by Dan Talbot | Jun 16, 2019 | Projects

Progress on the Norton has been a little slow of late due mainly to a few unforeseen events that, in the interests of doing a proper job, has resulted in items previously sent for repair having been retrieved. Confused? Don’t be, restorations typically have unforeseen and unknown challenges that test the mettle of the most ardent restorers.

It seems with the Norton I may have over-estimated the skills or our chosen spray painter because, as it turns out, the rear mudguard was simply too far gone. Arrangements were made to have the wonky, rusty and bent piece of 63 year old tin brought back to the shed for re-evaluation and I must say, I had to agree with Simon at Motorcycle Panel and Paint, she was in a poorly state. Fortunately, help was not far away.

Like the mudguard itself, the removable tail-piece was rusty, bent and buckled beyond repair.

Australia’s only manufacturer of motorcycle mudguards and fenders is located in Donnybrook, in the South West of Western Australia, not far from where we hail. Vintage Steel have a great website which is well worth a visit and, for international readers, they send product all over the world. Having collected the dodgy guard I wandered off to Vintage Steel and had a sit-down with Andrew and Michael. These guys love motorcycles and given the opportunity will yarn about bikes for hours. Surrounded by shiny, new, raw steel guards, some impressive metal-working machinery and a few crusty veteran motorcycles one quickly loses sense of time. A new guard was hatched in our collective musings and left with Andrew and Michael to turn into reality. The finished guard materialised within a few days and it’s a beauty.

The old, unrepairable rear mudguard in situ. Note the new item ready to be installed.

With the donor guard being so out of shape, Vintage Steel were unable to drill the mounting holes as the chances of them lining up with the frame would be remote. This required the frame having to be returned and mated to the guard. At this point, it should be pointed out, the craftsmen trusted with specialist paint and powder coat are some 250 kilometres away so logistics can be a bit of an ordeal, although not with the Norton. Whenever the word goes out to family and friends of the Busby Norton the items needing transport are delivered in a matter of hours. These people are well into the project.

The new mudguard is fitted into the frame and mounting holes drilled through the precious metal with deft precision

By the time it became apparent we needed the frame, work was well underway at S & S so there was a bit of a wait for the frame and 38 other pieces to be stripped, blasted, under-coated, top-coat applied and finished off with a clear coat. The result is sublime. Recall in Norton Part II how the frame was a mere representation of lugs and tubes, well dear readers, take a look at it now. My instruction to S & S Powder Coaters was, “finish it in glossy gloss black.” S & S have stepped up to the mark because it gleams. One can almost see one’s face in the shiny black tubes.

Measure twice, cut once.

With the frame back in the shed, it was time to begin drilling the mudguard. That’s right, drilling holes in the new, hand-crafted, rolled-metal mudguard. Many years ago, when my father was building his first aircraft, he had to be registered with the then Department of Civil Aviation who would come down and inspect the project has it progressed. They even inspected Dad’s shed before he commenced construction. In a nod to the DCA examiners, and to remind himself, Dad had a large banner along one wall of the shed that said “measure twice, cut once.” Sage advice that’s stayed with me for the past 40 or more years.

I measured, re-measured and measured once again before drilling tiny little holes in the Vintage guard. I mock-fitted the guard with little bolts and once I was satisfied everything was in the right place, I launched into drilling full-size holes through the mudguard mounting points. I’m happy to report measuring a bunch of times has meant the cuts are roughly in the right place and the guard will soon be sent back to Perth to be reunited with its sibling for panel and paint. Thanks to Vintage Steel there will be negligible panel and the guys at Motorcycle Panel and Paint can launch into coating the guard in glossy, gloss black paint.

Before we go, in our next discussion will visit the heart of the Norton – the engine. The engine has been pulled down and found to be in remarkably good condition. It seems, all that is required is a piston, rings and gasket set. An order has been put in with Feked Motorcycle Parts in the UK and, at the time of writing, I’m happy to report two parcels of Norton parts have just left Heathrow. The parcels include gaskets, wheel rims, spokes, rear shock absorbers, exhaust pipe and other assorted odds and ends. These are all new parts and generally of good quality, in most cases better than the original.

Finally, the head and rocker box have been vapour blasted by Rusty’s in Capel and they’ve come up beautiful and clean. We’ll talk about the engine in more detail soon, in the meantime, here’s a sneak preview.

Newly cleaned head and rocker box by Rusty’s in Capel.

by Dan Talbot | May 10, 2019 | Projects

There has been some major progress on the Norton this week. The frame has been repaired, likewise the oil tank and the whole lot has been bundled off to Perth for powder and paint.

For a time, during the formative years of the motorcycle, the gearbox and engine were two separate units within the frame of the machine. They were cast out of great lumps of alloy and filled with pieces of hardened steel that were stressed into a rotating mass that was a bee’s dick away from self-destructing. Most of the time. Sometimes that little bee’s dick wasn’t enough and the engine would fly apart, not this little M50 however, she’s a survivor.

The engine and gearbox were cobbled together by a chain that was referred to as the ‘primary-drive.’ The primary-drive chain spins the clutch housing which transfers power into the gearbox, through the various cogs then to the rear-drive sprocket and secondary-drive chain, to the rear wheel and finally, the road. Squeezing this complicated power-train into the frame, whilst maintaining functionality, required dedicated engineering and creativity. Norton was no exception, they were actually very successful in meeting their objectives of producing a motorcycle that was functional, nimble and reliable. The evidence of this can be found in the little 350 single that, some 63 years later, is still with us. Having said all this, the Norton is no less or no more complicated than its contemporaries from Triumph, BSA and a host of other manufactures that were meeting the demand for reliable, exciting and affordable motorcycles. I’m a little biased so I’m going to say Norton was more successful here than its rivals.

The engine from the M50, note the primary-drive sprocket at the side of the crank-case.

Combine hardware and tinwear prior to being sent off for paint and powder.

For the past couple of weeks I have been delving into the Pandora’s box of M50 parts, identifying what we have that will connect the engine and gearbox, what we will need, what needs to be repaired and what will go back into the machine as is. Working on this conglomeration of M50 hardware I have to consistently remind myself it is a 350 cc motorcycle. It is constructed in much the same way as my Triumph 650 twins. It’s hefty, solid and looks unbreakable. Sadly it’s not, but I digress.

Eventually, around the early sixties, someone thought to join the engine and gearbox in one unit and, in so doing, greatly simplified the design. The term ‘unit-construction’ was applied to this new form of motorcycle engineering and the bikes that went before were retrospectively called ‘pre-unit.’ Coming out of the factory in 1956 the Norton is well and truly in the pre-unit category of motorcycles. The bikes still had two drive chains, but the design enabled the bikes to be shorter, lighter and easier to manufacture.

Arranging an engine and gearbox in mid twentieth century motorcycle design required substantial hardware to keep everything in place. Admittedly, the bike develops less than 20 horsepower so one doesn’t expect the engine would exactly be bursting out of the frame, yet there are no less than six metal plates and eight bolts holding the engine and gearbox in place. For comparison purposes, my late-model Norton Commando has 90 horsepower and the engine is secured by four bolts. This perhaps suggests the little 350 might be a tad over-engineered but we have found a flaw.

One of the tubes on the side of the frame has a tiny crack in the paint. The frame is a substantial piece of kit so it’s hard to imagine it cracking, nevertheless, on grinding the paint away, the crack was proven to be more than a paint chip. It went down, well into the metal of the frame and required someone with better skills than I possess to repair it. Enter Rob Teale of Teale Custom https://www.facebook.com/tealecustom/ . To know Rob is to marvel at his skills in working metal, the man could build a Rolls Royce from a jam tin.

Metal has been ground away from the cracked frame in readiness for re-welding.

Like a dentist grinding away layers of tooth enamel, Rob was able to dig below the decay to clean metal and has repaired the frame with fresh welding. Likewise, the oil tank had to undergo a bit of the Teale magic and now both are as good as new, albeit a bright, shiny new that is exposed to the elements, inviting oxides to latch onto it like sugar to a tooth. To protect this raw metal, and all the other pieces that have been in a slow, elemental rot for some years, the whole lot has been packed off for a gleaming finish in glossy, gloss black (my terminology). Along with the frame, there’s an awful lot of pieces that make up this simple, small motorcycle that will be given a coat of powder and paint.

Rob has filled the broken frame tube with a fresh new weld.

Welded, ground back and ready for a new coat of glossy black powder.

Powder-coat has its limitations. It’s great for hardware and robust pieces that are likely to take bangs and knocks but it’s not all that suitable for tinware. Tinware includes the fuel tank, mudguards and any other items that are constructed from sheet metal that will be on show when the bike is back together. Tinware really needs to be painted, particularly when it’s been dented and requires filler. Powder over dents looks hideous and nothing grabs the eye more than a shiny dent. So, new maxim: hardware powder, tinware paint.

The oil tank cap was a bit rough and needed repairing.

Oil tank is done and ready for painting.

-

We love our Nortons at the Motor Shed. Here’s a picture of Dan at the Norton factory in 2018.

- .

Like Nortons?

Read more about our visit to the Norton factory at the Bike Shed Times.

Read more about our modern Norton Commando here

Read more about our Triton here.

.

by Dan Talbot | Apr 21, 2019 | Projects

A new project arrived in the shed this week in the form of a lovely little 1956 Norton 350 single. To be honest, the bike’s not so lovely – but she will be again soon.

This machine is a valuable heirloom that belongs to a local family who have been beset by health challenges in recent months. It was Chris’s intention to restore the motorcycle himself for his son but in recent times he has lost some dexterity which precludes tasks like motorcycle restoration so I am honoured to be charged with the responsibility for bringing this classic British single back to life.

Long before Nortons were tagged with such famous names as ‘Manx’ and ‘Commando,’ the company simply identified their motorcycles with a model designation. The 350 single is designated Model 50, of M50 for short. The M50 was introduced in 1933 and remained in production up until WWII when the factory moved away from civilian machines to concentrate on the war effort. Production resumed in 1956 which means this motorcycle belongs to first run of post-war M50 motorcycles.

Many folk, including me, think of Norton mainly in terms of competition motorcycles but the little M50 is more gentleman’s commuter than a racing bike. It’s smart, business-like and will be quite comfortable with gentle-on-the-back ergonomics. For decades Norton singles dominated motorcycle road racing in the UK and Europe so the M50 has a good pedigree. Motorcycle racing was James Lansdowne Norton’s passion. Affectionately known as “Pa” Norton, James was a talented and dedicated engineer who was at the forefront of engine design. Decades before Taglioni released his famous desmodromic valve system, Norton experimented with continual valve actuation which he named desmodromique. Before we go too far down this rabbit hole, it is mentioned here to demonstrate Norton were ahead of the game in the early days of motorcycle engineering, which, we hope, benefited the M50.

Tall for a 350 cc engine, the 1956 M50 is close to the end of the run for Norton singles which enjoyed many decades of success in racing and on the road.

The bike is finished in traditional Norton silver paintwork with chrome highlights and contrasting black frame. It is the archetypical British single but it’s got “Norton” written on the tank and that alone adds kudos. Manx silver lifts it to another level for this colour has been synonymous with Norton since the time they stamped their seal on the Isle of Man circuit in 1907. Silver, on black, on chrome and polished alloy, this motorcycle is going to look very smart indeed.

Having established the M50 looks sharp, comes with good manners and has a racing heritage, it’s perhaps time to take a step back and look at what we’ve got. Most people would see only a pile of dirty, rusty metal, faded alloy and perished rubber but we see a sound base from which to reconstruct a motorcycle. These days, Metal can be painted, polished or plated to a standard that is equal to, or better than, the original. And that’s just what is going to happen here.

Stepping back to look at what we’ve got, it appears we have everything needed to reconstruct a motorcycle.

Needs work!

In typical Motor Shed fashion, the motorcycle arrived in several large pieces (and lots of smaller ones). I don’t mind this, the machine will be dismantled to the last nut and bolt but basket cases inevitably have parts missing so it is somewhat of a lucky dip as to what’s there and what’s not. The package includes a spare engine that is partially dismantled and the original engine that matches the frame number.

The value of a good inspection. Having removed some paint this crack in the frame was revealed and will need to be repaired. This could have been dangerous once out on the road had it not been discovered.

The engine is a tall, substantial piece of alloy and steel. It’s hard to believe it’s only 350 cc but I have measured the bore and stroke and found it to be accurate. With some good vapour blasting and replating of all the fasteners, the engine is going to be an impressive sight, either on the bench or nestled into the contrasting black frame.

It must have been immensely satisfying to produce a motorcycle with your name on it. James Lansdowne Norton was justifiably proud to put his name to this motor and we will honour his work with fresh chrome plating on this valve cover to make it look as good as new.

The fuel tank was originally finished in a combination of paint and chrome. It would have been a time-consuming, and therefore expensive, process that helped Norton stand out from the crowd.

Speaking of the frame, it is a sturdy, solid piece of kit but has undergone a few repairs in its sixty-odd years of service. There are at least two welds that aren’t factory and soon there will be one more because I’ve discovered a large crack in one of the tubes. It’s an easy fix but will need someone with better welding skills than me. After that she will go in for a coat of lush black powder – which is sure to set a cat amongst the pigeons with the perennial argument of powder verses paint being ignited. I always err on the side of powder. It looks better, hides imperfections, is longer lasting and provides a better level of protections than paint. Sure, it’s not original but if a motorcycle is going to be ridden then powder is the best choice. If it’s going to be a museum piece then the more traditional coating of paint would be okay.

I’m sure Pa Norton would approve.

by Dan Talbot | Apr 14, 2019 | Events

Saturday April 13 and the second annual York Vintage Motorcycle Hill Climb is upon us. Unloading my bike and pushing it towards the pits, I’m feeling a nervous energy to be back at one of my favourite events on the Western Australia classic motorcycle calendar.

The event is staged on a public road that winds up Mount Brown, a short distance from the Wheatbelt town of York, Western Australia. The Mount Brown hillside is peppered with an assortment of beautiful classic motorcycles and not so beautiful old friends. Our bike banter is interrupted when someone fires up a British single, bellowing through a custom-made megaphone and, before long, the sweet fragrance of Castrol R descends on the mountain and I’m in heaven.

At the rider’s briefing the organisers reminded us several times this is not a race, it’s a regularity event – tell that to my right hand whilst I’m sitting on the starting line, blipping the throttle on my Triton, one eye on the flag, one on the opposition (aka fellow regularity event competitor).

The flag drops and I feed my newly installed BNR clutch to 750 cc of Triumph twin bellowing to be unleashed. We’re away, my front wheel comes up and I list to the right briefly before straightening up and finding second gear. The bike is pegged to the stop again and I’m immediately aware how sweet the Triton is running. I have an extra 100 cc this year, courtesy of a Morgo big-bore kit, and a Mikuni pumper carburettor. Last year my bike started to misfire about half way up the hill, this year she just keeps pulling and pulling.

The first bend, a right-hander, is upon me and third gear still has a way to run, back off ever so slightly, line the corner up and nail it. The Norton frame sits rock steady on narrow tyres and rockets out of the bend. It’s about 200 metres to the next braking point and I hold her flat to the skyline. Wait, wait, brakes. Tip her into the last right hander and, as soon as we can see the road ahead, open her up again for one final, brief blast before the finish line.

In terms of regularity, over five runs I am within .2 of a second within my nominated time. It’s not enough to even come close to the eventual winner however, for that I would have to be within .02 of a second!

Rolling back down the hill after my last go at the hill, the Triton and I are still running, the day has been a huge success. The organisers are to be congratulated on another fabulous event, here’s the day in pictures.

Outwards, cool as a cucumber, inside nerves are churning.

Described by the photographer, Russell Platts, “Off to a flying start. That’s an angry face if ever you saw one.”

Joachim Keese’ lovely Norton Dominator performed well, earning him second place. Photograph by Tony Wong.

Lambretta rider Tony Wong was up against Sid Barton. Sid had the last laugh when he placed second against Tony’s third.

We’re big fans of the Ariel marque here at the Motor Shed. https://motorshedcafe.com.au/rebuilding-the-ariel-part-ii/

Nortons where in abundance.

Former WA Speedway solo champion Bob O’Leary still knows how to ride the wheels of a motorcycle. In this case a JAP single in a Norton Featherbed frame. A beautiful machine.

Another Ariel, this time with room for two.

It’s a real “run what you brung” day.

Start line. Note the chocks that are used to stop the motorcycles rolling backwards whilst waiting for the flag to drop.

Bike and rider still running. That’s a successful day.

by Dan Talbot | Mar 23, 2019 | Collection, Projects

Rebuilding the Ariel Part II

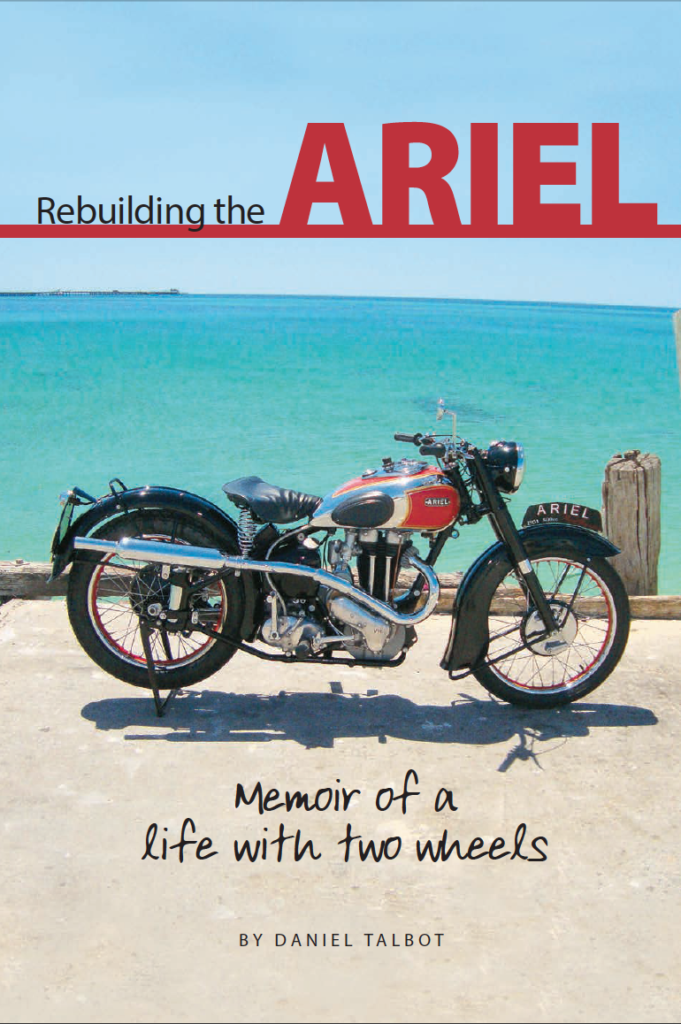

This is the second instalment from “Rebuilding the Ariel,” available on this site in eBook format.

Given this is only our second excerpt from Rebuilding the Ariel it is perhaps timely to have a brief discussion around the origins of the name Ariel. It’s no secret I love all things with two wheels, including bicycles, in fact, I have a particular fondness for the original bicycle: the penny farthing. There you go, it’s out there. I feel better having got that off my chest.

James Starley, the so-called ‘farther of the cycle industry,’ conceived the penny farthing and named it “Ariel,” after the character Ariel, the ‘spirit of the air,’ who was immortalised in Shakespeare’s sonnet “The Tempest.” In the Tempest, Ariel is a sprite who possess magical powers which, essentially, he uses for good. Ariel is powerful, agile and a loyal servant. It is easy to see how one may be inclined to name a motorcycle after such a character yet Starley chose this name some thirty years before the motorcycle came into existence.

Starley’s ungainly cycle, with its huge front wheel is neither powerful nor agile, however, one is indeed perched quite some way up in the air so perhaps that is what he had in mind. Starley’s hypothesis is as brilliant as it is simple. He found that by increasing the size of the driven wheel one could travel further with each turn of the legs. Naturally this simple form of mechanics was later made redundant through the advent of chain-driven gear system, another brilliant idea out of the Starley family, this time with the help of William Hillman, the founding father of the automobile that bears his name.

The new chain driven cycles were appropriately named the ‘safety bicycle’ as it put an end to riders toppling over the handlebars on out-of-control penny farthings, which were retrospectively named ‘ordinary bicycles,’ as opposed to the ‘unsafe,’ ‘dangerous,’ or ‘you must be crazy to ride this,’ bicycle.

Starley’s hypothesis is as brilliant as it is simple. He found that by increasing the size of the driven wheel one could travel further with each turn of the legs. Eventually, the wheel would grow too big for one to turn it. This is my old 55 inch wheel. I have now gone to a 58 inch Bolwell bicycle, which is a big wheel.

Starley passed away in 1881 leaving his sons to carry on the legacy of the Ariel although it was his nephew, John Kemp Starley, who also a member of the cycle production team that is credited with using Hillman’s idea to invent the chain-driven safety bicycle which was named the Rover, giving rise to the famous British motor vehicle company of the same name. Eventually the organisation became known as the Ariel Motorcycle Company with Ariel producing its first piston-powered machine in 1902, sadly after the death of Kemp Starley whose vision was firmly set on the motorcycle industry.

Shakespeare’s Ariel was said to be able to work up a storm, a tempest, sufficient enough to shipwreck the King of Naples and his crew. After providing loyal service to the magician Prospero, and having been freed from 12 years imprisonment at the behest of the witch Sycorax, Ariel is set free, hence, we have a loyal, powerful and free spirit giving its name to a motorcycle, presumedly with the same qualities. Now, back to our Ariel. We left off previously with me parking the bike up without having crashed it during my maiden voyage.

On reflection, I realise that Ariel was like nothing I had ridden ever before. Even before you start riding, the bike lets you know it’s different. The broad saddle, ‘tear-drop’ fuel tank with big rubber pads for the knees to prop against, bulbous front guard, an odd-looking instrument panel in the centre of the fuel tank are just some of the antiquities associated the motorcycle. Bakerlite switch-gear and an abundance of chrome-plating also let me know this machine was different from the modern machines I was familiar with.

When introduced to the Ariel I was still at the age where performance and looks counted for a lot in a motorcycle and, to me, the Ariel had neither. As I write this piece, almost three decades since that first trepid ride, and with lots of equally hair-raising and fun times spent on the Ariel, I now tend to think it is perhaps one of the most handsome machines ever made. Red paint upon chrome, gold pin-stripe and a black frame, add up to a visually stunning motorcycle. Take a look at the photographs and tell me you disagree (comments are welcome in the box below).

Back then, I loved dirt-bike racing and road-riding with equal measure, I still do, but in recent times I’ve returned to the more pure form of cycling – that which is without an engine. I trust these pages will attest to my twin passions of motorcycling and bicycling, for me, it matters not how much power is contained within my machine, if it’s on two-wheels I’m all for it.

Around the time I took my first excursion on the Red Hunter, I was quite heavily involved in bicycle racing and triathlon. I still love my cycle racing and can think of nothing better than to flog myself for six hours on a bicycle and, to do any good, we must train, which means I often spend more time riding bicycles than I do motorcycles.

Yep, we race bicycles – including these.

We race motorcycles too. If it’s got two wheels we’ll give it a go.

As I write this (wrote this), with the Ariel undergoing restoration (now finished), I wonder if it will see any more use than the half a dozen rides per year that the two other operational machines in my garage get to see. My friends jokingly comment I need a new battery every time I want to ride my modern Triumph. The older Triumph has a kick starter so a flat battery doesn’t prevent me from riding it. It makes little difference to me whether I ride my motorcycles or not, the important thing is they are there, ready to go, should the urge take me. I also like my bikes to be in top condition, even if they are dormant, and the Ariel has been in a rather poor condition for some time now. Postscript; there is now seven motorcycles in the shed and they still battle against my bicycles for time in the saddle.

Dad purchased the Ariel sight unseen out of Tasmania. As stated earlier, he bought it because he had one when he was a young fellow. The Red Hunter was one of the more desirable motorcycles of his era and about the time Dad turned 17 years of age he managed to secure a very nice example out of Bays’ Motorcycles in Perth. Evidently Dad’s father paid for his first Red Hunter so it’s fitting that I have managed to purloin this example from his grasp (more on that later).

By the time Dad acquired his first Ariel, the Red Hunter had been in production for about 20 years, having made a stunning debut at the Earls Court Motorcycle Show in 1931. The Red Hunter came in both 350 and 500cc variants and was known right from the start as a sports machine. That Ariel remained in production through two world wars, the Great Depression and some major company restructuring speaks volumes for the durability of the machinery produced by the company. In a further demonstration of durability, the official production run for the Red Hunter was 27 years, from 1932 to 1959.

Despite the Ariel being both a capable and desirable motorcycle, what Dad truly longed for was a Triumph Thunderbird. With its larger 650 cc twin cylinder engine, the Thunderbird was known as a true superbike of the era, capable of 100 miles per hour. As it turned out, he would have to wait another 40 odd years before the Thunderbird dream was to be realised.

In 2019, I’m happy to attest both the Ariel and the Thunderbird remain with me.

To be continued, or you can buy the book, in eBook or hardcopy format.