by Dan Talbot | Jun 25, 2023 | Projects, Racing

Over the past thirty years or so of involvement in classic motorcycles I have witnessed the evolution of the spare parts industry as it has gone through various stages to the point where we are now at, with everything we may need merely a click away. I suspect we’ve all had those experiences with the cursor hovering over something that’s far too expensive, one glass of Shiraz too many and ‘click’ it’s mine. Check billet alloy bonnet hinges on my Mustang.

In my experience you need not stop at alloy bonnet hinges, it is possible to build a whole 1966 Mustang, or a 1914 Model T car or a 1948 Vincent twin, entirely from after-market spare parts. Often those parts come from the UK or the US but more and more these days they are made in Taiwan and India.

“The bitterness of poor quality remains long after the sweetness of low price is forgotten” Benjamin Franklin would approve.

If you look at the Mustang just about every body panel you see, except the roof, are Dynacorn pressings out of Taiwan and Mexico. Towards the end of my Mustang restoration, I had a display plate made up that read ‘THESEUS.’ The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that asks if a ship, for example, has had all of its original planks changed during its lifetime is it still fundamentally the same ship? If not, at what point, what number plank, did it cease being the ship of Theseus?

For a time, in fact a long time, the Mustang was driven on a DoT permit bearing the plate THESEUS. This generated enough perplexity to ensure spending a small fortune on the actual DoT plate was not a good idea.

In terms of motorcycles, in 2007 the Vincent Owners Club constructed a complete replica Black Shadow from their parts catalogue. The machine was sold at auction the following year for 34,000GBP, a not an insubstantial amount in 2008 but few would quibble as the machine was made entirely from parts manufactured in the UK. Had those parts been sourced from the Indian subcontinent the machine might not have been so well received.

Spare parts for Ariel and BSA are plentiful and can be delivered from the other side of the world more quickly than the other side of Australia. Due to my leaning towards British motorcycles my path to spares usually begins with local suppliers then extends to the WA metro area before the East Coast of Australia then the UK. At any time during those searches, I can be presented with brand-new, reproduction items, usually out of India.

Reproduction parts are such a big thing these days they even have their own slang: repop. They are made all over the world and, according to some, geography and quality have a direct relationship. I recall, in the days before Ebay, a member of the MG Car Club in Perth wanted a chrome radiator surround. He was informed by a fellow club member that a firm in South Australia was reproducing these items, upon which he was heard to retort, “I will not have any Australian-made junk on my car.” He ordered the piece out of the UK, no doubt at great expense, only to read “Made in Australia” stamped beneath the chrome when he unpacked his newly purchased English radiator surround.

Indian reproduction parts tend to be a bit of a lucky dip. Online chat forums are crowded with arguments for and against the quality of Indian repop spares. I’m going out on a bit of a limb here, but I will wager a good many of the motorcycle spares being sold off in the UK are of Indian origin. For the record, I have had good luck with repop fuel tanks, leather saddles etc so I am usually in the ‘for’ camp.

This tank on the Square Four arrived in Australia chromed and painted for about $500. It is first class quality. The leather seat cover was also sourced from India but the colour had to be toned down with some darker die than shown here.

This brings us neatly to my current rebuild, the Pindan Special, a ’39 Ariel 500 that that I introduced last month.

The Ariel came with a sound fuel tank that had been painted in 1989 and was subsequently set aside, unused. The state of the tank under the paint was unknown but it looked decent, so I really wanted to keep the tank, rather than import a new one out of India. Both the Deluxe and Red Hunter versions of my machine had chromed and painted tanks. To chrome a fuel tank can cost upwards of $1,000 and one can be well into the job before it is even known if the tank can be salvaged. Add another $1,000 for paint and pinstripe and the tank suddenly becomes a very costly item. Further, this machine was never going to be concourse. It’s part Hunter, part Deluxe and part bitza. I also have to keep reminding myself the primary reason for the build is a red dust racer, a bike for tearing across the pindan.

Building a machine for an event that will come around every three or four years is an extravagance in itself, agonizing over decisions to chrome or not to chrome was largely redundant as I could have manufactured in India and landed in WA, painted and chromed, for around $500. That would have been the sensible thing to do but it would irk me every time I saw the original tank sitting on a shelf. In the end, I opted for all-over gloss black, harking back to the VB origins of the machine.

So, to cut to the chase, the tank is back home resplendent in glossy, gloss black with a gold pinstripe – just like half the other machines in my shed. Thanks to Joe at Panelworx in Bunbury, the tank really does look amazing. With the dash panel being finished in chrome, the machine has just the right amount of lustre.

The original tank, dash panel fuel cap and trouble light switch are reunited temporarily before being tucked away to a safe place.

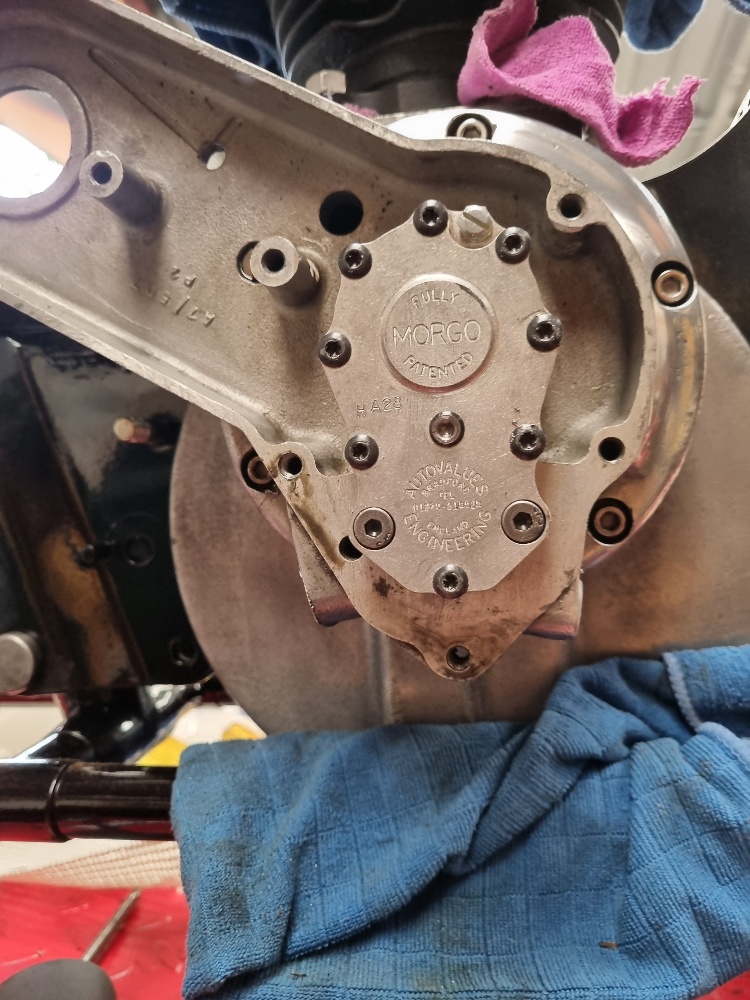

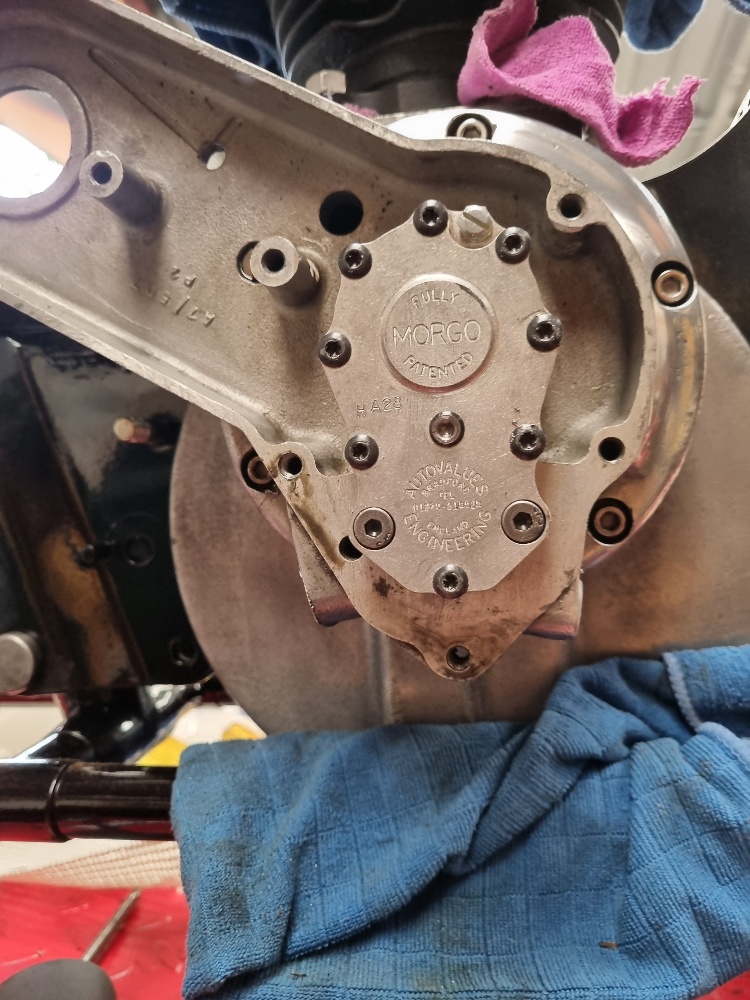

Elsewhere on the bike, I’ve recently fitted a Morgo rotary oil pump. I know this irks some folk who will insist the standard pump, designed about 100 years ago, is entirely sufficient but they are mostly puttering around the UK at 35 mph. I will have my machine pegged to the stop in the Australian desert so she will need all the help it can get and pushing oil through the engine (and the filter I’ve fitted) at twice the original rate is a no-brainer. What does irk me, is that I had to nibble quite a bit of alloy from the internal surfaces of the timing cover where it was fouling on the larger, rotary pump.

Morgo? Certainly more oil going through an engine that will be working very hard.

Newby belt drives and clutches are a work of art. This is one I put on the little Norton a couple of years ago.

Another thing that irks the purists are belt drives. I have secured a Newby belt drive and clutch set up. It is the fourth Newby belt drive that I have purchased and whilst they are quite expensive, they are a work of art. Added to this, the reliability of the belt, the smoothness, the outstanding Newby clutch and, most importantly, a lack of oil in the primary to leak out, are all good reason for choosing the Newby set up. Bob has only done a handful of Ariel conversions so I was flying by the seat of my parts and upon arrive, I soon learned the Newby clutch was too small for the spline on the gearbox main-shaft. I have removed the main-shaft and taken it to Brook Henry, of Vee Two fame, to have a spline cut on the shaft that will match the Newby clutch boss.

On a final note, things are held up a bit waiting on parts to arrive, mainly from the UK but also India.

This after-market oil filter will make a worthy addition to the Special and will provide me with some peace of mind.

I am waiting on bushes to finish this off. The supplier first sent me four, then one and, finally, the last three. Now all of need is to exchange my new stainless spindles.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 7, 2022 | Projects, Racing

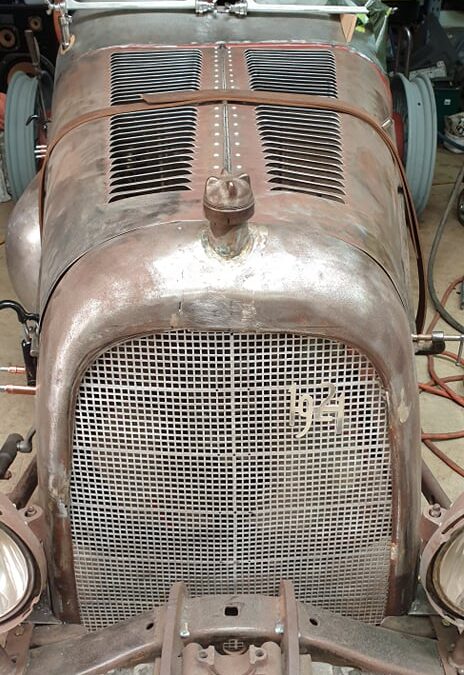

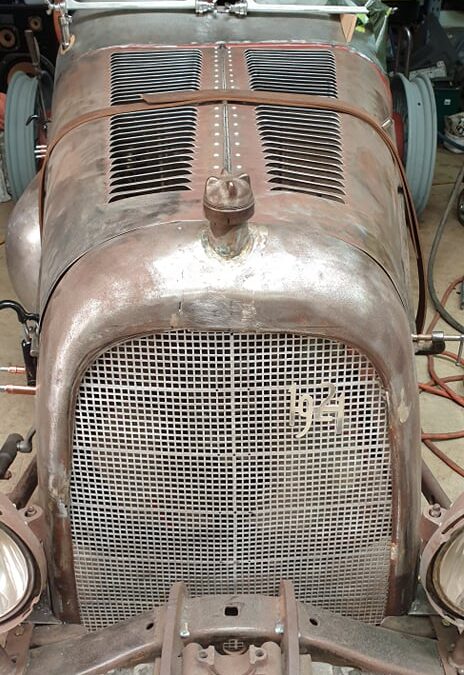

It’s over six months since we introduced Green T to the world. Standing in front of the car this week I couldn’t help but marvel at how Graeme has made the body wide enough for two grown humans whilst, at the same time, expressing an aerodynamic flow that was only beginning to evolve with the race cars of the twenties (that’s the nineteen-twenties by the way, 100 hundred years ago).

Recall Green T’s body first saw service on a 1922 or 1923 Aston Martin. The chassis on that car was numbered 1927, which is not the actual year of the car. It’s believed to be one of only 11 ‘short-chassis, Aston Martin race cars, which naturally makes it an extremely valuable piece of world motor racing history. That said, the car is believed to have had some four bodies during its lifetime in Australia, the one used by Graeme being removed when it was brought to WA in the early eighties. The original body would have been aluminium and the car has since been returned to such. The steel body, that was removed from the car continues to be molded by Graeme as he grafts it to the 1921 Ford Model T chassis. Graeme has shaped the metal according to his own design, aided along the way with lengths of plastic conduit, cardboard and a healthy dash of creativity.

The bonnet is so long a straight eight could go in there.

Quietly sitting in a corner of Graeme’s shed, the engine sits waiting to be introduced to the chassis. Graeme estimates the rebuilt Canadian four-banger, with its twin Stromberg carbs, extractors and high-performance head, will be pumping out twice the original allocation of horses. It won’t exactly pin the ears back, but we’re quietly confident 130 km/h will not be out of the question. If that sounds slow, remember front brakes weren’t really a thing in the twenties, nor were seat belts or roll-bars so 70 or 80 miles per hour will be plenty-fast enough. Furthermore, we’ll be racing on the slick red dust of Lake Perkolilli so top speed will likely be limited by my in-built sense of self preservation (and a wife punching me in the arm).

The ancient Ford Model T Four-banger has a new lease of life. Note the custom made exhaust system, distributor conversion, and twin Stromberg carbs.

With the body nearing completion, Graeme has begun preparation for the paint. I must say, one could almost seal the raw metal and present the car as she currently stands. The old sheet metal, free of paint and rust gleams like is was rolled just yesterday. In a nod to the famous 1921 Aston Martin GP car “Green Pea,” Green T will be finished in British Racing Green. One can’t imagine any other colour that would be remotely suitable. Not only does British Racing Green look stunning, it has linage in that it is the international motor racing colour of the United Kingdom and has been the livery of Lotus, Cooper, Jaguar and, of course, Aston Martin. It is the Aston Martin hue we are going for.

1921 marked Aston Martin’s entry onto the World Grand Prix circuit with a 1500cc, supercharged, all alloy engine that was lithe and powerful – for the era. Green T, on the other hand, has twice the cubes with a 3 litre, normally aspirated, cast iron engine. In typical American fashion, it pits size and muscle against technical sophistication, and comes off second best. I will, however, challenge any casual observers to pick the multi-million-dollar car from the one created in a shed in Western Australia. Such is the finish of Green T, it looks every bit the racing car it pays homage to.

This early picture of the project shows just how far Green T has come since Graeme first grafted the body onto the Model T chassis.

I would love to fit a supercharger to Green T but, the truth is, such a device would likely snap the crankshaft, which is already the Achille’s heal of warmed up Model T engines. I suggested to Graeme I should perhaps invest in an aftermarket, forged steel, Scat crankshaft. I had a bit of cash hidden away for a rainy day but then it rained cats and dogs. My newly purchased kitten fell ill and consumed the greater part of my rainy-day fund. Any upgraded crank will have to wait until we break this one! Challenge accepted.

Introducing the Aston Martin body to the Ford Model T chassis. Note how incredibly narrow the driver’s compartment is.

This was Graeme’s first go at making the body wider.

Attempt number two, and there we have it, a car wide enough to fit two grown-ups. Subsequent to taking this photograph Graeme has gone to considerable lengths to lift the plenum and shape the mid-section, whilst retaining and even improving upon of the sleek lines of the Aston.

by Dan Talbot | Mar 16, 2021 | Collection, Events, Racing

“Norton owners like nothing better than pulling their engines apart on Sunday afternoons (Donald Heather Man. Dir. AMC 1954-60).

With the greatest respect to Donald, some Norton owners actually prefer to be riding their machines, such as those who gathered in Donnybrook, Western Australia over the 13th and 14th of March, 2021. In excess of 40 Norton owners assembled for two days of riding, nattering about and admiring Norton motorcycles. Not just any Nortons mind you, this was a gathering of Norton motorcycles with only one cylinder. These folk think nothing better than riding their motorcycles on a Sunday afternoon however, given the last Norton single was manufactured in 1964, there’s plenty of afternoons spent pulling engines apart.

Donald Heather’s utterances were nothing more than motherhood statements designed to appease investors who, in 1960, were growing nervous with the lack of future direction the exhibited by the company. Rumours of unreliable and fallible machines were quelled by Heather as he fought to hang onto his lucrative position. The remedy proved to be a series of twin cylinder machines and, presumedly, the appointment of a more passionate and dedicated executive who would remain faithful to Norton’s heritage. However, by then, it was too little, too late. Norton twins were a fine machine but the company only managed to hang by its bootstraps. Gone was the racing heritage and successes that defined Norton’s early years.

1910 was Norton’s second year with his own engine. Only seven of these machines are known to exist in the world, here are two of the seven at the same event in Donnybrook, Western Australia.

Norton Motorcycles was established in 1898 by James Lansdowne Norton. Norton was a gifted engineer but a poor businessman and the company fell into receivership early in its life. This would signal the future for a manufacturer who was more concerned with performance and reliability than returning dividends for shareholders. Competing with the liquidity of Norton Motorcycles, was James Norton’s health. He fell ill as a young man and was left with a malady of premature aging, earning the young engineer the nick-name “Pa.”

Pa Norton was only 55 years of age when he passed away and sadly did not live long enough to witness the legacy of his creation – namely the most successful single cylinder motorcycle of all time. I can hear Ducati riders spitting their Chianti back into glasses everywhere. Whether, or not, Norton is the greatest motorcycle of all time is an argument best left for campfires, dining room tables and Christmas day punch-ups with the brother-in-law. What can’t be disputed is single cylinder Nortons are achingly beautiful motorcycles with performance to match. It’s no accident Norton dominated racing across the UK and Europe for the first half of the twentieth century. Ten Senior TT wins between 1920 and 1939 and 78 out of 92 Grand Prix races are impressive statistics in anyone’s language (including Italian).

In 1924 Pa Norton, suffering advanced cancer, was wheeled up to the main straight of the Isle of Man TT circuit to witness his motorcycles take out two TT trophies that year. Pa received the great chequered flag of life on 21 April 1925 and has been venerated ever since. By many people, including me. My trials and tribulations are well documented on this site and elsewhere, but, still I remain a faithful follower of the brand.

Muz and Rocket, two Norton enthusiasts the author is honoured to call friends.

This brings us neatly to the inaugural Norton Singles Run, hosted by the Indian Harley Club of Bunbury, Western Australia. The run, hatched by Norton enthusiasts Murray, Peter and Kelvin, was scheduled to take place in February was postponed when WA went into a Covid-enforced lock-down, throwing plans into disarray. Had it not been for the Covid factor one would expect many more motorcycles, however, by any measure, the inaugural event was a huge success. The line-up of machines on display was breathtaking. ‘Line-up’ is probably the wrong word, getting this mod to form anything resembling an orderly assembly simply for a photograph was not on the agenda. These blokes wanted to ride Nortons, talk Nortons and look at Nortons. Consider, there are seven 1910 Norton motorcycles know to currently exist in world. Two of them were present at the Norton Singles Run. 1910 was Pa’s second year of production with his own engines. Up until this time he had been using proprietary units from Swiz and French manufacturers. It was a Peugeot V-twin engine that powered Norton to victory in the first ever Isle of Man TT races in 1907. That was the last time Pa Norton would dabble in twins, as far as he was concerned future victories lie in the simplicity of singles. The rest is, as they say, history.

Another profile of the pair of 1910 Nortons. This one by Alan Wells.

One of the lovely ES2 Nortons that were in attendance at the inaugural Norton Singles Run in Donnybrook, Western Australia. Photograph by Alan Wells.

Another ES 2, this one from 1935. Pic by Alan Wells.

A line up of achingly beautiful Norton motorcycles. These ones are from 1924 to 1926.

Event organiser, Kelvin, wasn’t letting crutches prevent him participating in the ride.

Greg on his stunning ES2.

The 500cc 1910 Norton was getting along at a fair clip. Here she has just climbed a hill that would have a modern motorcycle looking for a lower gear – which is not an option for Andrew, he only has one.

The South West of Western Australia provided the ideal location to get about on vintage and veteran Norton motorcycles.

Manx silver, as far as the eye can see.

Saturday lunch stop was the Wild Bull Brewery in Ferguson Valley, Western Australia. A highly recommended venue.

Event organizer Murray on his 1929 CSI Norton 500, photograph by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography.

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

Norton Singles Run by Des Lewis of Mondo Photography

by Dan Talbot | Feb 11, 2019 | Events, Racing

The hill climb is one of the oldest forms of motorsport and it is making a comeback.

I was lucky enough to compete in two hill climbs during 2018. Designated vintage motorcycle hill climbs, the term ‘vintage’ simply means over 25 years old. Obviously, by 1993 motorcycles had reached epic proportions of speed and reliability and to term bikes as vintage merely because they are over 25 years is stretching the definition and unleashing a turbo-charged 1000 cc Kawasaki, for example, is probably not in the spirit of vintage hill climbs. Having said that, I’m happy to report just about every one of the 85 entrants at the Albany event was manufactured before 1980 with the majority from the fifties and sixties. Likewise the York Hill Climb.

York wasn’t my finest hour. The Triton was running super-rich and oiling up the left cylinder to the point at which it was fouling the plug (bearing in mind this is single carb engine). I managed to pull some half decent times which was mainly due to the short course but about halfway through the run my engine would begin to misfire. It didn’t lessen my fun or excitement but I felt the engine, in not running at is optimum, was an insult to my tuning skills – which are limited anyway. All I had to do was get the bike through the event because here was a fix at hand: in England.

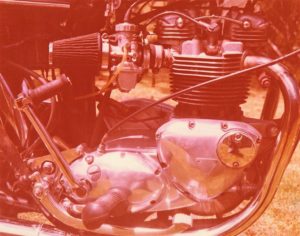

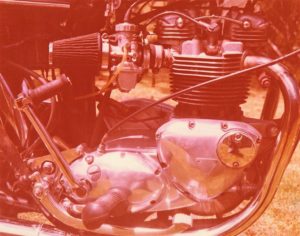

In June, whilst visiting the UK, my wife and I called in on the Morgo factory in Bradford where I picked up a new, big-bore 750cc barrel and pistons which would punch my Triton out by 100cc. I had purposefully kept my baggage to around 15 kilograms which would allow the weight of a full Morgo pistons and barrel kit. And two new Norton mufflers – but that’s another story. I didn’t need to go to the factory, I could have ordered the gear online but my bikes have so much Morgo gear tucked away their engines I kind of felt compelled to visit the place were the magic happens. I’m glad I did. My kit was packaged, waiting for me and the owner was touched that someone from Australia was visiting her business. Lynn, the owner of Morgo is the daughter of the late founder of the company and has been running things for the past four years since the passing of her father and by all accounts doing a fine job of things.

Morgo = more go! The 750 cc big-bore kit goes in, giving me 100 extra cc and Morgo bragging rights.

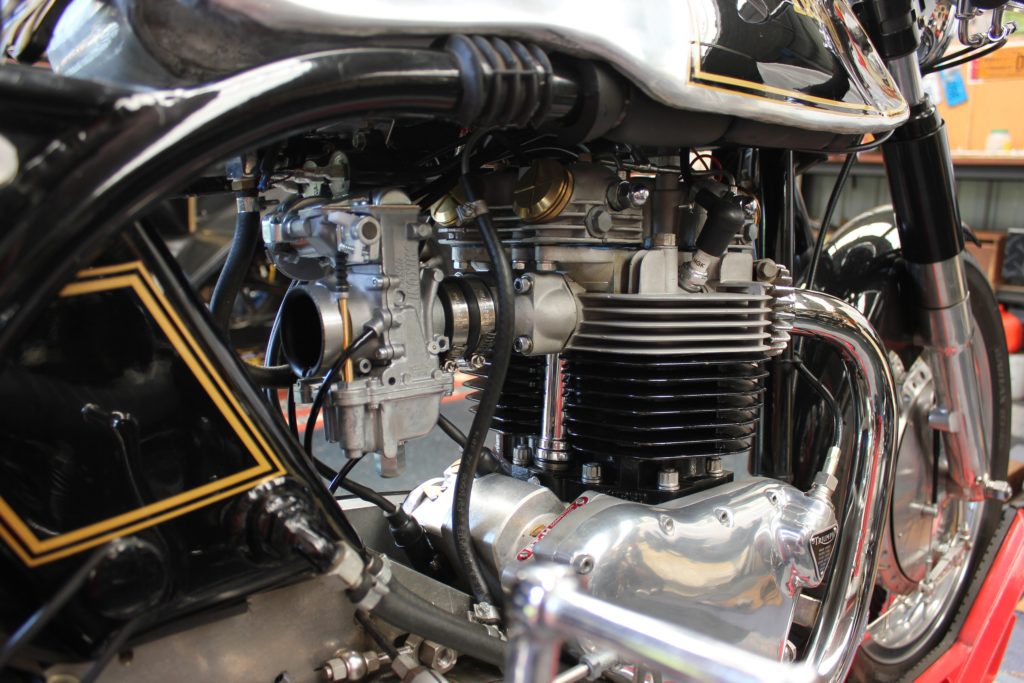

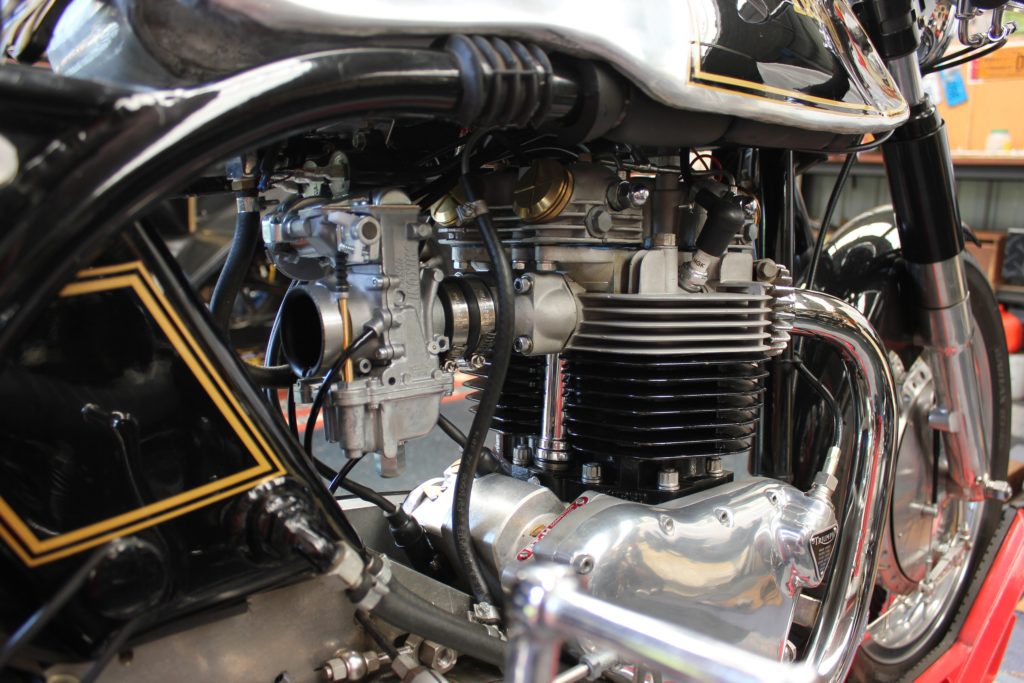

Extra cubes are all very well but they must be fed. Recall my comment above about not being all that well versed in motorcycle engine tuning? In rebuilding my Triton, I decided to retain the original single carb, 9-stud alloy head – as opposed to going to twin cards. To that end, I bought a new 36mm flat-side Mikuni carb from Mikuni Oz in Queensland. The Mikuni is a pumper style carb so it gives the engine an extra squirt of petrol when it’s most needed, i.e. when you crack the throttle.

Now there’s two types of people in classic motorcycle circles, Amal people and Mikuni people. I’m in the latter camp. The combination of the big-bore kit and the big pumper carb has my Triton running very sweetly so I’m willing to trade tiny bit English tradition for a big boost of Japanese performance.

My first big road bike was a 1977 Triumph Bonneville 750. The engine benefited enormously by fitting some larger, Mikuni carbs. Unfortunately the extra power was too much for the gearbox and I twisted the gearbox mainshaft in two. Twice.

I’ve yet to get the bike onto a dyno but for normal riding the Triton sounds and feels just like my first big road bike, a 1977 Bonneville which I bought new. In those days, incremental gains of one or two horsepower here and there seemed colossal in our never-ending search for more power and speed. It was like we were duty-bound to keep fettling the engine of our bikes to the point of blowing them up. After about two years of Bonneville ownership I fitted twin Mikuni carbs to the bike and had the inlet ports ground out to suit. The Bonny was transformed and for a brief time I enjoyed a healthy dose of horsepower – before I twisted and broke the gearbox main-shaft, twice. But I digress.

The Mikuni TM 36 pumper carb helps feed the 750 cc engine, bringing my Triton up to the same specs as the Bonneville I owned as a teenager. Mikuni Oz are in North Queensland and I recommend anyone struggling with tied, worn-out carbs to get in touch with Tom

By the time we got to Albany I figured I had the Triton well and truly sorted. Not so. The midrange was a bit flat but if I kept the reeves up high the engine hauled me up Mount Clarence in no short order. On my first run the bike almost cut out at the start line when it grabbed a great gulp of fuel and swallowed it whole. After a splutter, the engine took hold and launched me off the start line but it wasn’t enough to catch the Honda 750/4 that I was lined up against. I had much more success on the following three runs up against a Manx Norton. Before that however, I trundled off towards town and found a suburban hill, devoid of cars and shattered the Sunday morning peace whilst practising my hill starts half a dozen times. Satisfied I had perfected the art of the start, I returned to the hill climb to take on the Manx.

The legendary Manx is a highly-strung, highly geared, 500cc racing bike, not designed for drag racing up a hill but it’s oh so gorgeous and sounds sublime. I felt very privileged just to line up against a Manx so it was with some guilt that I beat it up the mountain on the three runs we shared. I felt even more guilty when the owner of the Manx sought me out specifically to offer to purchase my bike. I’ve had a few people offer to buy my Triton but I’ve yet to cave in to any offers and the Triton remains in the Motorshed garage.

My Triton shares its heritage with the Manx in the Featherbed frame made famous by Norton. Even the name is a contraction of Triumph and Norton. There is a story elsewhere on the Motorshed site as to how the Triton came into being which can be read here (https://motorshedcafe.com.au/the-triton/).

Alongside each other the bikes looked very similar. Naturally the Norton gives 250cc away to the Triumph engine in my bike but they both have a top speed of around 110 to 120 mph. The Norton gets there through a high state of tune and tall gearing, and that’s where I got the jump. The larger engine has more torque and therefore is able to get off the line quicker and climb better.

Both machines have an aggressive racing stance with a long reach to the clip-on handlebars and both were ridden by middle-age men who may not have been as flexible and subtle as we once were. Nevertheless, stretching out over the tank or a racing motorcycle allows a brief fantasy into the world of yesterday’s motorcycle racing champions, a feeling that is increased manyfold when we get to opportunity to actually race those bikes.

My practice starts revealed I could overcome the flat midrange by grabbing heaps of throttle at the start and riding the clutch to maintain the revs through first gear. Once in second gear with the throttle pegged, then again in third, the Triton came alive. When cranked into a sweeping righthand bend at full tilt, it never ceases to amaze me how Norton managed to design such a brilliant frame some 70 years ago. It feels rock solid and confidence-inspiring. In truth, the bike has much more to give but it would take a much better rider than me to explore limits of the Triton but, for now, I’m happy to make small gains in tunning, handling and, most importantly, riding ability.

The Triton and I, in our element. This photograph is by Andrew Haydock.

The perseverance, skinned knuckles and hours spent refining the bike over the past two years bore fruit on that day. At the top of the hill after each run I would join in with the other riders waiting to descend when the road was clear. Sitting up there, overlooking the bay with my engine clicking and clacking as it cooled, waiting for my adrenalin to return to normal levels, I was extremely happy with the performance of my ‘vintage’ motorcycle.

I reckon I’m ready to take it racing!

Photograph by John McKinnon.