by Dan Talbot | Nov 1, 2021 | Events

What’s not to love? A week off, 60 veteran and classic motorcycles and some of the best scenery WA has on offer. The WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally was a victory snatched from the jaws of the defeat that arrived in the form of the pandemic-generated travel restrictions. I was lucky enough to accompany the rally as an official on a relatively modern machine from 1948, these are some of my observations.

A remarkable thing one notices when casting an eye over a field of veteran motorcycle riders is they are mostly quite fit. We’ll get to the reason for that in a moment. If you’re reading this, chances are you’re a motorcycle enthusiast and you have an actual motorcycle parked out in the garage. Now, let me guess, that motorcycle has brakes? Brakes that will bring your machine to a stop? I’m also guessing it has a clutch, perhaps a kick starter, or, luxury of all luxuries, an electric start? And don’t get me started on gears!

Geoff Birkin’s Abingdon King Dick wins the award for best name.

The Indian Harley Club of Bunbury recently hosted the WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally in Manjimup, 300 kilometres South of Perth, Western Australia. Originally slated as a national rally with in excess of 100 entrants signed up, the event had to be scaled back to a state-based one due to travel restrictions placed upon some 60% of participants. Nevertheless, the event was a huge success with almost 40 entrants, many of whom brought more than one machine.

In the hierarchy of old, veteran is the oldest. To participate in the WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally, machines had to be manufactured prior to 1919. Added to the mix was another 20 marshals riding classic and modern machines, including your correspondent who wore the Clerk of Course tabard. Which was quite an honour for me.

In general terms, veteran motorcycles start at about 500 cc and go up to 1000, or, in one case, 1240 cc. Bob Wittingstall’s 1150 Sears Dreadnought is a single speed, V-twin, behemoth that could be ordered from the 1913 North American Sears and Roebuck catalogue. The Sears is pedal-started in gear with the rear wheel off the ground. With the engine running, the rider moves the gear lever to neutral and pushes the machine off the rear stand. The gear lever is pulled back and off you go. Braking is taken care of by the back pedal method: just like mid-twentieth century bicycles. In fact, many of the veteran machines at the rally bore a striking resemblance to bicycles or the era, from which they were created.

Bob Whittingstall entrusted his 1913 Sears to his friend Tim to ride during the 2021 Veteran Motorcycle Rally.

I must say, at the beginning of the twentieth century the Americans may have possibly had the edge over the Brits in terms of motorcycle refinements. Harley Davidson, Indian, Thor, Yale, Excelsior and the afore-mentioned Sears had clutches, gears, kickstarts and massive V-twin engines. What they all had in common was rudimentary suspension and next to no brakes but, to this intrepid band of motorcyclists, that kind of adds to the attraction. Even grinding to a stop seems to fill them with glee and riders and support persons beaver over stationary machines in a frantic endeavour to avoid being trailered back to camp. Most often they got them running again, including an impressive top end rebuild by Michael Rock on his 1915 Triumph outside the Pemberton Hotel during the lunch break.

Repairs on the run were very much the order of the day. Here Steve Merralls works on his 1913 Triumph at the Northcliffe lunch break.

With the exception of the American twins and perhaps half a dozen other machines, most of the veteran motorcycles at the rally were started by peddling or pushing, requiring a fair degree of physical rigor in either case. An energetic rider must get up to a decent pace, running alongside his machine (there were no female entrants this year, but they are out there!) then launch himself onto the saddle as the bike fires once, twice maybe three times. Stop signs, traffic and other inconveniences are negotiated with care, lest the rider must dismount and do it all over again, which was frequently the case.

The rally went from Sunday to Friday through some of the most picturesque countryside regional WA can offer. Manjimup people, shire and shopkeepers can take a bow. They were the perfect hosts for a quirky bunch of folks riding an even quirkier bunch of motorcycles. Patience was quite often called for as motorcycles and side-cars chugged along at 30 or 40 kilometres an hour, so a tolerant community was very much appreciated by the dare-devils piloting the ancient machines.

Main Street Maniimup.

We travelled as far afield as Northcliffe, Pemberton and Nannup. Technically, Nannup was cancelled due to foul weather however a few hearty souls, including your correspondent made the trek to Nannup via Donnelly River. It bucketed down on us and the water found its way into a few of the vintage magnetos but, aside from that it was a wonderful day, typical of the entire week. The Indian Harley Club, Manjimup Tigers Football Club (who catered for the event) and people of Manjimup are to be congratulated.

Kelvin’s 1914, 1240cc Thor, another American V-twin of extraordinary beauty.

Dave Anderson prepares his 1913 Triumph for the day with a new leather belt to help cope with the expected bad weather – which causes the belt to slip and forces the riders to push their machines up some of the more challenging hills (which, it must be said, also happens on sunny days with dry belts).

Steve Turner basks in the knowledge his Australian made Corah was the loudest, and some would say, sweetest sounding single in the event.

The Tuesday ride was cancelled due to inclement weather however the more stoic riders still ventured out. Here one of the locals creeps up on some of the participants at Donnelly River.

Marshall’s bikes were usually parked up away from the main veteran group.

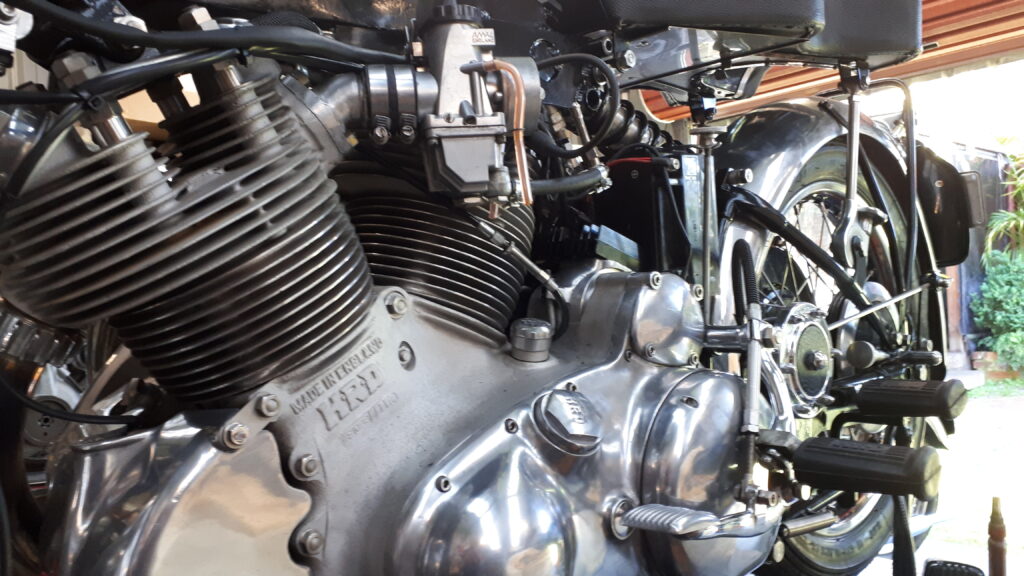

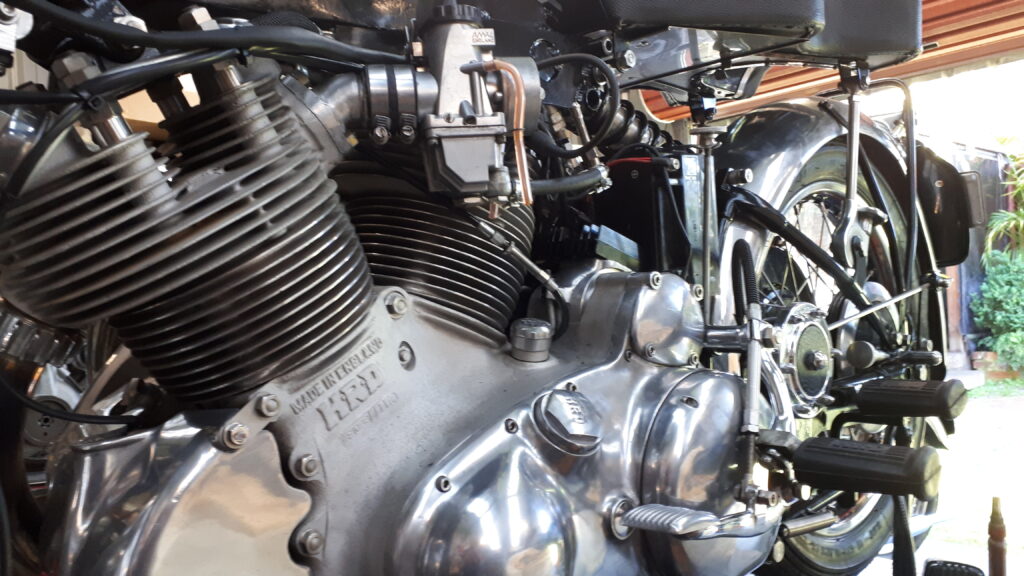

The Clerk of Course, and your humble narrator, enjoyed a week of classic touring on my 1948 Vincent HRD, a relative youngster by the standards of the event.

Read more about the Vincent here and here.

Regular readers will understand why I posted this very tasty 66 Mustang Fastback.

You can read more about Mustangs, one in particular, here, here, and elsewhere on the Motorshed Cafe site.

Another Classic Ford, this one was Chris Merrall’s support vehicle, with Dad Steve at the wheel.

Another Australian made motorcycle, Rob Giles’ 1914 motorcycle named The Lewis sounded as good as it looks.

Another Marshall’s machine.

John Keenan is about to lose what’s left of his icecream – ironically a drumstick.

At the end of the week it was time to pack up and go home.

If that Penny Farthing has piqued your interest, read more about it here.

by Dan Talbot | Oct 7, 2021 | Uncategorized

Vincent HRD owner’s review

10,000 kilometres

By Dan Talbot

Mercury is the God of eloquence, merchants, travelers, thieves and wisdom. I’m not sure why the Romans threw thievery in there but, in his defence, Mercury was the father of Cupid and one of the Olympians so that must give him some kudos and may help explain why I am so taken by Vincent motorcycles. It is little wonder Vincent emulated the Isle of Man TT trophy of Mercury rising upon a motorcycle wheel as their tank motif. Mercury takes front and centre when I’m sitting on my Vincent gazing upon the beautiful work of master engineers from the middle of last century. He reminds me of how lucky I have been.

Over two years and some 6,000 miles (10,000 km) down the track of Vincent ownership, I figured it was about time to write an update on where I am at with my 1948 Vincent HRD Rapide. There has been a few trials and tribulations associated with my machine but this was perhaps to be expected due in a large part to me purchasing a motorcycle that had covered only a few miles since it was restored. At this point it would be useful to read my earlier piece introducing the Rapide back in 2019.

Fresh of the docks in Melbourne (the bike, not me). As soon as I was able, I flew to Melbourne to check out my Vincent, the realisation of a 40-year dream.

When I took delivery of my Vincent I (foolishly) expected I would be able to get it registered and ride off into the sunset. Naturally this never happens with a new restoration and it has taken quite a lot of fettling to get things right. Aside from the obvious frustrations that will unfold below, bringing my motorcycle into a ridable state has been a tremendous learning curve, that I am only beginning to climb. There’s an adage out there that says “Norton, making mechanics out of motorcyclists.” I won’t argue with that, my Norton problems are well and truly documented but one could easily transpose ‘Norton’ with ‘Vincent.’

My Rapide arrived with Mikuni carburettors. Mikunis are a very good hardware and I’ve used them to great effect on other British motorcycles I’ve owned, including my Triton. The Triton has a massive, Mikuni pumper carb and she flies. Again, there was lots of trial and error in getting that machine running correctly and some of the lessons I learned in tuning the Triton’s old pre-unit Triumph engine would later be applied to the Vincent. I had dreamed of owning a Vincent for over 40 years and during that time had devoured countless books, magazines and, more recently, online resources. I could close my eyes and vision the machine I would one day own and never once did it have Mikuni carbs. On my Rapide they hung there like transplanted dog’s bollocks and I just couldn’t get my head around them. I needn’t have worried too much, the Mikuni’s had a built in obsolesce in that the bike was not running very well under their stewardship. It was an easy decision to dispense with them.

Not for aircraft nor Vincent.

A friend sent me a pair of Amal Mk2 carbs he had removed from his Vincent when he bombed it out to 1200cc. At one litre, Holger’s Vincent ran well with the Amals but when he went for the big-bore kit he opted for a pair of larger, pumper carbs which left the Amals looking for a new gig, enter the awakening. The rub here is that Amal Mk2 carbs were made under licence to Mikuni. So here I was, removing perhaps the world’s most reliable carburettors from my motorcycle to replace them with a dodgy British imitation. Mad, I know. It didn’t work either. I persevered with the Mk2’s for far too long but could not get the machine running right (nor could some experts well versed in the art of motorcycle tuning). I even changed the ignition from Pazon to Trispark, but that didn’t help either. Eventually, a friend offered me a pair of brand-new, unused Amal Premier carbs apparently jetted for a Vincent twin. They worked a treat but not without some radical changes to the manifolds.

For a time, I hoped Amal Mk2 carbs were the answer. Sadly after a great deal of time and money neither myself nor people ‘in the know’ could get these carbs working. They were subsequently set aside.

The solution came in the form of two brand new Amal Premier carbs.

The Mikunis and Amal Mk2 use rubber sleeves to hold the carbies to the manifold stub. The carbs held in place by worm drive clamps. The Amal Premiers, on the other hand bolt up to manifolds, which in turn bolt to the heads. Such is the design of the Vincent engine, the two manifolds have subtle differences to accommodate the correct angle for the carb to sit at. That is, each manifold has a different angle. In fact, the manifolds had enough angles to confuse Pythagoras. Now, I am no mathematician, but two manifolds, each with two surfaces, equals eight possible combinations, there may as well have been 800, there was no way I could get the rear carb to sit correctly. Eventually, I went off on a ride, a long ride, with my wonky carb. Sitting at a pub having a lunchtime beer, a fellow enthusiast voiced what I knew to be true, “that doesn’t look right.” “No, it doesn’t. Hold my beer.”

Amal carb listing.

Off came the carbs again and more moving and swapping of the manifolds took place, this time with about six very experienced classic motorcycle enthusiasts present, two of whom owned Vincents and they too were stumped. I made it home but, in the end, out of shear frustration, I cut the manifold in half, reset and marked where I wanted the flange to sit and trotted off to a welder. The result was infinitely better, but still not quite right. I needed balance.

Aside from Zen, what I needed was for the carbs to open and close at the same time. I decided I needed a pair of mercury gauges. Seems reasonable, a factory decal of Mercury riding upon a wheel sits in the middle of every Vincent fuel tank. Whilst waiting for the delivery of my mercury gauges, in a nod to Heath Robinson, I used a makeshift setup that involved placing a long meat skewer under the slide of each carb (I can hear the moans, but stay with me). I set the Amals to raise and lower the skewers in unison. Then I had it – a perfectly running 1000cc V-twin engine! Off I went.

I can hear the groans from here. That said, my rudimentary carburetor synchronising tools worked. Eventually I had a perfectly running V-twin engine.

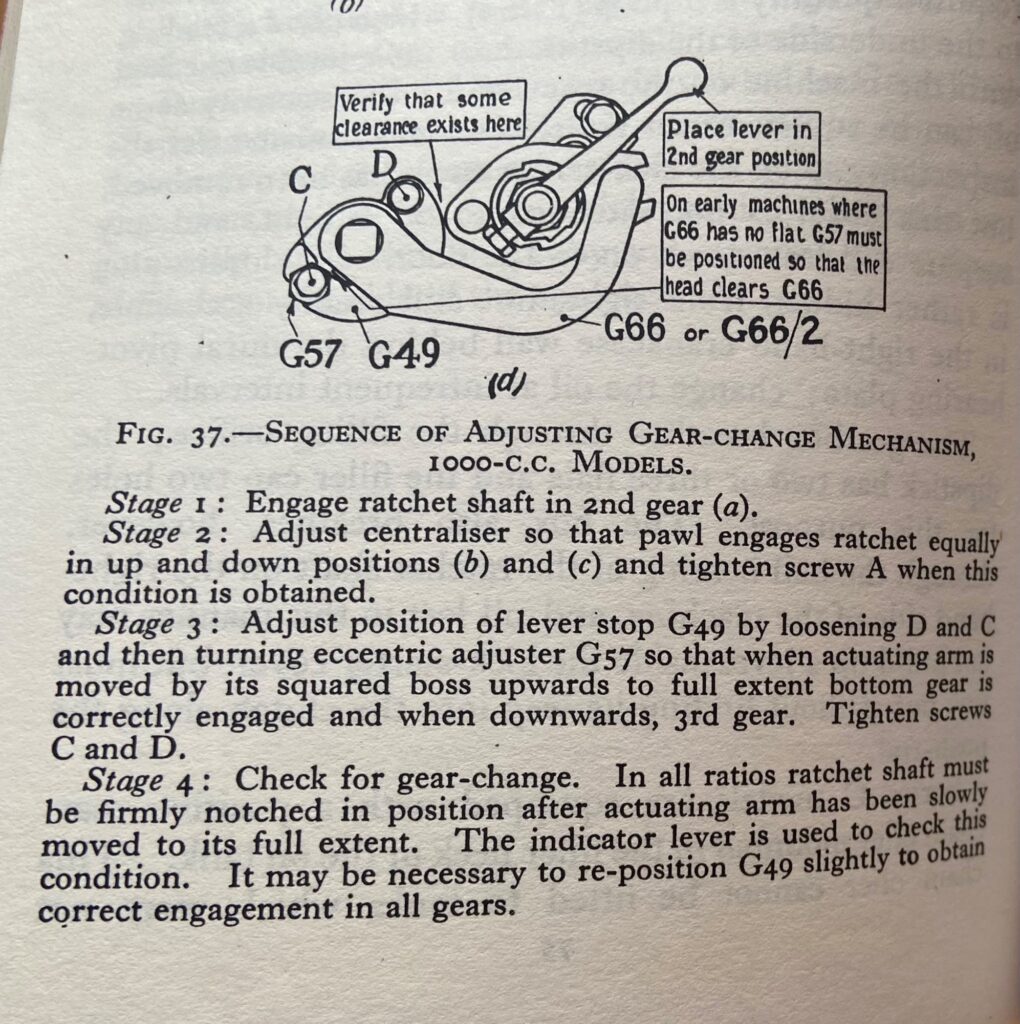

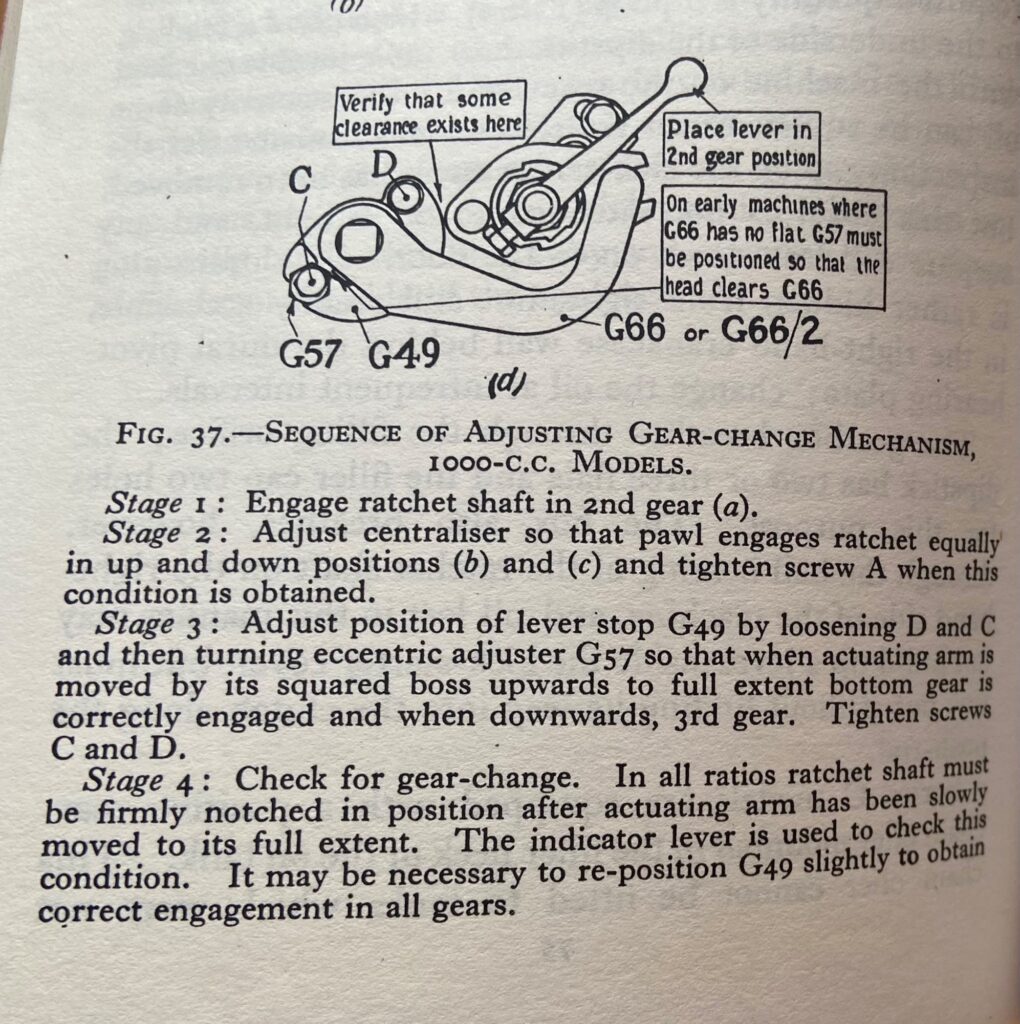

About 20 kilometres from home I lost second gear. There was no grinding or crashing coming from the gearbox so I headed off home. Gear selection was hit and miss but I made it. Having arrived home, I hit the computer and found out what the problem was. I set about rectifying the wayward gear selector according to the brightest and best mechanics google turned up and promptly lost all my gears. Long story short – I turned to the Paul Richardson’s 1955 book Vincent Motor Cycle Maintenance. There is a four-stage process that takes one through the correct setup that, on this occasion, was lost because of a loose bolt on an internal adjustment device called a ‘pawl,’ but mostly referred to by the Vincent Illuminati simply as ‘G59.’ I was beginning to understand everything in Vincent nomenclature was defined by part numbers. To this new owner, it’s equal parts civilised and alien.

And that’s how it’s done.

With my gears sorted, I ventured out again, but not before having a crack on a forum about Vincent letting the work-experience kid engineer the gear selection mechanism. I was rigorously chastised by the Illuminati putting me firmly back in my newby box. The mere act of turning up on a forum signals one’s vintage along the road of Vincent ownership and I was called out as inexperienced (true), incompetent (in my defence, I was mobile) and inorganic. I’m not sure where that last one came from, maybe someone thought I was a cyborg, or, maybe spell checker jumped from ‘ignorant’ under the furiously tapping, albeit arthritic, thumbs of a Vincent enthusiast. In any event, 6,000 miles later and there’s been no more troubles from the gear selection, save the occasional jumping out of third gear, so my crack at the work-experience kid was probably not warranted.

The next big thing was the clutch. My Vincent was fitted with a late-model, replacement clutch manufactured under the banner of V3. The V3 clutch is a gem. It simplifies what was a complicate servo unit that the faithful will defend to their last breath but those of us who actually want to put miles on their Vincents invariably turn to an after-market clutch. Soon after I got out and about on my Vincent the V3 began slipping. The problem was eventually found to be the lockring, hang-on, the G45, that holds the gearbox main-shaft bearing in place. This allowed the main-shaft to gradually drift to the left against continual adjustments by me to the clutch in a futile attempt to lessen the slipping. When the lockring finally came all the way out I lost any semblance of a clutch and the bike had to be trailered home. That the gearbox suffered no lasting damage seems to confirm Richardson’s 1955 assertion they are ‘unusually robust.’

A brilliant piece of Vincent kit manufactured by Paul Alton in France.

I’ve touched on the ignition above. The changeover from Pazon to Trispark was driven by equal parts experimentation and frustration during early ownership of the Vincent. In hindsight, it probably wasn’t needed. Pazon is a perfectly good product, and so too is Trispark, but they rely on a power source. My ignition preference is the magneto. A magneto generates its own spark so the engine does not rely on a battery. Back in 1948, when it was new, my Vincent had a magneto and I would like to revert back to one, albeit a brand-new, modernised unit. However, the bike is running beautifully at the moment and in the back of my mind there’s a voice saying ‘don’t dick around with things that functioning as they should.’ I’ll probably stick with the Trispark and enjoy continued reliable ignition. With the Trispark being dependent a charged battery I ditched the original, dodgy generator in favour of a new Alton unit. If any of the Vincent Illuminati are still with us they’ve just spat their Cognac out – all over their computer screen.

With the Alton in situ only the truly strident rivet-counters would recognise this as a modern generator.

The Alton 12-volt generator uses permanent magnets, like the old dynamo on my pushbike when I was a kid. In an automotive application it works a treat, maybe even too good. After a particularly spirited ride with a couple of chaps on modern sports tourers a few months ago, the battery gave out. It was suggested to me the Podtronics regulator could have been faulty (as they are apparently known to be) and at continued high speed riding, with the generator pumping a full 150 watts into the battery for over an hour, may have cooked the battery. That ride brings me to another topic – speed.

Once the bike was fully sorted, the next problem I found was the speedo to be faulty. As it turns out, the after-market, twin-leading shoe brakes were fowling the speedo drive. Repositioning the drive gear corrected the intermittent nature of the reading but the speed was extraordinarily high and I needed to recalibrate the speedo. To do that, I fitted a small GPS speedo. The GPS revealed: when the speedo was showing 70 mph, the GPS was showing 112 kph. And when the speedo was showing 90 mph, the GPS was showing 145 kph. I won’t go on out of fear of incriminating myself but you get the picture. The speedo was accurate, I was actually traveling at the speeds indicated by the 72 year-old speedo! On the 72 year-old motorcycle.

On a final note, the bike has a great hunger for rear tyres. It may be the modern compounds are too soft, or combine bike and rider is on the heavy side but, on average, I have been getting about 2,000 km per tyre, which is not very good.

So, there we have it, up to today. The major gripe I have now is oil leaks. The Vincent is like a recalcitrant puppy leaving puddles wherever it goes. There is a fix at hand but I won’t go into that just yet in case any of the Vincent Illuminati are still reading.

I’ll have that beer now.

I thought the speedo was reading on the high side. Calibration with a GPS proved not. I was actually going that fast!

The tank decal had to be replaced with a more authentic HRD item. At the same time, the tank was given a new coat of clear. This was the result.

The Vincent HRD explanation.

Phillip Vincent was undoubtedly a very talented individual. Some folk may have noticed the cantilever rear suspension fitted to my motorcycle. Vincent first came up with this design whilst still in school, no doubt sketching his future motorcycle design when he should have been paying attention to his teacher. By the time Vincent was 20 he had convinced his father to buy him a motorcycle company. Howard Raymond Davies was both a motorcycle builder and racer who could boast Isle of Man Senior and Junior TT race wins on his own machines. Vincent Snr purchased HRD in 1928 and, in a nod to the famous origins of the HRD marque, Vincent retained HRD on the motorcycles up until 1949 when they dropped the three-letter moniker for fear of being confused with that other famous V-twin: Harley Davidson aka HD.

Banner picture by Jeremy Hammer.

by Dan Talbot | Aug 30, 2021 | Projects

This piece has been a long time coming. It is 20 months since I wrote the part IV and well over two years since I first introduced the project. I could come up with a host of reasons why it’s taken me so long to write this but I feel it’s because I don’t want the story to end. The restoration of the little Norton has evoked emotions in me of both pleasure and pain. The pleasurable moments were shared as the motorcycle took form and came back together. The painful was the hideous disease that had robbed Chris of the ability to carry out the restoration himself and would ultimately rob him of his life.

Chris was already quite ill before I was tasked with managing the restoration, I say ‘manage’ because my job was to bring together, coordinate and work with the various experts who contributed to the restoration. During my brief times with Chris, I occasionally had a glimpse of the man that was so popular and loved by so many. As one who dabbles in mechanics and holds a strong interest in modern and classical engineering, I am impressed when I meet people who excel in these fields. Chris was one of these people, his field was electrical engineering. Unlike mechanical engineering, electrical engineering holds an esoteric, almost intangible commodity in the invisible force it possesses. Let me have a clumsy go at describing the nexus between nature, physics and engineering, with a touch of the metaphysical thrown in.

Greek mythology asserts before creation there was chaos. Without electromagnetism chaos would continue to reign. Our very presence on this earth if only possible because of electromagnetism, it holds us together and our planet together. Think of the Taoist Yin Yang symbol which illustrates perfectly the positive and negative forces that are responsible for our collective being. More than just electricity, we can use ancient Taoist principles to demonstrate engineering of strong/weak, hard/soft, heavy/light. Engineers of today still grapple with these principles when designing the machines that we live with each day, motorcycles being a perfect example. The Buz Norton is strong, hard and heavy yet it comes with an inherent fragility of fatigue over time. This is what makes riding restoring and riding classic motorcycles so appealing. Every ride is an adventure, arriving home at the end of the day with the motorcycle still running is a triumph of man over machine.

What we have attempted to do with the restoration of the little Norton is preserve the engineering of the fifties. We rely upon the skills of the original designers and trust in their choices when meeting the challenges of functionality, economy and technology. We have taken the motorcycle to irreducible pieces and examined each piece, deciding whether it stays or goes. Experience tells us what can stay and what can go. Luck tells us that we occasionally make mistakes in these choices and the machine will occasionally fail. Without constant attention failure is inevitable. And that’s where your humble narrator comes in.

I have made some tremendous friendships since embarking on the restoration of Buz Norton and, if that little motorcycle is to remain fresh and mobile, it will take regular maintenance and fettle. I look forward to maintaining the friendships with equal joy that I do in maintaining the motorcycle. For now, the bike runs quite well and will head down the road in fine style, however, the inherent fragility is up around the bend. We just don’t know which bend.

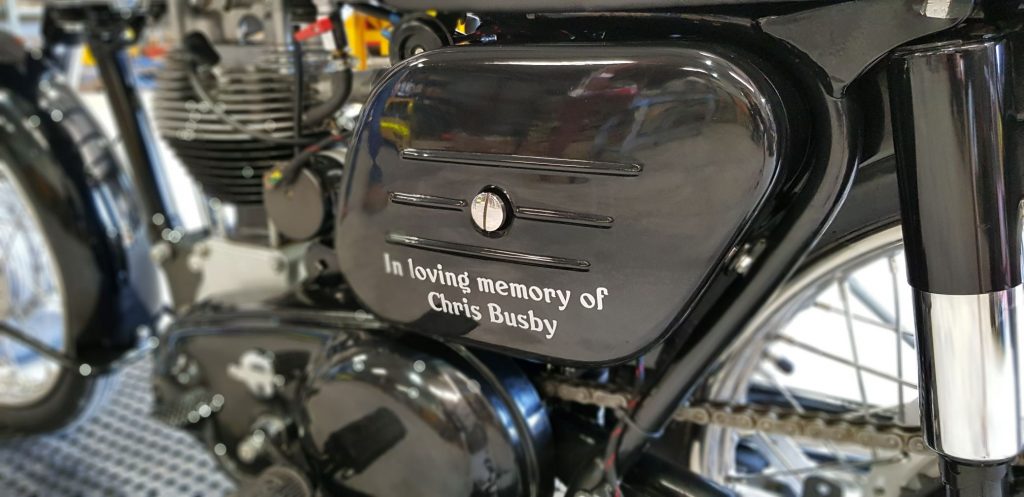

Sadly, Chris passed away soon after restoration of his motorcycle was commenced by us.

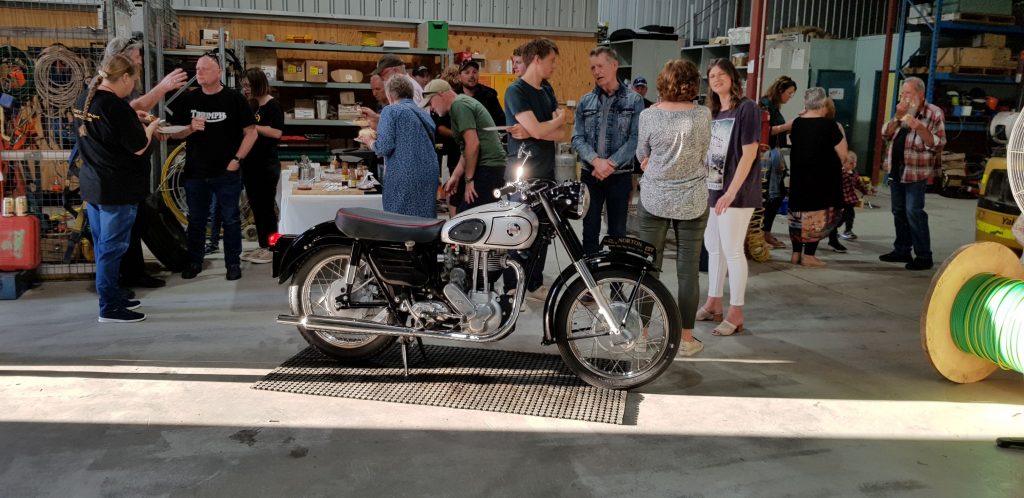

Some of the experts involved in the restoration of Buz Norton.

Three generations of the Busby family stand with their motorcycle.

Something old, something new. A modern Newby belt drive saved the Busby family a few dollars and will last for many miles. Best of all, there’s no oil to leak out of the tin primary chain case cover.

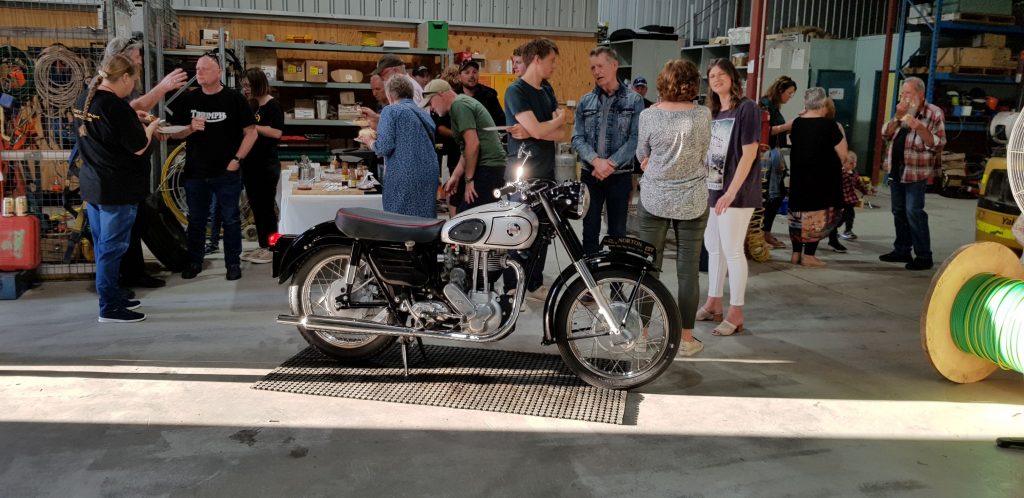

Restorers Dan Talbot, Ray Buck and Bernie McCormack and other members of the Indian Harley Club of Bunbury, Western Australia.

Family and friends of Chris Busby celebrate the completion of the Norton restoration in October 2020.

by Dan Talbot | Aug 19, 2021 | Collection, Projects

Some time ago, actually, a long time ago, I wrote a piece about a race car intended to hit the red clay pan of Lake Perkolilli that was under construction by my friend Graeme. In the story I promised to revisit the car when it was finished. I didn’t. Let me finish it now and also introduce the next car under construction by Graeme.

Both of these cars are based upon the Ford Model T platform. Graeme loves the Model T with a passion. He is also a qualified mechanic and somewhat of an amateur engineer. Add a dash of artistic flair and you can begin to appreciate the skills this man possesses.

So, back to Graeme’s black T. Graeme’s racer was created in the format known as a “Gow Job,” which apparently comes from “gowed up” (Hiedrick, 2014). These home-built speedsters typically started with a Ford 4-cylinder, presumedly due to the ubiquity of the humble Model T. Hiedrick states these engines had a top speed of 55 to 60 miles per hour, which, as the owner of a veteran 4-cylinder Ford, I find rather ambitious. “To increase this top limit, a gow job mechanic would remove anything unnecessary – fenders, bumpers, windows – to improve the power to weight ratio” (ibid).

Last time we saw the black gow it was devoid of wheels and paint. To recap, the racer is powered by a 3-litre, 4 cylinder, mounted on an original Model T chassis that has been lowered some 10 inches. As is often the case with projects from the distant past, Graeme only had bits and pieces of a body. For the pieces he was missing Graeme used his unique CAD (cardboard aided design) templates to first fashion the required part and fit it against the body before creating the panel in metal. All the bright metal in the accompanying photographs has been fashion by Graeme, by hand.

Here’s one he prepared earlier. Another journalist referred to this car as a “Gow Job” which sent me searching for the meaning of such a term.

Beautiful from any angle.

Naturally, the black gow was finished and triumphed at the 2019 Perkolilli event. That event was covered by me in another publication (because they pay more than I do). It can be viewed here. The racer clocked a top speed of 126 km/h on the chopped up red dirt. Not bad for an engine built in 1925 with 20 horsepower. Graeme is going for broke now with an engine which he is hoping will yield a top speed of 160 km/h – which is the old ton, or 100 miles per hour. The ton was quite elusive in the nineteen twenties so racers had to be resourceful to break it, frequently breaking the engine and/or car in the process. In true racer endeavour, Graeme has built an engine which I suspect will give the ton a good nudge. More about that engine later, for now we shall look at where the 2019 Perk engine is going. Enter Green T.

The narrow Aston body fits the Model T chassis quite nicely, although the cockpit remains a little cramped at this point. Note Graeme’s cardboard aided design.

Boat-tail rear.

Green T started out, as the name suggests, as a Model T. Actually, a conglomeration of Model T parts Graeme has collected over the past few decades. A glace around his very well organised shed suggests he could build several more. As alluded to above, the race-proven engine will be mounted into one Graham’s expertly fabricated, lowered and modified race chassis. It will then be fitted with an Aston Martin body, more particularly a body from an Aston Martin. It is unlikely the body was actually made in the Aston Martin factory but it has seen service on a very special Aston Martin racing car that was brought to Australia for the 1928 Australian Grand Prix.

The Aston was a lithe, alloy-bodied, open wheeler GP car from 1922 or 23 (it’s not exactly clear). It was powered by supercharged 1486 cc side valve engine of Aston Martin’s own design. Incidentally, Lionel Martin’s partner in their fledgeling automotive manufacturing business was Robert Bamford. The name Aston Martin comes from a celebration of the success Lionel Martin enjoyed at the Aston Clinton Hill Climb in Buckinghamshire, England driving a car of his and Bamford’s creation.

The men went into production and began selling small numbers of their cars, possibly as few as 55, three of which are known to have been brought to Australia. One of the three cars was purchased by Mr John Goodall and evidently had a successful history of racing in Australia, including being driven by Mr Goodall on the first Australian Grand Prix, a 100-mile event at the Phillip Island circuit in Victoria in 1928. The car failed to finish in ’28 event but was entered again in 1929 and 1930, finishing third in the latter event, which by that time had grown to 200 miles.

In 1977 the car was purchased from the Goodall family by Mr Lance Dixon. It turned out much of the alloy components of the engine had been melted down for armaments during World War II. However, another engine, from one of the original three cars imported back in ’27, was located by Mr Dixon, powering, of all things – a boat. The engine was fitted to the remnants of the Goodall car and a body was remanufactured out of steel. The small race car remained with Mr Dixon up until 1982 when it was purchased by Mr Peter Briggs for display in the York Motor Museum and, later, the Fremantle Motor Museum.

Under Mr Briggs’ ownership the car under went a full restoration which included a new aluminium body. The builder of the body flew from Perth to the UK with the sole purpose to measure and record one of the original GP Astons to ensure authenticity of the reconstruction.

Peter Briggs’ Aston Martin after it had been returned the original style of the all aluminium body. Photograph by Mr Holger Lubotzki.

The steel body was stored first behind the York Motor Museum before being moved to the Veteran Car Club of Western Australia parts store in the Perth suburb of Wattle Grove. And that’s where Graeme found it. So, to take stock, we have enough parts to build another Perkolilli racing Model T, a body from a famous Australian racing Aston Martin and a very talented mechanic slash engineer. Some twelve months ago, Graeme began construction of Green T, the name paying homage to another famous racing Aston known as “Green Pea.”

With the same owner now since 1958, this well-known 1922 Aston Martin is affectionately known as Green Pea. It is of similar pedigree to the car imported by John Goodall in 1927.

The Aston body T has been cut, tucked and moulded into the what is clearly going to be a very special race car. To be honest, the body looked a bit odd on the Aston Martin chassis. It sat up high, was cramped and carried odd lines that departed somewhat from the racing stance of the original Aston Martin machines. Graeme has widened the car and remanufactured the cowl, both raising and lengthening it. The result is two humans can now comfortably sit in the car (including yours truly who is 6’ 4” in the old scale). These mods have added style and flair befitting a car of the era.

The Aston competes at the York Flying 50 C1982, prior to its aluminium upgrade. Note how high the body sits and the way the passenger is skewed to the right. Graeme has overcome both of these issues.

Again, the Aston still with the steel body fitted.

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.

Widened in the beam, Green T will now comfortably seat two full size human beings.

by Dan Talbot | Mar 16, 2021 | Collection, Events, Racing

“Norton owners like nothing better than pulling their engines apart on Sunday afternoons (Donald Heather Man. Dir. AMC 1954-60).

With the greatest respect to Donald, some Norton owners actually prefer to be riding their machines, such as those who gathered in Donnybrook, Western Australia over the 13th and 14th of March, 2021. In excess of 40 Norton owners assembled for two days of riding, nattering about and admiring Norton motorcycles. Not just any Nortons mind you, this was a gathering of Norton motorcycles with only one cylinder. These folk think nothing better than riding their motorcycles on a Sunday afternoon however, given the last Norton single was manufactured in 1964, there’s plenty of afternoons spent pulling engines apart.

Donald Heather’s utterances were nothing more than motherhood statements designed to appease investors who, in 1960, were growing nervous with the lack of future direction the exhibited by the company. Rumours of unreliable and fallible machines were quelled by Heather as he fought to hang onto his lucrative position. The remedy proved to be a series of twin cylinder machines and, presumedly, the appointment of a more passionate and dedicated executive who would remain faithful to Norton’s heritage. However, by then, it was too little, too late. Norton twins were a fine machine but the company only managed to hang by its bootstraps. Gone was the racing heritage and successes that defined Norton’s early years.

1910 was Norton’s second year with his own engine. Only seven of these machines are known to exist in the world, here are two of the seven at the same event in Donnybrook, Western Australia.

Norton Motorcycles was established in 1898 by James Lansdowne Norton. Norton was a gifted engineer but a poor businessman and the company fell into receivership early in its life. This would signal the future for a manufacturer who was more concerned with performance and reliability than returning dividends for shareholders. Competing with the liquidity of Norton Motorcycles, was James Norton’s health. He fell ill as a young man and was left with a malady of premature aging, earning the young engineer the nick-name “Pa.”

Pa Norton was only 55 years of age when he passed away and sadly did not live long enough to witness the legacy of his creation – namely the most successful single cylinder motorcycle of all time. I can hear Ducati riders spitting their Chianti back into glasses everywhere. Whether, or not, Norton is the greatest motorcycle of all time is an argument best left for campfires, dining room tables and Christmas day punch-ups with the brother-in-law. What can’t be disputed is single cylinder Nortons are achingly beautiful motorcycles with performance to match. It’s no accident Norton dominated racing across the UK and Europe for the first half of the twentieth century. Ten Senior TT wins between 1920 and 1939 and 78 out of 92 Grand Prix races are impressive statistics in anyone’s language (including Italian).

In 1924 Pa Norton, suffering advanced cancer, was wheeled up to the main straight of the Isle of Man TT circuit to witness his motorcycles take out two TT trophies that year. Pa received the great chequered flag of life on 21 April 1925 and has been venerated ever since. By many people, including me. My trials and tribulations are well documented on this site and elsewhere, but, still I remain a faithful follower of the brand.

Muz and Rocket, two Norton enthusiasts the author is honoured to call friends.

This brings us neatly to the inaugural Norton Singles Run, hosted by the Indian Harley Club of Bunbury, Western Australia. The run, hatched by Norton enthusiasts Murray, Peter and Kelvin, was scheduled to take place in February was postponed when WA went into a Covid-enforced lock-down, throwing plans into disarray. Had it not been for the Covid factor one would expect many more motorcycles, however, by any measure, the inaugural event was a huge success. The line-up of machines on display was breathtaking. ‘Line-up’ is probably the wrong word, getting this mod to form anything resembling an orderly assembly simply for a photograph was not on the agenda. These blokes wanted to ride Nortons, talk Nortons and look at Nortons. Consider, there are seven 1910 Norton motorcycles know to currently exist in world. Two of them were present at the Norton Singles Run. 1910 was Pa’s second year of production with his own engines. Up until this time he had been using proprietary units from Swiz and French manufacturers. It was a Peugeot V-twin engine that powered Norton to victory in the first ever Isle of Man TT races in 1907. That was the last time Pa Norton would dabble in twins, as far as he was concerned future victories lie in the simplicity of singles. The rest is, as they say, history.

Another profile of the pair of 1910 Nortons. This one by Alan Wells.

One of the lovely ES2 Nortons that were in attendance at the inaugural Norton Singles Run in Donnybrook, Western Australia. Photograph by Alan Wells.

Another ES 2, this one from 1935. Pic by Alan Wells.

A line up of achingly beautiful Norton motorcycles. These ones are from 1924 to 1926.

Event organiser, Kelvin, wasn’t letting crutches prevent him participating in the ride.

Greg on his stunning ES2.

The 500cc 1910 Norton was getting along at a fair clip. Here she has just climbed a hill that would have a modern motorcycle looking for a lower gear – which is not an option for Andrew, he only has one.

The South West of Western Australia provided the ideal location to get about on vintage and veteran Norton motorcycles.

Manx silver, as far as the eye can see.

Saturday lunch stop was the Wild Bull Brewery in Ferguson Valley, Western Australia. A highly recommended venue.

Event organizer Murray on his 1929 CSI Norton 500, photograph by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography.

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.

Early days of fitting the body to Green T.