by Dan Talbot | Feb 19, 2019 | Collection

The Norton Commando emerges from the shed, liberated at last.

As a motorcycle journeyman I have, for most of my, life been chasing maximum power from my machines, I still vividly remember the first time I cracked 100 horsepower. It was the year 2000 and my new Triumph Sprint, which was in fact a 1999 model, produced 107 horses. It was unbelievably powerful and, had I not been so responsible (LOL), I could have wound up in all sorts of trouble on that bike with its top speed of 220 km/h. Some time later, in 2010, my Triumph 1050 Sprint produced a whopping 120 horsepower, and on it goes. So, it came as a surprise to me, and the great mirth to my motorcycle riding buddies, when I purchased my 2015 Norton Commando, and in the process, dropping back to 79 horsepower.

A stunning looking machine but not great out of the box.

So how can losing all that power be even remotely exciting I hear you ask. I must say, I asked myself the same question many times as I contemplated purchasing the Norton. At the end of the day sheer good looks and nostalgia won out but, as I sit here typing this, still feeling the buzz of 250 spirited kilometres on my Norton I can honestly say the way that bike delivers the goods is thoroughly exhilarating. Mind you, it hasn’t always been that good. In the 12 months I’ve owned by Norton, I’ve taken it from a choke-up, lack-lustre performance void to something akin to naked aggression, let me explain.

One of the most famous names in all motorcycledom.

When I finally hit the road on my Norton the engine had less than 100 kilometres on. It had, for about two years, been used for display purposes only. Firstly, in the dealership then in the first owner’s lounge-room and, as far as I can tell, was only ever started for amusement purposes. The first few rides I had left me with a kind of sinking dread. The bike surged and misfired at anything under 3,000 rpm and wasn’t so good above that range either. Put simply, it was horrible.

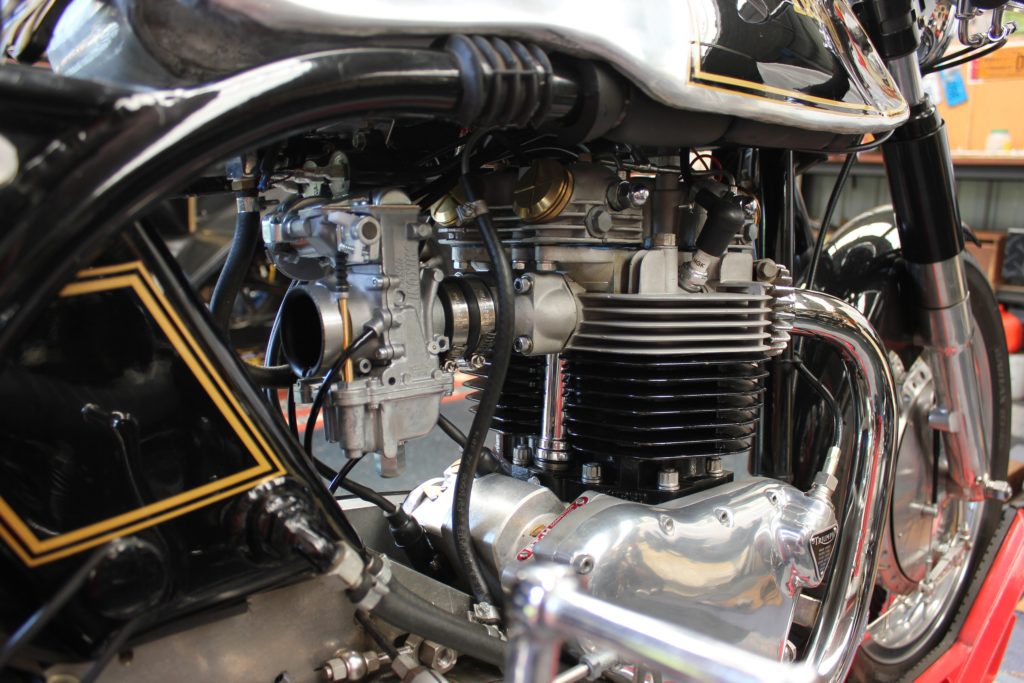

With no distributor on the West Coast, or, at that time, anywhere in Australia, I had to rely entirely upon my own skills to tune and fettle the engine. I turned to the only place one can in times like these – the internet. By modern-day standards the Norton is a fairly basic, push-rod, parallel twin cylinder engine. The major complication is fuel injection and the associated computer hardware and software. Even as I write this piece, with the bike running beautifully, I can’t help but pine for good-old carburettors.

The more I researched running problems associated with the new Norton twins the deeper the quagmire of responses grew. I managed to slough the fiction from the fact and quickly learned who knew what they were talking about, and who didn’t, in my favoured forums and sites for technical assistance. What I found early was the scourge of the European Emission Standards. Essentially, the Norton engine pretty much resembles that which rolled out of Birmingham in the form of the 500cc Norton Dominator in 1949, albeit with modern-day construction and materials. The Domi engine grew through various stages of 650, 750 and, finally, 850 cubic centimetres before the Commando was retired in 1977. Of course Norton and the famous Commando name has been revitalised in the modern machine I now own. How we got to this machine being re-released is a long story and one we shall revisit soon, but, for now, it is the modern incarnation we’re concerned with.

Even the name sounds cool to this long time devotee.

To get the bike through the Euro emissions Norton fit fuel injection and keep the smog to acceptable levels. Acceptable levels these days is generally where the air coming out of the exhaust is cleaner that that which goes into the engine! Remember this has a seventy-year heritage, it is like handing grandpa an iPhone. The get the grand old design to perform I replaced the coils, spark plug leads, spark plugs, cam position sensor and cleaned the fuel circuit of the detritus that was once petrol. I may have broken a few Euro standards but, heck, we’re not in Europe!

With each change the bike made incremental improvements, but nothing startling and nothing to help ease the knot in the pit of my stomach that was screaming out ‘what have you done?’

It became obvious I would eventually have to hand over my bike to someone versed in the twin arts of fuel system management and computer science. To me fuel circuit mapping is the proclivity of NASA boffins but unfortunately, it’s something we live with every time we start an engine that has been manufactured this century. We don’t have NASA in Australia, cripes, at that time we didn’t even have Norton in Australia. The only solution was for me to travel to Norton with my ECU in one hand credit card in the other. That’s Norton in the UK, a heck of a long way from Western Australia.

Donington Hall, hallowed ground nestled between Donington Castle and Donington race circuit.

We’ll see about that!

It was my intention to collect two sports mufflers from Norton and have the ECU mapped to suit, I wasn’t to be disappointed. Pretty soon after walking into Norton headquarters my bubble-wrapped mufflers were handed to me, ready to be stowed in my suitcase ahead of our flight home. The combine weight of the two sparkling new, stainless mufflers was less than 5 kg (which enable me to also pack a new barrel and pistons for one of my other bikes). My ECU was remapped whilst my wife and I sat in the waiting room with a Norton used in a recent James Bond movie as company.

Nortons are no longer assembled in dank, drafty sheds in Birmingham. The new facility is something akin to Downton Abby. Outside Donington Hall looks like a manor house, inside it is a modern, slick operation that reassures me the future of Norton is in good hands. Donington Hall is wedged on a parcel of land between Donington Racing Circuit and Castle Donington, a small town of about 6,000 inhabitants in Leicestershire, England. So plush is the facility, Norton CEO Stuart Garner actually lives there. Stuart’s Aston Martin, bearing the numberplate NOR7ON (sic), sits immediately outside his apartment. Until recently, Aussie Road Racing star Davo Johnson also lived there.

After collection my mufflers and newly flashed ECU, my wife and I went on a tour of the factory, whilst it was in full swing. Workers were pouring over partially assembled 961 twins – of which there were just three on the production line. The machines were exactly the same as mine yet I still felt a pang of envy of the new owners, such is the allure of the Norton.

In keeping with the original style of the Commando, the designers have reached a pleasing symmetry between engine and frame. The frame is slim and the engine tall which, essentially makes the bike feel large. At 6’ 3” the bike fits me perfectly and my feet are easily planted on the ground but shorter people might not feel so comfortable, however, any thoughts of comfort would likely be lost when the big twin is spun into life.

Talking of spinning, 270 degrees is the new black in engine layout. Triumph have been doing it for a while, the new Royal Enfield 650 will have it and Yamaha have known it for decades in their 850 parallel twins. Manufactures have come to understand the value in firing a twin at 270 and 450 degrees, emulating the characteristics of a Ducati L twin, namely a much smoother and more useful spread of power than the previous 360-degree firing order the British twins are known for, it just needs to be freed up, electronically in the ECU and physically in the exhaust. Fuel in, waste out, simple. Well eventually.

Back home and the stubby Norton sports mufflers are on. They take some getting used to but the sound is oh so sweet.

When I got home, I plugged my ECU back in, fitted the new mufflers and hit the starter. Bang, she’s alive, rorty and responsive. The ride was a revelation, a great improvement over previous sorties. The great lump of almost 1000 cc in a parallel twin is usable, sounds awesome and doesn’t shake me to pieces, not quite. The Norton has a balance shaft but it still vibrates and vibrations might not be everyone’s cup of Early Grey. If you love a silky-smooth, multi cylinder bike you’ll probably not enjoy the Norton. I like to know there’s a big engine propelling me forward and the Norton delivers that feeling in spades. I love it.

One thing I’m not so fond of is the five-speed gearbox. The box feels solid and changes with all the precision of a rifle bolt, but, out on the road in top gear, I find I’m frequently looking for another cog. It’s early days for me and the Norton but I do wonder, in this day and age where six speeds are the norm, why Norton has stuck with a five-speed transmission.

The new mufflers have been a very good investment. Combined with the re-mapped ECU, the engine now runs smooth and clean. The jerkiness of the overly lean ECU is gone, as is the strangled sound previously emitted from the large pea-shooter style, stock mufflers, although, if I have one criticism, I’m not sure why the pea-shooter could not be replicated in the sports muffler, instead of the stubby tubes the factory produces. That aside, the sound coming from those stubby tubes is sublime. On over-run the pipes emit a deep baritone burble and it sounds amazing, it’s enough to have me pegging the bike just to hear the bellow and growls the big twin makes, I know, I sound like a teenager.

All in all, I’m well pleased with the bike as it is now. It’s taken a bit to get it to this stage and one might well ask if it’s worth it when I could have purchased a new 1200 Bonneville and saved bucket loads of money. With each new ride the value of the machine is making itself felt. Recently I was out riding with some friends and I found I was pushing the Norton up into revs and speeds that I had previously stayed away from, as much for some perceived fragility as anything else, but the harder the bike is pushed the more she shines. After two days of spirited riding I tucked the Norton back in the shed with a self-satisfied grin that has been a long time in the making.

Yep, she may have little more than 80 horsepower but I reckon they must be Clydesdales!

With the Norton at last running fast and free I’m well pleased with the performance, albeit with a scant 80 horsepower. Check out that grin!

by Dan Talbot | Feb 13, 2019 | Collection, Projects

Those keen of eye may have noticed frequent references in various Motor Shed discourse about our ’56, 650 Triumph Thunderbird. The bike certainly comes in for a mention in Rebuilding the Ariel so we thought it was time to string some excerpts together from the book to keep the Triumph fans out there happy.

The star of Rebuilding the Ariel is, of course, an Ariel motorcycle. It is another one of my father’s former bikes purchased out of Tasmania in 1989 because Dad had one when he was 17 and felt like revisiting his youth again at the age of 55. Despite the Ariel being both a capable and desirable motorcycle during my father’s youth, what Dad truly longed for was a Triumph Thunderbird. With its larger 650 cc twin cylinder engine, the Thunderbird was known as a true superbike of the era, capable of 100 miles per hour.

This photograph was taken in 2010, after about 12 years ownership. The bike still scrubbed up okay but oil easily found its liberty and rust was forming on the barrels.

Dad finally managed to secure a Thunderbird a few years after the Ariel. It was a particularly nice example of a 1956 machine. The motorcycle is fitted with an English SU carburettor and finished in all-over silver, including the frame, which I was told indicates it was an export destined for Australia but I have since discovered that to be a myth. There are a few other myths about Thunderbirds that should be cleared up, or at least introduced here.

The original Thunderbird, if indeed there can be such a thing, was not a motorcycle, nor was it a Ford convertible, it was a creature from within the culture of the indigenous people of North America, a mythical giant bird that was able to cause the sound of thunder by flapping its wings together. It combined the freedom of being able to take to the air with power and grace, yet possessed supernatural powers that commanded respect and adoration.

Of course the name Thunderbird did not derive until after colonisation whereupon an English translation was put to the creature that was said to carry glowing snakes that were speared into the ground as lightning bolts. Adding to the mythology, the Thunderbird was said to be intelligent, wrathful and powerful, not to be trifled with and generally avoided at all costs.

The Triumph Thunderbird is none of these things, but, it is one very cool motorcycle.

My stepson is constantly amazed when we’re about and about on our bikes. People go out of their way to take a look at the Thunderbird and make all sorts of comments about how nice the bike is. Some recount stories of daring feats committed on Triumphs, whilst others ask if they may photograph the bike. At 19 years of age, James was slightly perplexed by all the attention the old bike gathered. He saw a motorcycle that was difficult to start, is not all that fast, doesn’t particularly corner well, has poor brakes and leaks oil.

She did, and still does, leak oil. Despite what was apparently a fine restoration, the Thunderbird regularly needed some tweaking to keep it in order, not the least of which was the odd dribble of oil. Anyone who has ever owned an old British bike, and a good many folk who haven’t, will testify to their capacity to spill their guts from orifices designed to contain lubricant rather than give it liberty. The Ariel was particularly bad for this. For the first decade of its time with us, the bike stayed in Dad’s shed on the farm. The occasional ride would coat the bike in dust thrown up by the long gravel driveway. Dust and oil are not good bed-fellows, they are in fact the enemy of concourse. Whenever I visited the farm I would usually get straight into some motorcycle maintenance, either with or without the Zen (long story – literally). Maintenance always started with a good degrease to get rid of all the oil and built up gravel dust.

The dirty bird.

Under the dust and grime lived a very nice example of Triumph’s flagship superbike for the fifties. The Thunderbird had been lovingly restored by a member of the Vintage Motorcycle Club in Perth. At the time the bike was restored I was in fact a member of that club but there was over 450 members so I was unable to place him. Sadly, the gentleman who restored the bike never got to fully enjoy it as he passed away soon after completing the restoration, receiving “the big chequered flag in the sky,” as the club used to so eloquently put it whenever they lost a member.

The bike was subsequently acquired by an ex-patriot Englishman who very soon thereafter decided he would migrate back to the Old Country. He loaded all his goods and chattels into a container and shipped it all back to the UK. He then gathered up his family and, similarly, shipped them all off ‘home.’ Evidently things didn’t go as well as expected. Upon arriving in England, the gentleman decided things weren’t that bad in Australia after-all and resolved to return. They actually left the UK before the container arrived, and returned to Perth. It took another two years before the container was turned around and arrived back in Western Australia, whereupon the Thunderbird was removed and promptly sold – to Dad.

I acquired the bike in 2009 when Dad’s hips and knees prevented him from starting and riding it. I rode the bike frequently for another eight years by which time it was starting to look a bit shabby and still leaked oil everywhere. I never did like the silver on silver so, in 2017 I resolved to give the machine a freshen up, a makeover if you like. Like many things that come into my garage, a simple makeover quickly turned into a full nut and bolt restoration.

More about that later, but here’s a sneak preview…

A silver tank and guards on a silver frame didn’t really agree with me so, in 2017, I pulled the bike down to freshen up the engine and re-do all the paint.

The strip-down begins.

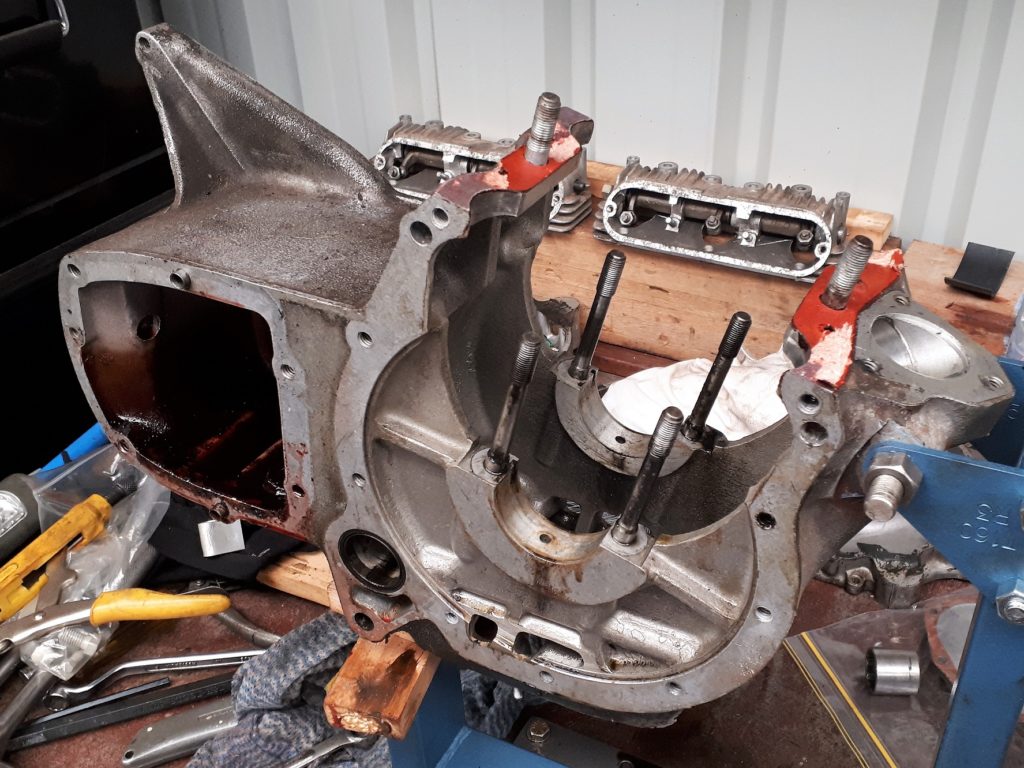

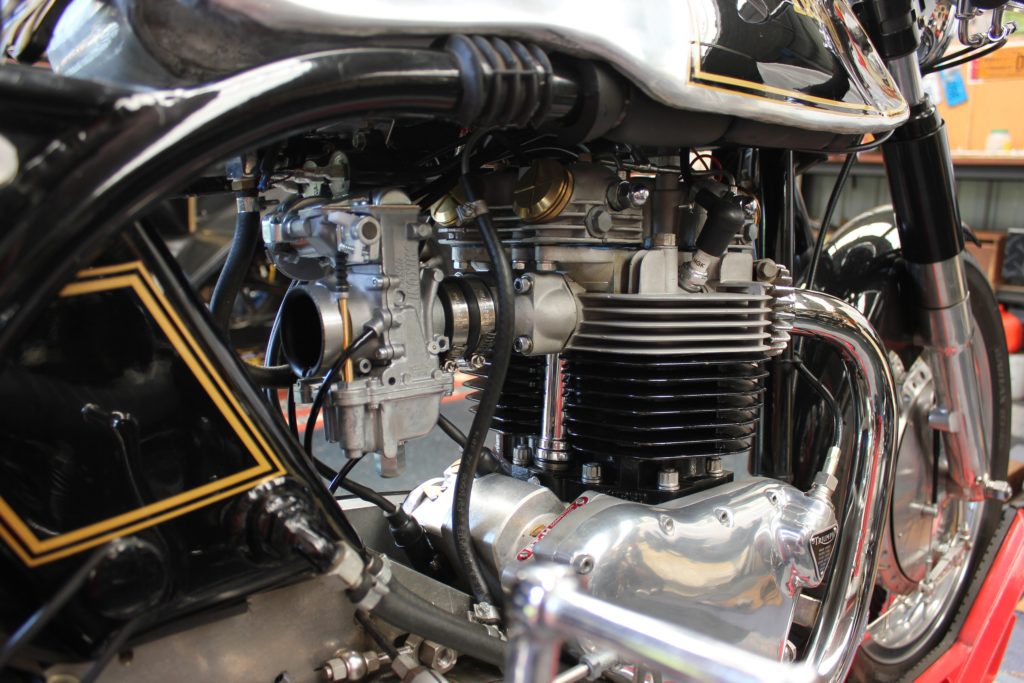

Triumph introduced their 500 cc twin cylinder engine to the world in 1937. In 1949 the Speed Twin engine was punched out to 650 cc and the Thunderbird was born. This is what my Thunderbird engine looked like when stripped to the last nut and bolt.

Parts ready to be sent for a coat of lush, gloss black paint.

This 650 cc parallel twin engine is such an icon it could almost be put on a plinth within the Guggenheim Museum.

The effort starts to pay off when the bike begins to be reassembled.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 12, 2019 | Projects

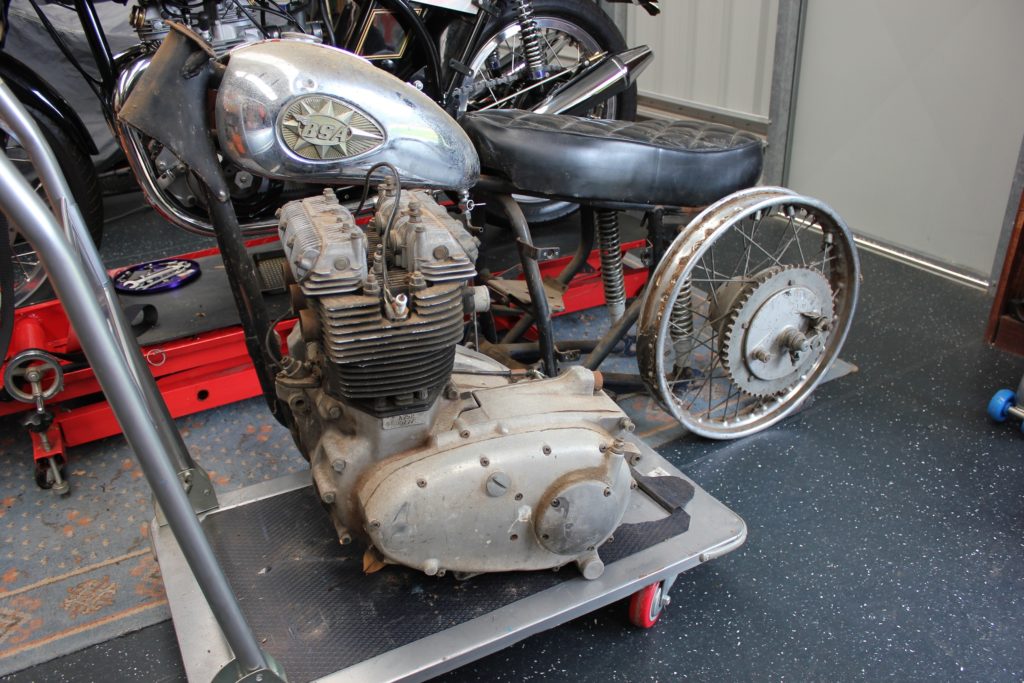

1971 BSA Rocket 3 Project

How the Rocket came to wind up in our shed has been discussed in the post Egli-trident-project-part-1 but, to recap, in searching for a donor engine to put into my Egli Trident project, I happened upon a veritable Aladdin’s Cave of classic Triumph and BSA triples. There were five Tridents and three BSA Rocket 3 motorcycles, in various states or repair, secreted away in the shed. All the bikes have been brought to Australia from the USA by the owner whilst he was working there over ten years ago.

Whenever Steve saw a classic triple pop up for sale under $USD2000 he bought it. Frequently he broke that rule, and now he has the afore-mentioned gaggle of bikes here in Australia and another container awaiting shipment in the US. Readers need not get too excited at this time, that second container has been sitting in Virginia for nigh on 10 years and it’s not about to leave a dock anytime soon. Steve is a man not to be hurried.

To date, I have secured one of the Rockets and we are now negotiating a Trident. Both of these bikes are matching numbers machines so I’m reluctant to separate the engines from either of them for my Egli project but I have a plan. More on that later, for now, we have a Rocket that needs some tender loving care.

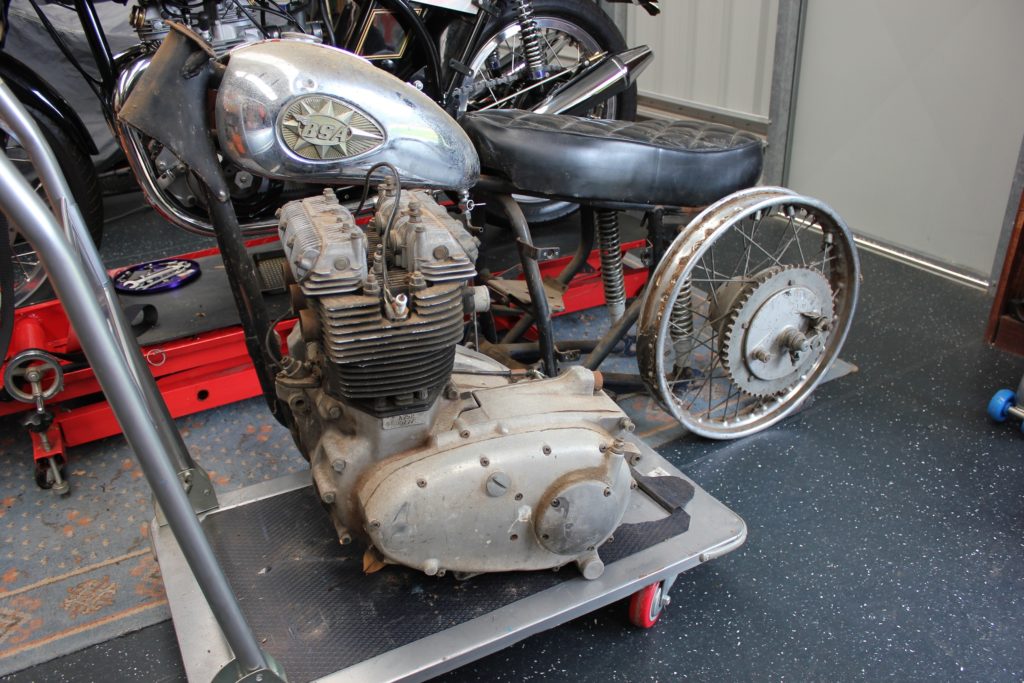

We have a Rocket 3 and it needs some TLC. In motorcycle restoration, this is what’s commonly referred to as a ‘basket case.’ Someone has pulled the machine apart, very likely with good intentions, but they haven’t got any further and the projects are quit – often at a bargain price.

Since arriving in the shed, the Rocket has been completely disassembled, not a huge task as readers will recall it was in pieces, large pieces. In the past few weeks it has been whittled down to individual nuts and bolts. Those nuts and bolts have been off to the electroplaters and a now sporting a lush coat of silver zinc.

Every nut and bolt was removed from the Rocket and catalogued with numerous digital photographs.

Disassembly revealed a rather healthy-looking engine that belies it’s 48 years. Certainly, the crank had never been touched, likewise the gearbox. I was starting to believe the indicated 5190 miles on the speedo might be accurate save for the presence of new pistons and valves in the top end of the engine. The bike was never started up following the .010” pistons being installed as they still bear a nice, shiny metallic finish. Why the engine would need new pistons and valve at such low miles is beyond me.

Plating has been carried out and all the fasteners are as good as new in silver zinc coating.

Some time ago, I began watching the price of a set of MAP forged steel conrods that would look great in my engine (if only you could see them). I watched eBay as our dollar tumbled and the price of the very expensive rods climbed ever so slightly higher, day by day. To put myself out of misery, in a moment of click-madness, I had spent $AUD990.

Click-bait – one click and you’re $1000 poorer. But worth it, these are almost too beautiful to put inside the engine.

The rods are a work of art and I would like nothing more than to match them up to some MAP pistons. Ordinarily, that would present a dilemma as I have three perfectly good pistons that have never been used, but, MAP don’t yet make pistons for Triumph/BSA triple engines – problem solved. Well, not entirely. I am reliably informed by MAP they will introduce new pistons for classic triples to the market this year. In my continual quest for the best components to put in my engine I’m just as likely to wait until I get my hands on three gleaming, new MAP pistons before I reassemble the engine.

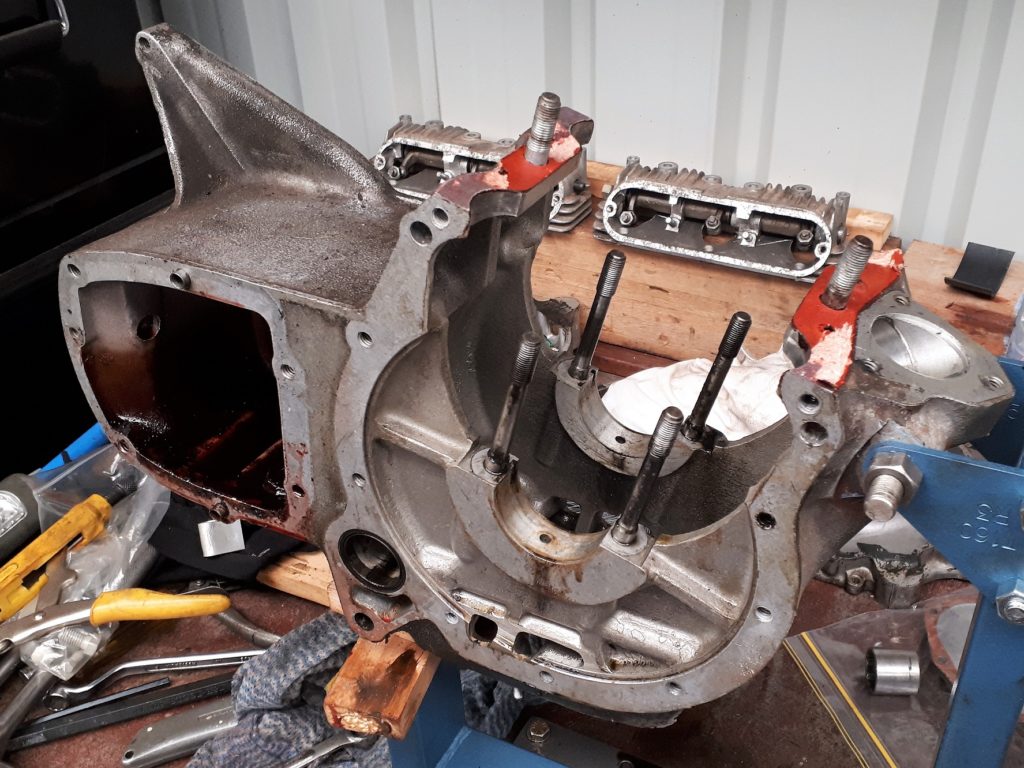

At the time of writing, the crank cases have been taken to the city to be cleaned and dressed, ready for assembly. I already have cleaned the cases with a high pressure cleaner and they came up reasonably well, which once would have been good enough but not anymore, I want this engine to look new and I’ve seen the work Ben does to old cases. I decided long ago I want a piece of that action so I happily sent my cases off for the treatment. They are not back yet but I’m confident the cases will be gleaming when I get my hands on them again.

Inn taking the head off the engine I found new pistons and freshly honed bores.

According to my readings, the crank measured up to be within tolerable allowances so I was content to leave it be and just fit new shell bearings. Ben talked me out of that. His philosophy is a little bit of cost outlay and work now can avert a major disaster further down the track. These engines are known for spitting rods out the front of the case so I’m easily convinced to take the extra precautions. Once fitted, the last thing I want to see is one of my precious MAP rods fighting for its liberation out the front of my beautiful, new cases.

Elsewhere, some of the tin-wear has been treated to a fresh coat of glossy black powder so we are moving forward but there’s some big cost items coming up and the Rocket is competing for limited fiscal resources in the Motor Shed. Lately the Mustang has been winning that battle.

The heart of the BSA Rocket 3, the 750 cc, three cylinder engine designed by Triumph and built at BSA’s Small Heath factory in South-East Birmingham.

The engine internals looked remarkably good, although I’m not sure about the wisdom in putting a new top-end (pistons and valves) on the engine without delving into what’s below.

New valves was a nice surprise was waiting for me when I took the head off.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 11, 2019 | Projects

This is a retrospective look at a project that was started in 1989 and finished about 25 years later. The reasons for the extended rebuild, well two rebuilds actually, are recounted in the book simply titled “Rebuilding the Ariel” and available on this site in eBook format. This story is an excerpt from the book.

I still vividly remember my first ride on the Ariel. It hadn’t been in our family for very long and Dad was quite pleased with having found such a good example of the iconic 1940’s sports bike. The Ariel was like nothing I had ridden ever before. Even before you start riding, the bike lets you know it’s different. The broad saddle, ‘tear-drop’ chromed and painted fuel tank with big rubber pads for the knees to prop against, bulbous front guard, an odd-looking instrument panel in the centre of the fuel tank are just some of the antiquities associated the motorcycle. Bakerlite switch-gear and an abundance of chrome-plating also let me know this motorcycle was different from the modern machines I was familiar with.

It was 1989 and the Red Hunter was the first “vintage” bike that I ever rode. In strict terms, the bike is not actually a vintage machine, it would need to be manufactured before 1931 to be deemed a proper vintage bike, but it certainly looked like one to me.

The 1951, 500 cc Red Hunter had plenty of power but the front end floated about like it was semi-detached from the rest of the motorcycle. The rear end was equally disjointed and, with the suspension beneath the saddle, the whole thing was a jaunty, wobbly and scary experience. I came away from that ride feeling the machine was confrontational. It had challenged what up until that time I believed motorcycling was all about. For me, motorcycle riding has an almost infinite range of variables between slow and easy right up to fast and exhilarating, with a whole lot in between. Riding something that was slow and exhilarating was completely new.

Make no mistake, these things were sports bikes for my father’s generation, they were the ‘Fireblades’ of their day. The Ariel was an affordable motorcycle that looked resplendent in bright red and sparkling chrome.

I recall thinking after my first dalliance with vintage motorcycling that it was an extreme sport for pensioners. They take their life into their own hands on many of the old bikes that often go like stink but handle like a sack of spuds and have little or no brakes. I’ve softened that view over the years as, although I’m a long way from drawing a pension, I’m increasingly enjoying being perched on top of old motorcycles.

The Ariel was taking its place amongst Dad’s collection of motorcycles that included BSA, BMW and Kawasaki machines. It was by far the most handsome and exclusive bike in the shed. Pretty soon after I set eyes on the Ariel, Dad said, “take her for a ride.” He didn’t say that very often so I jumped at the opportunity.

The bike was propped up on its rear stand. The stand itself is quite a sturdy piece of equipment that hoists the entire rear end up off the floor. In this position, one can safely sit on the bike with it upright and basically fiddle with it, which is exactly where I was when the instruction to take it out was offered. I started dabbing at the kick-starter, pushing the big long stroke 500 through its axis a couple of times, not expecting anything much to happen.

Clearly there was fuel in the tank, I knew that because it was seeping out of the fuel-cock, running down the line and dripping onto the magneto – which is a recipe for disaster and would need some attention in due course, but for now we’re off for a ride, just as soon as I can get this thing started.

International appeal! In a country famous for the re-creation of the English Royal Enfield motorcycles, Harjit Singh Dhanjal, of Calcutta, India, enjoys getting out and about on his Ariel Red Hunter.

I rose up on the kick-starter and gave it a stomp. At least that was the intention but, you don’t stomp on the kick-starter of a big British four-stroke single. You may stomp on a two-stroke, such as I was familiar with at the time, but the kick-start on a big single works best when its allowed to swing through its access in its own good time. As the kicker goes down, the engine draws breath, a big long gulp of air that passes through an ancient carburettor which, for the most part, seems to do a good job of shooting petrol in the general direction of the inlet manifold.

Ariel leathers worn by John Hancox, of Hancox Art, during his exploits racing single-cylinder Ariel motorcycles.

Anyone familiar with a good choke-hold around the neck (and, let’s face it, who isn’t?) would recognise that awful sucking, gurgling sound one makes attempting to draw what is seemingly one’s last breath. Similarly, in the case of the Ariel, the engine sounds like it is sucking and choking at the same time, then, all things being equal, a good rush of air and petrol vapour breathes into life into the big engine and a smoky, vibrating, chug-a-lugging has the whole bike dancing about even before a gear is engaged. It’s a strangely satisfying sound.

Over the years I became intimately familiar with the starting routine required to get the Ariel going in about one or two kicks. Usually, if the bike wouldn’t start on the third kick I would know something was wrong and commence an investigation. For now, I had the big 500 single rumbling away beneath me, a new appreciation for the internal combustion engine was building with the confidence that came from each explosion in the upper reaches of the cylinder block. I reckon I could count each one of those explosions. Twisting the throttle produced a healthy build-up of revs and an audible induction roar coming from the open Amal carb.

To get moving I had to stand up, feet planted firmly on the ground, and push the bike off the stand. In rolling the bike off the stand, the wide, tractor-seat styled saddle whacked into the back of my legs, plonking me back down in the saddle at roughly the same time the bike rolled to a stop. I dabbed and waddled the ungainly machine out of the shed (in hindsight, I believe I was the ungainly element).

If I felt clumsy and was sure it would look worse from where Dad was observing me, I feared he might change his mind about sending me off on his most recent acquisition so I figured I had better get out of there. I found the right-side gear change and pushed it down into first. Wrong. First gear is engaged by pulling the lever up. Fortunately I was on a bit of a hill so, combined with the long-stroking, lazy engine, it didn’t matter too much that I had selected second gear. A bit of a chug-a-lug and I was away, searching again for that right-side gear change.

Younger readers right now may be asking themselves “what’s a right-side gear change all about?” Back in the day, all bikes were right-hand change, then for reasons not clearly understood by the occidental world, the Japanese first came up with a left-hand gear shift and everyone else followed suit. Britain and Europe were happily producing the right-side gear change, whilst the US insisted on changing gear by hand, then, one-by-one, the various manufactures converted to the left.

Not exactly a Red Hunter, this custom Ariel was photographed on the Isle of Man in 2018 and is reproduced here simply to celebrate the sheer beauty of the creation.

The Ariel gearbox engaged with a rather sure clunk, and I gathered speed. “Clunk” is a great word and very descriptive of the Ariel gearbox. A solid construction of alloy and steel, the Ariel box is the same size as that found in a small, modern-day car. Whereas modern bikes tend to change with a ‘click,’ the Ariel always clunks into gear. Up into first – clunk, down into second – clunk, down again for third – clunk. Later, I would continue to use the clunk, clunk, method of moving between the gears then occasionally, in moments of panic, I would smash my way back up through the cogs in an attempt to wash speed off as the brakes were quite dreadful, but for now, back to that first ride.

The steering on the old bike was quite dreadful as the handlebars seemed to flop from side to side at will. Unbeknown to me there was a solution right at hand, in the form of a large bakerlite knob at the top of the triple clamps. The device is a damper that is used to literally tighten the steering. This is a useful device which is let down by the obvious flaw in so much as a rider has to remove one hand from the bars to reach across and tweak the knob. Even if I had been aware of the damping capabilities available at the steering head on this ride there was no way I was going release my white-knuckle grip on both ends of the handlebar.

Fast and affordable, the Ariel was the Fireblade of it’s day. Bolt Blyth has been racing his Ariel 500 for over 10 years with great success. We’ll be doing another piece on this race bike in the near future. Photograph courtesy of Bolt.

The farm-house sits on the side of a hill. It has a long gravel driveway that leads down past some sheds and onto the bitumen of the South West Highway. The drive-way intersects at the sheds and goes off to some cattle yards and shearer’s quarters. Very soon after leaving the home shed I noticed the strange handling characteristics the old bike seemed to possess. I also noticed the lack of brakes and that I had very quickly gathered some speed on the relatively steep gravel descent. During my youth I had frequently negotiated these roads at great speed – often sideways – on my motocross bikes but on this occasion I wasn’t feeling at all comfortable about the ride.

As I came upon the sheds, I opted to ride down towards the cattle yards because, up until that point, I had been going downhill and the route to the cattle yards flattened things out a bit, which seemed like the safer option. At the end of the road there was a turning cycle large enough to swing an articulated cattle truck around. Clearly, I was going to need every available inch of that circle as I was still coming to grips with the odd steering, suspension and poor brakes. The throttle cable was sticky and the brakes hardly worked but I managed to pull the monster up enough to make the turn and head back up the hill.

I was quietly relieved to ride the bike back into the shed and park it up, safe in the custody of Dad. I had ridden the Ariel one, perhaps one and a half kilometres that day. I was safe, the bike was intact, everything is okay, cool. Maybe it wasn’t that bad after all.

Readers might be happy to learn Ariel are up and running again as a low-volume manufacture. Using a 175 bhp, 1250 cc Honda V-4 engine, the Ariel Ace presents an aggressive stance with the promise of an exciting ride. Picture courtesy Ariel Motor Company.

by Dan Talbot | Feb 11, 2019 | Events, Racing

The hill climb is one of the oldest forms of motorsport and it is making a comeback.

I was lucky enough to compete in two hill climbs during 2018. Designated vintage motorcycle hill climbs, the term ‘vintage’ simply means over 25 years old. Obviously, by 1993 motorcycles had reached epic proportions of speed and reliability and to term bikes as vintage merely because they are over 25 years is stretching the definition and unleashing a turbo-charged 1000 cc Kawasaki, for example, is probably not in the spirit of vintage hill climbs. Having said that, I’m happy to report just about every one of the 85 entrants at the Albany event was manufactured before 1980 with the majority from the fifties and sixties. Likewise the York Hill Climb.

York wasn’t my finest hour. The Triton was running super-rich and oiling up the left cylinder to the point at which it was fouling the plug (bearing in mind this is single carb engine). I managed to pull some half decent times which was mainly due to the short course but about halfway through the run my engine would begin to misfire. It didn’t lessen my fun or excitement but I felt the engine, in not running at is optimum, was an insult to my tuning skills – which are limited anyway. All I had to do was get the bike through the event because here was a fix at hand: in England.

In June, whilst visiting the UK, my wife and I called in on the Morgo factory in Bradford where I picked up a new, big-bore 750cc barrel and pistons which would punch my Triton out by 100cc. I had purposefully kept my baggage to around 15 kilograms which would allow the weight of a full Morgo pistons and barrel kit. And two new Norton mufflers – but that’s another story. I didn’t need to go to the factory, I could have ordered the gear online but my bikes have so much Morgo gear tucked away their engines I kind of felt compelled to visit the place were the magic happens. I’m glad I did. My kit was packaged, waiting for me and the owner was touched that someone from Australia was visiting her business. Lynn, the owner of Morgo is the daughter of the late founder of the company and has been running things for the past four years since the passing of her father and by all accounts doing a fine job of things.

Morgo = more go! The 750 cc big-bore kit goes in, giving me 100 extra cc and Morgo bragging rights.

Extra cubes are all very well but they must be fed. Recall my comment above about not being all that well versed in motorcycle engine tuning? In rebuilding my Triton, I decided to retain the original single carb, 9-stud alloy head – as opposed to going to twin cards. To that end, I bought a new 36mm flat-side Mikuni carb from Mikuni Oz in Queensland. The Mikuni is a pumper style carb so it gives the engine an extra squirt of petrol when it’s most needed, i.e. when you crack the throttle.

Now there’s two types of people in classic motorcycle circles, Amal people and Mikuni people. I’m in the latter camp. The combination of the big-bore kit and the big pumper carb has my Triton running very sweetly so I’m willing to trade tiny bit English tradition for a big boost of Japanese performance.

My first big road bike was a 1977 Triumph Bonneville 750. The engine benefited enormously by fitting some larger, Mikuni carbs. Unfortunately the extra power was too much for the gearbox and I twisted the gearbox mainshaft in two. Twice.

I’ve yet to get the bike onto a dyno but for normal riding the Triton sounds and feels just like my first big road bike, a 1977 Bonneville which I bought new. In those days, incremental gains of one or two horsepower here and there seemed colossal in our never-ending search for more power and speed. It was like we were duty-bound to keep fettling the engine of our bikes to the point of blowing them up. After about two years of Bonneville ownership I fitted twin Mikuni carbs to the bike and had the inlet ports ground out to suit. The Bonny was transformed and for a brief time I enjoyed a healthy dose of horsepower – before I twisted and broke the gearbox main-shaft, twice. But I digress.

The Mikuni TM 36 pumper carb helps feed the 750 cc engine, bringing my Triton up to the same specs as the Bonneville I owned as a teenager. Mikuni Oz are in North Queensland and I recommend anyone struggling with tied, worn-out carbs to get in touch with Tom

By the time we got to Albany I figured I had the Triton well and truly sorted. Not so. The midrange was a bit flat but if I kept the reeves up high the engine hauled me up Mount Clarence in no short order. On my first run the bike almost cut out at the start line when it grabbed a great gulp of fuel and swallowed it whole. After a splutter, the engine took hold and launched me off the start line but it wasn’t enough to catch the Honda 750/4 that I was lined up against. I had much more success on the following three runs up against a Manx Norton. Before that however, I trundled off towards town and found a suburban hill, devoid of cars and shattered the Sunday morning peace whilst practising my hill starts half a dozen times. Satisfied I had perfected the art of the start, I returned to the hill climb to take on the Manx.

The legendary Manx is a highly-strung, highly geared, 500cc racing bike, not designed for drag racing up a hill but it’s oh so gorgeous and sounds sublime. I felt very privileged just to line up against a Manx so it was with some guilt that I beat it up the mountain on the three runs we shared. I felt even more guilty when the owner of the Manx sought me out specifically to offer to purchase my bike. I’ve had a few people offer to buy my Triton but I’ve yet to cave in to any offers and the Triton remains in the Motorshed garage.

My Triton shares its heritage with the Manx in the Featherbed frame made famous by Norton. Even the name is a contraction of Triumph and Norton. There is a story elsewhere on the Motorshed site as to how the Triton came into being which can be read here (https://motorshedcafe.com.au/the-triton/).

Alongside each other the bikes looked very similar. Naturally the Norton gives 250cc away to the Triumph engine in my bike but they both have a top speed of around 110 to 120 mph. The Norton gets there through a high state of tune and tall gearing, and that’s where I got the jump. The larger engine has more torque and therefore is able to get off the line quicker and climb better.

Both machines have an aggressive racing stance with a long reach to the clip-on handlebars and both were ridden by middle-age men who may not have been as flexible and subtle as we once were. Nevertheless, stretching out over the tank or a racing motorcycle allows a brief fantasy into the world of yesterday’s motorcycle racing champions, a feeling that is increased manyfold when we get to opportunity to actually race those bikes.

My practice starts revealed I could overcome the flat midrange by grabbing heaps of throttle at the start and riding the clutch to maintain the revs through first gear. Once in second gear with the throttle pegged, then again in third, the Triton came alive. When cranked into a sweeping righthand bend at full tilt, it never ceases to amaze me how Norton managed to design such a brilliant frame some 70 years ago. It feels rock solid and confidence-inspiring. In truth, the bike has much more to give but it would take a much better rider than me to explore limits of the Triton but, for now, I’m happy to make small gains in tunning, handling and, most importantly, riding ability.

The Triton and I, in our element. This photograph is by Andrew Haydock.

The perseverance, skinned knuckles and hours spent refining the bike over the past two years bore fruit on that day. At the top of the hill after each run I would join in with the other riders waiting to descend when the road was clear. Sitting up there, overlooking the bay with my engine clicking and clacking as it cooled, waiting for my adrenalin to return to normal levels, I was extremely happy with the performance of my ‘vintage’ motorcycle.

I reckon I’m ready to take it racing!

Photograph by John McKinnon.