by Dan Talbot | Feb 7, 2023 | Uncategorized

Tales from the Shed: going down a VB rabbit hole

When we left last month, I had the Vincent dismantled and was feeling quite pleased with myself. If you recall I was washing a few profanities away with a couple of frosty cans of Victoria Bitter.

In my communique I also touched upon the second industrial revolution whilst heading down an internal combustion rabbit hole. Speaking of VB, rabbits and the industrial revolution, it’s timely we paid homage to the Louis Pasteur and his contribution the manufacture of Australian beers. As it turns out, Pasteur was responsible for allowing Australia’s largest brewery to export beer to the world thus the entire population could share in the aroma of subtle fruitiness complimented by sweet maltiness with a slight bitterness to finish (someone out there has just spat a mouthful of Corona over their screen).

So, what has all this got to do with classic British motorcycles? Nothing really, it’s just quite interesting.

Rabbits arrived in this country with the first fleet in 1788 but it wasn’t until 1859 that they became a problem. According to history, a British-born farmer, who wasn’t fond of the Australian fauna released two dozen rabbits, dozens of partridges and a half a dozen hares onto his land in Geelong, Victoria. By 1887 the rabbits hard spread out of control, North to Queensland and West to South Australia, prompting the NSW government to offer a reward of some £25,000 (or, $10M todays’ money) to anyone who could eradicate rabbits from Australia.

Apparently, Louis had been ill and was in need of a few francs so his wife suggested they have a crack at the prize. Louis reckoned he had just the thing, a virulent virus that would wipe out every rabbit on our island continent, but he was both too ill and too busy with things back in Paris so he sent his protégé, nephew Adrien Loir. Their intention was to use chicken cholera bacillus as the infectious agent to kill the rabbits. That’s right, they planned to eradicate rabbits with bird-flu.

Upon arrival in NSW, Dr Loir up the Australian Pasteur Institute on Rodd Island on the Paramatta River in Sydney. The experimentation was carried out under the watchful eyes of the judging committee and was expected to run for twelve months. This came as a bit of a surprise to Dr Loir who only had enough funds for he and his wife to spend a few weeks in Australia so he had to do some urgent fundraising.

Down in Victoria, emerging brewers at Carlsberg Brewery were experimenting with fermentation and sterilisation. One can imagine their excitement when they learned the father of microbiology was establishing an institute in Australia. Dr Loir was invited to Victoria where he was paid handsomely to teach the Australian brewers how to improve their product – right now some readers will be arguing the product has not advanced since 1887. Aside from refining the fermentation process, Dr Loir also taught the brewers advanced sterilisation processes which enabled the beer to be exported to the world in glass bottles.

As it turned out, Pasteur and Loir’s answer to the rabbit problem would not be released. It was thought the disease may harm the domestic avian population. Their idea also came up against opposition by wire manufactures who asserted they could stop the spread of the rodents with their rabbit-proof fences. The NSW government went with that idea but the reward was never paid out as it proved ineffective.

So there you have it, the machinery of the Busted Knuckle Garage is lubricated by the fruits of French scientists Professor Louis Pasteur and Dr Andrien Loir.

Now, back to work, that Vincent is not going to put itself together.

Cheers

by Dan Talbot | Feb 1, 2023 | Uncategorized

Tales from the Shed: let down by a ten-cent seal

This piece has been written by me for inclusion in Classic Vibrations, the magazine of the Indian Harley Club of Bunbury, Western Australia.

Newton’s third law states for every action in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction in force. Let’s look at that. A piston, for example, converts chemical energy to kinetic energy and through a series of mechanical interactions transfers that energy to the road where it propels the operator forward. For the kinetic energy to get to the road, there is a multitude of equal and opposite reactions that are mostly protesting and working against forward momentum. These mechanical devices, for the purposes of this communication let’s call them motorcycles, have reached incredible levels of sophistication and reliability yet some of us, in fact most folk reading this I suspect, have an unusual attraction to motorcycles from the last century.

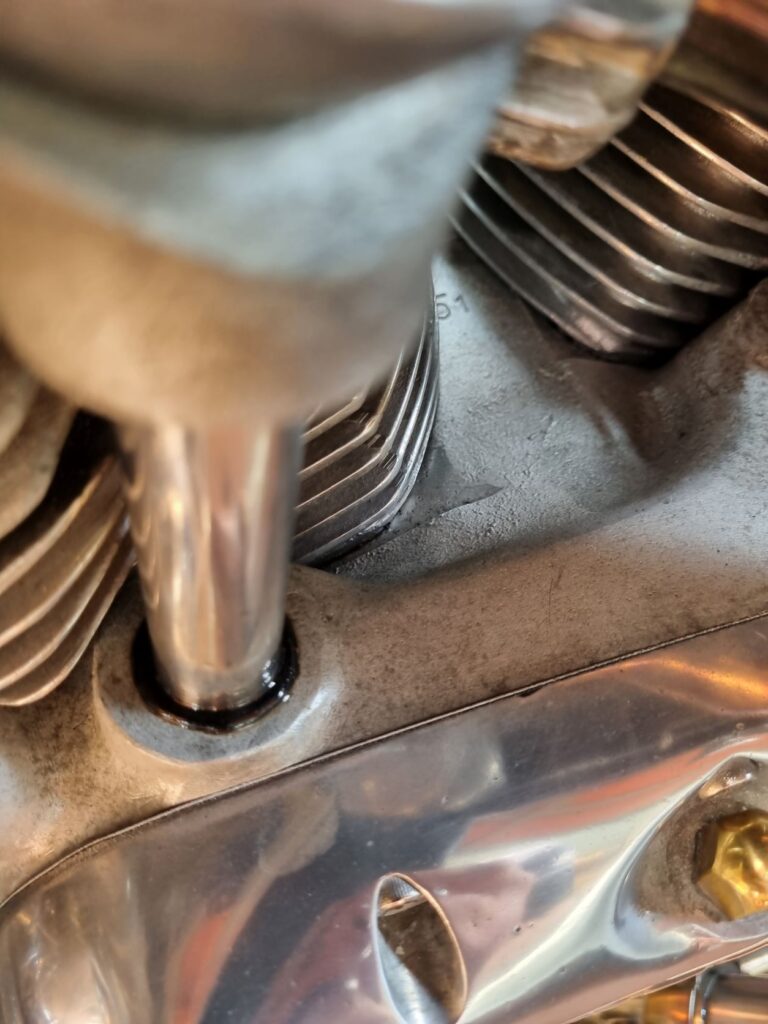

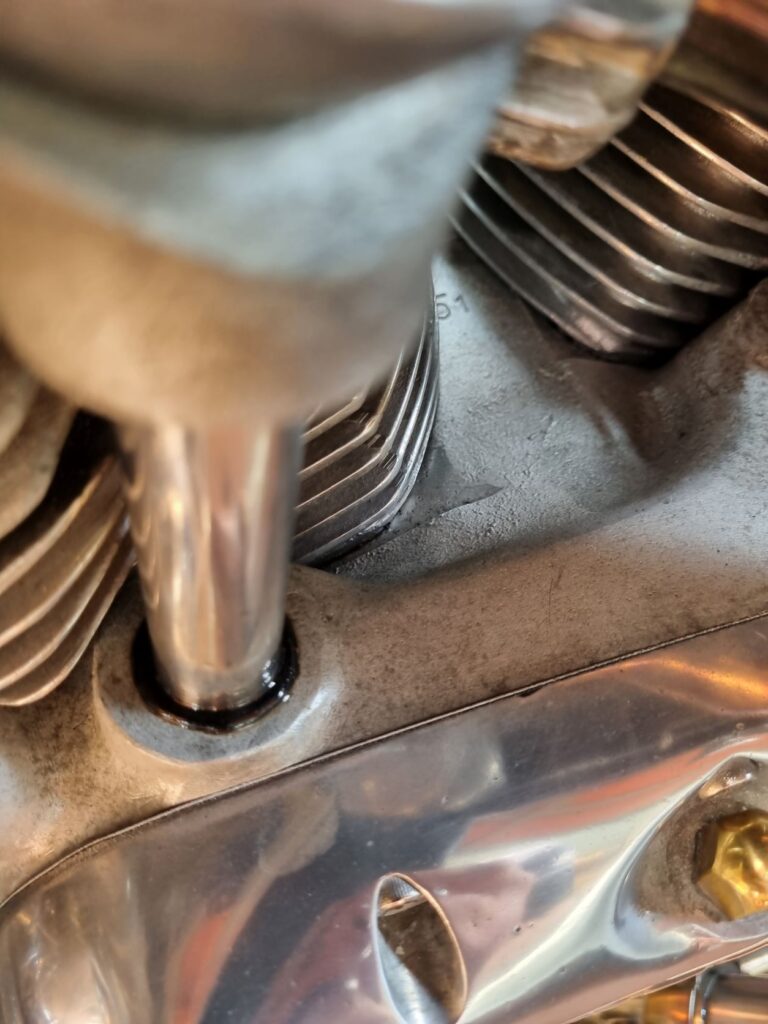

It looks innocuous enough, but this small trickle soon turned into an oily torrent.

We have a love for classical machinery that requires a deft ability on behalf of the operator to continue converting energy to forward propulsion in a variety of challenging conditions. For me, whilst I am cruising happily along on my classic motorcycle the world is a beautiful place. My machine is a valuable and prized example of the second industrial revolution. However, when that machine fails, it can quickly become a cantankerous and unreliable old bike. As happened recently.

I had been very much looking forward to the Australia Day run out of Boyanup. Being a combine event, I was equally looking forward to bringing my classic Mustang as well as my Vincent so some juggling of vehicles between home and Boyanup was required. Just to back-track slightly, on the Sunday before Australia Day I rode the Vincent to Mandurah to meet up with the Mob up there and joined them on a coffee run up into the hills. I have been aware for some time a pushrod seal on the Vincent were seeping oil and I have attempted makeshift repairs by wicking silicon into the aging seal and round the tube. But the equal and opposite forces could not be kept at bay and by the time we arrived at Dwellingup I was leaving embarrassing amounts of oil wherever I parked. I was 100 miles from home so both a clean-up and top-up were in order. Arriving home, I wicked more silicon into the offending seals in the hope I could stem the flow and make the Australia Day ride few days later. Alas, I couldn’t.

To get to the seal, the push rod tubes must be removed. To get to the push rod tubes the heads must be removed. To get to the heads the upper frame member must be removed ….

By the time I arrived in Boyanup on the Wednesday before Australia Day the Vincent had a coat of oil down the right side. Oil was migrating to the rear tyre so the machine was parked up and my Australia Day was thereafter confined to four-wheels. Sure, I have other bikes but my bottom lip was well and truly on the ground and I was not prepared to countenance another machine.

In the days following the ride, I licked my psychological wounds and retrieved the bike. The IHC Two Day Rally is fast approaching and I cannot ride the Vincent in the event in its current state so I had to get straight into it. I had contemplated handing the machine over to someone a little more skilled in Vincents than I but I was assured taking the heads of a Vinnie is no more difficult to those on my Triumphs or Ariels, so I dived in.

The offending seals are about the same size as a wedding ring. A ten-cent band of rubber that is easily popped out by the fingers once the pushrod tube is removed. The problem arises in removing the pushrod tubes for, to do that, the heads must be removed and, to do that, the front half of the frame must also be removed. It’s a massive job to get to four dinky little seals.

With the fuel tank off, the upper frame member is clearly visible. This needs to be removed, along with the front end to allow one to remove the heads.

I have mentioned a frame, but Vincents don’t have a frame in the normal sense of the motorcycle world. They have an upper frame member which bolts to the top of the engine and carries the girdraulic front forks, and a rear frame member which is basically a triangulated swingarm that holds the rear wheel and is bolted to the rear of the engine. The engine is essentially part of the frame: everything hangs off the engine.

This is it, a lot of work to get to the offending seal.

Things get a bit tricky removing the upper frame member because carburetors, electrics and cables all need to be removed or otherwise taken care of. Cleverly (or infuriatingly if one has to remove it) the upper frame member is also the oil tank so that has to be drained too. I must say, I found the dismantling the machine an enjoyable few hours in the shed. Sure, the neighbours heard the odd swear word but, by and large, things went quite smoothly. As the sun was dipping into the Indian Ocean just across the park, I rewarded myself with a couple of stubbies of Victoria Bitter. Sitting there, sipping one of Australia’s finest ales, I reflected on the beauty of the Vincent design.

The push rod tube. The top part is secured into the head by the gland nut, whereas the lower section simply pokes through the seal.

The synchronicity from the front wheel, through the engine to the rear of the machine almost punches you in the face (or perhaps that’s the VB). If we can go all Newtonian again, Phil Irving, the designer of the Vincent engine, knew exactly where the forces of mechanical design would work, and where they would fail. Now that I have the motorcycle apart, I can see his thesis laid out before me and it is brilliant. Let down in this case by a 10 cent rubber seal which bears a quite unequal relationship with the energy inherent in a 1000cc V-twin engine.

And now we wait for parts to arrive ex-East.

by Dan Talbot | May 9, 2022 | Collection, Events, Projects

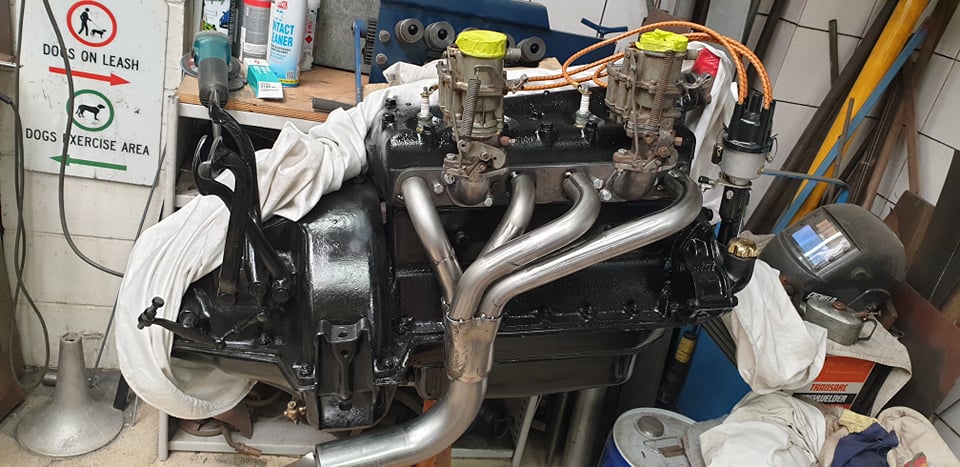

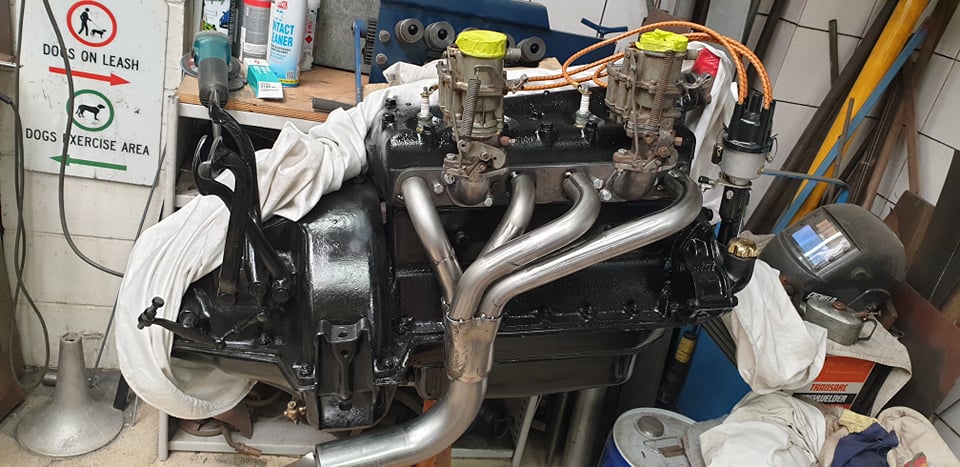

Things in Graeme’s shed have been developing rapidly since last we spoke: we have life. Sure, it was only a momentary wail in response to a Bendix slap on the buttocks, but just like a parent hearing the first cry of their child, it gladdened the heart of all those present.

The skeleton, with it’s beating heart, is ready for the body.

There was no cranking, and no extra priming of the twin Stromberg carburettors. The electronic fuel pump chattered for a few moments as it pressurised the system then, as soon as Graeme hit the starter, the engine instantaneously burst into life, surprising all those in the shed. That surprise was replaced by deep satisfaction as the 3-litre side-banger, four settled into a contented purr. Presently the exhaust is exiting the collector pipe without any hit of muffling. This is how the car will run at Perkolilli however the beautiful burble will be too much for road use.

Holden six nostalgia comes flooding back with these twin Stromberg carbs.

With no radiator, the experiment was brought to a close very early to avoid cooking the engine, but not before we captured a second burst on video for posterity purposes.

Of all the stages of a build, there is none as significant as a start-up. A major developmental signpost has been passed and the project can move to the next phase. In our case the body was reintroduced to the chassis. This can be achieved by two people, however, there were three of us and we got the body on without causing any scratches. It was at this point where the contrast between the black, heavy-metal chassis and the green of the tinware body, each perfectly complimenting the other.

The newly-painted body is wheeled into the work area ahead for being lifted back onto the chassis.

With the body permanently back in place (LOL), we set about test fitting other body items and within an hour the skeleton and its beating heart were transformed: a stunning green racing machine was revealed.

Recall, we touched on the tuned state of the engine in the last piece on Green T? The mods included an early veteran T high-compression head. Well, as Graeme says, you can’t always trust 100-year-old cylinder heads. A few days ago, whilst working on the engine, Graeme noticed an unusual mark on the side of the head. Instigation and a bit of digging revealed a large rust hole. The head was removed and replaced with a very special, and very rare Ward’s performance alloy racing head, cast in Perth by Allan Ward. Graeme has been saving this one for a special occasion. Evidently, its time has arrived. As Graeme says, “that should make this puppy really go.”

Ward high-performance alloy head created and cast in Western Australia.

Finally, before we leave this piece. For some years I have frequently mentioned Lake Perkolilli in the context of a motor racing circuit. I recently came across a passage written by WA Police Pioneer H.E. Graves, who, in 1929, came across the lake on one of his patrols out of Kalgoorlie. Graves describes Perkolilli as, “Surely one of the world’s smaller wonders. Imagine a country dense and chocked with that low, grey-green growth; bridle tracks worming through, an occasional lizard the only company. Out of all this the lake suddenly breaks. It is a huge, roughly circular area of clay. At its edge most unaccountably all vegetation sharply ends. The land becomes dead. The surface of the clay is utterly flat, glass-like, smooth like a mirror. Painfully it reflects the glare of the sun, so that the beholder blinks from its sheen. There must be salt or poison in the land to produce that shining sterility” (Graves, p. 117-118, 1937).

For a more contemporary description, we turn to the Gold Region Tourism Organisation, “Lake Perkolilli is a unique, rock hard claypan which has been the location for many Australian speed records. It was almost forgotten until vintage motor racing enthusiasts returned to bring it to life once again. Lake Perkolilli comes to life before dawn when the coffee p ots start boiling and the smell of frying bacon starts wafting across the camping areas. There is always someone who starts an unmuffled car or bike engine to break the silence. Aah, the music of motors to wake the late risers!”

The Red Dust Revival 2022 medallion has been cast and is proudly displayed on the dash of Green T.

by Dan Talbot | Apr 20, 2022 | Collection, Events, Projects

Out little race special is rapidly taking shape at the hand of master body-builder and engineer, Graeme Lockhart. In fact, it has actually taken shape – past tense. There will be no more cutting, welding, persuading or moulding of the body because it now has a lush coat on British Racing Green – again, by Graeme. Added to this, the chassis has also been treated to a protective coat of POR15.

The engine is back in the chassis and will remain so for now as that too is finished and, barring catastrophes, it will be a goer. Twin down-draft Stromberg carbs, increased compression and custom-made (ie Graeme-made) headers will see the one-hundred-year-old engine produce almost twice the original horsepower. Although, I should add stock was only ever 20 horsepower.

I’ll let Graeme describe what he’s done, “It has high compression pistons and is fitted with an early veteran T high compression head, up from 4:1 to probably 5.5:1. The engine now has 0.030 over-size bore and 12 kg off the flywheel. The crank, rods and pistons have been balanced. Ignition is by distributor and the camshaft is fitted with an aluminium timing gear – advanced 7 degrees. But, apart from that, it’s all stock.”

The heavy Model T flywheel has been relieved of some 12 kilograms.

As I said previously, the trick will be to use the extra power without breaking the crankshaft, the Achilles heal of any hot Model T engine. Then there is getting the power to the rear. The transmission has been rebuilt with new bushes and, where possible, modern materials that will add a touch of reliability, such as kevlar clutch bands. The flywheel has oil slingers added to force oil back to the front of the engine (recall these old engines didn’t have an oil pump, they were lubricated by the crank splashing through the oil in the sump). Graeme has added an external pipe to transport the captured oil forwards and thus aid in keeping the moving parts moving.

In this state, the Model T transmission looks much more modern than its 100-plus years.

The final drive has been rebuilt using a high-speed, racing crown-wheel and pinion that raises the final ratio to 3:1, instead of the standard 4.4:1. This sounds counterintuitive but essentially, the lower the number, the higher the ratio. With a higher ratio the engine turns less per revolution of the wheels and we go faster.

So, what does all this mean? In a nut-shell, this will be a period race car that goes as good as it looks.

The following montage will run from most recent to early stages of the build.

High compression pistons protrude into the combustion space and will add some much-needed horsepower to the ancient engine.

The first coat of the lush British Racing Green has been applied and looks amazing. It will almost be a shame to cover it in red dust!

The engine is back in the chassis and there it will stay, subject to continued good running.

Rear view.

These four massive slugs displace 3 litres.

Twin down-draft Stromberg carbs and hand-made headers are just a couple of mods that will add to the power output. A distributor has been fitted, negating the need for the old Ford trembler coils.

Early veteran high compression head.

Just to revise where we’ve come from.

Seats have been fabricated completely by Graeme.

An early graft of the body, prior to it being widened – twice.

by Dan Talbot | Mar 23, 2022 | Uncategorized

Back in October last year I helped out as a marshal at WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally hosted by the Indian Harley Club. I enjoyed my roll as Clerk of Course, not least because I got to spend a whole week touring the South West of Western Australia on my ’48 Vincent HRD – which is by no means a veteran motorcycle.

Subsequent to the event, my friend, and fellow IHC club member, Des Lewis released a very good quality video of the rally (WA Veteran Motorcycle Rally 2021 – YouTube). Such is Des’ prowess with the camera, at the end of his video, my wife turned to me and said “you should get one of those.” “Okay, challenge accepted.”

Veteran motorcycles rarely come up for sale and, when they do, they generally cost a few bob. An added complication is I have a particular hankering for a v-twin. The ones I have gravitated towards start at about $75k (AUD) and go up from there. It may surprise a few readers that I don’t have a lazy $100k waiting for the right veteran motorcycle to come available. I do however have the connections and ability to rebuild a project machine. A machine that will still start at about $20k for a v-twin. If I am going to get onto a veteran Excelsior, Yale or Pope, I will need a fairly decent starting wedge. I will need to sell something. I resolved to swing back to the Rocket 3 project (part 1 can be viewed here and part 2 here). That job has been parked up whilst I have been busy elsewhere. The fly in this ointment is: I am telling myself this is a rebuild that will be offered for sale.

Long before Triumph named their 2.3 litre behemoth the Rocket 3, almost 6,000 BSA’s Rocket 3 motorcycles had made their presence felt on the racetrack and in the boardroom. These bikes were manufactured from 1968 to 1972. Their Triumph stablemate, the Trident, lasted a little longer into the mid-seventies.

My once grand 1971 Rocket 3 came to me as basket case of forgotten dreams. A relic of its former self, certainly not something befitting the victory in the 1971 Daytona 200 or the machine that was able to conquer Agostini’s MV at Mallory Park in the same year. Two frames were thrown into the deal, from which I was be able to salvage one. The bike had clearly been crashed, big-time. Despite being an obvious write-off, the assembled parts arrived in Australia with a title and import approval. It had been uncovered by a friend who lived and worked in the US for about seven years. Like me, Steve has an unhealthy attachment to triple cylinder British bikes, namely, Triumph Tridents and BSA Rocket 3 cycles. Every time Steve saw a triple come on to US the market for under $2,000USD he would snap it up. During his seven years, Steve amassed some 14 motorcycles, two of which now reside in my shed (you will note I’m referring to the basket case Beeza as a motorcycle). Alarmingly, he still has a container full of bikes in West Virginia awaiting dispatch to Australia, some of which will no doubt end up my shed. Back to the pile of rubble.

During some cut and tuck between the donor frame and the crashed one, we had cause to cut the head stock from the frame. Only then, one can see how thick the metal tubing is. It’s massive. Looking again at the bent tubes and thinking about the forces that would be required to bend it are a little bit mind boggling. I doubt the person who crashed it would have survived. There was some serious impact there.

Two frames become one. Note the bends around the head stock. This frame should have been grey, instead, it had been repainted in a blue metallic finish. It also had the two down tubes replaced at some time, causing me to suspect it had been crashed twice.

The repaired frame has been resprayed in a lush black paint. I did consider powder coat but paint much closer resembles the original without the chunky, plastic-coating quality powder coat produces. Whilst the frame was in the paint shop, I turned my attention to the guards. The later Rocket 3 incarnation, starting in 1971, has acres of chrome, including the tank and guards. The chrome and bling came out of BSA Triumph recovering from a design misstep. Actually, history shows there were quite a few missed steps.

During the frame reconstruction, we had cause to cut the top tube. This is how thick in is!

The BSA and Trident 3-cyclinder, 750cc engine is almost identical. The engine was originally a Triumph design however, BSA had acquired ownership of Triumph a dozen or so years earlier and, whilst they were separate entities, operating out of separate premises, BSA decided they wanted a piece of the triple action. Prototype machines were being tested in 1965 and could have gone into production for the 1966 model year. Simple badge-engineering should have done it however, not content with sharing the design across the two brands, BSA insisted on making a triple of their own and this is where things get a little ridiculous. The Triumph triple cylinder engine was built in the BSA factory at Small Heath, it was, for all intents and purposes a BSA engine. In following naming conventions of the day, engines destined for Triumph were stamped with the prefix T150. BSA engines were stamped A75. That’s easy, no problem there, except to see the difference between the engine prefixes one almost needs to get down on the ground to read the stampings.

The engine that started it all: the Triumph T150 750cc triple. Designed by Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele. Photograph supplied by Leonard Johnson.

It was decided the BSA engine would need a distinctive look so the barrels on the BSA unit were canted forward by 13 degrees, which (kind of) dissociate them from Triumph. The right-side timing and gearbox outer cases were also altered to provide another individual touch to the BSA item. Think of designing something that is basically the same yet requires re-tooling, casting, machining etc and the simple act of making minor changes becomes a major undertaking. Luckily, the internals remained the same between the two engines, as did just about every other piece of the triple.

My BSA Rocket 3 engine prior to stripping. Although not immediately apparent, the barrels on this engine are canted 13 degrees forward (as opposed to the Triumph T150 engine). Subtle changes to the timing case are also evident, otherwise both engines are essentially the same.

With the engine (almost) uniquely styled to BSA, it became apparent the Triumph duplex frame would not support the forwarded slanting engine so the BSA would need a new frame too. Conveniently, Triumph would later use the same set up to allow inclusion of an electric start behind the barrels of their 1975 T160, which would become the last of the triple cylinder Triumphs.

The finished product would add two years to the release of both bikes and BSA Triumph missed the opportunity to unleash the first mass-produced, multi-cylinder superbike onto the world market. Instead of releasing their world-beating machine in 1966, it was released in 1968, mere weeks before Honda came along with their new 750/4. The Honda Four was almost as fast as the British triple but was less expensive and would prove to be more reliable than the BSA Triumph offering. The Brits had been caught resting upon their laurels. They were the motorcycle super-power of the time and probably expected to remain as such. As touched on earlier, Triumph and BSA triples went of to win production racing around the world, including the two most famous races of the time, the Isle of Man and Daytona. BSA dominated the American AMA competition well into the 70s but sales of the Japanese bikes sored, whilst sales of the British machines stagnated. Aside from the expense of the British machines, they had a distinctive style that did not go over well with the buying public.

To celebrate the release of the new machines BSA/Triumph engaged Ogle Design Company headed by David Ogle. Ogle Design were known for creating the Raleigh Chopper bicycle, toasters and an odd little three-wheel motor car by the Reliant Motor Company. In 1968 they entered the two-wheeled world when contracted by BSA/Triumph to put the finishing touches to their new triple cylinder motorcycles. It was a disaster. The famous lines of the Triumph twin, one of the most iconic motorcycles of all time, were lost. In its place was a slab-sided fuel tank, massive side covers and futuristic mufflers – referred to these days as ‘Rayguns.’

The Ogle Designed first incarnation of the BSA Rocket 3. Quirky at the time of release, these machines are now highly sort after.

Note the ‘Raygun’ exhaust. Considered a bit odd at the time of release, there mufflers are now very much sort after. Photograph by Tim Hesford.

The new machine was a hit with road-testers and racers but it failed to win the hearts and minds of Triumph owners, and potential owners. Motorcycle journalist Bruce Main Smith described the Rocket 3 as: “Biggest and most beautiful hunk of reciprocating machinery ever built.” It would take two years before the Ogle hoodoo could be undone and BSA/Triumph returned to the tear-drop tank, high bars and megaphone style exhausts. The new machines were released in 1971, predominately to the US, gaining unofficial title as ‘Export’ models. It is this variant of the BSA Rocket 3 that I am bringing back to life.

By 1971, BSA Triumph began to offer an alternative version of their machines designed to appeal to US buyers. The machines were dubbed ‘export’ models. This motorcycle is owned by Warren Hodder in New Zealand. The photograph has been supplied by Warren Hodder.

Note the Dove Grey colour of the frame. This wasn’t received all that well and by the end of ’71 BSA had gone back to a black fame. Photograph by Warren Hodder.

As each gleaming piece returns home and is stored or, in a few cases, refitted to the bike, I become just a little more attached. It’s like getting a kitten. The attraction is based first at a cute, superficial level but grows each day until the kitten becomes a cat and is loved very much as part of the family. Similarly, the BSA is starting to edge its way into my heart. It is going to be a special motorcycle and, as such, I throw only the best quality parts at it, such as forged steel conrods and chrome-plating that seemingly has no end. I could get cheaper, knock-off items from India but I want to retain the original items, even if it is more costly (just in case I end up keeping the bike).

Paying for the re-plating of a motorcycle that was lavished in chromium is arduous. I send parts to the platers piecemeal, so as not to shock the wife with too large a debit in our bank account. The guards cost $500 to replate. It sounds like a lot of money but the finished product is magnificent. The new chrome guard tucked in the black frame looks splendid. The next instalment of pieces for the chrome-plater are on their way.

Also on their way to the platers are all the fasteners and ancillary pieces that I had previously re-finished in zinc. This was a mistake. As the project has been parked up for a couple of years the zinc has discoloured and cannot be put back on the bike in the present state. I will now have them re-plated in cadmium (like I should have done in the first place).

This lot are going back to the electroplaters to be redone in cadmium. Which I should have done in the first instance.

On a final note, and going back to chrome, the Export model fuel tank was chromed and painted – not unlike the Ariel I have just finished and reported on in last month’s Classic Vibrations. Organising a union of chrome and paint is difficult in WA. Platers charge enormous amounts and they can take months to be finished. For some years, whenever I’ve needed chrome and paint, I visit John Berkshire, the former owner of Vintage and Modern Motorcycles. Vintage and Modern had a premises in the same block of units as K & D Metal Finishers and John has maintained his connection with Kerry from K & D. The result being, I have a one-stop service that turns out first-class paint and chrome products. To this end, I now have a beautiful orange and chrome tank waiting to go back onto the motorcycle.

The second lot of chrome has been completed. The first being the fuel tank, the third lot was the guards and the fourth is about to be sent off to the electroplater.

The fourth, and hopefully final, lot of parts are off to be re-plated. In most cases these items could be obtained as reproduced pieces out of India but I feel better using the original items – even if it does cost a bit more.

Fresh chrome on lush, black paint.

Special thanks to Tim Hesford, Warren Hodder and Leonard Johnson for supplying photographs of their motorcycles.