Rebuilding the Ariel Part II

This is the second instalment from “Rebuilding the Ariel,” available on this site in eBook format.

Given this is only our second excerpt from Rebuilding the Ariel it is perhaps timely to have a brief discussion around the origins of the name Ariel. It’s no secret I love all things with two wheels, including bicycles, in fact, I have a particular fondness for the original bicycle: the penny farthing. There you go, it’s out there. I feel better having got that off my chest.

James Starley, the so-called ‘farther of the cycle industry,’ conceived the penny farthing and named it “Ariel,” after the character Ariel, the ‘spirit of the air,’ who was immortalised in Shakespeare’s sonnet “The Tempest.” In the Tempest, Ariel is a sprite who possess magical powers which, essentially, he uses for good. Ariel is powerful, agile and a loyal servant. It is easy to see how one may be inclined to name a motorcycle after such a character yet Starley chose this name some thirty years before the motorcycle came into existence.

Starley’s ungainly cycle, with its huge front wheel is neither powerful nor agile, however, one is indeed perched quite some way up in the air so perhaps that is what he had in mind. Starley’s hypothesis is as brilliant as it is simple. He found that by increasing the size of the driven wheel one could travel further with each turn of the legs. Naturally this simple form of mechanics was later made redundant through the advent of chain-driven gear system, another brilliant idea out of the Starley family, this time with the help of William Hillman, the founding father of the automobile that bears his name.

The new chain driven cycles were appropriately named the ‘safety bicycle’ as it put an end to riders toppling over the handlebars on out-of-control penny farthings, which were retrospectively named ‘ordinary bicycles,’ as opposed to the ‘unsafe,’ ‘dangerous,’ or ‘you must be crazy to ride this,’ bicycle.

Starley’s hypothesis is as brilliant as it is simple. He found that by increasing the size of the driven wheel one could travel further with each turn of the legs. Eventually, the wheel would grow too big for one to turn it. This is my old 55 inch wheel. I have now gone to a 58 inch Bolwell bicycle, which is a big wheel.

Starley passed away in 1881 leaving his sons to carry on the legacy of the Ariel although it was his nephew, John Kemp Starley, who also a member of the cycle production team that is credited with using Hillman’s idea to invent the chain-driven safety bicycle which was named the Rover, giving rise to the famous British motor vehicle company of the same name. Eventually the organisation became known as the Ariel Motorcycle Company with Ariel producing its first piston-powered machine in 1902, sadly after the death of Kemp Starley whose vision was firmly set on the motorcycle industry.

Shakespeare’s Ariel was said to be able to work up a storm, a tempest, sufficient enough to shipwreck the King of Naples and his crew. After providing loyal service to the magician Prospero, and having been freed from 12 years imprisonment at the behest of the witch Sycorax, Ariel is set free, hence, we have a loyal, powerful and free spirit giving its name to a motorcycle, presumedly with the same qualities. Now, back to our Ariel. We left off previously with me parking the bike up without having crashed it during my maiden voyage.

On reflection, I realise that Ariel was like nothing I had ridden ever before. Even before you start riding, the bike lets you know it’s different. The broad saddle, ‘tear-drop’ fuel tank with big rubber pads for the knees to prop against, bulbous front guard, an odd-looking instrument panel in the centre of the fuel tank are just some of the antiquities associated the motorcycle. Bakerlite switch-gear and an abundance of chrome-plating also let me know this machine was different from the modern machines I was familiar with.

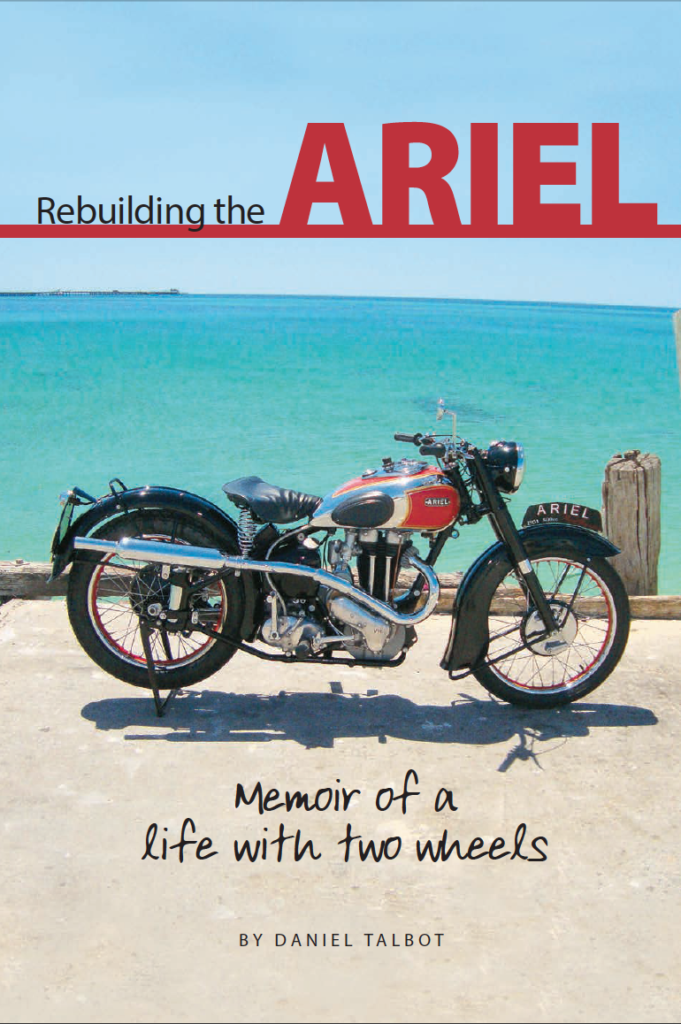

When introduced to the Ariel I was still at the age where performance and looks counted for a lot in a motorcycle and, to me, the Ariel had neither. As I write this piece, almost three decades since that first trepid ride, and with lots of equally hair-raising and fun times spent on the Ariel, I now tend to think it is perhaps one of the most handsome machines ever made. Red paint upon chrome, gold pin-stripe and a black frame, add up to a visually stunning motorcycle. Take a look at the photographs and tell me you disagree (comments are welcome in the box below).

Back then, I loved dirt-bike racing and road-riding with equal measure, I still do, but in recent times I’ve returned to the more pure form of cycling – that which is without an engine. I trust these pages will attest to my twin passions of motorcycling and bicycling, for me, it matters not how much power is contained within my machine, if it’s on two-wheels I’m all for it.

Around the time I took my first excursion on the Red Hunter, I was quite heavily involved in bicycle racing and triathlon. I still love my cycle racing and can think of nothing better than to flog myself for six hours on a bicycle and, to do any good, we must train, which means I often spend more time riding bicycles than I do motorcycles.

Yep, we race bicycles – including these.

We race motorcycles too. If it’s got two wheels we’ll give it a go.

As I write this (wrote this), with the Ariel undergoing restoration (now finished), I wonder if it will see any more use than the half a dozen rides per year that the two other operational machines in my garage get to see. My friends jokingly comment I need a new battery every time I want to ride my modern Triumph. The older Triumph has a kick starter so a flat battery doesn’t prevent me from riding it. It makes little difference to me whether I ride my motorcycles or not, the important thing is they are there, ready to go, should the urge take me. I also like my bikes to be in top condition, even if they are dormant, and the Ariel has been in a rather poor condition for some time now. Postscript; there is now seven motorcycles in the shed and they still battle against my bicycles for time in the saddle.

Dad purchased the Ariel sight unseen out of Tasmania. As stated earlier, he bought it because he had one when he was a young fellow. The Red Hunter was one of the more desirable motorcycles of his era and about the time Dad turned 17 years of age he managed to secure a very nice example out of Bays’ Motorcycles in Perth. Evidently Dad’s father paid for his first Red Hunter so it’s fitting that I have managed to purloin this example from his grasp (more on that later).

By the time Dad acquired his first Ariel, the Red Hunter had been in production for about 20 years, having made a stunning debut at the Earls Court Motorcycle Show in 1931. The Red Hunter came in both 350 and 500cc variants and was known right from the start as a sports machine. That Ariel remained in production through two world wars, the Great Depression and some major company restructuring speaks volumes for the durability of the machinery produced by the company. In a further demonstration of durability, the official production run for the Red Hunter was 27 years, from 1932 to 1959.

Despite the Ariel being both a capable and desirable motorcycle, what Dad truly longed for was a Triumph Thunderbird. With its larger 650 cc twin cylinder engine, the Thunderbird was known as a true superbike of the era, capable of 100 miles per hour. As it turned out, he would have to wait another 40 odd years before the Thunderbird dream was to be realised.

In 2019, I’m happy to attest both the Ariel and the Thunderbird remain with me.

To be continued, or you can buy the book, in eBook or hardcopy format.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks