly were both under six years of age and therefore were excluded from wearing full crash helmets. They were allowed to get by with their lightweight bicycle stack hats.

As expected, thousands of bikes turned out for the Toy Run however, many more thousands of spectators lined the route to watch the procession. Sidecars were few, add the two kids in a vintage machine and all of a sudden the whole world seemed to be hooting, waving and hollering at my kids. The ride to the start of the Toy Run was mechanically uneventful, which was a relief as this predated mobile telephones and if, for some reason, the bike stopped, contingencies were few.

M is for Motart. Soon after my Ariel Red Hunter restoration was finished it was featured in the highly exclusive Motart Journal operated by Mr Frank Charriaut. https://themotart.blogspot.com/

Soon after the start of the ride, we had not travelled too far before a police car hailed us to a stop. I was both curious and apprehensive, what did these guys want? Even though I was a detective I still had a fair knowledge of the Road Traffic Code and I felt sure my kids did not need full crash helmets as the heavy appendage could do more harm than good on frail young necks? Aside from that slightly grey area, I didn’t believe I was transgressing any laws.

The Traffic Cop came running up to me clutching a piece of my bike, ‘she’s falling apart on you mate,’ he said as he handed back goodness knows what. I took the wayward piece of hardware with relief. I probably out-ranked the traffic cop but a brush with the law is still a brush with the law! That sounds a little odd but, back in those days, detectives and traffic cops had quite a begrudging respect for each other’s role. Anyway, the piece of motorcycle was dumped into the boat with the kids and we went on with the business of delivering toys to the needy.

We continued on into the city and slowed to the inevitable crawl for the last couple of kilometres. By now, the oil in my engine had thinned to the consistency of water and was seeping through every gasket in the engine. The hot oil running over the barrel gave the impression to anyone nearby that the bike was on fire as smoke rose all about me. Sure there were oil leaks but what couldn’t be fixed or plugged could be passed off as another British motorcycle idiosyncrasy. I wasn’t too concerned, or at least I attempted to portray a nonchalance that made it appear I wasn’t concerned. We rumbled into the city and my children deposited their toys for the kids who were too poor to be visited by Santa – a tough subject that one.

After the Toy Run I dropped the little ones at my mother’s house in nearby Victoria Park and continued on home with an empty chair. All in all, I felt pretty chuffed with myself. It had been a good run and the bike performed well but, most of all, my plan to share the joys of motorcycling with my children had come to fruition. The kids had a ball and I was pleased everything went so well. Now that my girls have grown up, it is times like these that one reflects upon as highlights along the road to raising children. Simple pleasures.

Well, maybe not so simple. It had taken lots of time and money, commodities that were both in short supply around the Talbot household back then, to get to this stage. Lots of trial and error, lots of skinned knuckles, lost temper and cursing as I bumbled my way through tasks hitherto unknown to me. But, in the end, I had turned out a quite remarkable piece of motoring history, I was very pleased with myself. Then, all of a sudden, the bike ground to a stop and the big cheesy grin fell from my face. I was only two kilometres from home, a situation for which I should have been extremely grateful because, as it turned out, I would be walking the rest of the way.

I couldn’t tell what was wrong with the bike but knew for sure it wasn’t good. I couldn’t move the gear lever and the only way I could get the bike to move was with the clutch drawn in. What followed was a two-kilometre push home. It was hard work and, as I was trying to avoid using the road, I stumbled forward keeping as far left as I could. This led to disaster number two.

About halfway home I banged the sidecar mudguard fair into a lamp-post, kinking the metalwork that had been lovingly hand-painted by me using lots of rubbing back and building up with several layers of spray-pack paint. It sounds odd, but with lots of work I actually turned the guard into a splendid addition to the outfit. Now it was scratched, bent and buckled and I was cranky. I was really starting to think ‘are vintage bikes really worth the trouble?’

Despite arriving home mid-afternoon, dehydrated, sunburnt and exhausted, I immediately set about removing the seized gearbox. As tired as I was, ripping the gearbox out sitting on the garage floor, from memory, went quite well. It was the first time I had done such a thing so I was kind of pleased to finally lift the gearbox out of the frame just as it was getting dark. What a day it had been.

The Ariel gearbox is ordinarily a sturdy piece of equipment but I managed to seize it.

Following the seizure, with the gearbox out, I took it off to a fellow from the Vintage Motorcycle Club who lives and breathes Ariels. At that time, Earn had a large shed at the back of his Bentley house. It was chock full of Ariels and Ariel parts. Being December, it was also unbelievably hot inside Ernie’s shed. As soon as I handed the gearbox over he was off down to the workbench, whereupon he secured it in the vice and got to work. I stood silently alongside Ernie as he beavered away on my gearbox, for as long as I could bear the heat, then blurted out, ‘umm, Ern, I’m actually on my lunch break and really need to get back off to the office.’

Ernie waved me off without lifting his head, I made my way back outside and found it was almost a relief to be outside in the hot December sun. Ernie rang me a few hours later to advise he had located the problem. It was an offending brass bush that had a distinctive home-made quality about it (in fact, as it turned out, a lot of things on the Ariel had a shoddy, home-made quality). Evidently, the bush did not have sufficient journal for oil to flow and, with the added load of a sidecar, the bush got hot, expanded and locked the shaft. A $5.00 replacement was all that was needed.

When I went to pick the gearbox up, Ernie had left instruction with his wife that he wanted $5.00 for his work, and $5.00 for the bush. Naturally I left much more than that, amidst protestations that is was far too much. 25 years later and the gearbox still works as good as new.

Ernie’s ’54 Ariel Red Hunter sits alongside his ’56 Square 4. Two highly desirable and collectible motorcycles.

The late Ernie Serle’s 1956 Ariel Square 4. The old bike is in tip-top condition, starts first or second kick and runs like a swiss watch. A truly remarkable machine.

I took this photograph of a Square 4 outfit at the annual Indian Harley Club 2 Day Rally in 2018. Note this is the earlier, Mk 1, machine. The exhaust exits the front of the head, unlike the Mk 2 (above) which has four pipes (two each side) which was said to aid cooling.

by Dan Talbot | Dec 7, 2019 | Collection, Projects

When we left off with the last instalment, the little Norton was parted out here, there and everywhere. Readers and interested parties will be happy to know most of those parts have been renewed and, if not back together, they’re at least back in the shed. One such ‘part’ is the engine.

For a 350 cc machine, the engine in the little Norton is a substantial lump of iron and alloy. This is understandable as essentially the engine started out as a 500, only the internals are different. In fact, the whole bike is basically a 500 ES2, albeit with 350cc. This actually makes it quite rare. By the mid nineteen-fifties young men in the UK were craving larger capacity machines and would overlook the M50 in favour of its big brother. Many of the 350 cc bikes that were purchased had the single cylinder engine taken out in favour of a larger twin, such as that found in the Motor Shed Triton.

The 350 cc Norton single.

You’ll recall the story of the Triton, a parts bin special created by throwing a Triumph twin engine in a Norton frame? The featherbed frame, which is discussed at length in the Triton story, was a huge success for Norton. The twin down-tube, cradle style frame was to become the signature to the Norton motorcycle racing effort. They had long proven they had the best engines, the featherbed frames simply helped the company assert their racing credibilities and maintain their dominance in the two-wheeled, racing world (I’m sure that’s poke a hornet’s nest so hit me with your best shot :).

Elsewhere in the range, the single down-tube frames were left for commuters, tourers and those wishing to fit sidecars – which were a big thing in Britain as the country recovered post-war. The Buz Norton is of the second group, not a risk of losing it’s engine older, single down-tube, ‘pre-featherbed’ frame. I say this in parenthesis because they were never actually referred to as pre-featherbed,’ this is a retonym used by various people and groups, such as parts suppliers – some of whom I’ve become intimately acquainted with.

The fuel tank, single down-tube frame and engine before restoration. Note the sidecar lugs on the frame (visible near each end of the fuel tank).

Andover Norton has been the preferred parts supplier. They are very fast in getting gear out to Australia but as far as the singles go, parts are limited. I’ve also found the catalogue is not too accurate, which has resulted in me receiving an axle that doesn’t fit. “And where’s the original axle?” I hear out there on the ether. Being a basket case, which by definition is a jumble of bits and pieces, some things have inevitable gone missing. The rear axle being one such item.

One of the hazards of international purchases, they don’t always fit.

Speaking of axles, we have two freshly build wheels waiting to be fixed to the machine. They are brand-new, stainless rims and spokes laced to freshly vapour-blasted hubs. They look fabulous. Shiny, but not too so. The modern rims and spokes, together with the original, sturdy hubs have resulted in some tidy rolling stock. It will be a long time before these wheels wear out.

The new front wheel. It will be a long time before this one ever wears out.

Elsewhere on the bike, having done the math, it was economically and mechanically sound to dispense with all the broken and rusty clutch parts in favour of the beautifully crafted Bob Newby belt drive. These things are a work of art that would ordinarily over-capitalise such a machine as the M50 but there was simple nothing that could be salvaged from the original clutch so picking up a Newby belt drive and clutch set up has saved money, added reliability to the bike and lessens the likelihood of oil escaping the primary, because there’s simply none in there.

The Newby belt drive. A work of art that, sadly, won’t be seen.

The engine is snugged up, back in its rightful place. With vapour blasting shining all the alloy pieces and a lick of pain or plating on the metal components, the engine is looking as good, if not better than new. Plating consist of chrome or cadmium, the former costs a king’s ransom, the latter is not so bad. Like other forms of metallurgy, chrome plating, when done right, is of much higher quality than in the days when the Norton first travelled along the production line, which is what we’re aiming for with the whole bike.

Metalwork prior to cadmium plating.

Metalwork after cad plating.

Engine top end – before.

Engine top end – after.

Chrome-plated items.

The rear guard is back from the painters and is so shiny you could do your hair in the reflection.

by Dan Talbot | Oct 2, 2019 | Collection, Projects

I was recently having a chat on messenger with Mr Fritz Egli himself about Nortons, specifically the modern incarnation of the 961 Commando, such as that which lives in my shed. Suffice to say Fritz is not a fan of the new Norton however I enjoyed tapping into his knowledge base, even if he did insist on telling me how bad he thought the Norton was. Anyway, after I figured we had developed a comfortable rapport, I clumsily steered the conversation towards my “Egli” build. Without another word Fritz left the conversation.

Mr Egli is quoted in Philippe Guyony’s 2016 publication Vincent Motorcycles, The Untold Story since 1946, on the popularity of unauthorized copies of his famous motorcycle frame design, “The were more than six workshops manufacturing and selling unauthorized copies of my frames all over Europe as the genuine ‘Egli-Vincent.’ of course, at first I was upset, but soon I regarded it as a compliment to my design and then I moved on (2016, p.6).”

I’m prompted to rename my project, I’ve been thinking of the Triple T (Taylor, Talbot, Triumph). Comments and suggestions for a name are welcome at the bottom of the page.

In the interests of revision, and for those that are new to this project, Colin Taylor, who has built over 90 Egli-style frames, was tasked with building a frame for me to plonk a T150 Triumph 750 triple engine into. It is my intention to build a mid-seventies, part hot-rod, part superbike, special. An almost unique machine that will go as good as it looks. I say ‘almost unique’ because, as best as I can tell, there is only a handful other Triumph triples living in Egli-style frames that I know of. Indeed, Egli himself is rumoured to have built two frames for Slater Brothers in England to fit triple engines to and authorized the construction of another 12 by specialist frame builders in the UK at Slater’s direction. This was something I was about to discuss with Fritz when he terminated our conversation.

Tapping into online resources I’ve identified at least three Egli-style T150 motorcycles in France, one in Norway and the below pictured machine owned, crashed and burned by Marc Maslin in the UK. Marc’s motorcycle was one of the original Egli authorized copies and therefore comes with the blessing of Fritz himself. Sadly Marc’s bike underwent a Viking funeral (as Marc puts it) and is now resting peacefully in Valhalla.

Marc Maslin’s original Egli Trident T150v. The 850cc Triumph engine was fitted with a lightened and balanced crank, breathed through 30 mm carbs, had a gas-flowed and ported head, lightened and balanced pistons. Upgraded oil pump and enlarged oilways.

At the time of contracting Colin for the build I didn’t actually have a T150 engine but they are certainly easier to come across than the Vincent engine synonymous with the original design. I expected it would be a short time before I located a suitable engine, but, instead, I’ve been locating whole bikes, albeit barn-finds and basket cases. I now have a ‘71 BSA Rocket 3 and a ’74 Triumph T150, neither of which I’m willing to sacrifice to the build we are discussing here. Incidently, the causal relationship between the BSA and Triumph triple engine is a fascinating topic that can be read here.

I also have an assortment of T150 engine cases, crankshafts, heads and other engine parts that I have brokered and bartered for over the past couple of years. To the casual observer it might look like I have enough bits to build three engines but most of it is quite poor quality and certainly won’t withstand the rigors of what I’m intending on building, however it does serve a purpose which will become apparent below.

Over the past few months I’ve been able to amass a few Triumph T150 engine cases and parts.

In August this year my wife and I returned to the UK and our favourite place in the world – the Isle of Man. In travelling to the Isle, we flew into Manchester and boarded a train for the one-hour ride to Liverpool. Sitting at the top of platform 5 in Liverpool, Lime Street Station, was Colin Taylor with my brand-new, nickel-plated, motorcycle frame. After many emails and me sending a not inconsiderable sum of money to Colin in the preceding months, we finally met face to face. I’ve read a lot about Colin and his creations and have seen his photograph numerous times in the motorcycle press so it was quite special meeting the man and being regaled by his jokes and general banter.

The author finally meets the specialist frame builder Colin Taylor – and takes delivery of the newly finished frame for our Triple T special.

I would love to say I was giving Colin my undivided attention but, in truth, I had one eye fixed upon my frame sitting on the floor of a very busy English Liverpool pub, dividing my time between that and chatting to Colin about all things motorcycling. We broke bread and drank Guinness and had a pretty good afternoon before Catherine and I made our way down to the ferry terminal and Colin headed off back to Nottingham (although he is an Englishman, Colin lives and builds his famous frames in Italy. I’ll leave Colin to add his contact details to the bottom of the page for anyone wanting to build a special).

I slung the frame over my shoulder and we set off on foot for the two-kilometre walk to the docks to board our ferry to the Isle. Along the way, a few curious onlookers, recognising a motorcycle frame, asked what machine it was intended for. If the frame sparks this much interest, imagine what the finished bike is going to do.

The frame is packed and ready for the long journey to Australia.

A week later, after an exhausting, 24 hour, non-stop journey from the Isle of Man to Busselton, Western Australia, we finally arrived home. I went straight out into the shed and tried my frame against one of the T150 bottom ends I have stashed there and, guess what, she fits.

So now I have my frame and my T150 donor bike, there’s one small problem. I can’t possibly separate the engine from this bike. This is a matching number, time-capsule from 1974, parting it out is not an option. Phil Irving, the Australian engineer responsible for designing the Vincent V-twin engine, in his 1992 Autobiography wrote, “there were those (including myself) who considered that every new Egli meant one less Vincent (1992, p.514).” I have no doubt many fans of the Triumph T150 would feel the same way. Sure I’ll take the odd part from the T150 but, when this project is done and dusted, that T150 will be the next machine to undergo a full restoration, to be brought back to its former glory. In the meantime: does anyone have a spare T150 engine they don’t need?

Up until now, this bike has been referred to as a ‘donor,’ insofar as the engine was intended as a base for the project. Having now secured the bike and moved it to our shed, this matching number survivor machine is too good to part out for a special and will eventually be returned to the road in original trim.

Despite the rust and dust, this motorcycle has had very little use. It was last registered in Ohio in 1981 and represents a true ‘barn-find.’