by Dan Talbot | Nov 9, 2020 | Events

The Albany Vintage and Classic Motorcycle Club have staged another fabulous event.

When my wife began looking for a classic motorcycle to replace her SR 500 Yamaha she had a couple of criteria. It had to be eligible for classic hill climb competition and, importantly, it had to have an electric start. The SR was fine in the former category but with no electric leg it proved to be difficult for her to start so we ended up moving it on and purchasing her a 1987 GB 500 Honda. This machine uses the XR engine so it’s virtually indestructible and it starts at the press of a button. Catherine was all set, except the first event was destined to rain on her parade, both literally and metaphorically.

The little GB 500 is a tidy machine and starts at the press of a button, but, sadly, too new to compete in the Albany Hill Climb.

When it came time to fill in the entry form for the Albany Vintage Motorcycle Hill Climb, it became apparent the cut-off was 1980. Anything made after that year was out. Being made in ’79 the little SR would have been allowed, indeed, we had entered it in 2019, but the Honda was definitely excluded. With the SR off enjoying life with a new owner, I suggested Catherine compete on the Thunderbird. It was not entirely alien to her, she had ridden the bike and was, by all accounts, competent on the strikingly beautiful motorcycle. She wasn’t happy but agreed I should fill in the application with her on the ‘Bird.

Catherine happy at last to be on our strikingly beautiful Triumph Thunderbird.

2019 had not been a good year for us at the Albany Hillclimb. We couldn’t get the SR to run properly so it was loaded onto the trailer without firing a shot in anger. I on the other hand, did get a run at the hill. I was on my Triumph Triton which has a one down/three up gear-change patter. The Vincent, on which I had been spending most of my time lading up to the event, is one up/three down. On the first go up the hill on the Triton, instead of changing up (like a Triumph should), I changed down – like a Vincent does. The result was a destroyed gearbox.

The gearbox in the Triton required a full rebuild thanks to some errant shifting on my behalf in the 2019 event.

Back to this year. By the time the hill climb weekend came around, Catherine hadn’t even sat on the Thunderbird and it had been perhaps two years since she had ridden it. She had barely ridden her ‘new’ Honda but she assured me she would get some practise on the hill at Albany the day before the event. We drove the 400 kilometres to Albany in beautiful, warm weather and arrived in the seaside town on the Western Australia South coast in the late afternoon. We unloaded the Thunderbird and the Vincent and started them briefly before making them secure for the night (I do this with a few reassuring words).

We were staying at Middleton Beach, near the base of hill climb circuit, so on Saturday morning I opted to take Catherine up the hill on the way to the show and shine event in the Albany CBD. I took off up the hill like a scalded cat and pulled in at the top to wait for the wife. And waited … and waited. Eventually she came puttering up the hill at a snail pace. The Thunderbird was clearly a bit crook but we made it into town. Getting off the Triumph Catherine said, ‘this thing handles like a bag of spuds.’ Make of that what you will but, sure, it’s not as svelte and tight as the little GB which it gave 30-something years away to, but at least by that time the engine was running a bit better. It may have been stale fuel or a blockage but after I topped the tank up with some clean, new petrol the ‘Bird ran sweet. The Thunderbird really has a lovely engine. Everything else in the shed seems angry by comparison.

After a couple of hours Catherine was completely at ease with competing on the Thunderbird. Here she gets some reassuring words of wisdom from WA and UK speedway Ace Rod Chessell. Photo by John McKinnon.

By the end of Saturday morning, having received so many compliments for her choice of machine, Catherine was beginning to feel quite chuffed about being on the Triumph. Granted, I had to kick it every time she needed to get the engine running and, granted, the brakes are merely suggestions for washing off speed, but Catherine soon reacquainted herself with the bike and even managed to get it up the hill in a reasonable time. After the practise runs, and satisfied she knew what she was doing, Catherine and I retired to a bar from which I could drink beer and feast my eyes on two of the most handsome machines in all of motorcycledom. All in all, our Saturday was most enjoyable. The Vincent, the Triumph, the wife and I were in Albany – and we meant business. That night it rained.

Our first couple of runs on the hill were on a wet track, however, by mid-morning the roads were dry and our speeds lifted – which doesn’t help where you’re running for consistency.

I woke at 4.00 am with the rain tumbling down and lay there listening to it as night gave way to a murky, grey loom. This is not surprising. In the local, Nyungar, dialect, Albany means ‘Place of Rain.’ Tourist brouchures promote the area as the “Rainbow Coast” and with an average of 177 rainy days per year we didn’t stand a chance. We trundled off down wet streets spraying my hitherto gleaming alloy engines with a fine mist of pure rain-water and road grime. I was feeling pretty glum as I was sure the event would be cancelled, but no, we would ride: rain, hail or shine. Gentlemen, start your engines. And, in my case, start your wife’s engine too.

We had two runs up the hill to set what would be our nominated time. The aim of the event was then to do three runs up the hill all at the same speed as the elected time, with points lost for going over or under the nominated time. Catherine picked 76 seconds and I picked 48 seconds. Our two dial-in runs were made on wet roads but by the time we lined up for our timed runs, the rain had stopped and the roads were drying out.

The Albany Vintage Motorcycle Club go to great lengths to host their signature hillclimb event. Injuries, crashing and irresponsible behaviour would jeopardise the future running of the event so it came as some relief as the weather turned for the best. It also meant I could give my 1000 cc v-twin a bit more of a handful going up the hill.

To say the Vinnie is loud would be an understatement. Being lined up together was both comforting and burdensome for my wife. She knew she had nothing to prove but she wanted to get away cleanly. The only way should could do this was to allow a second or for me to get away and so she could hear the tone of the Triumph and set about getting it off the line, which she did quite nicely on all three runs, pegging the little 650 to the stop in the first couple of gears she managed to come within .6 of a second on all three runs, however, they were all three seconds below her nominated time. My spread was over 2.5 seconds and two below my nominated time, so I was well out of the running. That said, I had a blast taking the big twin by the hill at full tilt. Best of all, no motorcycles were harmed in the making of these times.

This young man was obviously taken with the stunning beauty of the Vincent Black Shadow.

They don’t call him “Rocket Rod” for nothing. Rod Chessell powers from the line on the JAP special alongside his former speedway adversary Bob O’Leary. Two legends of the sport. Photo by John McKinnon.

Bob Wittingstall’s stunning 1913 Sears on display at the Show and Shine, being guarded by his friend Kelvin.

Not quite the Battle of the Little Bighorn but Indians were prominent at Saturday’s Show and Shine and in the hill climb on Sunday.

Brian Cartwright on his ’53 Vincent sidecar.

Murray with his 1950 pre-unit Triumph outfit. Photo by John McKinnon.

Bob Rees was back in the saddle after suffering a motorcycle crash in Africa last year that left him with critical injuries. Photo by John McKinnon.

Will Turnbull on his 1960 Triumph Bonneville lines up against Tom Constant, AKA the Toad, riding the ’71 Moto Morini 125.

Bob Wittingstall with his Brough Superior SS80.

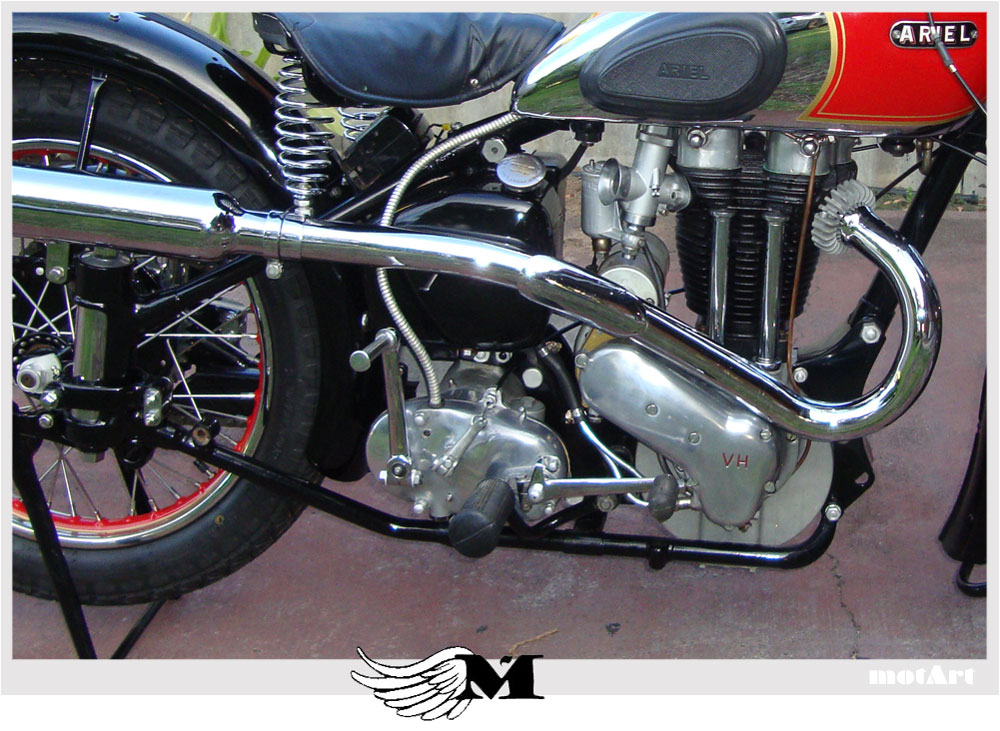

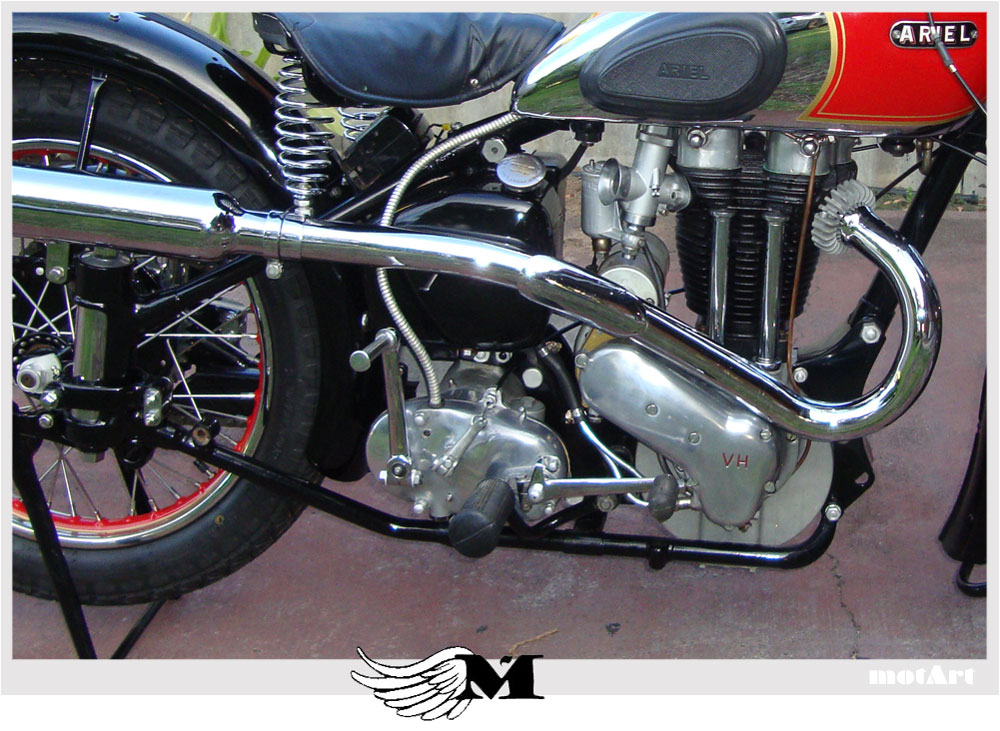

Readers of the Motorshed Cafe will know of our attraction to Ariel motorcycles.

Michael Busby sits astride his late father’s 1956 M50 Norton 350 restored by us here at the Motorshed (see the story elsewhere on this site). It was Chris’ dream to take the Norton to Albany but sadly he did not get the opportunity. His family honoured that dream.

by Dan Talbot | Apr 5, 2020 | Events

This week I was lucky enough to experience my first ride on an Ariel Square 4. These unique machines are quirky, relatively powerful and highly collectable. It was a joy to ride. The motorcycle that I rode was part of a deceased estate which consisted of some 12 operational motorcycles and tonnes of parts, certainly enough to build another 12 machines. As soon as I walked into the shed and saw the bikes and spares laid out, I said, “this must be Ernie Serles’ collection.” As I said those words, it stuck me, with this being a deceased estate, Ernie had passed away. Until that moment I was unaware of Ernie’s passing.

Ernie had been a great help to me when I first built my Ariel and sidecar, most notably when I had major gearbox failure. The following excerpt from Rebuilding the Ariel describes the ecstasy and agony of vintage motorcycle ownership. The excerpt takes up soon after my 1951 Ariel Red Hunter and Dusting sidecar hit the roads for the first time.

This is how we rolled in the mid to late nineties. Evidently, by the time this picture was taken, Emily had graduated to a proper helmet, whereas Molly was still young enough to get away with her bicycle stack hat.

The outfit was finished off and licensed just in time for the annual Biker’s Limited, Perth Toy Run. This would be our maiden voyage. The toy run consisted of a ride of about 20 kilometres from the Southern Perth suburb of Applecross down the Kwinana Freeway into the city. Back then the toy run attracted upwards of 10,000 people.

I had often participated in the Toy Run on my road bikes, way back to the early days of the toy run, when I had my first Harley. On this day I put the kids in the sidecar and off we went. They looked so cute rocking around in the aptly named ‘boat.’ Emily and Molly were both under six years of age and therefore were excluded from wearing full crash helmets. They were allowed to get by with their lightweight bicycle stack hats.

As expected, thousands of bikes turned out for the Toy Run however, many more thousands of spectators lined the route to watch the procession. Sidecars were few, add the two kids in a vintage machine and all of a sudden the whole world seemed to be hooting, waving and hollering at my kids. The ride to the start of the Toy Run was mechanically uneventful, which was a relief as this predated mobile telephones and if, for some reason, the bike stopped, contingencies were few.

M is for Motart. Soon after my Ariel Red Hunter restoration was finished it was featured in the highly exclusive Motart Journal operated by Mr Frank Charriaut. https://themotart.blogspot.com/

Soon after the start of the ride, we had not travelled too far before a police car hailed us to a stop. I was both curious and apprehensive, what did these guys want? Even though I was a detective I still had a fair knowledge of the Road Traffic Code and I felt sure my kids did not need full crash helmets as the heavy appendage could do more harm than good on frail young necks? Aside from that slightly grey area, I didn’t believe I was transgressing any laws.

The Traffic Cop came running up to me clutching a piece of my bike, ‘she’s falling apart on you mate,’ he said as he handed back goodness knows what. I took the wayward piece of hardware with relief. I probably out-ranked the traffic cop but a brush with the law is still a brush with the law! That sounds a little odd but, back in those days, detectives and traffic cops had quite a begrudging respect for each other’s role. Anyway, the piece of motorcycle was dumped into the boat with the kids and we went on with the business of delivering toys to the needy.

We continued on into the city and slowed to the inevitable crawl for the last couple of kilometres. By now, the oil in my engine had thinned to the consistency of water and was seeping through every gasket in the engine. The hot oil running over the barrel gave the impression to anyone nearby that the bike was on fire as smoke rose all about me. Sure there were oil leaks but what couldn’t be fixed or plugged could be passed off as another British motorcycle idiosyncrasy. I wasn’t too concerned, or at least I attempted to portray a nonchalance that made it appear I wasn’t concerned. We rumbled into the city and my children deposited their toys for the kids who were too poor to be visited by Santa – a tough subject that one.

After the Toy Run I dropped the little ones at my mother’s house in nearby Victoria Park and continued on home with an empty chair. All in all, I felt pretty chuffed with myself. It had been a good run and the bike performed well but, most of all, my plan to share the joys of motorcycling with my children had come to fruition. The kids had a ball and I was pleased everything went so well. Now that my girls have grown up, it is times like these that one reflects upon as highlights along the road to raising children. Simple pleasures.

Well, maybe not so simple. It had taken lots of time and money, commodities that were both in short supply around the Talbot household back then, to get to this stage. Lots of trial and error, lots of skinned knuckles, lost temper and cursing as I bumbled my way through tasks hitherto unknown to me. But, in the end, I had turned out a quite remarkable piece of motoring history, I was very pleased with myself. Then, all of a sudden, the bike ground to a stop and the big cheesy grin fell from my face. I was only two kilometres from home, a situation for which I should have been extremely grateful because, as it turned out, I would be walking the rest of the way.

I couldn’t tell what was wrong with the bike but knew for sure it wasn’t good. I couldn’t move the gear lever and the only way I could get the bike to move was with the clutch drawn in. What followed was a two-kilometre push home. It was hard work and, as I was trying to avoid using the road, I stumbled forward keeping as far left as I could. This led to disaster number two.

About halfway home I banged the sidecar mudguard fair into a lamp-post, kinking the metalwork that had been lovingly hand-painted by me using lots of rubbing back and building up with several layers of spray-pack paint. It sounds odd, but with lots of work I actually turned the guard into a splendid addition to the outfit. Now it was scratched, bent and buckled and I was cranky. I was really starting to think ‘are vintage bikes really worth the trouble?’

Despite arriving home mid-afternoon, dehydrated, sunburnt and exhausted, I immediately set about removing the seized gearbox. As tired as I was, ripping the gearbox out sitting on the garage floor, from memory, went quite well. It was the first time I had done such a thing so I was kind of pleased to finally lift the gearbox out of the frame just as it was getting dark. What a day it had been.

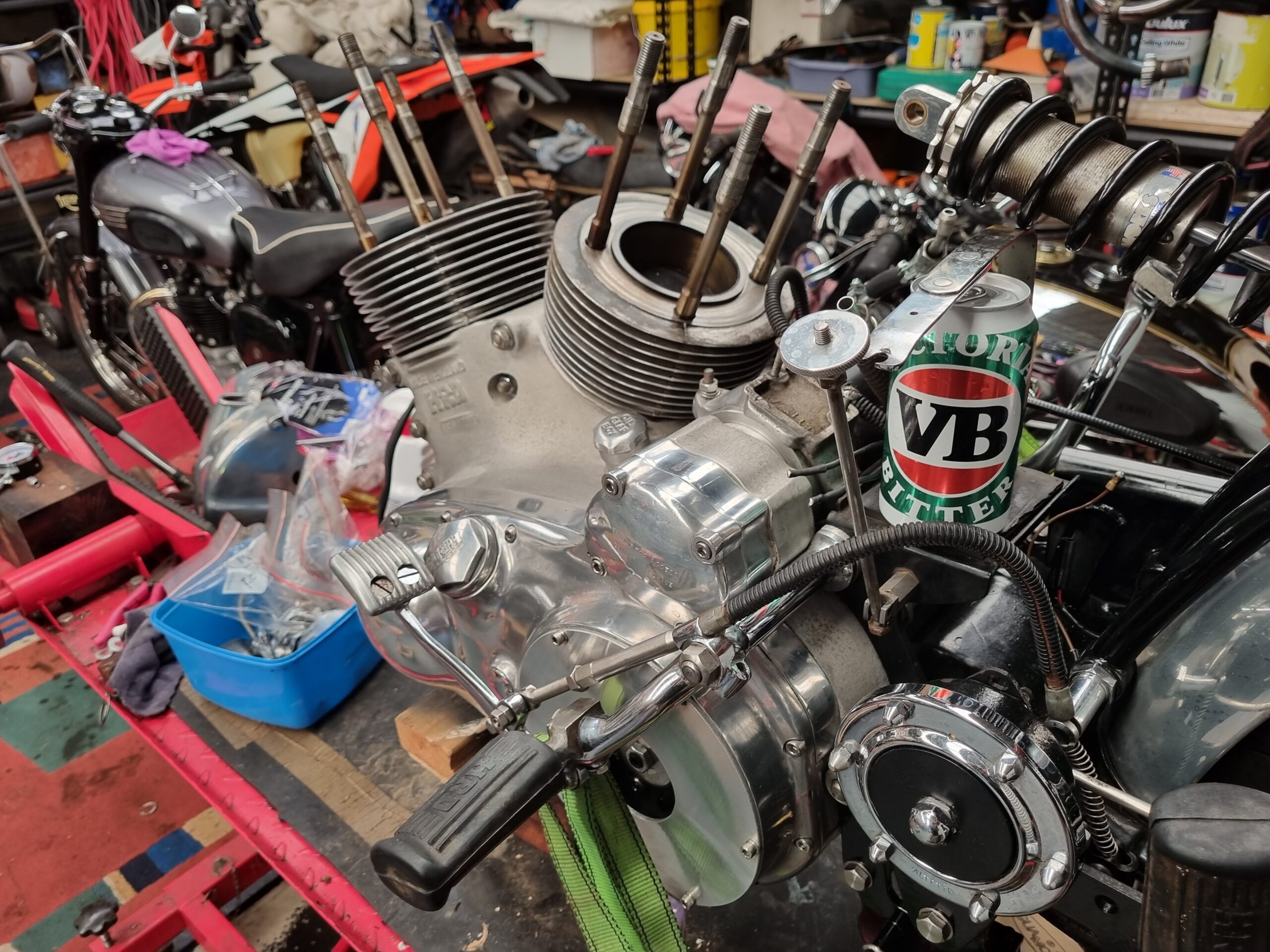

The Ariel gearbox is ordinarily a sturdy piece of equipment but I managed to seize it.

Following the seizure, with the gearbox out, I took it off to a fellow from the Vintage Motorcycle Club who lives and breathes Ariels. At that time, Earn had a large shed at the back of his Bentley house. It was chock full of Ariels and Ariel parts. Being December, it was also unbelievably hot inside Ernie’s shed. As soon as I handed the gearbox over he was off down to the workbench, whereupon he secured it in the vice and got to work. I stood silently alongside Ernie as he beavered away on my gearbox, for as long as I could bear the heat, then blurted out, ‘umm, Ern, I’m actually on my lunch break and really need to get back off to the office.’

Ernie waved me off without lifting his head, I made my way back outside and found it was almost a relief to be outside in the hot December sun. Ernie rang me a few hours later to advise he had located the problem. It was an offending brass bush that had a distinctive home-made quality about it (in fact, as it turned out, a lot of things on the Ariel had a shoddy, home-made quality). Evidently, the bush did not have sufficient journal for oil to flow and, with the added load of a sidecar, the bush got hot, expanded and locked the shaft. A $5.00 replacement was all that was needed.

When I went to pick the gearbox up, Ernie had left instruction with his wife that he wanted $5.00 for his work, and $5.00 for the bush. Naturally I left much more than that, amidst protestations that is was far too much. 25 years later and the gearbox still works as good as new.

Ernie’s ’54 Ariel Red Hunter sits alongside his ’56 Square 4. Two highly desirable and collectible motorcycles.

The late Ernie Serle’s 1956 Ariel Square 4. The old bike is in tip-top condition, starts first or second kick and runs like a swiss watch. A truly remarkable machine.

I took this photograph of a Square 4 outfit at the annual Indian Harley Club 2 Day Rally in 2018. Note this is the earlier, Mk 1, machine. The exhaust exits the front of the head, unlike the Mk 2 (above) which has four pipes (two each side) which was said to aid cooling.

by Dan Talbot | Dec 7, 2019 | Collection, Projects

When we left off with the last instalment, the little Norton was parted out here, there and everywhere. Readers and interested parties will be happy to know most of those parts have been renewed and, if not back together, they’re at least back in the shed. One such ‘part’ is the engine.

For a 350 cc machine, the engine in the little Norton is a substantial lump of iron and alloy. This is understandable as essentially the engine started out as a 500, only the internals are different. In fact, the whole bike is basically a 500 ES2, albeit with 350cc. This actually makes it quite rare. By the mid nineteen-fifties young men in the UK were craving larger capacity machines and would overlook the M50 in favour of its big brother. Many of the 350 cc bikes that were purchased had the single cylinder engine taken out in favour of a larger twin, such as that found in the Motor Shed Triton.

The 350 cc Norton single.

You’ll recall the story of the Triton, a parts bin special created by throwing a Triumph twin engine in a Norton frame? The featherbed frame, which is discussed at length in the Triton story, was a huge success for Norton. The twin down-tube, cradle style frame was to become the signature to the Norton motorcycle racing effort. They had long proven they had the best engines, the featherbed frames simply helped the company assert their racing credibilities and maintain their dominance in the two-wheeled, racing world (I’m sure that’s poke a hornet’s nest so hit me with your best shot :).

Elsewhere in the range, the single down-tube frames were left for commuters, tourers and those wishing to fit sidecars – which were a big thing in Britain as the country recovered post-war. The Buz Norton is of the second group, not a risk of losing it’s engine older, single down-tube, ‘pre-featherbed’ frame. I say this in parenthesis because they were never actually referred to as pre-featherbed,’ this is a retonym used by various people and groups, such as parts suppliers – some of whom I’ve become intimately acquainted with.

The fuel tank, single down-tube frame and engine before restoration. Note the sidecar lugs on the frame (visible near each end of the fuel tank).

Andover Norton has been the preferred parts supplier. They are very fast in getting gear out to Australia but as far as the singles go, parts are limited. I’ve also found the catalogue is not too accurate, which has resulted in me receiving an axle that doesn’t fit. “And where’s the original axle?” I hear out there on the ether. Being a basket case, which by definition is a jumble of bits and pieces, some things have inevitable gone missing. The rear axle being one such item.

One of the hazards of international purchases, they don’t always fit.

Speaking of axles, we have two freshly build wheels waiting to be fixed to the machine. They are brand-new, stainless rims and spokes laced to freshly vapour-blasted hubs. They look fabulous. Shiny, but not too so. The modern rims and spokes, together with the original, sturdy hubs have resulted in some tidy rolling stock. It will be a long time before these wheels wear out.

The new front wheel. It will be a long time before this one ever wears out.

Elsewhere on the bike, having done the math, it was economically and mechanically sound to dispense with all the broken and rusty clutch parts in favour of the beautifully crafted Bob Newby belt drive. These things are a work of art that would ordinarily over-capitalise such a machine as the M50 but there was simple nothing that could be salvaged from the original clutch so picking up a Newby belt drive and clutch set up has saved money, added reliability to the bike and lessens the likelihood of oil escaping the primary, because there’s simply none in there.

The Newby belt drive. A work of art that, sadly, won’t be seen.

The engine is snugged up, back in its rightful place. With vapour blasting shining all the alloy pieces and a lick of pain or plating on the metal components, the engine is looking as good, if not better than new. Plating consist of chrome or cadmium, the former costs a king’s ransom, the latter is not so bad. Like other forms of metallurgy, chrome plating, when done right, is of much higher quality than in the days when the Norton first travelled along the production line, which is what we’re aiming for with the whole bike.

Metalwork prior to cadmium plating.

Metalwork after cad plating.

Engine top end – before.

Engine top end – after.

Chrome-plated items.

The rear guard is back from the painters and is so shiny you could do your hair in the reflection.

by Dan Talbot | Oct 2, 2019 | Collection, Projects

I was recently having a chat on messenger with Mr Fritz Egli himself about Nortons, specifically the modern incarnation of the 961 Commando, such as that which lives in my shed. Suffice to say Fritz is not a fan of the new Norton however I enjoyed tapping into his knowledge base, even if he did insist on telling me how bad he thought the Norton was. Anyway, after I figured we had developed a comfortable rapport, I clumsily steered the conversation towards my “Egli” build. Without another word Fritz left the conversation.

Mr Egli is quoted in Philippe Guyony’s 2016 publication Vincent Motorcycles, The Untold Story since 1946, on the popularity of unauthorized copies of his famous motorcycle frame design, “The were more than six workshops manufacturing and selling unauthorized copies of my frames all over Europe as the genuine ‘Egli-Vincent.’ of course, at first I was upset, but soon I regarded it as a compliment to my design and then I moved on (2016, p.6).”

I’m prompted to rename my project, I’ve been thinking of the Triple T (Taylor, Talbot, Triumph). Comments and suggestions for a name are welcome at the bottom of the page.

In the interests of revision, and for those that are new to this project, Colin Taylor, who has built over 90 Egli-style frames, was tasked with building a frame for me to plonk a T150 Triumph 750 triple engine into. It is my intention to build a mid-seventies, part hot-rod, part superbike, special. An almost unique machine that will go as good as it looks. I say ‘almost unique’ because, as best as I can tell, there is only a handful other Triumph triples living in Egli-style frames that I know of. Indeed, Egli himself is rumoured to have built two frames for Slater Brothers in England to fit triple engines to and authorized the construction of another 12 by specialist frame builders in the UK at Slater’s direction. This was something I was about to discuss with Fritz when he terminated our conversation.

Tapping into online resources I’ve identified at least three Egli-style T150 motorcycles in France, one in Norway and the below pictured machine owned, crashed and burned by Marc Maslin in the UK. Marc’s motorcycle was one of the original Egli authorized copies and therefore comes with the blessing of Fritz himself. Sadly Marc’s bike underwent a Viking funeral (as Marc puts it) and is now resting peacefully in Valhalla.

Marc Maslin’s original Egli Trident T150v. The 850cc Triumph engine was fitted with a lightened and balanced crank, breathed through 30 mm carbs, had a gas-flowed and ported head, lightened and balanced pistons. Upgraded oil pump and enlarged oilways.

At the time of contracting Colin for the build I didn’t actually have a T150 engine but they are certainly easier to come across than the Vincent engine synonymous with the original design. I expected it would be a short time before I located a suitable engine, but, instead, I’ve been locating whole bikes, albeit barn-finds and basket cases. I now have a ‘71 BSA Rocket 3 and a ’74 Triumph T150, neither of which I’m willing to sacrifice to the build we are discussing here. Incidently, the causal relationship between the BSA and Triumph triple engine is a fascinating topic that can be read here.

I also have an assortment of T150 engine cases, crankshafts, heads and other engine parts that I have brokered and bartered for over the past couple of years. To the casual observer it might look like I have enough bits to build three engines but most of it is quite poor quality and certainly won’t withstand the rigors of what I’m intending on building, however it does serve a purpose which will become apparent below.

Over the past few months I’ve been able to amass a few Triumph T150 engine cases and parts.

In August this year my wife and I returned to the UK and our favourite place in the world – the Isle of Man. In travelling to the Isle, we flew into Manchester and boarded a train for the one-hour ride to Liverpool. Sitting at the top of platform 5 in Liverpool, Lime Street Station, was Colin Taylor with my brand-new, nickel-plated, motorcycle frame. After many emails and me sending a not inconsiderable sum of money to Colin in the preceding months, we finally met face to face. I’ve read a lot about Colin and his creations and have seen his photograph numerous times in the motorcycle press so it was quite special meeting the man and being regaled by his jokes and general banter.

The author finally meets the specialist frame builder Colin Taylor – and takes delivery of the newly finished frame for our Triple T special.

I would love to say I was giving Colin my undivided attention but, in truth, I had one eye fixed upon my frame sitting on the floor of a very busy English Liverpool pub, dividing my time between that and chatting to Colin about all things motorcycling. We broke bread and drank Guinness and had a pretty good afternoon before Catherine and I made our way down to the ferry terminal and Colin headed off back to Nottingham (although he is an Englishman, Colin lives and builds his famous frames in Italy. I’ll leave Colin to add his contact details to the bottom of the page for anyone wanting to build a special).

I slung the frame over my shoulder and we set off on foot for the two-kilometre walk to the docks to board our ferry to the Isle. Along the way, a few curious onlookers, recognising a motorcycle frame, asked what machine it was intended for. If the frame sparks this much interest, imagine what the finished bike is going to do.

The frame is packed and ready for the long journey to Australia.

A week later, after an exhausting, 24 hour, non-stop journey from the Isle of Man to Busselton, Western Australia, we finally arrived home. I went straight out into the shed and tried my frame against one of the T150 bottom ends I have stashed there and, guess what, she fits.

So now I have my frame and my T150 donor bike, there’s one small problem. I can’t possibly separate the engine from this bike. This is a matching number, time-capsule from 1974, parting it out is not an option. Phil Irving, the Australian engineer responsible for designing the Vincent V-twin engine, in his 1992 Autobiography wrote, “there were those (including myself) who considered that every new Egli meant one less Vincent (1992, p.514).” I have no doubt many fans of the Triumph T150 would feel the same way. Sure I’ll take the odd part from the T150 but, when this project is done and dusted, that T150 will be the next machine to undergo a full restoration, to be brought back to its former glory. In the meantime: does anyone have a spare T150 engine they don’t need?

Up until now, this bike has been referred to as a ‘donor,’ insofar as the engine was intended as a base for the project. Having now secured the bike and moved it to our shed, this matching number survivor machine is too good to part out for a special and will eventually be returned to the road in original trim.

Despite the rust and dust, this motorcycle has had very little use. It was last registered in Ohio in 1981 and represents a true ‘barn-find.’

by Dan Talbot | Oct 1, 2019 | Collection, Projects

It should come as no surprise to anyone who knows me that throughout my life I’ve had a strong yearning to own a Vincent motorcycle. I’ve come spectacularly close to owning a Vincent about two and a half times but life had other ideas for me (and that’s fine). Vincents have, by and large, remained a figment of desire, the unicorn that was never going show up in my shed. Until now.

A Vincent motorcycle is the classical embodiment of speed and sophistication, a triumph of technical expertise from the golden era of the British motorcycle industry. For decades I have been immersing myself in the literature, both technical and folklore, around these motorcycles. Often I found the dream very nearly outgrew the reality, but dreams often do.

It has long been held Vincent motorcycles were advanced beyond their nineteen forties design but they were created by man, made of metal and alloy and they’re not exactly rare, just very expensive, so, fiscal resources aside, my dream was destined to one day become a reality – I just didn’t expect it would take me forty years! Of course, having been created by man so too can they be improved by man. One man particularly versed in improving the Vincent is Terry Prince.

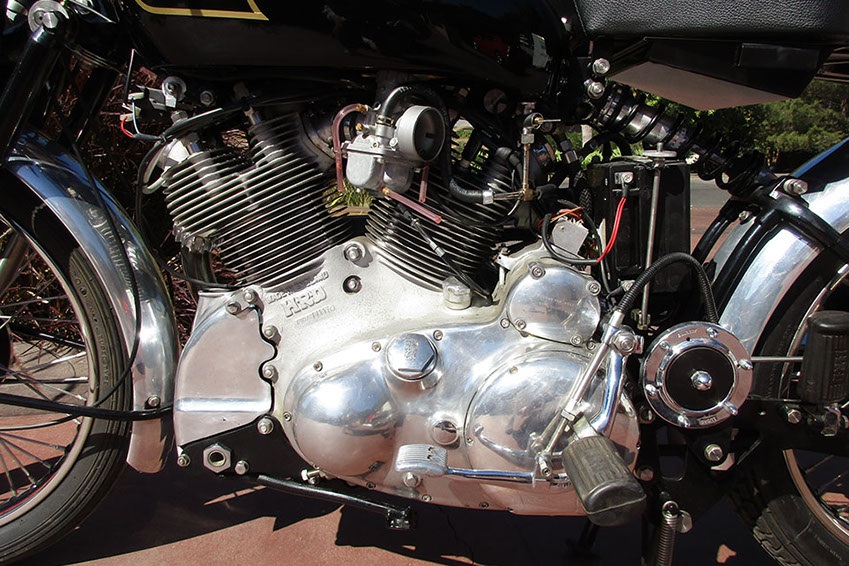

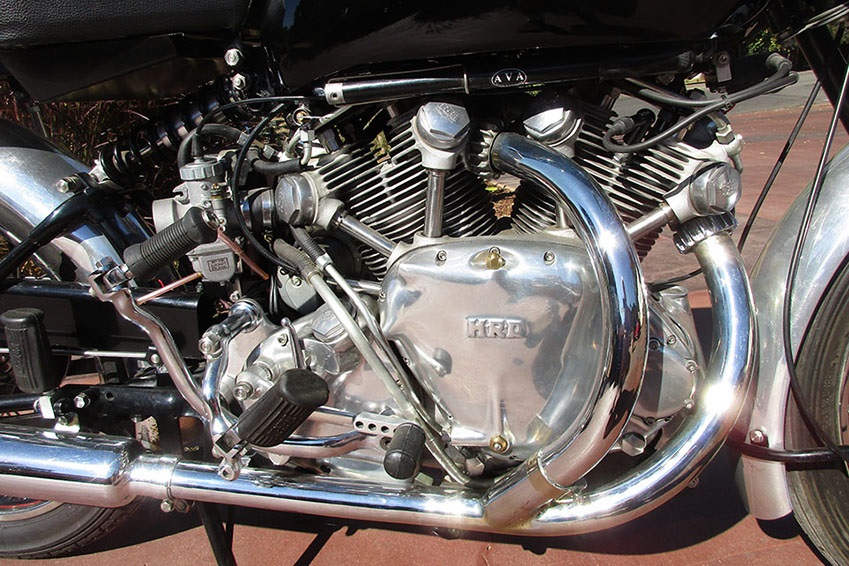

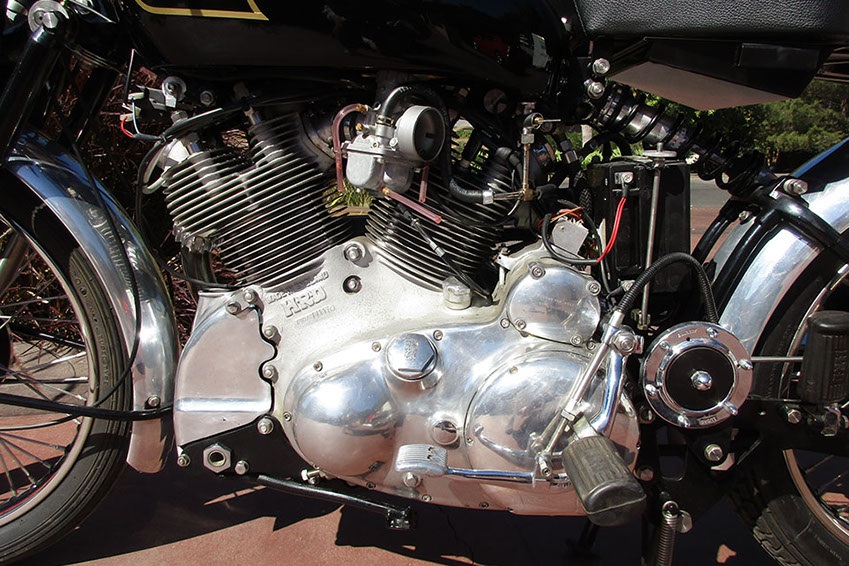

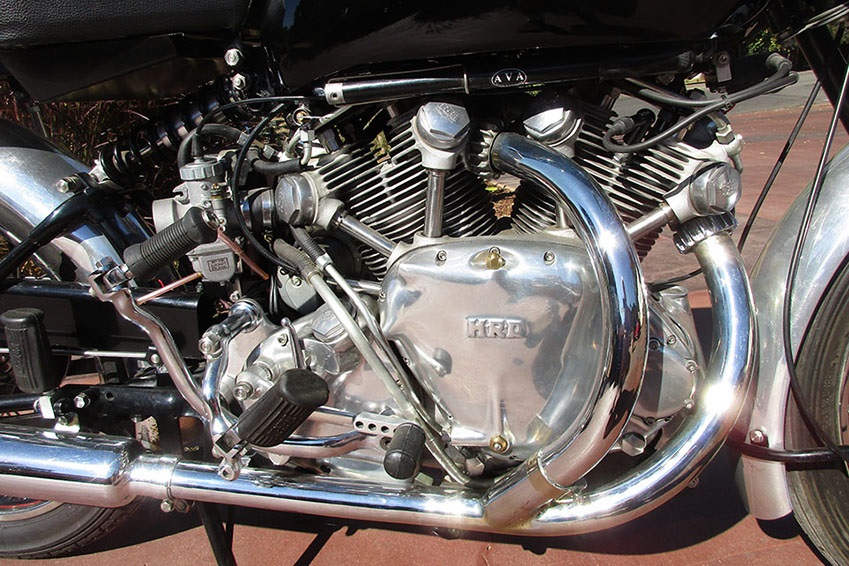

At the heart of the Vincent, indeed the great majority of the bike, is the stonking, huge v-twin engine. One of the most iconic images in in all of motorcycledom.

Throughout the life of the Vincent motorcycle a few names come to the fore, Howard Raymond Davies (HRD), Phillip Vincent, Phillip Irving and Terry Prince. There’s a great many others but those four gentlemen feature prominently in Vincent discourse that I’ve been drawn to over a lifetime of consuming information on the marque. With Terry Prince being the only who is still alive, and therefore still active in Vincent engineering, he is keeper of the Vincent flame. Terry is known around the world as one who will manufacture a complete, Vincent engine, and even the whole motorcycle, using modern engineering and materials.

Terry Prince (far left), has a life-long association with the Vincent marque and is recognized today as one of the most knowledgeable people in the world as an expert of these unique machines. Terry is photographed here at Bonneville Speedway where his 60 year-old motorcycle set a world land speed record in 2010 – with Terry at the controls! Photograph courtesy Terry Prince.

When a 1948 Vincent Rapide popped up on the market laying claim to having been restored by Terry Prince consisting 85% of new parts it well and truly pinged my motorcycle radar. Here was a Vincent that promised a balance between original, precious metal and a road-going, reliable link to the iconic motorcycle. The advertising blurb read, amongst other things, “Prince’s hand is evident all around the bike, starting with the front brake hubs, which contain four-leading-shoe internals. Suspension has been upgraded with modern dampers front and rear. An accessory tread-Down centre-stand eases parking chores. The Shadow 5in. ‘clock’ perched atop the forks is a nice touch. Of course the engine – just overhauled by Prince and breathing though modern carbs.”

The Black Shadow, 150 miles per hour, speedo is a nice touch to my Rapide. Indeed, many Rapides are upgraded with the massive 5 inch instrument.

The 5 inch clock is a massive speedo that has been lifted from Vincent’s own hot-rod, the Black Shadow. Rumour has it people have been booked for speeding by police who have been able the read the speedo from a position slightly astern of an errant Vincent rider. There were some other Shadow touches that added to the desirability of the machine, although, it should be said, a Vincent Rapide in stock trim is a highly desirable machine on its own.

I resolved to call Terry Prince.

Having made the decision to call Terry, I found I was a bit nervous. What if I wasn’t deemed competent to own a Vincent? I had let opportunities of ownership slip through my fingers in the past, maybe the motorcycle gods had already decided I wasn’t eligible to join the ranks of Vincent owners. Or, perhaps it could be fatalism with all the other machines being pushed aside until this one came along. With all the nervousness of a job interview I made the call.

Dave “Bones” McLauchlan racing Terry Prince’s Vincent solo bike. The engine in this machine is producing more than three times the power of its original output! Photograph courtesy Terry Prince.

Within moments of calling Terry Prince I was relaxed and we were chatting like old friends. The more we talked the more I wanted that motorcycle. I learned the bike had been reassembled by Terry from a basket case presented to him along with a Vincent Black Shadow. At the time of building the machine it was Terry’s intention keep it as his personal everyday rider, which reinforced the notion of no expense spared when it came to building the machine with upgraded brakes, suspension, modern carbs and electronic ignition.

At the time of calling Terry two other people had expressed an interest in the bike and one was particularly serious, so serious in fact the bike had been shipped from the US to Melbourne as the prospective purchaser lived in Victoria. How the bike came to be in the US is a long story, but, at the time of my call, it was still sitting in California.

Before the bike was due to leave the US a Black Shadow came up for auction in Australia and purchaser number one was keen to bid on it and Terry was prepared to hold the Rapide pending the outcome of the auction. Evidently he won the auction, with a bid of $AUD160,000, as two days later when I phoned Terry he hadn’t heard from either gentleman and the way was cleared for me to send my deposit to secure the motorcycle. I hurriedly sent off a great chunk of the funds I had set aside for my daughter’s forthcoming wedding (sorry Love).

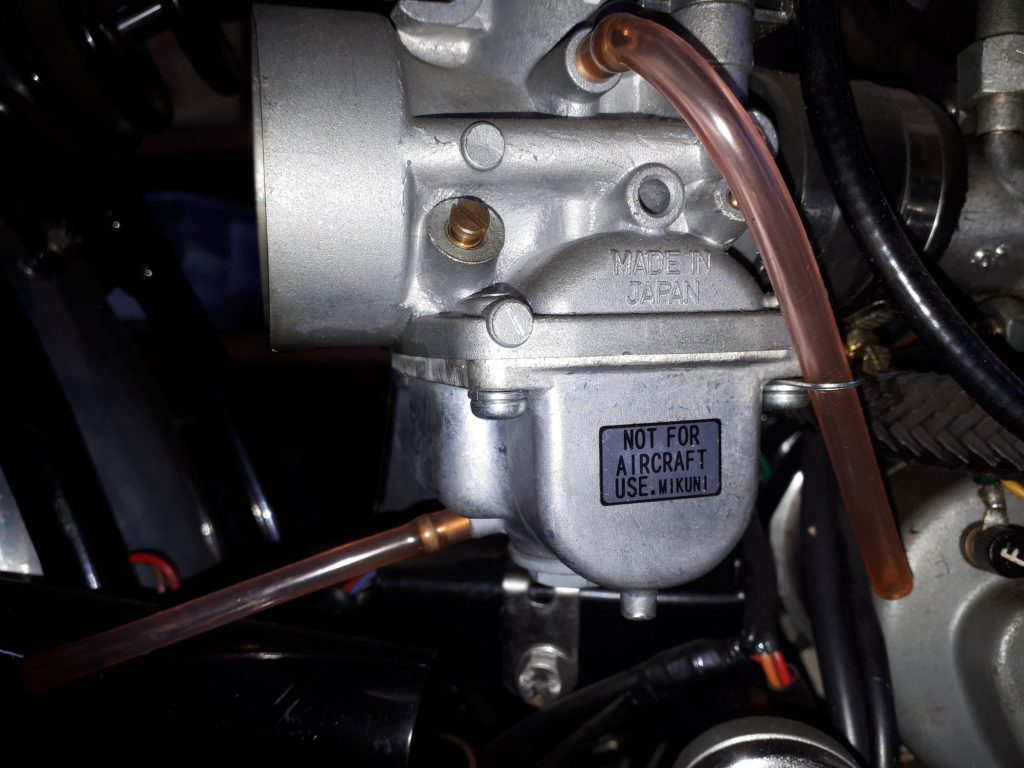

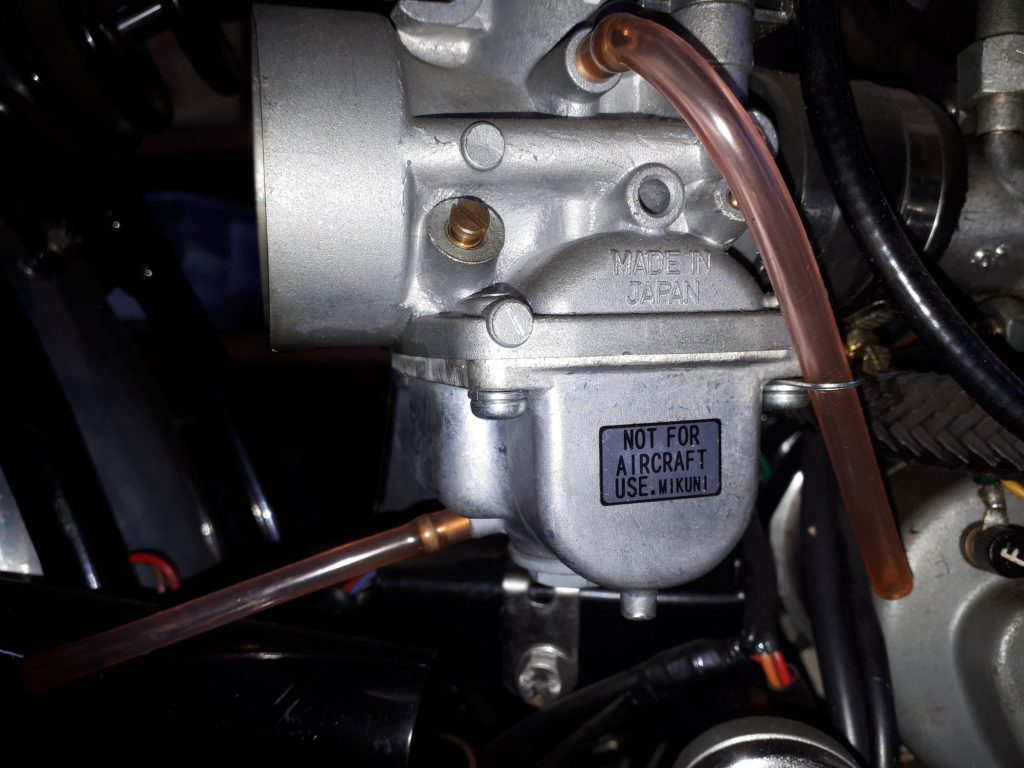

“Not for aircraft use,” probably not for Vincent use either in my book. Mikuni carburettors work well on Vincents, and in my Triton, but having desired a Vincent for over 40 years and pouring over countless machines, photographs and references of these fascinating motorcycles, everytime I look at my Vincent, my eye falls to the Japanese carbs. They will probably be replaced with original Amal items in the very near future.

Sometime later the Vincent was loaded on a ship destined for Melbourne. I waited a few short weeks and as soon as the boat berthed in Melbourne I booked my flights, first to Melbourne to check out the bike and secondly to Sydney to meet the man himself and hand a cheque over.

10 weeks after striking our deal I was standing in front of my Vincent (I still get a pang of excitement when I say ‘my Vincent). She’s a beauty. After two years in the US she’d lost a bit of lustre but I know within a few hours of the bike arriving in my shed she will be looking as good as new. I spent a couple of hours running my eyes and hands over the bike and heard her running. Satisfied with my purchase I set off for Sydney.

A 40-year dream of owning a Vincent motorcycle is a reality.

Arriving at Terry’s forest hideaway I’m met first by Ursala and then Terry comes out to greet me. Again, I’m immediately at ease with this couple who have invited me into their house for the night. After coffee and a chat I was treated to a visit to the workshop. There was four Vincent motorcycles and an at least one complete engine in the workshop. I was particularly intrigued by the engine because it is a new one, made from all new parts. Sadly, the parts don’t simply just bolt together and, out of frustration, it has been sent to Terry to rectify and make usable, causing him a host of frustrations. Had he been on the job from the get-go it would be fine but now Terry is having to go back to bring someone else’s work up to spec. It’s a difficult and costly task which, at the end of the day, will result in someone having spent a lot of money for a replica Vincent engine.

Standing in the workshop, I’m juxtaposed between the old and the new, where items from this century and last are found in the same engine. Terry’s original engine, one he’s owned for close to 65 years, sits in a modern chassis and is reportedly pumping out over three times its original 45 horsepower. That same engine has also seen regular service in Terry’s Land Speed Sidecar – which still holds world records at Bonneville Speedway. This creation is not unlike Bert Munro’s famous Indian, except Terry started with better stock in the Vincent than a clunky, old vintage Indian.

The stock of new parts, heads, barrels, pistons and just about everything that has a thread is tantalising. One of my close calls to Vincent ownership includes me recently bidding on a pair of Vincent crankcases. Two lumps of alloy that were sold for close to $AUD5,000. At the close of the auction I was slightly relieved not to have been the winning bidder, a relief that was even more palpable when I saw the look on Terry’s face as I recounted the story. Suffice to say I would have been up for a lot of money to bring those crankcases up to anything resembling a functional engine.

Anyway, I needn’t worry about that now as I have the genuine article complemented by some modern parts that maintain the authenticity of a 1948 motorcycle in a package that will outlive me, even if I ride it every day for the rest of my life – which is exactly what I plan on doing.