by Dan Talbot | Oct 1, 2019 | Collection, Projects

It should come as no surprise to anyone who knows me that throughout my life I’ve had a strong yearning to own a Vincent motorcycle. I’ve come spectacularly close to owning a Vincent about two and a half times but life had other ideas for me (and that’s fine). Vincents have, by and large, remained a figment of desire, the unicorn that was never going show up in my shed. Until now.

A Vincent motorcycle is the classical embodiment of speed and sophistication, a triumph of technical expertise from the golden era of the British motorcycle industry. For decades I have been immersing myself in the literature, both technical and folklore, around these motorcycles. Often I found the dream very nearly outgrew the reality, but dreams often do.

It has long been held Vincent motorcycles were advanced beyond their nineteen forties design but they were created by man, made of metal and alloy and they’re not exactly rare, just very expensive, so, fiscal resources aside, my dream was destined to one day become a reality – I just didn’t expect it would take me forty years! Of course, having been created by man so too can they be improved by man. One man particularly versed in improving the Vincent is Terry Prince.

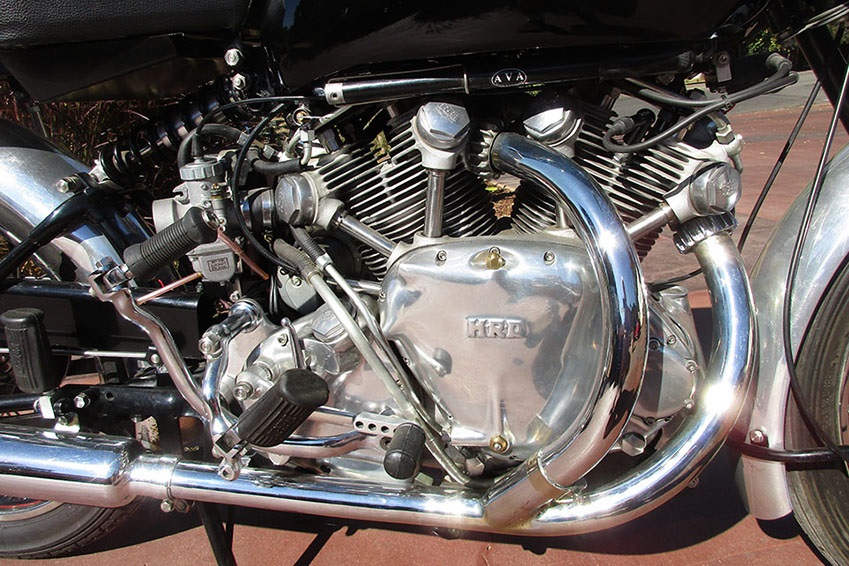

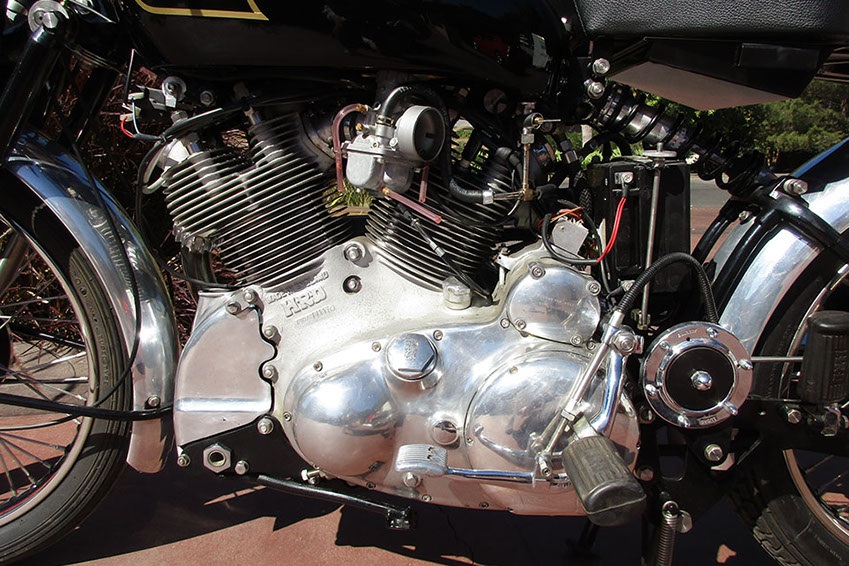

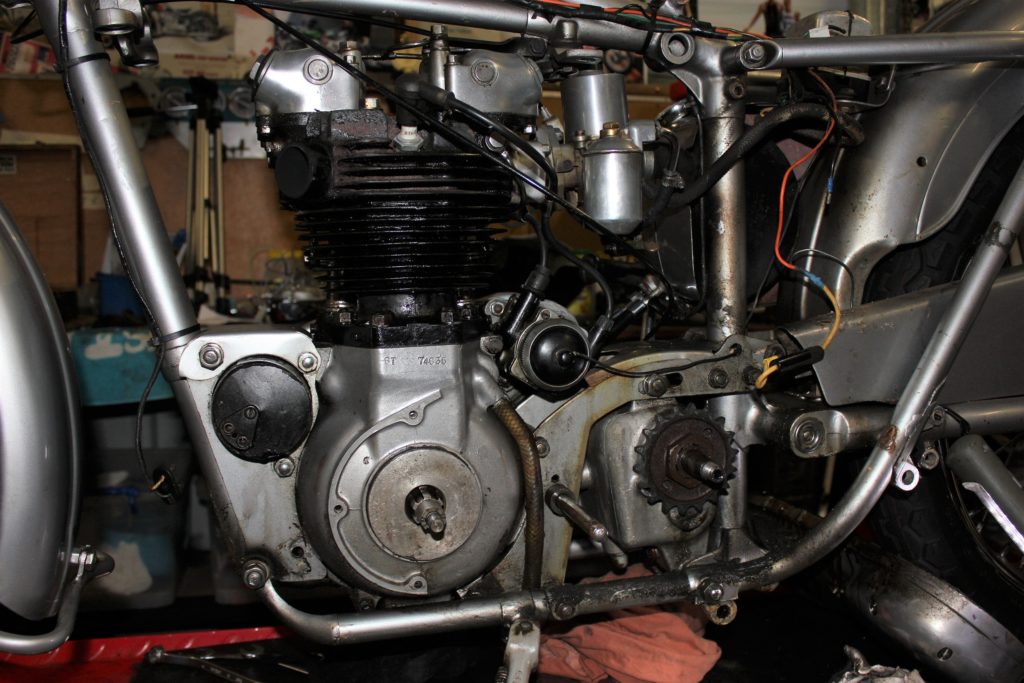

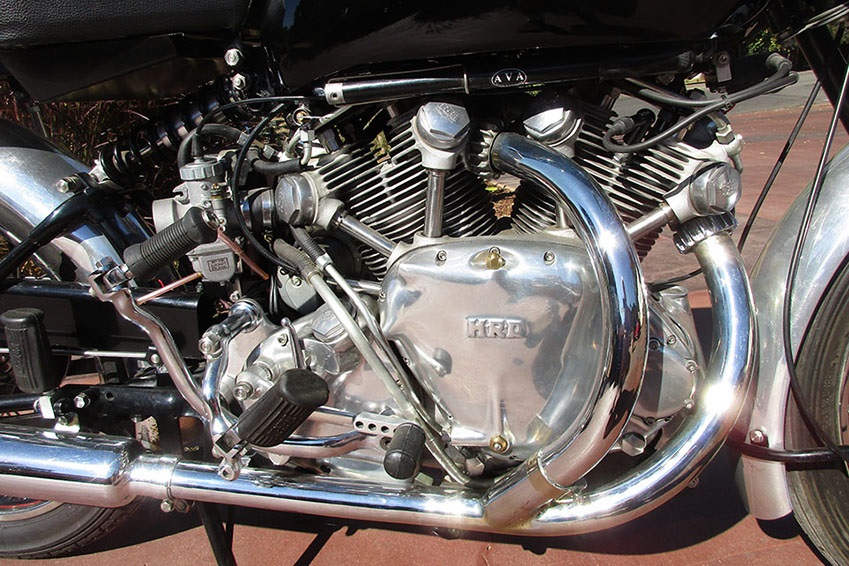

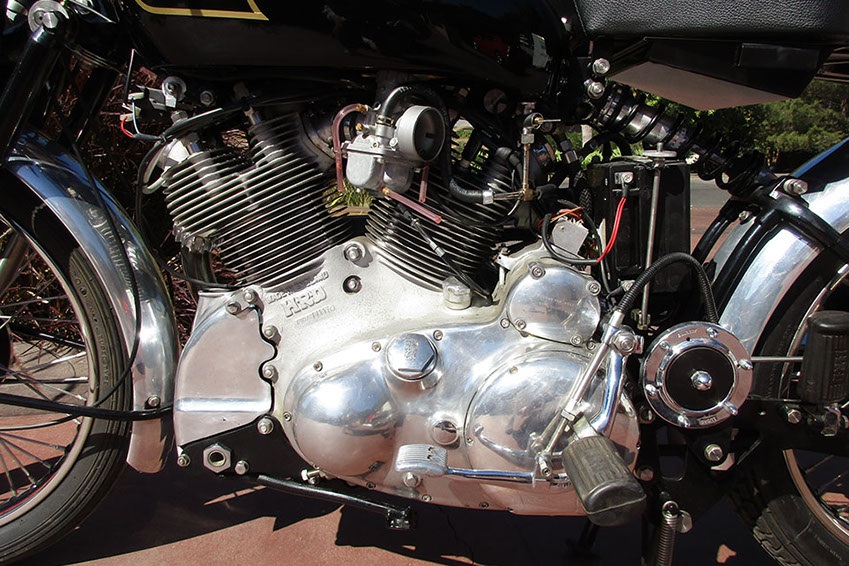

At the heart of the Vincent, indeed the great majority of the bike, is the stonking, huge v-twin engine. One of the most iconic images in in all of motorcycledom.

Throughout the life of the Vincent motorcycle a few names come to the fore, Howard Raymond Davies (HRD), Phillip Vincent, Phillip Irving and Terry Prince. There’s a great many others but those four gentlemen feature prominently in Vincent discourse that I’ve been drawn to over a lifetime of consuming information on the marque. With Terry Prince being the only who is still alive, and therefore still active in Vincent engineering, he is keeper of the Vincent flame. Terry is known around the world as one who will manufacture a complete, Vincent engine, and even the whole motorcycle, using modern engineering and materials.

Terry Prince (far left), has a life-long association with the Vincent marque and is recognized today as one of the most knowledgeable people in the world as an expert of these unique machines. Terry is photographed here at Bonneville Speedway where his 60 year-old motorcycle set a world land speed record in 2010 – with Terry at the controls! Photograph courtesy Terry Prince.

When a 1948 Vincent Rapide popped up on the market laying claim to having been restored by Terry Prince consisting 85% of new parts it well and truly pinged my motorcycle radar. Here was a Vincent that promised a balance between original, precious metal and a road-going, reliable link to the iconic motorcycle. The advertising blurb read, amongst other things, “Prince’s hand is evident all around the bike, starting with the front brake hubs, which contain four-leading-shoe internals. Suspension has been upgraded with modern dampers front and rear. An accessory tread-Down centre-stand eases parking chores. The Shadow 5in. ‘clock’ perched atop the forks is a nice touch. Of course the engine – just overhauled by Prince and breathing though modern carbs.”

The Black Shadow, 150 miles per hour, speedo is a nice touch to my Rapide. Indeed, many Rapides are upgraded with the massive 5 inch instrument.

The 5 inch clock is a massive speedo that has been lifted from Vincent’s own hot-rod, the Black Shadow. Rumour has it people have been booked for speeding by police who have been able the read the speedo from a position slightly astern of an errant Vincent rider. There were some other Shadow touches that added to the desirability of the machine, although, it should be said, a Vincent Rapide in stock trim is a highly desirable machine on its own.

I resolved to call Terry Prince.

Having made the decision to call Terry, I found I was a bit nervous. What if I wasn’t deemed competent to own a Vincent? I had let opportunities of ownership slip through my fingers in the past, maybe the motorcycle gods had already decided I wasn’t eligible to join the ranks of Vincent owners. Or, perhaps it could be fatalism with all the other machines being pushed aside until this one came along. With all the nervousness of a job interview I made the call.

Dave “Bones” McLauchlan racing Terry Prince’s Vincent solo bike. The engine in this machine is producing more than three times the power of its original output! Photograph courtesy Terry Prince.

Within moments of calling Terry Prince I was relaxed and we were chatting like old friends. The more we talked the more I wanted that motorcycle. I learned the bike had been reassembled by Terry from a basket case presented to him along with a Vincent Black Shadow. At the time of building the machine it was Terry’s intention keep it as his personal everyday rider, which reinforced the notion of no expense spared when it came to building the machine with upgraded brakes, suspension, modern carbs and electronic ignition.

At the time of calling Terry two other people had expressed an interest in the bike and one was particularly serious, so serious in fact the bike had been shipped from the US to Melbourne as the prospective purchaser lived in Victoria. How the bike came to be in the US is a long story, but, at the time of my call, it was still sitting in California.

Before the bike was due to leave the US a Black Shadow came up for auction in Australia and purchaser number one was keen to bid on it and Terry was prepared to hold the Rapide pending the outcome of the auction. Evidently he won the auction, with a bid of $AUD160,000, as two days later when I phoned Terry he hadn’t heard from either gentleman and the way was cleared for me to send my deposit to secure the motorcycle. I hurriedly sent off a great chunk of the funds I had set aside for my daughter’s forthcoming wedding (sorry Love).

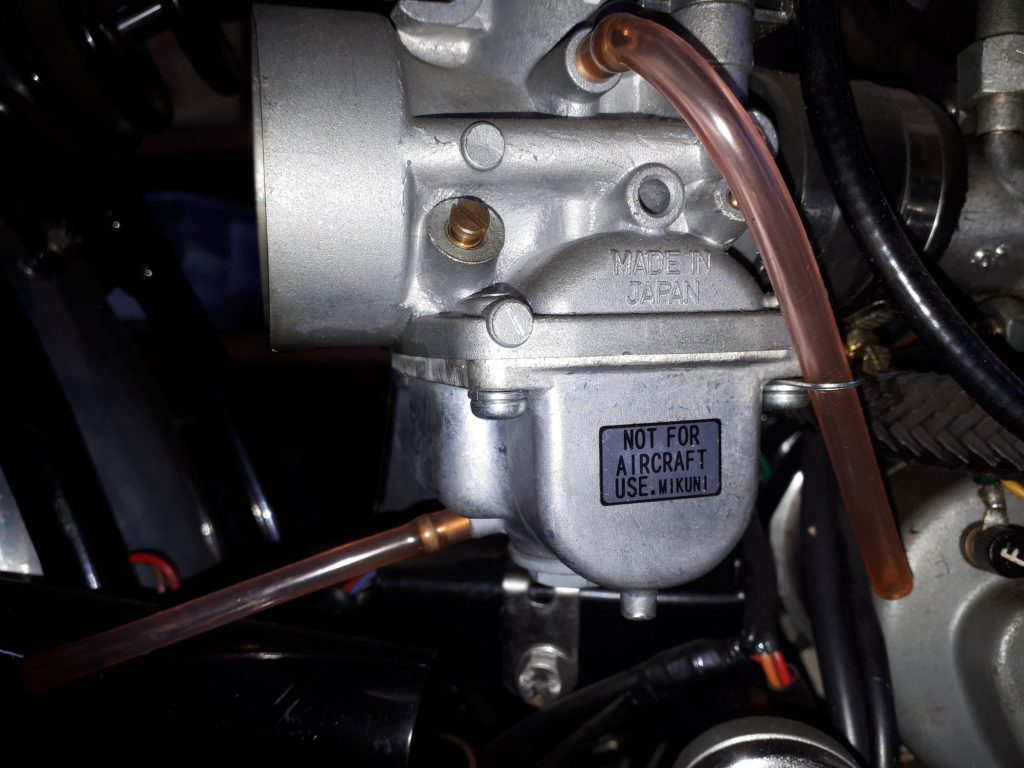

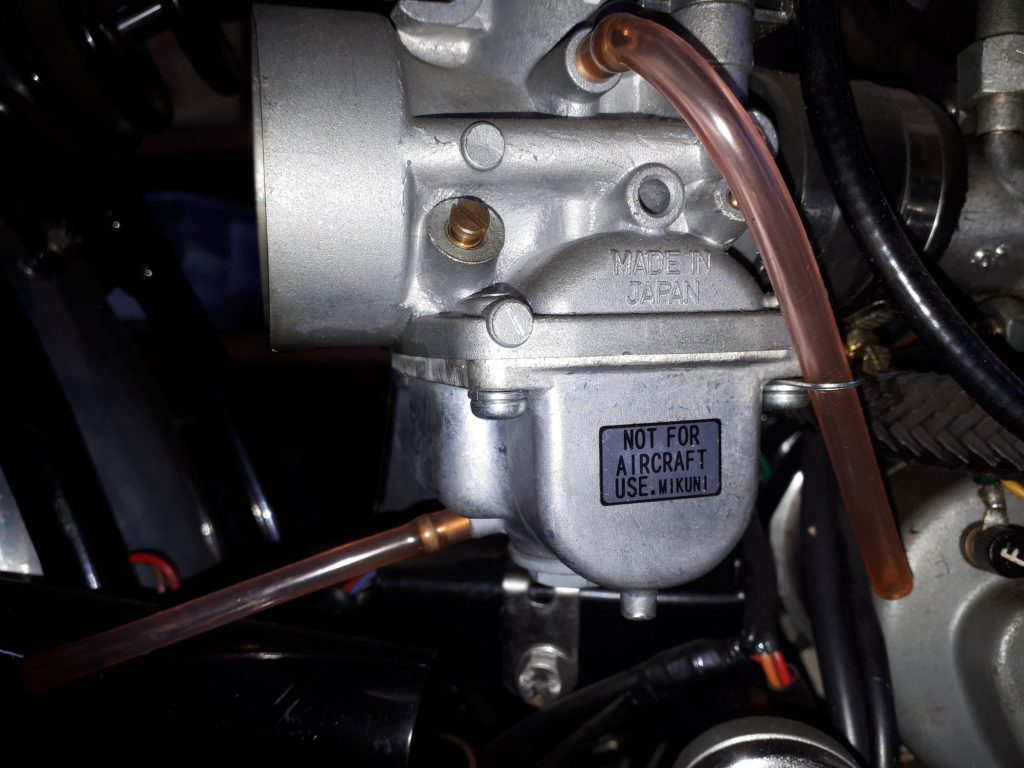

“Not for aircraft use,” probably not for Vincent use either in my book. Mikuni carburettors work well on Vincents, and in my Triton, but having desired a Vincent for over 40 years and pouring over countless machines, photographs and references of these fascinating motorcycles, everytime I look at my Vincent, my eye falls to the Japanese carbs. They will probably be replaced with original Amal items in the very near future.

Sometime later the Vincent was loaded on a ship destined for Melbourne. I waited a few short weeks and as soon as the boat berthed in Melbourne I booked my flights, first to Melbourne to check out the bike and secondly to Sydney to meet the man himself and hand a cheque over.

10 weeks after striking our deal I was standing in front of my Vincent (I still get a pang of excitement when I say ‘my Vincent). She’s a beauty. After two years in the US she’d lost a bit of lustre but I know within a few hours of the bike arriving in my shed she will be looking as good as new. I spent a couple of hours running my eyes and hands over the bike and heard her running. Satisfied with my purchase I set off for Sydney.

A 40-year dream of owning a Vincent motorcycle is a reality.

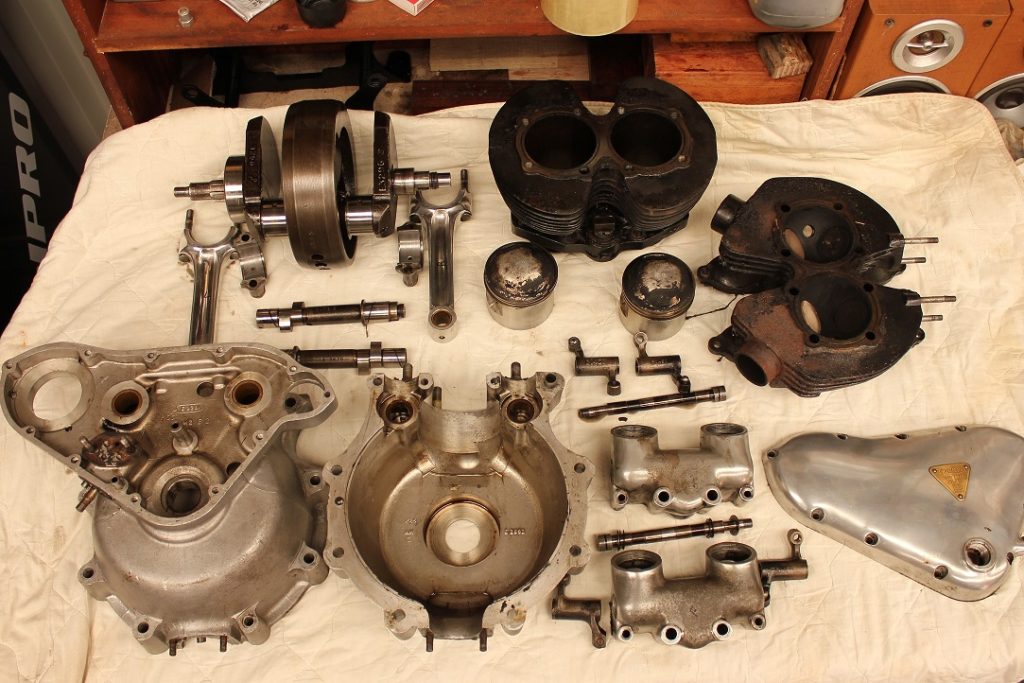

Arriving at Terry’s forest hideaway I’m met first by Ursala and then Terry comes out to greet me. Again, I’m immediately at ease with this couple who have invited me into their house for the night. After coffee and a chat I was treated to a visit to the workshop. There was four Vincent motorcycles and an at least one complete engine in the workshop. I was particularly intrigued by the engine because it is a new one, made from all new parts. Sadly, the parts don’t simply just bolt together and, out of frustration, it has been sent to Terry to rectify and make usable, causing him a host of frustrations. Had he been on the job from the get-go it would be fine but now Terry is having to go back to bring someone else’s work up to spec. It’s a difficult and costly task which, at the end of the day, will result in someone having spent a lot of money for a replica Vincent engine.

Standing in the workshop, I’m juxtaposed between the old and the new, where items from this century and last are found in the same engine. Terry’s original engine, one he’s owned for close to 65 years, sits in a modern chassis and is reportedly pumping out over three times its original 45 horsepower. That same engine has also seen regular service in Terry’s Land Speed Sidecar – which still holds world records at Bonneville Speedway. This creation is not unlike Bert Munro’s famous Indian, except Terry started with better stock in the Vincent than a clunky, old vintage Indian.

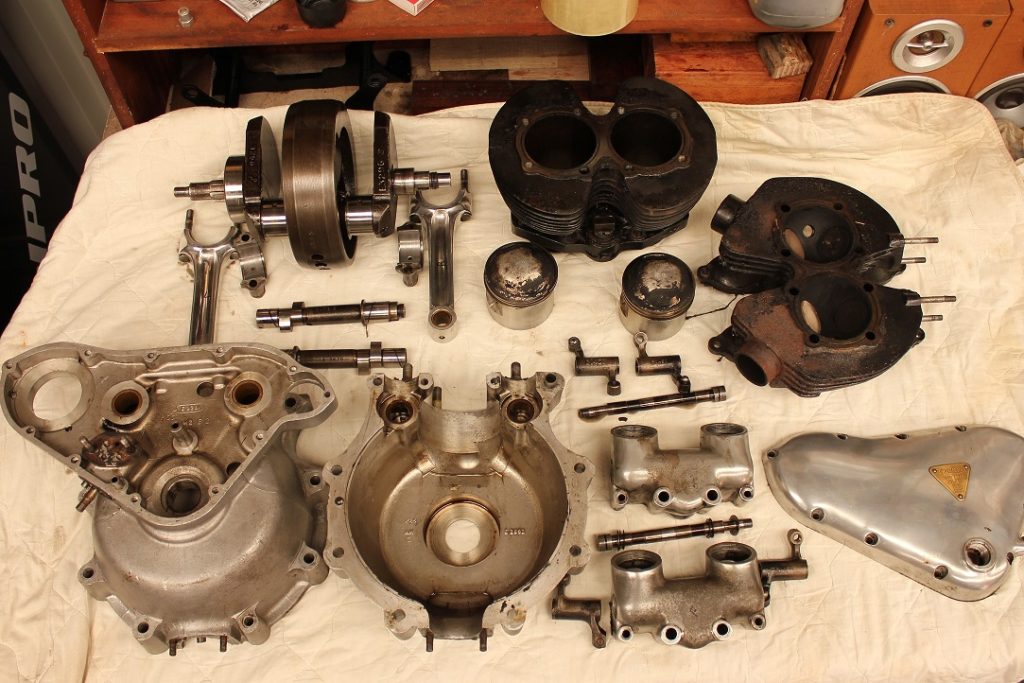

The stock of new parts, heads, barrels, pistons and just about everything that has a thread is tantalising. One of my close calls to Vincent ownership includes me recently bidding on a pair of Vincent crankcases. Two lumps of alloy that were sold for close to $AUD5,000. At the close of the auction I was slightly relieved not to have been the winning bidder, a relief that was even more palpable when I saw the look on Terry’s face as I recounted the story. Suffice to say I would have been up for a lot of money to bring those crankcases up to anything resembling a functional engine.

Anyway, I needn’t worry about that now as I have the genuine article complemented by some modern parts that maintain the authenticity of a 1948 motorcycle in a package that will outlive me, even if I ride it every day for the rest of my life – which is exactly what I plan on doing.

by Dan Talbot | Jul 15, 2019 | Projects

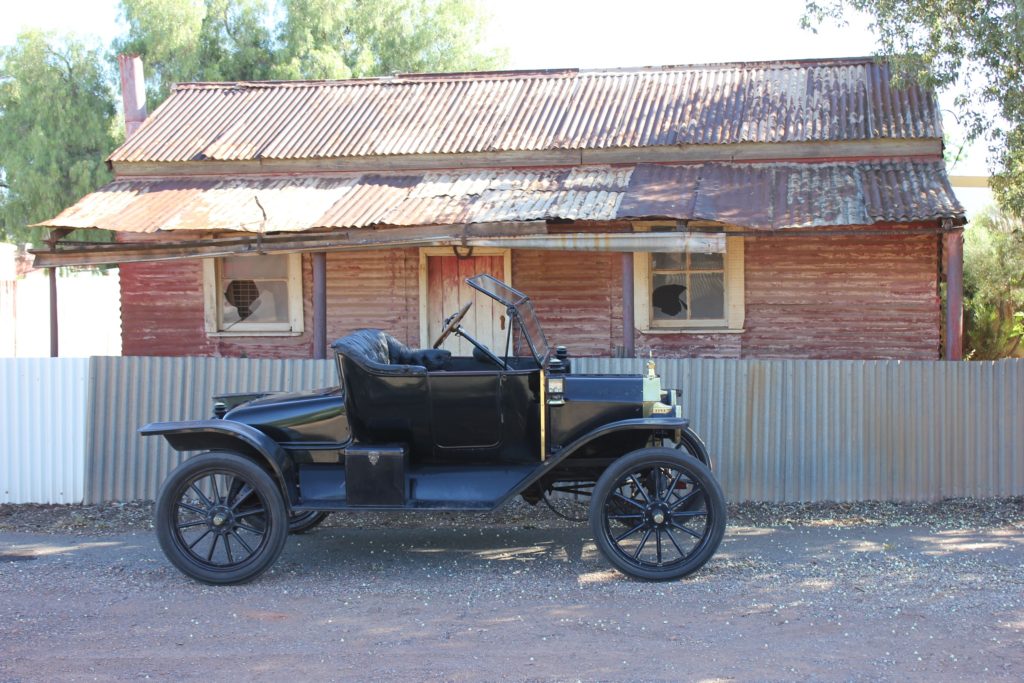

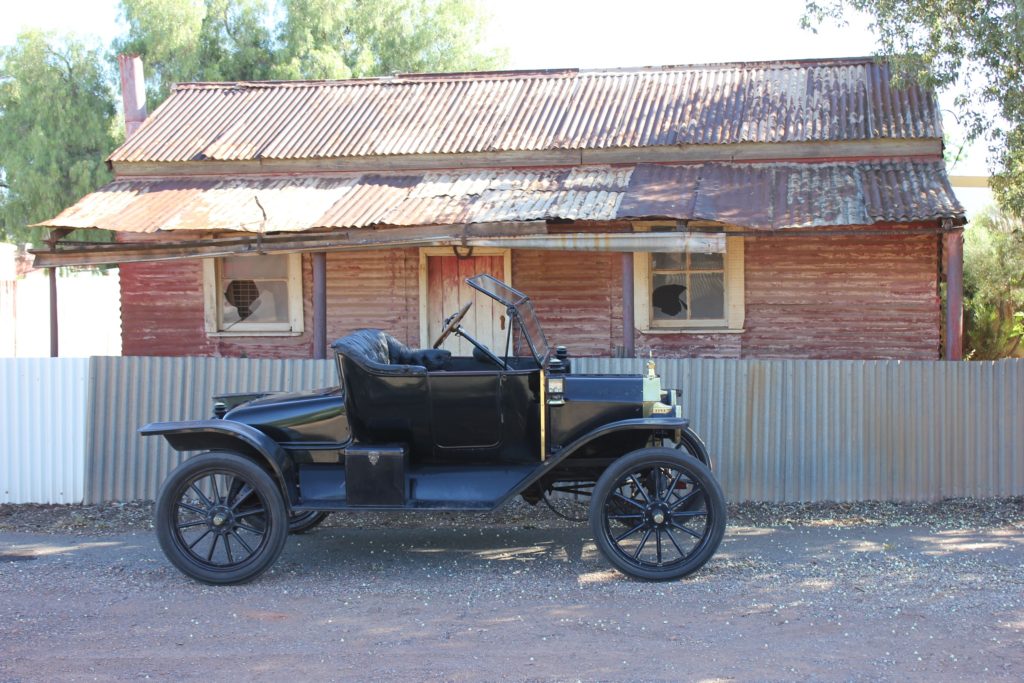

In the few months since we started the Motor Shed site, our Model T has remained quietly undercover, out of sight and out of mind. With the Red Dust Revival looming at Lake Perkolilli in September it’s almost time to pull the cover off and begin to prepare the old girl. It’s also way past time we introduced you to our Tin Lizzie*.

When one thinks of a roadster, thoughts invariably turn to grace and speed, an open-air, two-seater often with some degree of racing pedigree. What most people do not realise is, long before the automobile was invented, the term roadster was originally used to describe a horse that was deemed suitable to ride on a road (yes there were roads before the automobile, you can thank the Romans). It is unclear when the first roadster motor car came into being but, in 1909, just as the automobile industry was gathering momentum, Ford introduced its version of the early sports convertible. Barely five years later, our Lizzie rolled off the production line at Highland Park, Detroit, Michigan.

Long before the ute, the basic Ford Model T chassis was profoundly utilitarian, finding application in anything from tourers, trucks, coupes, fire-trucks, ambulances and even busses. The Model T roadster is a stripped-back, bare-bones sports car, although ‘sports’ is a bit of a stretch as the performance didn’t quite pin the ears back.

The 4 cylinder, 22 h/p, 2.9 litre, 4-cycle engine used across the Model T range had a maximum speed of 80 kp/h (@1900 rpm). The engine was started by hand-cranking, fired by trembler coil ignition, cooled by thermosiphon and lubricated by ‘splash and gravity.’ Final drive is via a 2-speed, planetary transmission actuated by bands rather than a conventional clutch. At the rear, bevel cut gears run in an enclosed differential at a ratio of 3.64/1. Primitive by modern-day standards, the set-up has proven to be remarkably reliable over the years. Indeed, if we had more time, it would be feasible to drive the old car the 800 kilometres to Kalgoorlie for the Red Dust event but touring is not our Lizzie’s forte.

The 4 cylinder, 22 h/p, 2.9 litre, 4-cycle engine is started by hand-cranking, fired by trembler coil ignition, cooled by thermosiphon and lubricated by ‘splash and gravity.’

Our Roadster comfortably seats two adults, three at a squeeze. It only has one door which opens on the passenger’s side to allow occupants to step from the car onto a sidewalk rather than into the street (thus avoiding stepping into the waist product of that other roadster – the horse). It had a removable soft-top, minimal luggage compartment and a top speed of 45 to 50 miles per hour. As a vehicle for the masses, the roadster was, at best, impractical, but that may be where the success of the roadster lies. Roadsters make a statement, they say, “This is a driver’s car, its sole intention is to deliver the thrill of driving for one or two people, with little regard for protection from the elements.”

T FOR 2 – not always! Photograph by Donnalea Wilyman

Our Roadster was imported by my father shortly before he fell ill and became unable to drive. Dad’s illness grew worse and, about four months after he licensed the Model T, Dad passed away. He got to drive the car for one weekend before it was parked whilst Dad went in for an operation from which he never properly recovered. The car sat in the shed for about 18 months before my step-mother elected to sell it. Whenever I walked into the shed the T would be sitting there. From what I could tell, it was a sturdy example of an original Model T Ford. In the back of my mind I started to picture myself behind the wheel, so too had my wife. She was already one step ahead of me and decreed the car would not be leaving the family. It wasn’t as if we needed another project, I had the Mustang sucking time and money and here we were trotting off to the bank asking for a decent-sized wedge to purchase a car I never, in my wildest dreams, anticipated owning. Of course that all changed when I began to drive the car and immersed myself in the veteran car culture.

2014 was our Tin Lizzie’s 100 year birthday. Here she is photographed in Kalgoorlie at the National Veteran Car Rally.

Our roadster is a joy to drive. It’s hard to start and complicated to get moving but once we’re chugging along things are really quite pleasant. In fact, once you’re in second, aka top gear, all there is to do is sit there and steer. In the first ever form of cruise-control, acceleration is controlled by a hand throttle lever which ratchets along a quadrant fixed to the steering column. One is required to advance and retard ignition timing by hand and fuel mixture can be adjusted from the driver’s seat but apart from that there is very little to do as the veteran engine chugs along at about 1500 rpm.

Photograph by Graham Hay.

Our car has spent the majority of its 105 years in the New England region of the USA. Even by the 1950s the vehicle was considered a vintage car and it was driven to numerous veteran and vintage car rallies across the United States. The car was maintained by well-known Massachusetts Ford mechanic Ed Stein and nurtured by the owner Mr Carl Englund Snr of Ossipee, New Hampshire. Upon Mr Englund’s passing in 1997, ownership was transferred to his son, Carl Englund Jnr, and the car was taken to New York where it remained for another 10 years before being purchased by a collector in Texas. In an email sent to me shortly after we purchased the car, Carl explained that he had to let the car go after it backfired whilst he was trying to start it. The crank swung around, hitting Carls hand and breaking several bones therein.

The roadster was imported into Australia by Dad in 2012. It was licensed soon after Dad took delivery and the car remains largely unchanged from the days when Mr Englund charged through the New England countryside in his driver’s car. Indeed, it remains largely unchanged from the day it rolled off the production line at Highland Park, Detroit, Michigan on 18 March 1914 which, incidentally, was a Wednesday.

Our Tin Lizzie sits out the front of the Broad Arrow Tavern during the 1914 National Veteran Car Rally in Kalgoorlie. Photographed by Donnalea Wilyman.

*The origins of name Tin Lizzie; In 1922 a championship race was held in Pikes Peak, Colorado. Entered as one of the contestants was Noel Bullock and his Model T, named “Old Liz.” Since Old Liz looked the worse for wear, as it was unpainted and lacked a hood, many spectators compared Old Liz to a tin can. By the start of the race, the car had the new nickname of “Tin Lizzie.” But to everyone’s surprise, Tin Lizzie won the race. Having beaten even the most expensive other cars available at the time, Tin Lizzie proved both the durability and speed of the Model T. Tin Lizzie’s surprise win was reported in newspapers across the country, leading to the use of the nickname “Tin Lizzie” for all Model T cars. The car also had a couple of other nicknames—”Leaping Lena” and “flivver”—but it was the Tin Lizzie moniker that stuck (ref https://www.thoughtco.com/nickname-tin-lizzie-3976121).

by Dan Talbot | Jul 7, 2019 | Collection, Projects

“Here was an utterly beautiful engine, lithe, angular and a metallic onomatopoeia for power (Frank Melling, Motorcycle USA).”

Written 82 years ago, when onomatopoeia was a still a thing, Mr Frank Melling had just sampled Triumph’s 500 cc Speed Twin and was clearly impressed with his test ride. Frank was actually saying the Triumph engine sounds as good as it looks and who could argue? The Speed Twin was by any measure a huge success and introduced an engine to the world that would take the company into the eighties.

Such is the success of the modern Triumphs, one could be forgiven for thinking the Thunderbird is a relatively recent addition to the line-up. In truth, the Thunderbird was released in 1949 and gained instant notoriety as a genuine 90 mph superbike and the machine of choice for bad boys around the world, due in no small part to the character portrayed by Marlon Brando in the movie The Wild One. We’ve previously discussed the history of the Thunderbird on the Motor Shed and it can be revisited here. This piece is about the restoration work our Thunderbird has enjoyed since coming into our possession over 20 years ago.

During most of that 20 years I had been looking at my 1956 Triumph Thunderbird thinking, “I’m not happy with the grey frame.” The bike looked pristine when we acquired it but after many years of use and abuse the lustre began to wear off and she became in need of a spruce up, giving me the ideal excuse to pull the bike down and do some colour changing, amongst other things, more important things as it would turn out.

- The all-silver livery of our ’56 Triumph Thunderbird never really grabbed me. What I really wanted was a Blackbird, or so I thought.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, the Thunderbird engine actually needed to be completely pulled apart. With the greatest respect to the person who rebuilt the bike before we acquired it, there’s a critical piece deep within the engine that has a finite operational life and it needs to be replaced with some regularity but is often over-looked. The plan was to pull the engine out, paint, plate and polish every surface and return the Thunderbird to the road as a new machine.

I had a particular fondness for the rare, all black Thunderbird which was sent to America following the popularity generated by Brando’s gleaming black 1950 machine – in a black and white movie of all things! Long before Honda came out with their four cylinder, plastic-enclosed behemoth, the all black 650cc Thunderbird was dubbed the ‘Blackbird.’ And it’s a stunning machine. Rich, black paint contrasts well with polished alloy and, as is the case with classic machines, highlights the era perfectly. Yep, my ’56 was going black.

- Stunning in black and polished alloy this limited release Thunderbird was dubbed the Blackbird. Photograph provided by Thomas Duffy, the owner of this beautiful machine.

In the weeks and months leading up to me beginning the restoration, trawling through the internet of things I stumbled upon a rare colour combination of silver on black. The bike had been restored by Choppahead Kustom Cycles in Massachusetts and it is the perfect embodiment of the classic Triumph that has been with us since Edward Turner unleashed his famous Speed Twin on a world seeking beauty and performance in a motorcycle. I could no longer look at my all-over silver Triumph in the same way and even the hitherto lusted-over Blackbird became merely a crow. I had moved through the various mental stages of change (you know; procrastination, contemplation) and now it was time for action.

- This ’56 Thunderbird was restored by Choppahead Kustom Cycles of Freetown, Massachusetts. Once I laid my eyes on this bike thoughts of a Blackbird were lost to the ether of my mind. Special thanks to Choppahead for allowing me to use this photograph.

Twenty-something years of use had left its mark in the form of paint chips, faded chrome and rust starting to show through here and there. I was further able to justify the pull-down by claiming the oil leaks needed to be fixed (I’m serious), the magneto needed attention and the cleanliness, or otherwise, of the infamous sludge-trap, was an unknown. Now, I’m the first to agree the term ‘sludge-trap’ has a fictional tone but it is a real thing and ignoring it can destroy a classic Triumph engine, it is the critical piece I mentioned above. In the days before oil filters, some manufactures, in the interest of engine longevity, put a screen filter inside the crankshaft oil circuit. So, let’s have a little think about that – the oil filter is inside the crankshaft. Anyone with a modicum of knowledge around the construction of the internal combustion engine will recognise the inherent problem around this design.

When we first purchased the Thunderbird it looked brand new. Attention to detail was amazing and it ran really well but there was a couple of tell-tale signs of trouble brewing deep inside. Clearly the magneto hadn’t been touched. Once the bike heated up it was extremely difficult to start which is a sign the maggy is on its way out. In a world governed by constants, temperature coefficient of resistance left me having to give the warmed-up 650 an extra, extra hard kick to overcome the resistance of the hot maggy coils in the hope I could generate a spark strong enough to start the engine. Once started, the ancient twin would squirt oil everywhere, including all over my jeans and boots. Oil would shoot out of places hitherto unknown to contain oil or require lubrication. Seriously, oil would somehow hit the bottom of the fuel tank then run of the seams making it look like the tank had its own secret oil reservoir. A degrease and polish would have the bike looking a million bucks but that would only last as long as a decent ride.

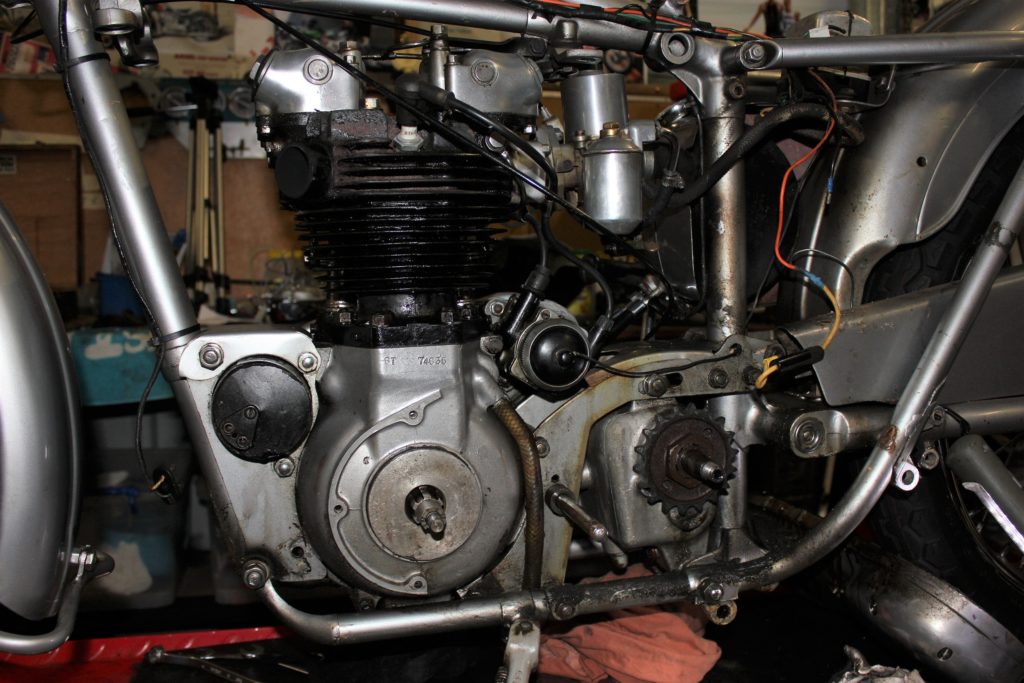

So there you have it, sludge-trap, magneto, oil leaks and beautification were my motivation. The Thunderbird was pushed onto the hoist, anaesthetic was administered and she went under for some major surgery. It’s not as if I had nothing to do. My Mustang rebuild was languishing away quietly in the corner of the shed, my Triton, like an insecure toddler, was in constant need of attention but, by crikey, that Thunderbird was coming apart.

The bike came apart reasonably easily. It was grubby behind all the surfaces that I couldn’t reach with my very thorough detailing but built up oil and grease does wonders for preserving the metal on which it cohabitates. When it came time to turn my attention to the engine, that too came apart really well. There are some specialist tools required and I purchased some and borrowed others. Eventually, I had the engine, in fact the whole bike, down to irreducible parts, in other words, every last nut and bolt had been removed.

The venerable Triumph parallel twin has been with us for over 80 years since it was introduced to the world as the 500 cc Speed Twin. In 1949 the engine grew to 650 cc in the Thunderbird. Note the SU carburettor. In the mid-fifties Triumph experimented with these carbs and they proved successful but were possibly too expensive to continue with.

- The 650 cc engine.

I was more than happy to learn the big-end bearings were marked as “std” which indicated the crank had never been ground. Bonus. The bearings were also stamped with 08JU90 so I could safely say the engine had been rebuilt sometime between 1990 and 1993. Recall from part I, we bought this bike after it had been restored, sold to an intermediary, sent to the UK where it sat in a container for two years before being returned to WA.

The pistons were .20 over which indicates in 62 years the bike had only undergone one rebore. I began to think ‘maybe new pistons, rings and bearing would be enough.’ And maybe not. Here I was contemplating ignoring one of the primary reasons I pulled the engine apart, mainly because I was out of my depth. The crank would need to be handed over to the experts to expunge the sludge, of which, there was plenty. Like the tailings from of some black gold mine, the substance had a hint of a sparkle from decades of engine grinds mixing with mud and other impurities. Just as well we looked.

- The sludge removed from deep within the crankshaft of my Thunderbird had a hint of a sparkle from decades of engine grinds mixing with mud and other impurities.

- The engine is out of the bike and about to be pulled apart. Note the ever-present camera which will record the proceedings with about 500 photographs, a practise that has proven invaluable over the years.

- Back in the nineties the Thunderbird was a bit of a farm-hack on our family property.

- 20 years later, same motorcycle, same kids.

by Dan Talbot | Jun 30, 2019 | Projects

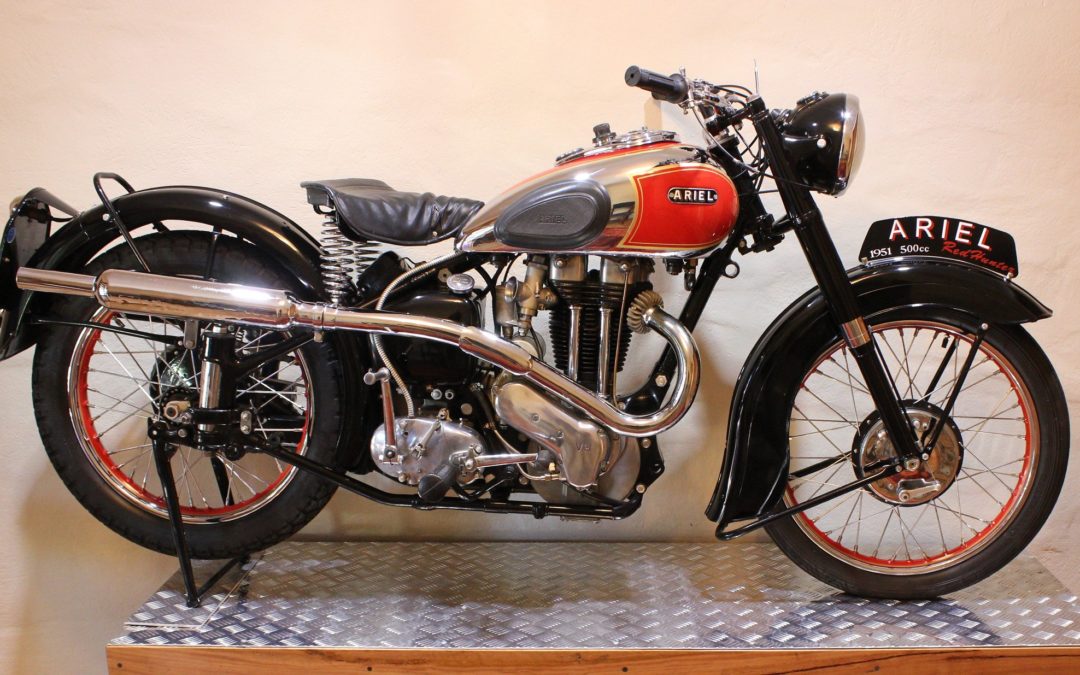

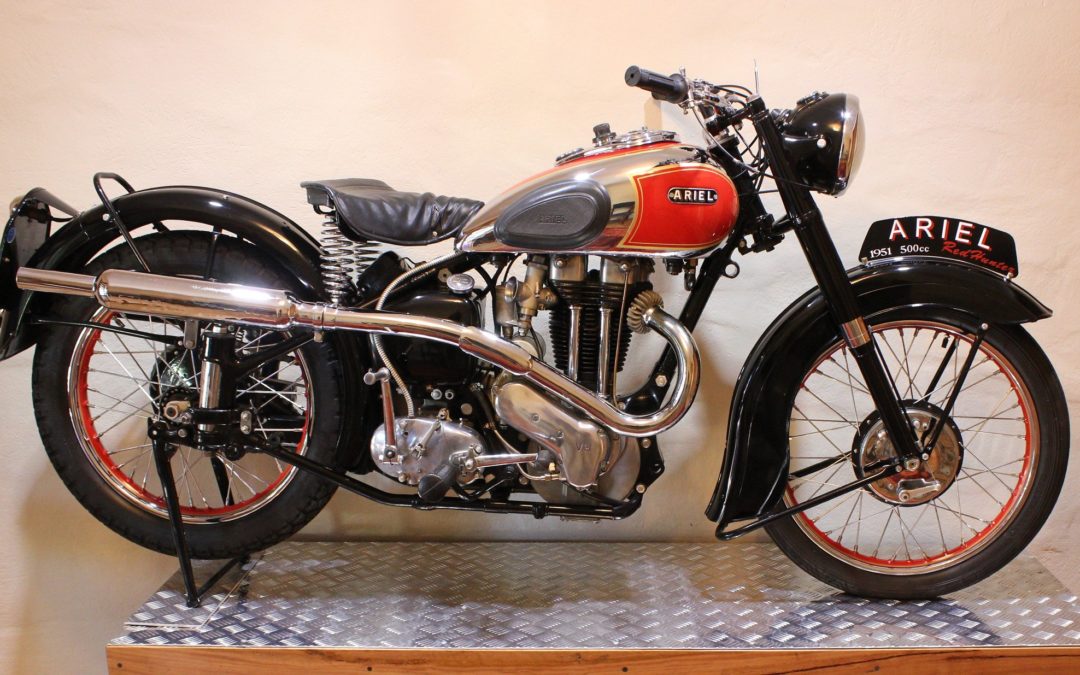

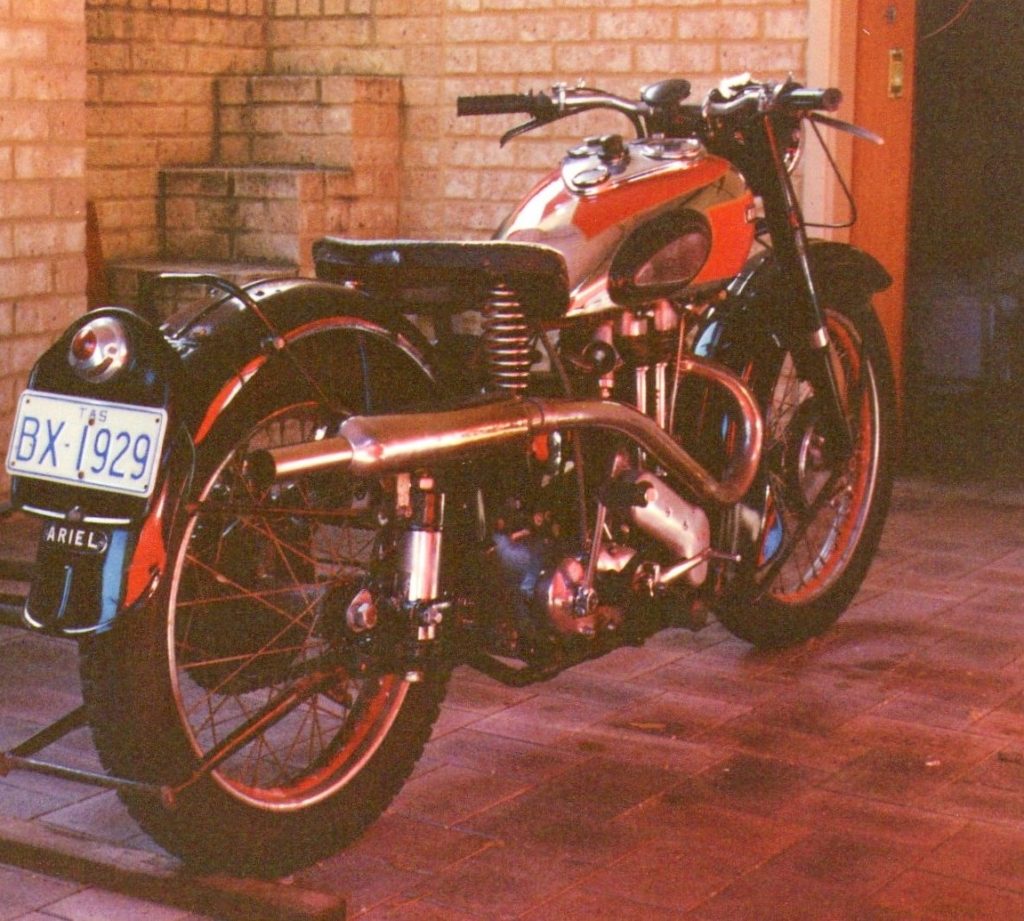

This is the third instalment from “Rebuilding the Ariel,” available on this site in eBook format.

When Dad told me he had purchased an Ariel I was unaware he had owned one as a teenager. To be honest, I wasn’t all that familiar with the brand and had to do some research to learn more about the Red Hunter. There was no google back in those days, I had to learn the old fashioned may, with books and tuition. The tuition came via friends and acquaintances and it was from one of these latter sources I learned Dad used to own a Red Hunter when he first hit the streets – legally that is. I also learned the bike was considered a spirited performer and, by all accounts, a handsome machine. Sadly, Dad’s purchase wasn’t such a great example in terms of presentation but she ran okay and performed admirably for a vintage motorcycle.

The 40 year old machine had at some stage undergone a restoration but it was in need of a lot of work to bring it back to pristine condition. For example, just casting an eye over the bike revealed the ‘Ariel’ tank badges held in place by epoxy-resin glue, the engine wasn’t all that oil-tight, the chrome plating was blemished and rusty, as was much of the tin-wear. Most of that work was going to have to wait a while. My father was never one for aesthetics and he was quite content to leave the bike as is.

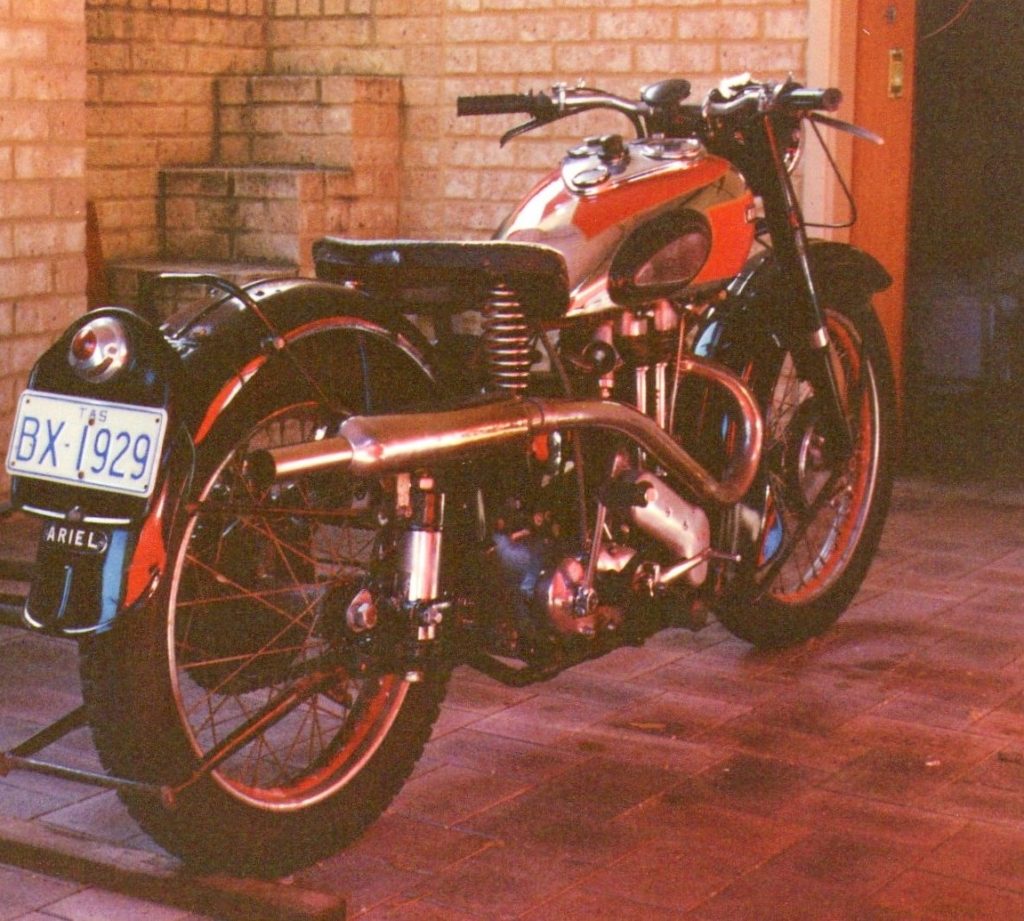

Dad was not that big on riding his vintage machinery so seldom felt the need to licence a bike immediately upon receipt. If a bike was licensed it generally stayed that way. The Ariel arrived bearing a Tasmanian registration plate, which was good enough for Dad, by the time the registration would run out he’d have enough of the bike anyway. Additionally, there are some fairly quiet country roads and lane ways around the farm where aging bikes, and riders, can be taken for a spin.

Having said that, to my knowledge, whilst the Ariel was in Dad’s shed, it was rarely ridden beyond the driveway of the farm, probably because the driveway is over one kilometre long and by the time you got to the end of it on the ancient machine, frazzled nerves meant one was usually ready to turn around and ride back to the shed. I might add the driveway is gravel, usually corrugated, potholed and dusty. As a teenager it caused no end of consternation to finish a polishing job on my latest pride and joy only to have it look like a trail bike by the time I made it to the bitumen.

The Ariel was a bit rough when it arrived from Tasmania but it ran well and came up alright with a bit of wax and elbow grease.

Aside from the trials and tribulations I have already attributed to the Ariel, once I got over the hinginess of the frame and lack of brakes, I actually learned to love riding it, I still do. That big, old, long-stroke 500 cc piston chugging and shaking beneath the fuel tank (itself vibrating about on its mounts), the induction noise pop-pop of exhaust all add up to a wonderful experience. Once underway, with the timing set to a suitably advanced position, the bike was a joy. I recall back in the early days of riding the Ariel when I finally realised why the big British singles were referred to as “one-lung” bikes. The engine acted as a bellows that sucked air in and coughed it out. Roaring down the road, the big single almost took on the biological aspect of the lungs from some large beast.

At this stage it is evident that I did get beyond the bottom of our driveway. I can’t recall how many rides I took the bike on whilst it was still bearing the old Tasmanian registration but eventually that ran out and Dad chose not to take out Western Australia registration. By that time, having been a bit of a ‘farm-hack,’ the bike would have needed a fair amount of work before it would pass examination so that was going to have to wait. The Ariel mainly sat in the shed as Dad focused his attention towards some of his other many and varied pursuits.

For a long time the Ariel seldom turned a wheel and only received attention during one of my infrequent visits to the farm. As it transpired, the responsibility to get the machine up to roadworthy standard would be vested in me.

Our weekends.

Looking back, it actually took a great deal of work to bring the machine up to club licence specifications. Back in those days, raising children and a hefty mortgage meant finances were tight. In motorcycling it is pointless, and in some cases dangerous, to cut corners. This would see me scrimping and saving money to be tipped into the project. The result was well worth the effort and by the time the machine was roadworthy I knew my way around it very well, but it did take a while to accomplish.

At this point, I should explain the Ariel was restored twice by me and at least once by someone else. My first restoration was purely mechanical, mainly to get the bike roadworthy and ready for concessional licensing, chrome and paint would have to wait until I could afford full rebuild – some 20 years later. The rebuilds had quite different objectives, which will become evident in the chapters which follow (recall this is an excerpt from the book Rebuilding the Ariel).

When the Ariel arrived I was living and working in Esperance on the South-Coast of Western Australia, some 650 kilometres from the farm. Back then, we would get up to the metropolitan two or three times a year, which usually included at least one visit to the farm.

Generally, soon after arriving at the farm, I would wander out to the shed and begin tending to one, or more, of Dad’s bikes. Working alongside Dad in his shed was a good way to converse. Never one to sit and have a chat, Dad was more at home with banter about the machinery that occupied his spare time. Frequently he would demand to know what I was doing about the latest high-profile homicide or whatever crime was being reported in the media, between welding strokes of his latest project.

I usually finished off the maintenance with a good polish followed by a ride.

My favourite bike in Dad’s collection was undoubtedly the Thunderbird. Dad finally managed to secure the 650 Triumph a few years after the Ariel. It was a particularly nice example of a 1956 machine that is, by all accounts, rather rare. The Thunderbird is fitted with an English SU carburettor and finished in all-over silver, including the frame, which I was told indicates it was an export destined for Australia, although I have since discovered that to be false.

Ariel bobber photographed at Peel, Isle of Man, during TT week in 2018. Note the front disc brake – we dream of such things for the Motor Shed Ariel.

Despite what was apparently a fine restoration, the Thunderbird regularly needed some tweaking to keep it in order, not the least of which was the odd dribble of oil. Anyone who has ever owned an old British bike, and a good many folk who haven’t, will testify to their capacity to spill their guts from orifices designed to contain lubricant rather than give it liberty. The Ariel was particularly bad for this, therefore maintenance always started with a degrease to get rid of all the oil and built up gravel dust. After I got the Ariel cleaned up I would turn my attention to the Thunderbird.

Artist and dedicated Ariel enthusiast John Hancox leathers display the Ariel logo and hang proudly in his gallery on The Promenade in Douglas, Isle of Man.

The Thunderbird had been lovingly restored by a member of the Vintage Motorcycle Club in Perth. At the time the bike was restored I was in fact a member of that club but there was over 450 members so I was unable to place him. Sadly, the gentleman who restored the bike never got to fully enjoy it as he passed away soon after completing the restoration, receiving “the big chequered flag in the sky,” as the club used to so eloquently put it whenever they lost a member.

The bike was subsequently acquired by an ex-patriot Englishman who very soon thereafter decided he would migrate back to the Old Country. He loaded all his goods and chattels into a container and shipped it all back to the UK. He then gathered up his family and, similarly, shipped them all off ‘home.’ Evidently things didn’t go as well as expected. Upon arriving in England, the gentleman decided things weren’t that bad in Australia after-all and resolved to return. They actually left the UK before the container arrived, and returned to Perth. It took another two years before the container was turned around and arrived back in Western Australia, whereupon the Thunderbird was removed and promptly sold – to Dad.

If this excerpt has wet your appetite, Rebuilding the Ariel can now be purchased online in eBook format right here!

by Dan Talbot | Jun 22, 2019 | Collection, Projects

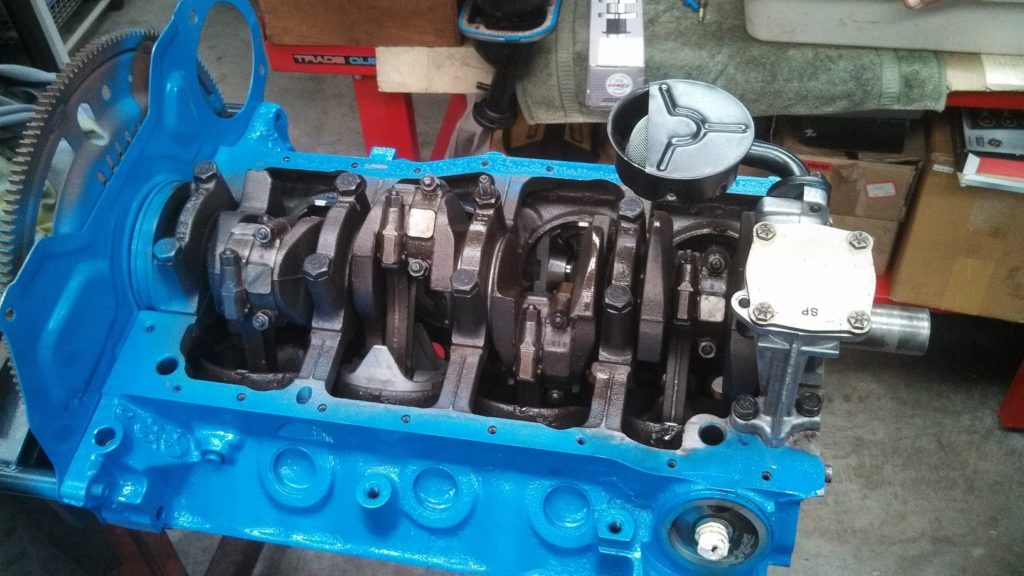

With the Mustang body well on its way to being straight and true, it was time for me to turn my attention to the heart of the beast, a 289 cubic inch Windsor V8. The Windsor story is a fascinating one so grab a cup of tea and we’ll talk a tale of two cities.

In 1904, in what could be the first ever case of badge-engineering, Ford opened a manufacturing plant in Windsor, Canada – across the river from the US Detroit parent company. The idea was to assist the company to gain a foothold into Canada and elsewhere in the British Empire.

Evidently the experiment was successful. The plant later incorporated an engine casting facility and, in 1962, introduced the Windsor V8 engine to an automotive world hungry for power and speed. The modern, new Windsor engine was a marked departure from the previous design and it was an instant hit.

In this ‘everything old is new again’ world, the old Y block V8 is enjoying somewhat of a renaissance amongst hard-core enthusiasts but I’m sure, back in the day, they were quickly shoved aside in favour of the sportier new-comer.

Such was the success of the Windsor V8, production extended long after its replacement when the Cleveland was introduced. In fact, the Windsor was used for another 18 years beyond the short, 13 year span of the Cleveland that ceased production in 1982. The Cleveland engine, as the name suggests, was produced in Cleveland, Ohio. It was intended to be a more robust and versatile engine than its predecessor. The Cleveland lived up to expectations and proved very successful in racing, particularly in Australia where it was a game-changer in the Falcon GT. The Falcon GT was a dream-car to many a teenager growing up in Australia, including me. The advent of the Cleveland, for us kids, signalled the end of the Windsor. Everyone knew, if you wanted to be in the race a Cleveland was the only way to go, notwithstanding both engines came in 351 cubic inch displacement. Like the Y block before them, Windsors were shunted aside and ended up in cars driven by the slightly more wealthy members of my cohort.

But then a strange thing happened, the Windsor refused to leave the stage.

Having pinned their future muscle-car ambitions on the Cleveland, Ford planned to phase out the Windsor in the late seventies, but the perennial heart-beat from across the river had other ideas and Detroit were forced to keep sending it out into the world. It stayed on in 302 cubic inch format up until 1982 when it was re-badged the 5.0 (litre) and remained in production up until 2000 when the last of the fuel injected, roller cam engines were put out to pasture. It was one of those, the last incarnation of the Ford Windsor V8, that I had my eye on for the Mustang.

The tired, duty, oil-leaky 289 Windsor V8 had to go. Note the dedicated gas set-up the previous owner had installed (no doubt at great expense).

My car was from the sixties and it was produced with a Windsor V8 which meant this was the only option. A bonus here is the direct connection to the seventies when those afore-mentioned, financially capable friends of mine were running around garnering my envy in their Windsor-powered cars. Four decades later, I’m set to revisit those days, the days before the fuel injected, refined, perfectly timed and smooth V8s we’ve become accustom to.

Out with the old.

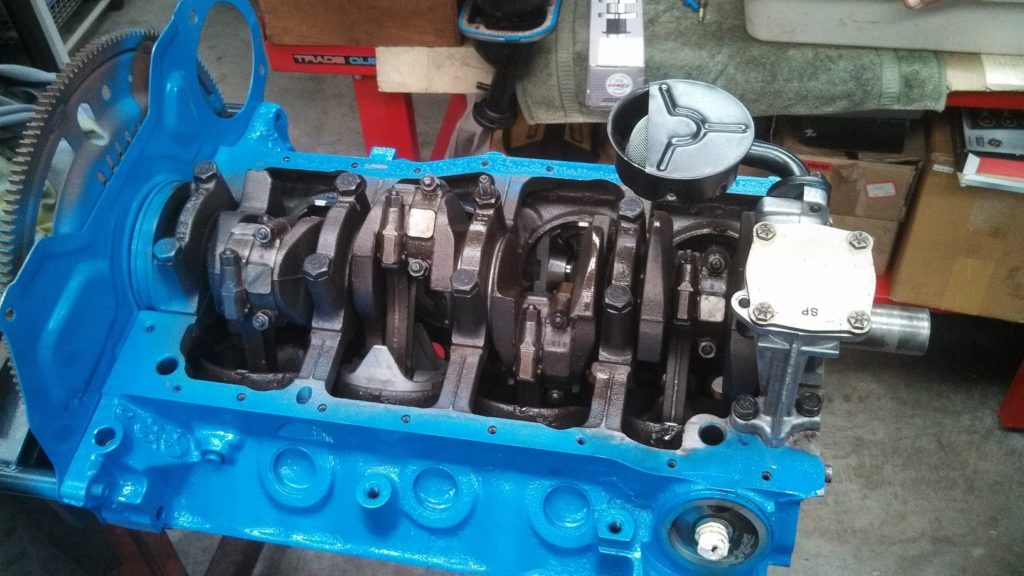

To be fair, there’s no shortage of roller-cam V8 engines looking for cars to inhabit with a lot of people being put off by all the fuel injection hardware that sits atop the engine, they are a natural turn-off. Fuel injecting a Windsor is the automotive equivalent breast augmentation, it looks great but it comes with high maintenance and takes skills far beyond my fumbling fingers to master so losing the fuel injection unit was a must. When I lift the bonnet on my 66 Mustang I want to see a bright blue Ford Windsor V8 at home in there with a 4-barrel Holley breathing through a classic Ford air-filter.

I had read on the internet it was quite a simple task to throw out the fuel injection and return the engine to the less socially acceptable form of fuel delivery from the last century – the carburettor. To achieve this I would mainly need two things, an engine and a carburettor. As it turned out, I would need many things but these two items seemed like a good start (the 289 engine I removed from the car had been gas-powered so there was no carburettor with that).

The 5.0 roller cam Windsor I settled on was a used American imported item falsely described as ‘refurbished.’ I would later learn refurbished is semantics for paint and gaskets, which probably explains why the engine was so cheap, however, there was a bonus: I could take my pick from a nearby pile of carbies. In a nod to the environment, I selected a 480 cfm unit. Sure, it’s got four barrels but it’s in the smaller range of the 4-barrel Holley family and at the end of the day, my car is intended to be a cruiser anyway.

The last hurrah for the Windsor V8 engine. This fuel injected engine was reportedly ‘refurbished.’ In truth, it had a few gaskets replaced. Note all the fuel injection hardware at the top of the engine that had to be removed.

Feeling pretty chuffed with myself, I took the engine and went off to get a Windsor expert to run his eye over it and help return the unit to carburettor fed. Having been with us since 1962, these things are quite rudimentary but, as it turns out, there was a fair bit more required to return a carburettor to the Windsor than I had anticipated. The list included a new inlet manifold, camshaft, distributor, coil, water pump and fuel pump. I wanted someone I could trust to turn me out a good engine at a reasonable price and, to that end, I chose Paul Poller of SpanaWorx Mechanical Services. Paul’s easy-going nature and sensible approach to engine builds was ideally suiting to adapting the 302 for service in my ’66 Mustang.

My bargain engine basically needed a full rebuild. Here, Paul is treating it to a new oil pump – adding to my peace of mind.

There was a prosperous time about 10 years ago when the Australian dollar was on parity with the US greenback and we enjoyed the bountiful US performance market with relatively little trauma to the hip-pocket. Importing used engines from the US was a thing and some of the more creative exporters turned, shall we say Dickensian, in using elaborate terms to sell scrap metal. I accept I jumped into the unknown but I wasn’t expecting someone to have drained the pool.

In she goes. Well almost. The sump got hung up on the cross member and the engine would not seat properly. A simple fix was to swap it with the sump from the 289.

By the time I took delivery of my sparkling blue Windsor V8 it had new rings, bearings, camshaft, alloy heads and host of external parts to add beauty and practicality. The old 289 was no slouch but I’m expecting my new, improved heads and lumpy camshaft will add a few horsepower to the already spritely 302.

Getting close now and relying on Google for some last minute tune-up tips.

My carby was sent off to Xtreme Fuel Systems in NSW where it was transformed to better than new. This is the third carby Xtreme have reconditioned for me and I highly recommend them. I took the carb out of the box and simply bolted it onto the engine. The carb is yet to be dialled in, but the engine burst into life after a few short bursts on the starter motor with a deep rumble that has been absent from my life for too long. It is immensely satisfying to hear that car running again.

Hear it here; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rrb51yf_2W0

The rebuilt Holley carb is a thing of beauty. Xtreme Carburettor Rebuilding in Cambelltown, NSW are highly recommended.

When I lift the bonnet on my 66 Ford Mustang I want to see a clean and tidy Windsor V8 engine breathing through a classic Ford air-cleaner – in this case a Shelby replica.