by Dan Talbot | Feb 7, 2023 | Uncategorized

Rocket Three Restoration: Part IV

Wow, how time flies. The last time I wrote an update on the Rocket 3 project was almost 12 months ago. In my defense, I have been busy with another big writing project which is done so now it’s back to the Shed.

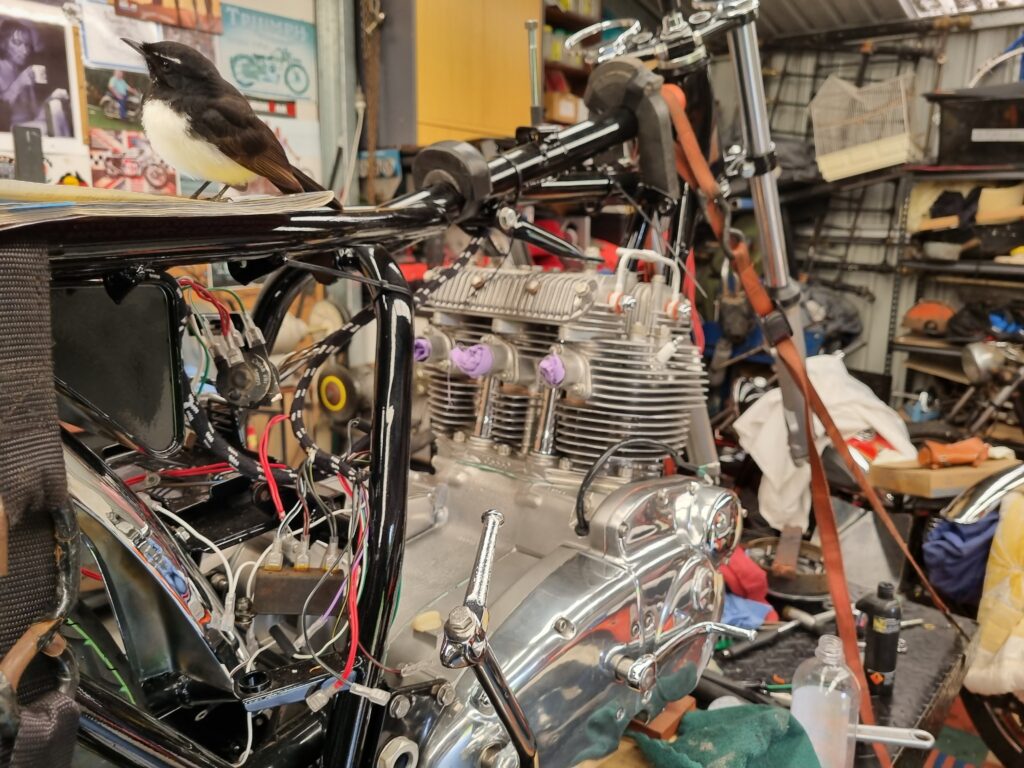

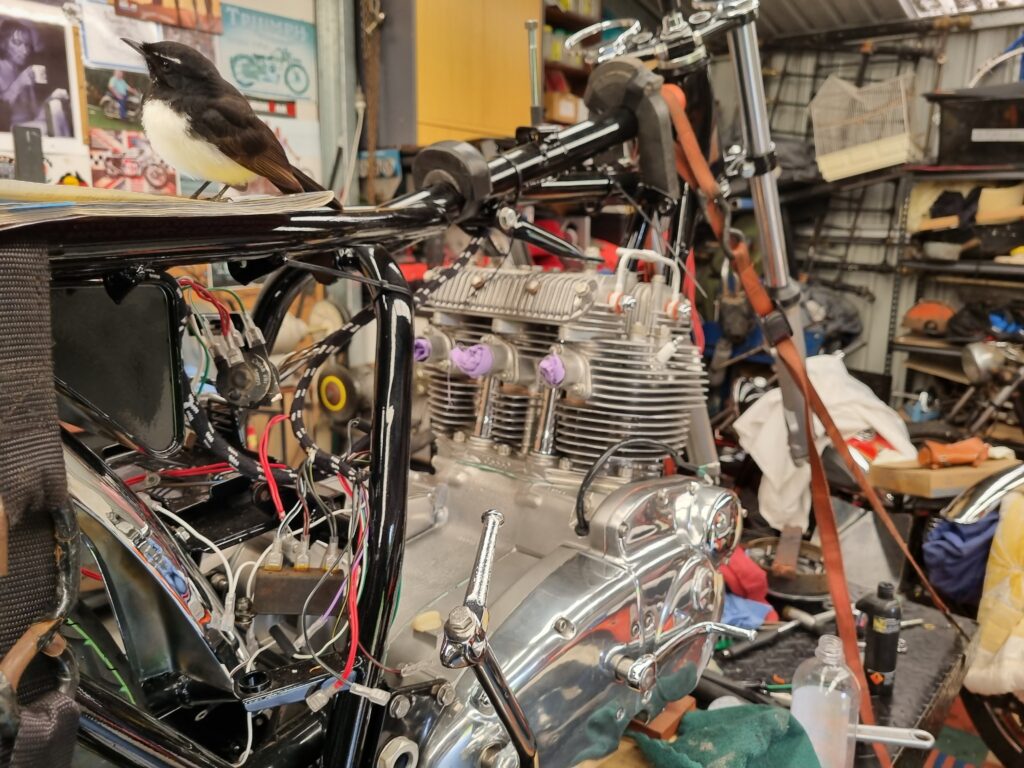

Since I last wrote about the Rocket there has been quite a bit of progress, most notably the engine is finished and back in the frame. The engine, if I may say so, looks absolutely splendid but I can’t take the credit for it’s rebuild. Some months ago, I boxed up all the parts and delivered them to British Imports in the Perth suburb of Malaga. I have no doubt that I would have been fine assembling the engine but there are so many tales of these old triples flying to pieces when not done right. Added to this, recall last time we discussed the Rocket I expressed an idea I may perhaps keep the bike instead of selling it. I tend to be a little harsh on machinery so I didn’t want to leave anything to chance and I would hate to have to remove it again.

One thing about these engines is their incredible weight. I believe it is somewhere around 125kg. This means, if you don’t want to risk scratching the frame or breaking fins of the engine, at least three people are needed to get the engine back into the frame. It’s a tricky job but we got there. This was also the first time the engine had been introduced to the frame so it was somewhat of a blind-date. The big test in how this two were going to get on was the engine mounting bolts. I’m happy to report, with some gentle persuasion the mounting bolts were settled into place and the engine and frame are living happily together.

The 125 kg engine is, at last, nestled in the frame.

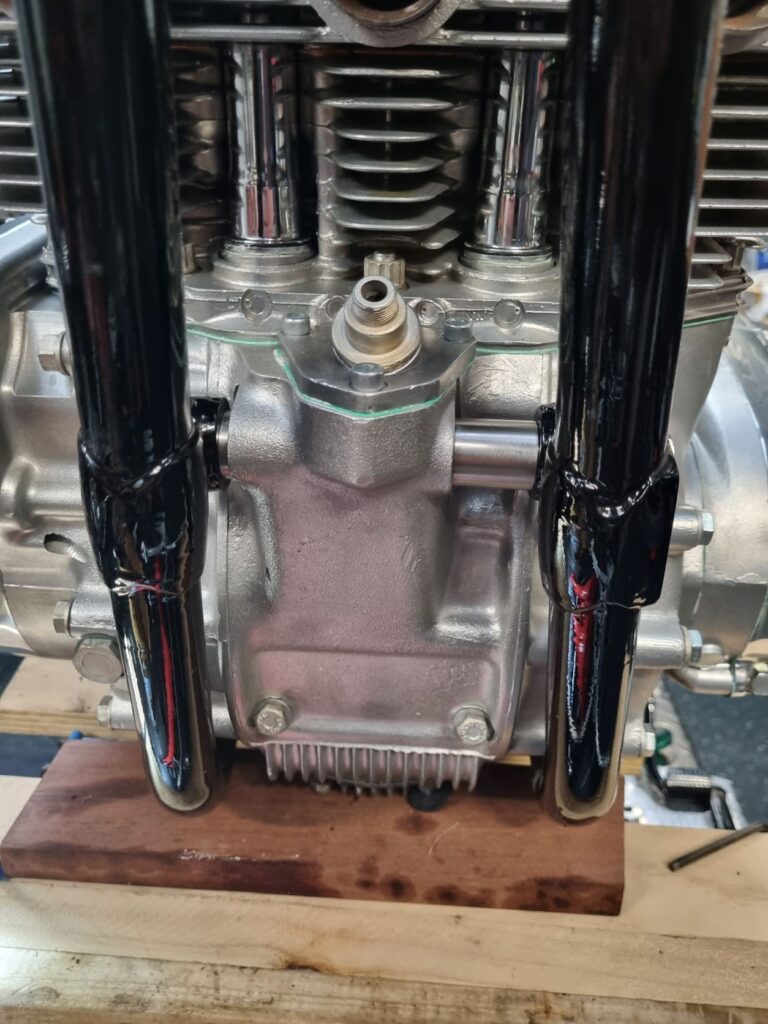

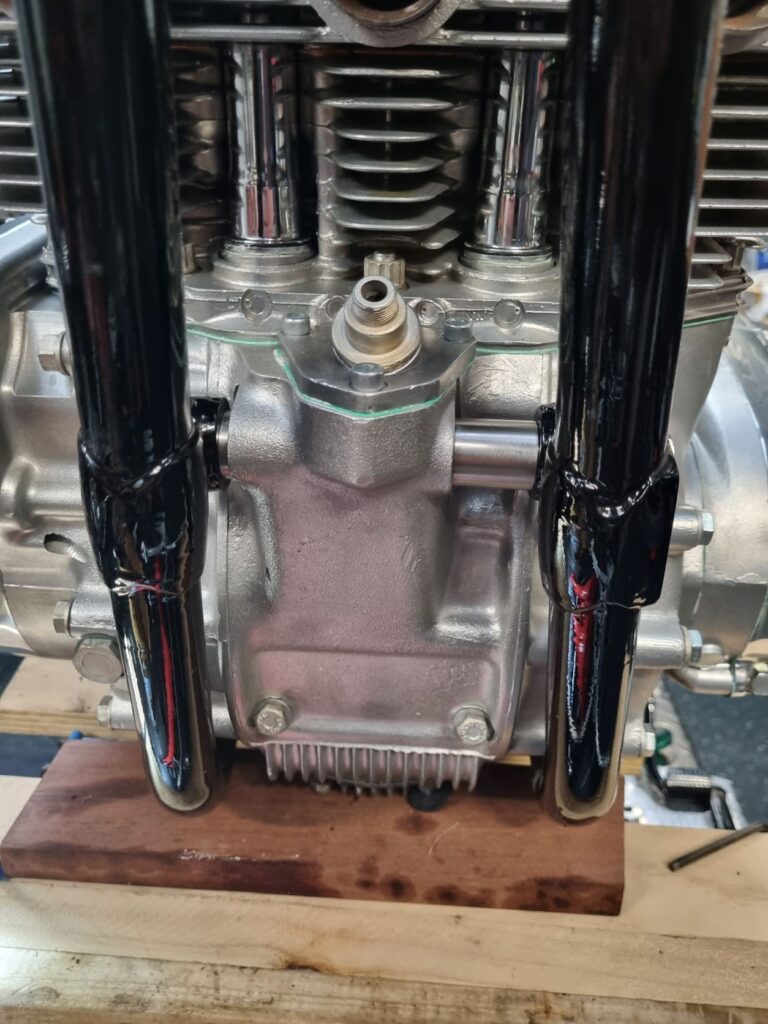

Once the engine is loosely back in the bike it must be shimmed to ensure it is in the best possible position for the chain to line up between the gearbox drive sprocket and the rear wheel sprocket. I did have shims but they were not going to line-up so I went off and purchased some 20mm stainless bar and went off to see Dave my machinist friend who turned out half a dozen shims. Another friend had sent me instructions on how to shim a BSA/Triumph triple engine which helped a lot. Essentially, there is a point at the bottom of the frame where the engine mates to lug and all other shimming must follow. After two more visits to Dave, I had the engine snug against all mounting points.

Three shims were required on the left side of the engine. All of them had to be custom made as we’re inserting a 1971 engine into a 1969 frame.

Shims at the front of the engine. Clearly, the engine is offset but I am assured this is how it should look.

The next job was fitting the wheels. I purposely left them off in case I had to approach the installation by sitting the engine on its side and lowering the frame over it. During some experimentation involving the rear brake spring, I accidently broke the alloy brake plate, necessitating a trip to a welder who was good with alloy for a repair. The hub was then sent to Perth to be refinished. Similarly, the front end could have gone more smoothly but I complicated things.

Evidently I was too heavy-handed in trying to fit a recalcitrant spring to this alloy hub. Never mind, it gave be an excuse to strip that awful powder-coating from this brake backing plate.

Now to find someone who can weld alloy.

The brake backing plate is repaired and in situ.

When BSA restyled the Rocket, for reasons known only to the designers, they fitted a sub-standard brake hub to the front wheel. The result was the earlier Rocket 3 had a superior front brake. I have obtained such a hub with the intention of fitting it to my Thunderbird. I experimented with putting it on the Rocket but it was never going to work – refer to the pictures for more of an explanation. With each change of the wheel, I had to swap the tyre over. It’s been on and off three times now so I will remain with the standard brake for now but I have been collecting bits and pieces to fit disc brakes to the machine so we will see what eventuates.

My experiment in fitting this more effective brake hub didn’t work. It is designed for use with steel fork legs. These later alloy items fouled the mounting point resulting in the air scoop pointing too high.

This is where the problem lay.

Here the bike sits with the conical brake fitted. Due to its ineffectiveness, the conical brake is often referred to as comical.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 7, 2023 | Uncategorized

Tales from the Shed: going down a VB rabbit hole

When we left last month, I had the Vincent dismantled and was feeling quite pleased with myself. If you recall I was washing a few profanities away with a couple of frosty cans of Victoria Bitter.

In my communique I also touched upon the second industrial revolution whilst heading down an internal combustion rabbit hole. Speaking of VB, rabbits and the industrial revolution, it’s timely we paid homage to the Louis Pasteur and his contribution the manufacture of Australian beers. As it turns out, Pasteur was responsible for allowing Australia’s largest brewery to export beer to the world thus the entire population could share in the aroma of subtle fruitiness complimented by sweet maltiness with a slight bitterness to finish (someone out there has just spat a mouthful of Corona over their screen).

So, what has all this got to do with classic British motorcycles? Nothing really, it’s just quite interesting.

Rabbits arrived in this country with the first fleet in 1788 but it wasn’t until 1859 that they became a problem. According to history, a British-born farmer, who wasn’t fond of the Australian fauna released two dozen rabbits, dozens of partridges and a half a dozen hares onto his land in Geelong, Victoria. By 1887 the rabbits hard spread out of control, North to Queensland and West to South Australia, prompting the NSW government to offer a reward of some £25,000 (or, $10M todays’ money) to anyone who could eradicate rabbits from Australia.

Apparently, Louis had been ill and was in need of a few francs so his wife suggested they have a crack at the prize. Louis reckoned he had just the thing, a virulent virus that would wipe out every rabbit on our island continent, but he was both too ill and too busy with things back in Paris so he sent his protégé, nephew Adrien Loir. Their intention was to use chicken cholera bacillus as the infectious agent to kill the rabbits. That’s right, they planned to eradicate rabbits with bird-flu.

Upon arrival in NSW, Dr Loir up the Australian Pasteur Institute on Rodd Island on the Paramatta River in Sydney. The experimentation was carried out under the watchful eyes of the judging committee and was expected to run for twelve months. This came as a bit of a surprise to Dr Loir who only had enough funds for he and his wife to spend a few weeks in Australia so he had to do some urgent fundraising.

Down in Victoria, emerging brewers at Carlsberg Brewery were experimenting with fermentation and sterilisation. One can imagine their excitement when they learned the father of microbiology was establishing an institute in Australia. Dr Loir was invited to Victoria where he was paid handsomely to teach the Australian brewers how to improve their product – right now some readers will be arguing the product has not advanced since 1887. Aside from refining the fermentation process, Dr Loir also taught the brewers advanced sterilisation processes which enabled the beer to be exported to the world in glass bottles.

As it turned out, Pasteur and Loir’s answer to the rabbit problem would not be released. It was thought the disease may harm the domestic avian population. Their idea also came up against opposition by wire manufactures who asserted they could stop the spread of the rodents with their rabbit-proof fences. The NSW government went with that idea but the reward was never paid out as it proved ineffective.

So there you have it, the machinery of the Busted Knuckle Garage is lubricated by the fruits of French scientists Professor Louis Pasteur and Dr Andrien Loir.

Now, back to work, that Vincent is not going to put itself together.

Cheers

by Dan Talbot | Feb 1, 2023 | Uncategorized

Tales from the Shed: let down by a ten-cent seal

This piece has been written by me for inclusion in Classic Vibrations, the magazine of the Indian Harley Club of Bunbury, Western Australia.

Newton’s third law states for every action in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction in force. Let’s look at that. A piston, for example, converts chemical energy to kinetic energy and through a series of mechanical interactions transfers that energy to the road where it propels the operator forward. For the kinetic energy to get to the road, there is a multitude of equal and opposite reactions that are mostly protesting and working against forward momentum. These mechanical devices, for the purposes of this communication let’s call them motorcycles, have reached incredible levels of sophistication and reliability yet some of us, in fact most folk reading this I suspect, have an unusual attraction to motorcycles from the last century.

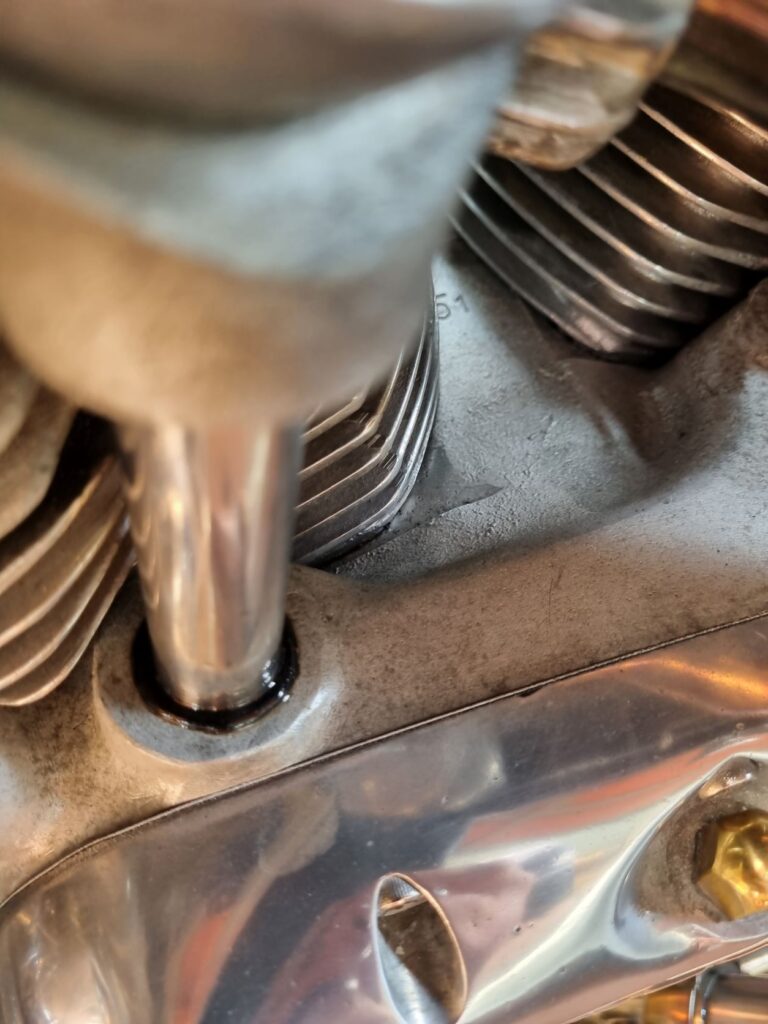

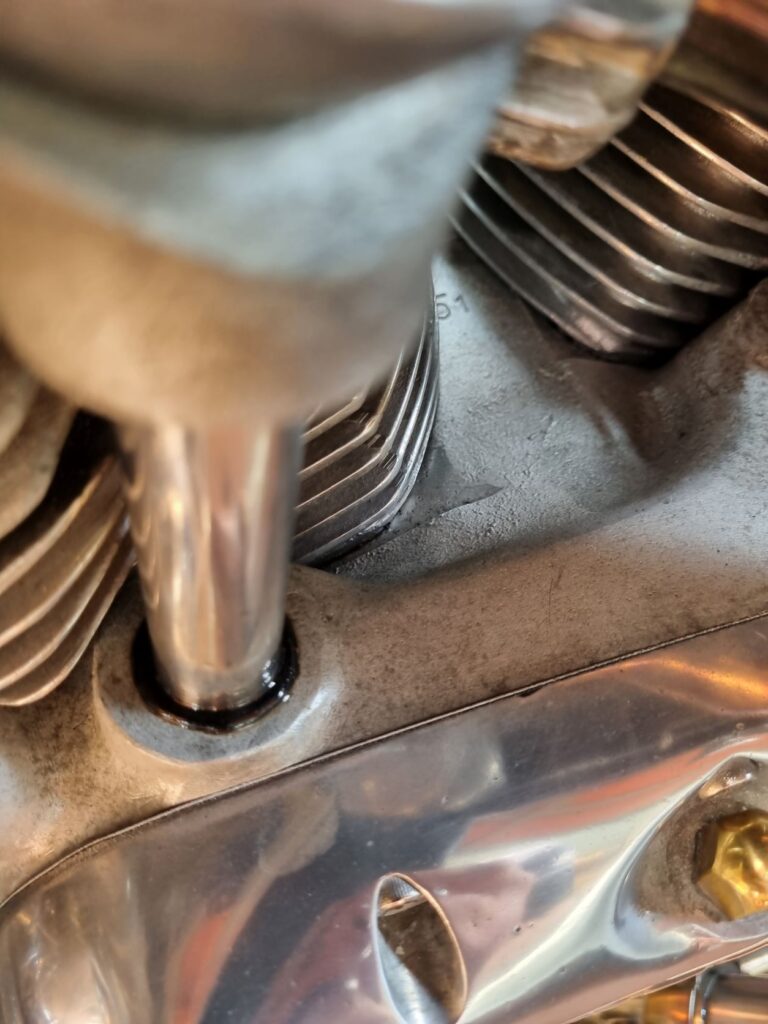

It looks innocuous enough, but this small trickle soon turned into an oily torrent.

We have a love for classical machinery that requires a deft ability on behalf of the operator to continue converting energy to forward propulsion in a variety of challenging conditions. For me, whilst I am cruising happily along on my classic motorcycle the world is a beautiful place. My machine is a valuable and prized example of the second industrial revolution. However, when that machine fails, it can quickly become a cantankerous and unreliable old bike. As happened recently.

I had been very much looking forward to the Australia Day run out of Boyanup. Being a combine event, I was equally looking forward to bringing my classic Mustang as well as my Vincent so some juggling of vehicles between home and Boyanup was required. Just to back-track slightly, on the Sunday before Australia Day I rode the Vincent to Mandurah to meet up with the Mob up there and joined them on a coffee run up into the hills. I have been aware for some time a pushrod seal on the Vincent were seeping oil and I have attempted makeshift repairs by wicking silicon into the aging seal and round the tube. But the equal and opposite forces could not be kept at bay and by the time we arrived at Dwellingup I was leaving embarrassing amounts of oil wherever I parked. I was 100 miles from home so both a clean-up and top-up were in order. Arriving home, I wicked more silicon into the offending seals in the hope I could stem the flow and make the Australia Day ride few days later. Alas, I couldn’t.

To get to the seal, the push rod tubes must be removed. To get to the push rod tubes the heads must be removed. To get to the heads the upper frame member must be removed ….

By the time I arrived in Boyanup on the Wednesday before Australia Day the Vincent had a coat of oil down the right side. Oil was migrating to the rear tyre so the machine was parked up and my Australia Day was thereafter confined to four-wheels. Sure, I have other bikes but my bottom lip was well and truly on the ground and I was not prepared to countenance another machine.

In the days following the ride, I licked my psychological wounds and retrieved the bike. The IHC Two Day Rally is fast approaching and I cannot ride the Vincent in the event in its current state so I had to get straight into it. I had contemplated handing the machine over to someone a little more skilled in Vincents than I but I was assured taking the heads of a Vinnie is no more difficult to those on my Triumphs or Ariels, so I dived in.

The offending seals are about the same size as a wedding ring. A ten-cent band of rubber that is easily popped out by the fingers once the pushrod tube is removed. The problem arises in removing the pushrod tubes for, to do that, the heads must be removed and, to do that, the front half of the frame must also be removed. It’s a massive job to get to four dinky little seals.

With the fuel tank off, the upper frame member is clearly visible. This needs to be removed, along with the front end to allow one to remove the heads.

I have mentioned a frame, but Vincents don’t have a frame in the normal sense of the motorcycle world. They have an upper frame member which bolts to the top of the engine and carries the girdraulic front forks, and a rear frame member which is basically a triangulated swingarm that holds the rear wheel and is bolted to the rear of the engine. The engine is essentially part of the frame: everything hangs off the engine.

This is it, a lot of work to get to the offending seal.

Things get a bit tricky removing the upper frame member because carburetors, electrics and cables all need to be removed or otherwise taken care of. Cleverly (or infuriatingly if one has to remove it) the upper frame member is also the oil tank so that has to be drained too. I must say, I found the dismantling the machine an enjoyable few hours in the shed. Sure, the neighbours heard the odd swear word but, by and large, things went quite smoothly. As the sun was dipping into the Indian Ocean just across the park, I rewarded myself with a couple of stubbies of Victoria Bitter. Sitting there, sipping one of Australia’s finest ales, I reflected on the beauty of the Vincent design.

The push rod tube. The top part is secured into the head by the gland nut, whereas the lower section simply pokes through the seal.

The synchronicity from the front wheel, through the engine to the rear of the machine almost punches you in the face (or perhaps that’s the VB). If we can go all Newtonian again, Phil Irving, the designer of the Vincent engine, knew exactly where the forces of mechanical design would work, and where they would fail. Now that I have the motorcycle apart, I can see his thesis laid out before me and it is brilliant. Let down in this case by a 10 cent rubber seal which bears a quite unequal relationship with the energy inherent in a 1000cc V-twin engine.

And now we wait for parts to arrive ex-East.

by Dan Talbot | Mar 23, 2022 | Uncategorized

Back in October last year I helped out as a marshal at WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally hosted by the Indian Harley Club. I enjoyed my roll as Clerk of Course, not least because I got to spend a whole week touring the South West of Western Australia on my ’48 Vincent HRD – which is by no means a veteran motorcycle.

Subsequent to the event, my friend, and fellow IHC club member, Des Lewis released a very good quality video of the rally (WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally 2021 – YouTube). Such is Des’ prowess with the camera, at the end of his video, my wife turned to me and said “you should get one of those.” “Okay, challenge accepted.”

Veteran motorcycles rarely come up for sale and, when they do, they generally cost a few bob. An added complication is I have a particular hankering for a v-twin. The ones I have gravitated towards start at about $75k (AUD) and go up from there. It may surprise a few readers that I don’t have a lazy $100k waiting for the right veteran motorcycle to come available. I do however have the connections and ability to rebuild a project machine. A machine that will still start at about $20k for a v-twin. If I am going to get onto a veteran Excelsior, Yale or Pope, I will need a fairly decent starting wedge. I will need to sell something. I resolved to swing back to the Rocket 3 project (part 1 can be viewed here and part 2 here). That job has been parked up whilst I have been busy elsewhere. The fly in this ointment is: I am telling myself this is a rebuild that will be offered for sale.

Long before Triumph named their 2.3 litre behemoth the Rocket 3, almost 6,000 BSA’s Rocket 3 motorcycles had made their presence felt on the racetrack and in the boardroom. These bikes were manufactured from 1968 to 1972. Their Triumph stablemate, the Trident, lasted a little longer into the mid-seventies.

My once grand 1971 Rocket 3 came to me as basket case of forgotten dreams. A relic of its former self, certainly not something befitting the victory in the 1971 Daytona 200 or the machine that was able to conquer Agostini’s MV at Mallory Park in the same year. Two frames were thrown into the deal, from which I was be able to salvage one. The bike had clearly been crashed, big-time. Despite being an obvious write-off, the assembled parts arrived in Australia with a title and import approval. It had been uncovered by a friend who lived and worked in the US for about seven years. Like me, Steve has an unhealthy attachment to triple cylinder British bikes, namely, Triumph Tridents and BSA Rocket 3 cycles. Every time Steve saw a triple come on to US the market for under $2,000USD he would snap it up. During his seven years, Steve amassed some 14 motorcycles, two of which now reside in my shed (you will note I’m referring to the basket case Beeza as a motorcycle). Alarmingly, he still has a container full of bikes in West Virginia awaiting dispatch to Australia, some of which will no doubt end up my shed. Back to the pile of rubble.

During some cut and tuck between the donor frame and the crashed one, we had cause to cut the head stock from the frame. Only then, one can see how thick the metal tubing is. It’s massive. Looking again at the bent tubes and thinking about the forces that would be required to bend it are a little bit mind boggling. I doubt the person who crashed it would have survived. There was some serious impact there.

Two frames become one. Note the bends around the head stock. This frame should have been grey, instead, it had been repainted in a blue metallic finish. It also had the two down tubes replaced at some time, causing me to suspect it had been crashed twice.

The repaired frame has been resprayed in a lush black paint. I did consider powder coat but paint much closer resembles the original without the chunky, plastic-coating quality powder coat produces. Whilst the frame was in the paint shop, I turned my attention to the guards. The later Rocket 3 incarnation, starting in 1971, has acres of chrome, including the tank and guards. The chrome and bling came out of BSA Triumph recovering from a design misstep. Actually, history shows there were quite a few missed steps.

During the frame reconstruction, we had cause to cut the top tube. This is how thick in is!

The BSA and Trident 3-cyclinder, 750cc engine is almost identical. The engine was originally a Triumph design however, BSA had acquired ownership of Triumph a dozen or so years earlier and, whilst they were separate entities, operating out of separate premises, BSA decided they wanted a piece of the triple action. Prototype machines were being tested in 1965 and could have gone into production for the 1966 model year. Simple badge-engineering should have done it however, not content with sharing the design across the two brands, BSA insisted on making a triple of their own and this is where things get a little ridiculous. The Triumph triple cylinder engine was built in the BSA factory at Small Heath, it was, for all intents and purposes a BSA engine. In following naming conventions of the day, engines destined for Triumph were stamped with the prefix T150. BSA engines were stamped A75. That’s easy, no problem there, except to see the difference between the engine prefixes one almost needs to get down on the ground to read the stampings.

The engine that started it all: the Triumph T150 750cc triple. Designed by Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele. Photograph supplied by Leonard Johnson.

It was decided the BSA engine would need a distinctive look so the barrels on the BSA unit were canted forward by 13 degrees, which (kind of) dissociate them from Triumph. The right-side timing and gearbox outer cases were also altered to provide another individual touch to the BSA item. Think of designing something that is basically the same yet requires re-tooling, casting, machining etc and the simple act of making minor changes becomes a major undertaking. Luckily, the internals remained the same between the two engines, as did just about every other piece of the triple.

My BSA Rocket 3 engine prior to stripping. Although not immediately apparent, the barrels on this engine are canted 13 degrees forward (as opposed to the Triumph T150 engine). Subtle changes to the timing case are also evident, otherwise both engines are essentially the same.

With the engine (almost) uniquely styled to BSA, it became apparent the Triumph duplex frame would not support the forwarded slanting engine so the BSA would need a new frame too. Conveniently, Triumph would later use the same set up to allow inclusion of an electric start behind the barrels of their 1975 T160, which would become the last of the triple cylinder Triumphs.

The finished product would add two years to the release of both bikes and BSA Triumph missed the opportunity to unleash the first mass-produced, multi-cylinder superbike onto the world market. Instead of releasing their world-beating machine in 1966, it was released in 1968, mere weeks before Honda came along with their new 750/4. The Honda Four was almost as fast as the British triple but was less expensive and would prove to be more reliable than the BSA Triumph offering. The Brits had been caught resting upon their laurels. They were the motorcycle super-power of the time and probably expected to remain as such. As touched on earlier, Triumph and BSA triples went of to win production racing around the world, including the two most famous races of the time, the Isle of Man and Daytona. BSA dominated the American AMA competition well into the 70s but sales of the Japanese bikes sored, whilst sales of the British machines stagnated. Aside from the expense of the British machines, they had a distinctive style that did not go over well with the buying public.

To celebrate the release of the new machines BSA/Triumph engaged Ogle Design Company headed by David Ogle. Ogle Design were known for creating the Raleigh Chopper bicycle, toasters and an odd little three-wheel motor car by the Reliant Motor Company. In 1968 they entered the two-wheeled world when contracted by BSA/Triumph to put the finishing touches to their new triple cylinder motorcycles. It was a disaster. The famous lines of the Triumph twin, one of the most iconic motorcycles of all time, were lost. In its place was a slab-sided fuel tank, massive side covers and futuristic mufflers – referred to these days as ‘Rayguns.’

The Ogle Designed first incarnation of the BSA Rocket 3. Quirky at the time of release, these machines are now highly sort after.

Note the ‘Raygun’ exhaust. Considered a bit odd at the time of release, there mufflers are now very much sort after. Photograph by Tim Hesford.

The new machine was a hit with road-testers and racers but it failed to win the hearts and minds of Triumph owners, and potential owners. Motorcycle journalist Bruce Main Smith described the Rocket 3 as: “Biggest and most beautiful hunk of reciprocating machinery ever built.” It would take two years before the Ogle hoodoo could be undone and BSA/Triumph returned to the tear-drop tank, high bars and megaphone style exhausts. The new machines were released in 1971, predominately to the US, gaining unofficial title as ‘Export’ models. It is this variant of the BSA Rocket 3 that I am bringing back to life.

By 1971, BSA Triumph began to offer an alternative version of their machines designed to appeal to US buyers. The machines were dubbed ‘export’ models. This motorcycle is owned by Warren Hodder in New Zealand. The photograph has been supplied by Warren Hodder.

Note the Dove Grey colour of the frame. This wasn’t received all that well and by the end of ’71 BSA had gone back to a black fame. Photograph by Warren Hodder.

As each gleaming piece returns home and is stored or, in a few cases, refitted to the bike, I become just a little more attached. It’s like getting a kitten. The attraction is based first at a cute, superficial level but grows each day until the kitten becomes a cat and is loved very much as part of the family. Similarly, the BSA is starting to edge its way into my heart. It is going to be a special motorcycle and, as such, I throw only the best quality parts at it, such as forged steel conrods and chrome-plating that seemingly has no end. I could get cheaper, knock-off items from India but I want to retain the original items, even if it is more costly (just in case I end up keeping the bike).

Paying for the re-plating of a motorcycle that was lavished in chromium is arduous. I send parts to the platers piecemeal, so as not to shock the wife with too large a debit in our bank account. The guards cost $500 to replate. It sounds like a lot of money but the finished product is magnificent. The new chrome guard tucked in the black frame looks splendid. The next instalment of pieces for the chrome-plater are on their way.

Also on their way to the platers are all the fasteners and ancillary pieces that I had previously re-finished in zinc. This was a mistake. As the project has been parked up for a couple of years the zinc has discoloured and cannot be put back on the bike in the present state. I will now have them re-plated in cadmium (like I should have done in the first place).

This lot are going back to the electroplaters to be redone in cadmium. Which I should have done in the first instance.

On a final note, and going back to chrome, the Export model fuel tank was chromed and painted – not unlike the Ariel I have just finished and reported on in last month’s Classic Vibrations. Organising a union of chrome and paint is difficult in WA. Platers charge enormous amounts and they can take months to be finished. For some years, whenever I’ve needed chrome and paint, I visit John Berkshire, the former owner of Vintage and Modern Motorcycles. Vintage and Modern had a premises in the same block of units as K & D Metal Finishers and John has maintained his connection with Kerry from K & D. The result being, I have a one-stop service that turns out first-class paint and chrome products. To this end, I now have a beautiful orange and chrome tank waiting to go back onto the motorcycle.

The second lot of chrome has been completed. The first being the fuel tank, the third lot was the guards and the fourth is about to be sent off to the electroplater.

The fourth, and hopefully final, lot of parts are off to be re-plated. In most cases these items could be obtained as reproduced pieces out of India but I feel better using the original items – even if it does cost a bit more.

Fresh chrome on lush, black paint.

Special thanks to Tim Hesford, Warren Hodder and Leonard Johnson for supplying photographs of their motorcycles.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 21, 2022 | Uncategorized

When we left the Square Four project last month, she was about to be reduced to hundreds of pieces. A lot of those pieces necessitated individual decisions on preservation, restoration or substitution. Preservation is good. I use the term here to simply indicate a clean and polish then set the part aside to be reunited with the motorcycle at some later point. Stainless steel, alloy and brass components come immediately to mind. Restoration is more complex. It includes machining, painting and plating. Substitution is a murky swamp with quicksand just below the surface. Your hand can disappear into this mire with a wad of money, only to come out covered in regret.

Before we go any further, please note, this is not a treatise on motorcycle restoration, it is an informal collection of loose threads that includes some of the highs and lows of such a project. I’m happy to say the lows were kept to a minimum, due in a large part to the previous owner’s deft mechanical skills, for example, the engine was running sweet and strong so there was no point in pulling it apart this time round. But it did look quite grubby so I was compelled to give it a clean-up. I thought I would use baking soda and give it a blast. That’s mistake number one. Mistake number two was attempting to hose it off with water.

My first attempt at soda-blasting didn’t work out so well.

I’m not sure where I picked up the idea to clean the engine with a soda-blast but the end result was a white compound caked into the most inaccessible parts of the machine. I’d made a hideous mess of it. Fortunately, in the back of my mind I knew the bike would be coming apart and having it covered in the dirty white discharge of Frosty the Snowman only served to hasten the pull down.

The pull down on an old British motorcycle can be a messy affair (primarily as they are known to lose a bit of oil) but, remember, grease and oil preserves metal and whilst having your arms covered in black grime is inconvenient, the motorcycle can be remarkably well preserved below the crusty exterior. An acid-bath and cadmium plating will have even the grimiest fasteners looking like new. Better still, you can replace them with stainless steel.

Stainless is an extravagance reserved for the rich or foolish, and I don’t have a great deal of money. There is a lot of hardware at the rear of an Ariel that can be placed by stainless steel. I was introduced to the work of Mr Clay Jones, a UK-based gentleman who owns an Ariel, as did his father before him (sounds familiar). Clay trades under the name of ‘Acme’ stainless steel and writes, “we strongly believe that is not our place to change history and therefore we machine out parts to the correct profile of genuine and original parts we have sourced from and customers over the years” (Acme Stainless). Once you’ve seen Clay’s high-quality pieces fitted to an Ariel it’s hard to contemplate using anything use. Cad-plated steel will not hold the same allure. To this end, I spent and enjoyable evening some 18 months ago loading my virtual shopping cart with an assortment of Clay’s finest machined Ariel parts. I’m happy to say the goods arrived safely in Australia and are now festooned around my motorcycle – it’s the best $1,000 I’ve ever spent on nuts and bolts.

Armour Exhaust and Acme Stainless Steel are two excellent British companies churning out high-quality spares for the motorcycle restoration market.

Some of the stainless steel fasteners I received from Acme in the UK. Beautiful stuff.

Speaking of securing UK hardware, there’s some fine specialist manufacturers at work over there. Armour exhaust delivered a complete four into two exhaust system, manufactured and chromed in the UK, to Australia for less than the price of having the old one re-plated here. The work is first-class and fits perfectly. Unlike a lot of the products coming out of India. Which brings me to the Indian product. Reproduced motorcycle parts out of India is a massive industry.

Recall my previous discussion about reverting to a sprung saddle? The accompaniment to that is a fuel tank from the era. The era was paint and chrome with a large brass cap at the top and an oil-pressure gauge holding court in the middle of the tank. The oil-pressure gauge is a particularly nice touch. It begins to bump up the scale with a few prods of the kick-starter. During times of recalcitrance, I can generally get 50 psi out of half a dozen swings on the kick-starter. Ernie had fitted a Repco-style gauge to the handle bar but the modern instrument looked way out of place. However, having lived with the security of an oil-pressure gauge on a vintage motorcycle I really couldn’t live without one, so I sourced a period-correct, Smiths item from Gumtree. Evidently it was out of an old Jag but it looks perfectly at home on the Ariel. Now, back to the tank.

My Indian-made, chromed and painted fuel tank arrived at my door in rural Western Australia for under $500. It’s a very good piece of work.

I had obtained an earlier Ariel fuel tank but it was too far gone, the swamp swallowed $400. I then took another gamble on an Indian tank. This time it paid off and for less than $500 Mumbai’s finest manufacturing has curried favour with Turner’s creation (there goes another mouthful of the purist’s dark ale, all over their computer screen). The chrome and paint are first class but the tank did leak when fuel was added. An epoxy liner has plugged up the leaks and I now have a gleaming chrome tank, with black inserts and gold pinstripe. The polished brass fuel cap sets things off nicely.

By the nineteen fifties, brass was so last year. It was associated with old vehicles so manufacturers went to great lengths to cover it up, lest their product looked old. These days, when I notice there is brass under rusty chrome, I do a happy dance because I know it’s going to add a golden touch to my machine. Ariel fuel caps are a complicated, three-piece, item that is made of brass and looks splendid when stripped of the chrome.

Stripped of chrome, brass shines like gold.

One of the most important things I do when rebuilding a motorcycle is to upgrade the electrical system. The Ariel was no exception. Elsewhere in my shed, Trispark electronic ignition and a modern BTH magneto reside in my Vincent and Triumph respectively. They provide healthy sparks through iridium plugs and give me great peace of mind. In the case of the Ariel, with its Lucas distributor borrowed from an Austin, I was forced to turn to car mechanics for increased reliability. This included changing my old 6-volt system to 12-volts and sending my aging dynamo to England to have the guts changed out for a 12-volt, 300-watt Nippon Denso alternator. There was no replacement unit. One must retain one’s own unit because, in their wisdom, Ariel put the distributor right through the end of the generator. Anyway, Bennet Longman of Iron Horse Restorations does a marvellous conversion and now I have enough electricity to power a small town.

My Iron Horse alternator conversion in situ. Note the provision for the distributor drive at the right side of the unit.

Bennet asserts a lower kick speed will fire up the engine and, once running, the alternator will balance the charge of the ignition system and modern 12v headlamp bulb at around 25mph. He also bench-tests each unit before it is returned. Back home, during an early test run, and having muddled up the wiring, my kill-switch wouldn’t shut the engine down so I disconnected the battery however the bike continued to idle, powered only by the alternator. I’m guessing it will balance the charge system from the get go.

Another item, which would have been novel in 1954 but not so much these days was the inclusion of an oil filter. I used one that was originally made for a Citroen 2CV. It seems these items are being churned out (again, most likely in India) for use in the motorcycle industry. Back in the eighties I spent some time travelling through Europe with a German in her 2 CV, our lubricant of choice was pilsner (we’ll leave that right there as this is family-friendly forum after all).

The oil-gauge taking centre-stage is a welcome addition to a vintage motorcycle. This one was sourced from an old Jaguar motor car.

Back to mineral oil, and the evolution of the internal combustion engine, Doctor John Ellis, decided crude oil would likely be better at reducing friction than lard, which was the lubricant for most of the 19th century. Dr John was onto something and mineral oil became the saviour of moving parts everywhere. During the early part of the 20th century, dumping oil onto the earth was becoming uncool so engineers started to turn their efforts towards saving and cleaning the engine oil. Oil tanks became a thing and gravity aided in keeping the circulatory system clean with the heavier particles sinking to the bottom.

The oil filter has been borrow from a Citroen 2CV. I’ve tucked it away in the tool box because, after all, who needs tools when you’re riding an Ariel?

Another way of removing contaminants from oil was to centrifugally trap it. Of course, the main centrifuge in an engine is the crankshaft, so early engineers resolved to filter oil in the deepest, hardest to get at part of the engine. To assist mechanics keep these troublesome journals clean, a tube was inserted into the middle of the crankshaft, its sole purpose being to catch particles and grime. These tubes are called sludge traps and they do an excellent job of trapping circulating debris. Eventually, when they’ve caught enough, nothing will get through the journal, oil will cease to flow and the engine will explode, or best case scenario, it will grind to a hault. So here’s a tip. Should you buy an old bike, see if you can find out the state of the sludge trap. My ’56 Thunderbird looked brand new when we got it. Ten years later, I had cause to pull the engine down and a significant amount of sludge was removed from the crankshaft. Disaster averted.

Gunk pulled from the sludge trap in my ’56 Triumph Thunderbird.

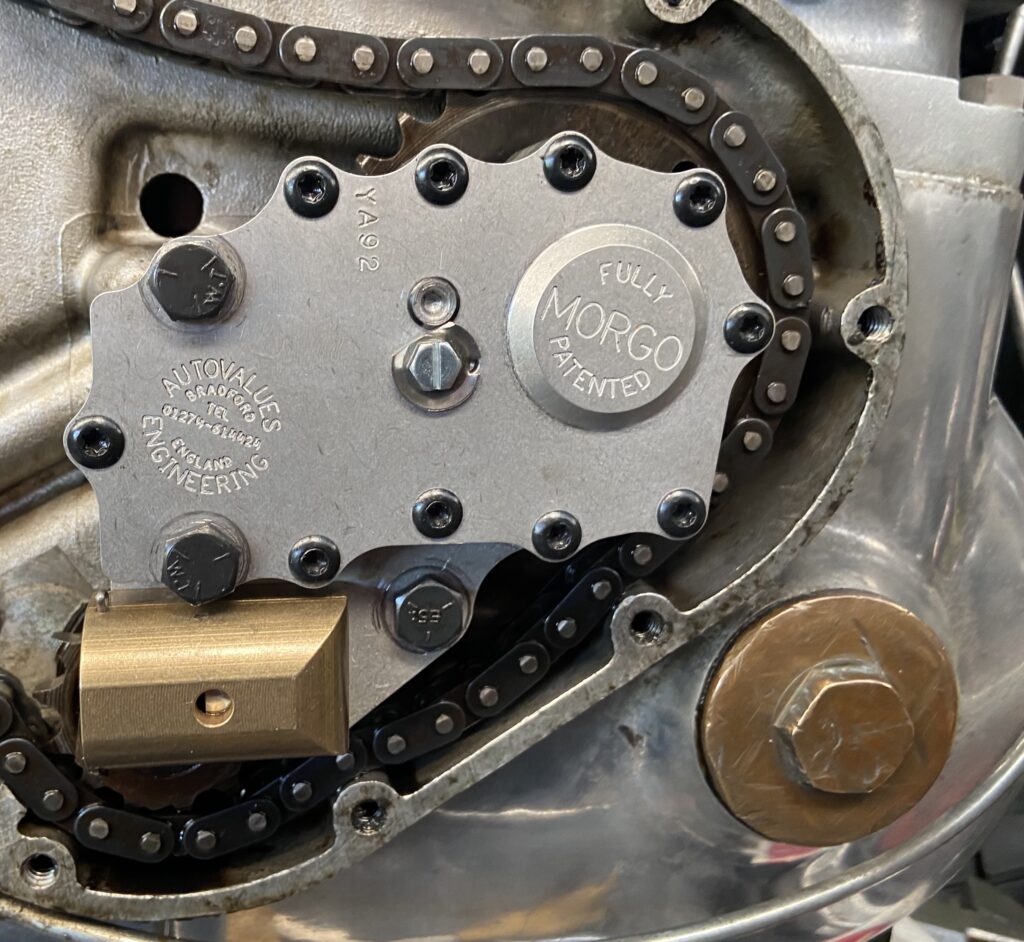

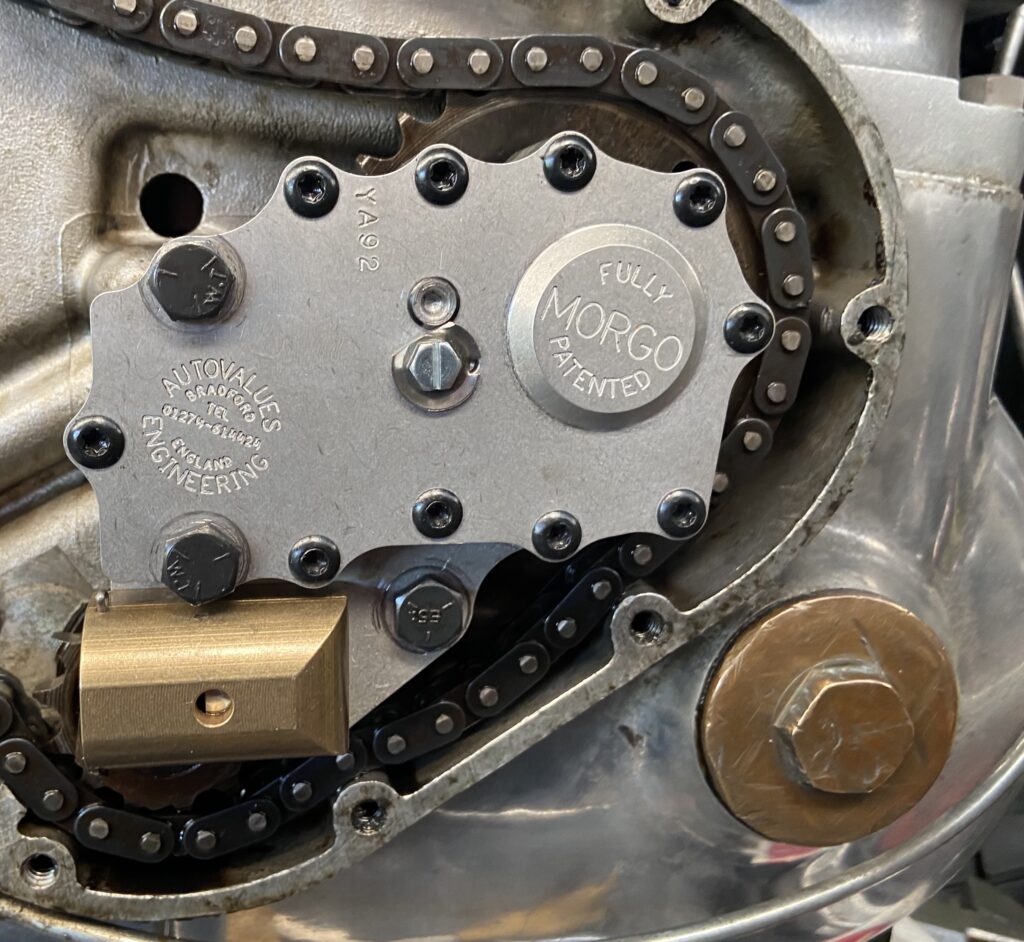

The Ariel remains an unknown but I do trust the previous owner’s judgement and hope there’s not too much gunk in the two cranks. In the meantime, I am hoping my nearly fitted oil filter, a powerful new Morgo oil pump and some good quality detergent oil will help clear the plaque from the arteries of the Square 4 engine. For me, a good oil pump is de-rigueur and the best for British motorcycles is the British made Morgo. In 2019 I visited the factory to pick up one of their big-bore kits for a Triumph and I must say I was very impressed with their outfit. The downside is demand often relieves Morgo of stock and you need to go on a wait list until they do another product run. But it is worth it, a good circulatory system is crucial to the wellbeing of multi-cylinder engines, any engine in fact.

The original Ariel oil pump was removed and replaced with a modern Morgo rotary pump.

The Morgo rotary oil pump is a modern, reliable piece of equipment that has been used in many machines in my shed.

So, there you have it. Everything old is new again. Ariel’s attempt at post-modernism didn’t really work for me (nor did BSA/Triumphs for that matter), so I’ve taken the machine back to its roots. There is another longer story out there about the Ogle-designed Triumph Trident and BSA Rocket 3 of 1969. They were fine machines but, in terms of sales, they flopped. The Americans were having none of it and BSA/Triumph were forced to revert back to the more traditional lines and classic fuel tank in what became colloquially known as ‘export’ models. I’m sure, had Ariel remained liquid, they would have done the same thing. In this case I’ve done it for them, successfully – if I may be so bold.

Now, I must go and sift through my slides for one of a Frau and her quirky little French car.

Aside from stainless steel, regular items look new again with a good coat of cadmium.

Paint, powder-coat, chrome and cadmium. Everything is either painted, polished or plated.

Back home and ready to go back onto the Ariel.

Rewards in stripping off a bit of paint are evident.

by Dan Talbot | Jan 8, 2022 | Uncategorized

The Lord’s Motorcycle

By Dan Talbot

For many, the name Hesketh would be quite alien as a motorcycle brand. Certainly, it’s hardly synonymous with motorcycling and I suspect a good many people reading this are not even aware there was such a brand. Hesketh Motorcycles was a company created by Lord Thomas Alexander Fermor-Hesketh, the 3rd Baron Hesketh, and followed his semi-successful Formula One racing team. At a time when the sun was setting on the motorcycle production in the UK, it was Lord Hesketh’s intention to revitalise the industry. His progenitor for this was an audacious 1000cc V-twin sports touring cycle reminiscent of Brough Superior and Vincent.

By the late seventies, the last manufacturer of British motorcycles, Norton Villiers Triumph, was in its death throes with aging designs and sketchy manufacturing practices. The fathers of the industrial revolution were losing the fight against an onslaught of superior machinery out of Japan and Europe. Throughout the seventies I witnessed British motorcycles winning on the race tracks and the streets. When it came time to purchase my first big road-bike it was no contest, it had to be a Triumph. In fact, by that time, if I wanted to ride a new British motorcycle it could only be Triumph or Norton. Many of my friends were riding Honda 750 and Kawasaki 900 machines but they didn’t appeal to me as much as a 750 Triumph Bonneville. To ride a new British motorcycle I was limited to 750 and 850 parallel twins, but, unbeknown to me, plans were afoot in Northamptonshire, England, to re-introduce a British V-twin to the world and re-stablish the Brits as the superpower of luxury motorcycles.

As the kernels of Hesketh Motorcycles began to take hold, some journalists were touting to reintroduction of the Vincent twin. This excited me no end. Regular readers will be aware of my life-long love-affair with the marque and to be able to purchase a new Vincent in 1980 had me ready to sign up. As it transpired, artist’s impressions of what Hesketh might look like bore little resemblance to Vincent and nothing like the machine that was eventually released. At the end of the day, all Hesketh had in common with Vincent was exclusivity and expense, however, unlike Vincents, the Hesketh was plagued with problems.

What’s not to love? A chook’s head as your official logo. Lord Hesketh may have fancied himself as a bit of a Rooster.

The Hesketh was released with a stonking 90-degree V-twin engine. It needed to be substantial as the engine made up the lower part of the frame, in what is commonly referred to as a ‘stressed member.’ At 90 degrees, it looked more like a Ducati than a Vincent or Brough Superior. The engine was a gleaming lump of alloy (destined to devour many a tube of Autosol), part of a handsome machine but one that would not find its way into my heart. By the time the Hesketh was released to the world I had gone down the Harley route and I was firmly entrenched in the American cruiser culture (in my defence, I was young and impressionable. I did however keep an eye on Hesketh, more so out of curiosity than anything else. I was disappointed to learn early examples were beset with problems. We’ll get to the problems – and to how they were fixed – soon. In the meantime, it is useful to review the V-twin engine.

For a long time, British twins were of the parallel variety, where cylinders are placed side by side and fire evenly at 360 degrees in each 720-degree cycle. By placing the cylinders 90 degrees apart, different firing patterns are adopted. A 90-degree v-twin engine will fire at 270 and 450 degrees within the 720-degree cycle. Where the cylinders are arranged 45-degrees apart, the engine will fire at 315 degrees and 395 degrees in 720 degrees. The odd firing patterns of V-twins suggests they run less smoothly than the evenly-spaced, 360-degree parallel twin, which is not so. In the parallel twin, both pistons are rising and falling together, creating reciprocal forces that play out as vibrations through the handle-bars, seat and foot pegs. By contrast, in the 90-degree engine, where the pistons are rising and falling independently of each other, reciprocating forces are lessened. Furthermore, when one piston is firing, the other is travelling at full-speed which tends to balance vibrations rather than create them. Hesketh was wise to employ the 90-degree layout.

Unlike Vincent and Brough Superior, Hesketh emulated the Italians with a 90 degree layout. This engine was salvaged from a machine that was lost in the 2003 National Motorcycle Museum (UK) fire. The engine later found it’s way to Western Australia were it was on display in the York Motorcycle Museum for many years.

Generation one of Hesketh Motorcycles ran from 1980 to 1982. Unable to raise sufficient capital for his creation, Lord Hesketh injected his own funds into the venture but the company ultimately failed. The idiom “creating a small fortune from a large one” played out and by 1982 Hesketh motorcycles fell into receivership with just 139 ‘V1000’ motorcycles being produced.

An early Hesketh V1000. Picture supplied by Mick Broom.

In 1983, with a little help from his friends, Lord Hesketh formed Hesleydon Ltd and had a brief return with another 40 machines, dubbed the Vampire, being produced. By this time, it was well known the motorcycles were afflicted with a variety of problems, not the least of which included; excessive piston clearance (okay ‘slop’), excessively hot rear cylinder and leaky cam-drive case. The marque once again closed its doors. But the story doesn’t end there.

Mick Broom was a development engineer with Hesketh and was intimately acquainted with the engine and the gremlins that lived within it. Furthermore, Mick knew what needed to be done to improve rideability, reliability and longevity of the motorcycles but he was fighting against the winds of a corporate economy that insisted on selling underdeveloped machines, at extraordinary prices, to the public. We’ll let Mick take up the story.

“The obvious question arises, why did a new motorcycle fresh from a factory require all this work after being sold as a up market quality product. The short answer is lack of adequate funding which led to lack of resources and the factory being forced into decisions based on survival with very great pressure from all to deliver bikes. Added to this was the fresh problems due to the different parts and assembly method used at the factory and the ultimate inspector/tester the customer entering the arena and the result was interesting to say the least, for those who lived though it (Broom, 2021).”

As well as a Hesketh engineer, Mick Broom also raced one. This picture comes courtesy of David Sharp and was taken at Silverston in 1987.

After the demise of both Hesketh Motorcycles and Hesleydon Ltd Mick continued to improve the motorcycles with engines being sent to his base in Easton Neston, Northamptonshire. Broom’s improvements were referred to as EN10, a contraction of Easton Neston 1.0. They were, by all accounts a huge success. Writing in the Classic Bike Hub in 2012, Mike Lewis describes the EN10 improved Hesketh as a “Revelation. Gear selection is slick and precise, the meshed cogs remaining silent even at very low revs. A big handful of midrange throttle in top gear brings up 100mph at just 6000rpm.” Lewis goes on to make a clear observation in that without Mick Broom Hesketh would merely be, “at best, a short-lived historical (motorcycle) footnote.”

Mick’s company, Broom Development Engineering, acquired ownership of the Hesketh names and continued with his EN10 modifications. Broom had the capacity to produce up to 12 complete motorcycles a year, although, in his words, “I had the capacity to produce 12 a year but some years I never made one, most of my work was in (EN10) updates.” Mick’s updates included taking delivery of an engine, removed from the host machine and fixing items such as oil regulation, engine breathing, cam chain-case re-engineering, re-machining the bearing mounts within the crankcases. Obviously this is quite an extensive list. In correspondence with the author, Mick said, “One thing you learn very quickly in the development game is that when you have solved ‘ the problem ‘ another will take its place. This chain will only end due to an unrelated, in engineering terms, factor. Very simply our job is to make a mechanical assembly perform better by removing the weakest link, this then exposes the next one and off we go again, usually until the money runs out or we achieve our goal.”

Mick Broom achieved his goal. He has taken just about every early Hesketh and improved the engines to the point they are now reliable, ridable and collectable motorcycles. Mick sold his stake in the company in 2010 and since then Paul Sleeman has built a very limited number of large-capacity V-twin motorcycles carrying a 1920cc S&S engine. That is a story for another time. Since then Paul Sleeman has built a very limited number of large-capacity V-twin motorcycles carrying a 1920cc S&S engine. That is a story for another time.

Two prototypes. 1979 V1000 and 2005 V1200 Vulcan at Eason Neston, Towcester 2005. Photograph supplied by David Sharp.

2005, V1200 prototype – if only …. Photograph supplied by David Sharp.

Hesketh Owners Club meet at Easton Neston Hesketh works 2005. Mick Broom is next to black V1000 WKL982X. Photograph supplied by David Sharp.

Hesketh Owner’s Club meeting. Obviously these motorcycles have remained popular with owners. Photograph supplied by Mick Broom.

This Hesketh was photographed in Victoria in the eighties by Bob Fursdon. Word has it this machine is still ridden regularly in the Central Coast, NSW.

Special Thanks to Mick Broom and David Sharp for their assistance with this piece. Also Bob Fursdon who piqued my interest in Hesketh all over again when he showed me the above photograph.

Post script (below), this is the latest incarnation of Hesketh. The motorcycle, powered by a 1920cc S&S engine, has been produced by Paul Sleeman in the UK. Dubbed the ’24,’ Sleeman intends on producing only 24 of these machines as homage to the late James Hunt. 24 was Hunt’s number with the Hesketh Formula 1 Racing Team. At this time, only a handful of machines have been produced.