by Dan Talbot | Jan 13, 2019 | Projects

Triton motorcycles were not factory models but were hybrid bikes built in the 1960s and 1970s. Many were privately constructed but some London dealers offered complete bike. The builders fitted Triumph engines into Norton frames, and the aim was to combine the best elements of each marque and thus gain a bike superior to either (Wikipedia).

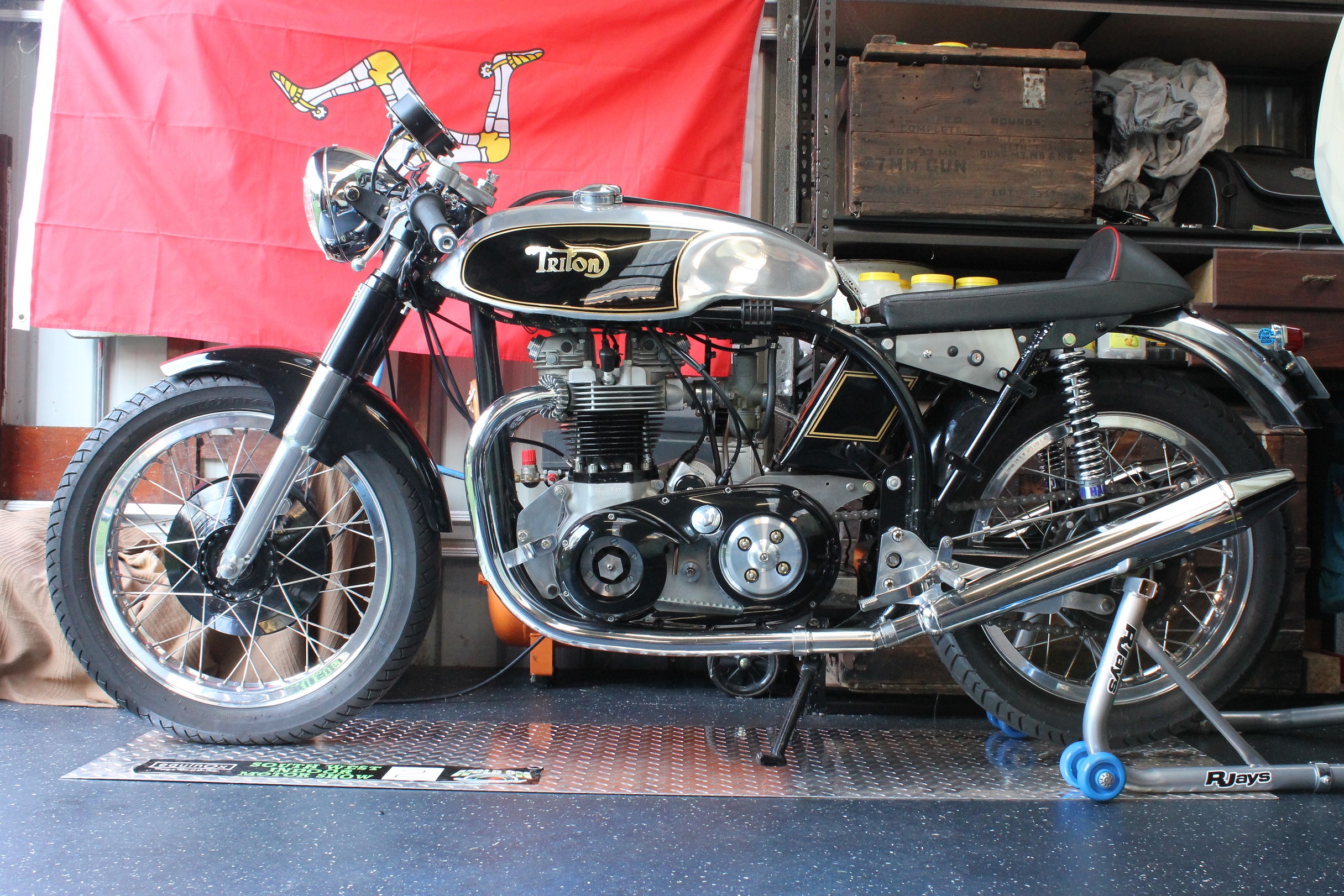

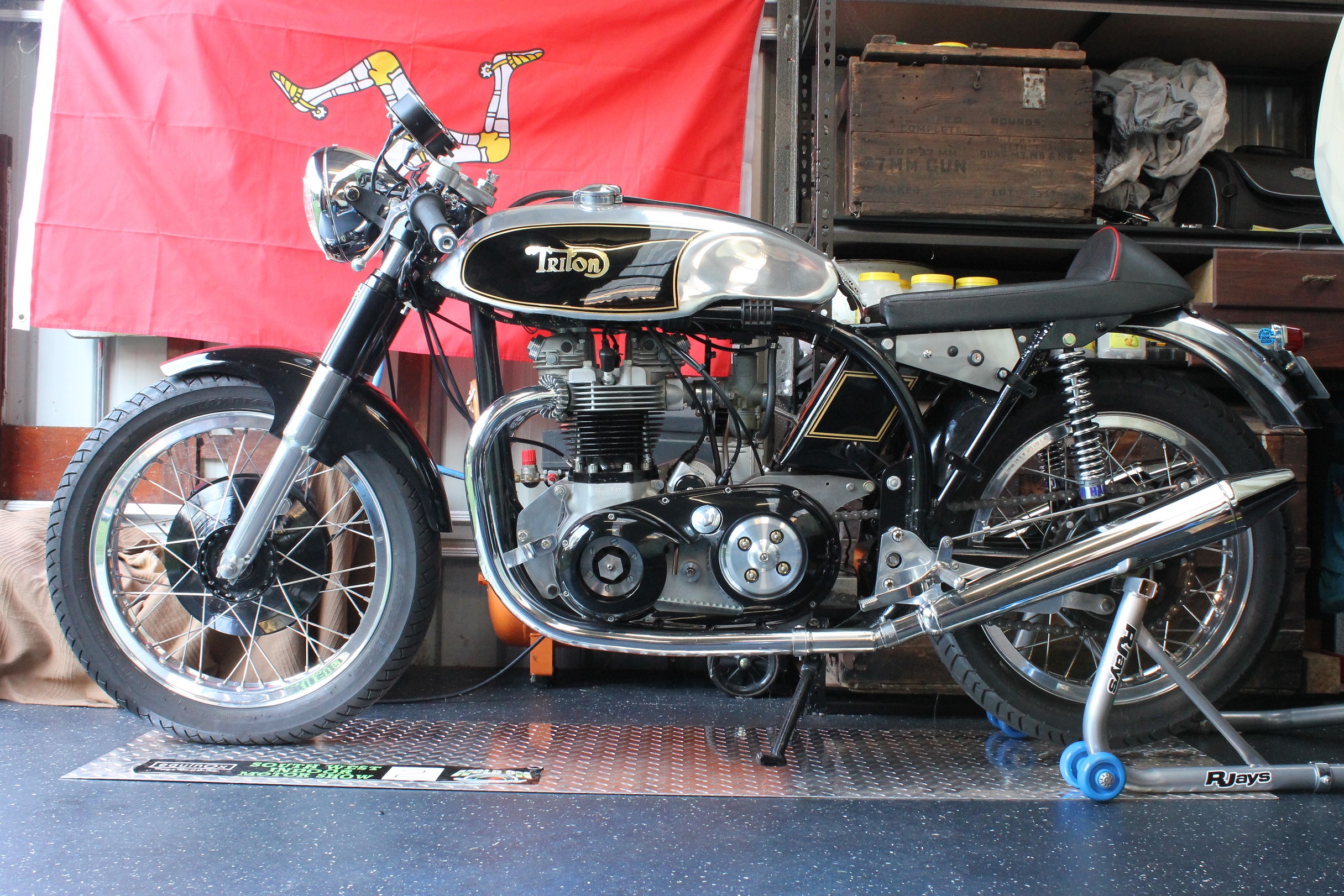

My Triton came to me as an unfinished project. It had never been licensed and the engine had only been started briefly to make sure that a) it actually ran and b) it didn’t leak oil (well not too much anyway). The bike was fitted with lots of bespoke parts, most of which didn’t agree with my tastes and would find their way into the parts bin.

Photo by Graham Hay.

Triumph and Norton are the two best known names in the British motorcycle industry, both of which have been with us on and off for well over 100 years. If I may be so bold as to say during that period Triumph have emerged as the everyman’s motorcycle whilst Norton are the clubman’s machine, evidenced in the Manx racing motorcycle. The Manx Norton is one of the best examples of Norton asserting the company as the racer’s choice.

In the post-war motorcycle world, the British were intent on reaffirming their place at the top of the sport, but first they had to win at home and the machine designed to do this was the 500 cc Manx Norton. Even today, the Manx still sends hearts fluttering with its stunning performance and dead-sexy styling (for me anyway).

Despite the Manx engine being a ripper, by the late forties Norton recognised they needed a better frame. They employed specialist frame builders, brothers Rex and Cromie McCandless, who set about developing a frame specifically for the Isle of Man circuit – it is a Manx Norton after all.

Lined up against a genuine Manx Norton at the Albany Motocycle Hill Climb. Note the similarities between the Manx and my Triton.

The new bike was rolled out in 1949 and made its debut in 1950 whereupon Norton works rider Harold Daniell declared the new frame was like “being on a featherbed.” Since that time, Norton’s double-cradle, welded steel frame has been known as the ‘featherbed.’

Harold came 5th in the 1950 Isle of Man TT (Tourist Trophy) but the first three riders were all on Manx Nortons, the die was cast, Norton would dominate the Mountain circuit for the next five years. Norton’s winning reputation wasn’t lost on the four-wheeled racing fraternity either with the Manx engine increasingly founding its way into the Formula 3 open-wheeler class. Norton wouldn’t sell the engines on their own so for every racing car that was built a functional rolling chassis was pushed aside, until, that is, some enterprising person thought to install a larger Triumph twin in the hitherto defunct featherbed chassis.

In the late forties, early fifties, the world was craving larger, twin cylinder machines so a reverse-symbiosis that produced both a small racing car and large-capacity motorcycle was ideal.

My Triton is not one of those machines, it is a modern-day re-creation, a combination of alloy from a bygone era and modern steel. The engine was once in a 1956 Triumph Thunderbird although it has been tweaked considerably since the engine found its way into my possession.

Whilst the Triton is founded on mid-twentieth century parts-bin specials, there has been a renaissance and specialist manufactures who are turning out what are essentially new bikes. Made in Metal and Dresda are two manufacturers worth having a look at for some very nice machinery. Elsewhere, in the ultimate testament to the enduring nature of an almost 70 year-old design, people are putting modern Hinckley Triumph twins into featherbed frames.

In a modern touch, my Triton uses a hand-made replica featherbed frame made by Ken McIntosh in New Zealand. To the untrained eye, indeed to many a trained one too, my frame looks like the original item except it’s made from modern tubing and advanced welding techniques that weren’t available to the craftsmen of old. Replica featherbed frames are common-place but they vary in quality.

Original featherbed frames can be bent, broken, rusty and fatigued. My frame has never been cut, crashed or cartwheeled (yet). It’s a top quality, strong piece of kit that is taunt and tracks brilliantly when pushed hard. Indecently, a McIntosh bike currently holds the record for the fastest lap of the Isle of Man by a Manx Norton in the hands of Kiwi rider Bruce Anstey.

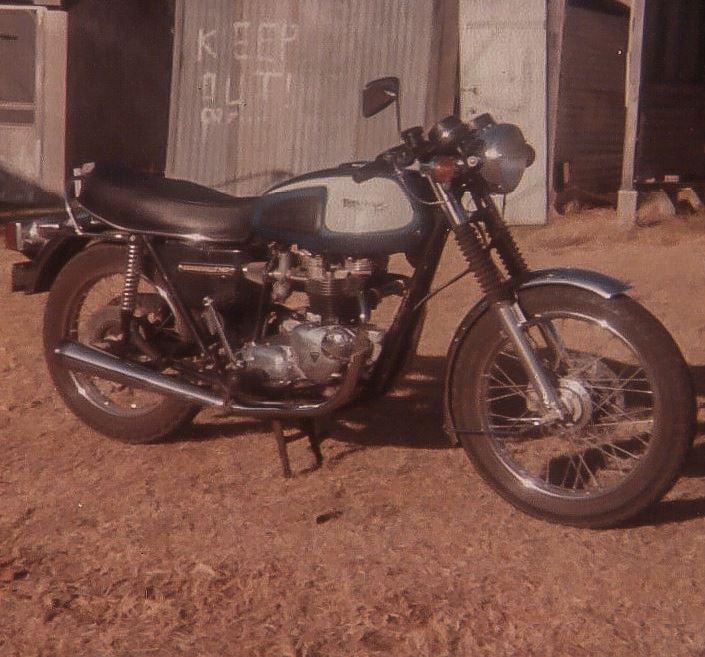

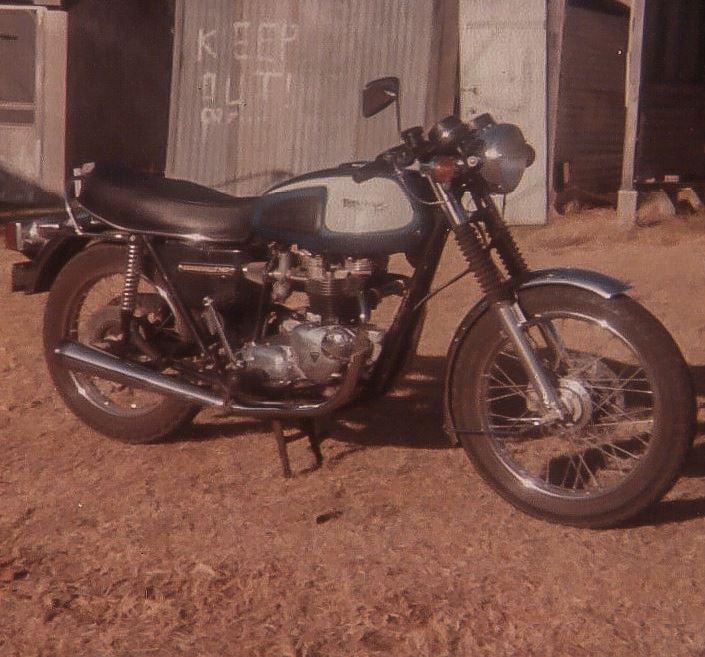

I have owned a 1956, 6T Triumph Thunderbird for many years and before that it belonged to my father. Back in the late 1970s Dad and I both rode 750 Bonneville’s, they were great days on great bikes but we moved on and our Triumphs were eventually consigned to memories, until 1997 when Dad spotted the T-Bird and decided we must have it!

The Thunderbird preceded my Bonneville by 21 years. It’s heavier, longer and lower than the Bonny, steers slower and naturally has less power. I used to think “if only I could get this thing around a corner” and began to appreciate the idea of the Triton. My mind increasingly turned towards building such a machine but conflicting emotions would take hold whenever I contemplated how much of the Thunderbird would be consigned to the rubbish pile after I robbed the engine for service in a Norton frame. Cognitive dissonance is a great motivator for doing nothing. Aside from being road-going, national treasures, classic Triumphs are aesthetically pleasing and trending towards the valuable.

My 1956 Thunderbird – too beautiful to pull apart to construct a Triton.

No one is going around urging owners to junk functional bikes to make hybrid specials, to the contrary, I would probably be picked out of the classic motorcycle club to which I belong should I even begin such a project. And, as if I need any more reasons, one of my favourite photos of my late father depicts him sitting on the Thunderbird with his trusty Border Collie alongside. No, if I wanted a Triton I would need to build one from parts or find a fully assembled machine. I ended up settling for something between the two. As mentioned earlier, the engine was originally in a Thunderbird, indeed, the engine number in the Triton is so close to the one in the Thunderbird they could have been bedfellows.

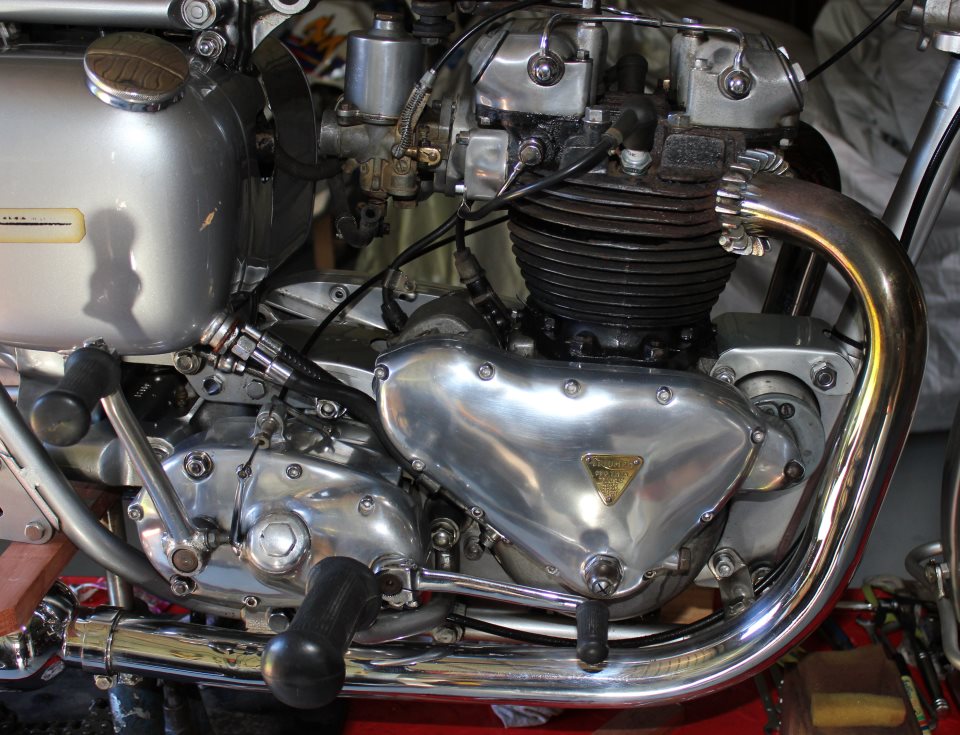

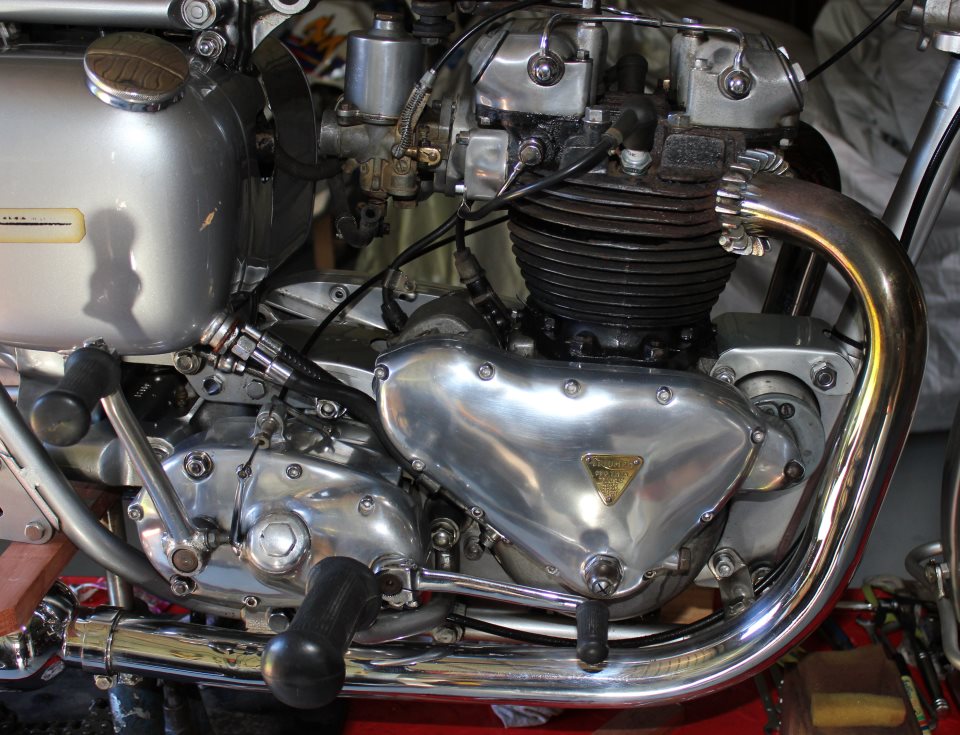

The engine in the Triton’s is commonly referred to as a ‘pre-unit,’ meaning the engine and gearbox are separate units. In 1962, for the first time since being introduced in 1937, the engine and gearbox were joined together in a common crankcase and were thereafter referred to as unit constructed engines. Unit constructed engines are more compact and somewhat lost in the feather bed frame compared to the older pre-unit items. Debate goes on as to which is the engine best suited to the Triton but it simply boils down to personal preference.

This is the engine in my Thunderbird. The gap between the engine and gear-box denotes this as a ‘pre-unit’ Triumph.

Triton aficionados and café racer tragics will recognise this bike has a host of refinements, including the highly desirable combination of Norton Roadholder forks, Akront alloy wheels and a four-leading shoe drum brake. What’s not so recognisable is the five-speed gearbox, belt primary drive, what is not so evident is a host of improvements hiding below the surface which will be discussed further in separate links.

Evidently my bike had been sitting for some time, it was covered in a good layer of dust and had the obligatory puddle of oil under the engine but, despite the neglected appearance, it was obvious the machine had the goods. The engine was held together by all new fasteners and, brushing the dust away, the cases looked bright and new, clearly having been blasted prior to reassembly. The lack of oil on the external engine surfaces, save for the sump at the very bottom, confirmed it probably had not been run for any length of time since assembly. The presence of little rubber knobs on the Dunlop TT100 tyres reinforced this.

The bike had been put together by a couple of legends of WA motorsports, one a mechanic, one a racer. Both are now in their eighties and still going strong. I hold onto visions of two old motorcycle wizards tinkering into the night working on their creation over cups of tea, which adds to the romance of a Manx-bred racing machine.

I had great confidence in the quality of the build which, by and large, remains with me however I must say I have rebuilt just about everything on the bike, either through necessity, performance experimentation or simply my desire to customise the bike to my tastes.

It is a rolling test bed for me to refine and tinker with before I take it out for a good thrashing. Stay tuned for reports on various events where I’m permitted to ride the bike in the environment for which it was intended, the race track.

-

The Triton as she stood at the time of writing. Photo by Jeremy Hammer.

by Dan Talbot | Jan 5, 2019 | Projects

From about the time my adolescent hormones started to make themselves felt, I began to hear tales about Vincent motorcycles. Then, as now, my preference was for an Egli Vincent, which is the creation of Swiss motorcycle racer Fritz Egli, who, upon finding he had reached the upper handling limits of a standard Vincent frame, turned around and built his own, to which he fitted the famous Vincent 1000cc twin engine.

Egli’s frames are distinctive insofar as they have a massive, tubular backbone and no cradle. The engine hangs from the frame and in fact forms part of the frame in an engineering practise often referred to as a ‘stressed member.’

This is the machine we’re after – well, close anyway. The photographer is unknown.

It should come as no surprise that engines from the fastest, most expensive, most exclusive motorcycles on offer throughout the fifties are not exactly lying around gathering dust waiting for Egli Vincent fans to stub their toe on. Nope, they are as rare as rocking-horse poo. Luckily, I have a plan.

Triumph motorcycles are a passion that extends back to my teenage years because those same adolescent hormones that were bouncing about at the thought of a Vincent Black Shadow also had to compete against the Triumph Bonneville. I remember the first time I saw a gleaming gold Triumph Bonneville as clearly as if it was yesterday. It was in fact 1974 I was on holiday at the seaside town of Augusta, South-West, Western Australia. That Bonneville changed my life and I knew one day I would own one. In hindsight, I didn’t have to wait all that long, by the time I was 18 I had my first Triumph and a life-long relationship with the brand was commenced.

My first big, road-going motorcycle, a 1977 Triumph Bonneville 750 T140.

Naturally, my first Triumph was a Bonneville. I say ‘naturally’ because then, as now, the name Bonneville is synonymous with Triumph, for me there simply was no other choice. By the time I purchased my bike the venerable British twin had grown to 750 cc, had disc brakes front and rear but essentially, it was the same engine developed by Edward Turner some 40 years earlier in the form of the 500 cc ‘Speed Twin.’

At the time, unbeknown to me, Triumph had also built a 3-cylinder motorcycle. Such was my lust and determination to own a Bonneville, I was blind to the rest of the range, which is just as well because the Triumph Trident was way above my teenage, apprentice budget but destiny has a funny way of working things out.

Like most motorcyclists, my bike-radar goes off in all sorts of directions and the Egli Vincent has always been there. Last year I came very close to paying $5,000 to two pieces of Vincent crankcase from a 1955 1000cc V-twin. I was outbid at the last minute and immediately felt a wave of relief. Such is the value of classic Vincent machinery, I could have bought brand-new, freshly cast reproduced Vincent cases for about the same price, but they would be from this century, which kind of defeats the purpose.

Then, in a rush of blood to the head, I decided to build an Egli Trident. In the recent two or three decades Egli frames have been fitted with all manner of engines – even Triumph triples, although they are rare. In truth, a Trident engine will be faster, more reliable and sound better than a Vincent.

I started my research and a couple of frame makers started to emerge from the cyber jungle. They were Patrick Godet and Colin Taylor. Godet was in fact building complete, fully assembled Egli Vincents. Egli himself had endorsed the Godet machine that was made up completely from new parts. It is a modern motorcycle based upon a 70-year-old design, and it’s a thing of beauty. I wrote to both Patrick and Colin with my idea to build an Egli Trident. Colin wrote back. He was enthusiastic and helpful.

Sadly, Patrick Godet is no longer with us but his legacy will remain strong with many of his fine machines scattered around the globe.

Colin Taylor’s bread and butter is, of course, Egli Vincents but he’s willing to tackle anything. His enthusiasm was infectious and after receiving my deposit from across the equator, Colin got to work and the Egli Trident project swung into production. There was just one problem – I didn’t have an engine. Furthermore, you’re probably thinking, “what exactly is a Trident?” So, lets take a look at the British 3-cylinder engine that changed the world.

The heart of the BSA Rocket 3, the 750 cc, three cylinder engine designed by Triumph and built at BSA’s Small Heath factory in South-East Birmingham.

The Triumph/BSA 3-cylinder engine had been in planning and design for almost 9 years before its release. Triumph engineers Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele were the fathers of the triple. Singles and twins were common place in the British industry but there was a growing demand for faster and more powerful machines, particularly to feed the demand from America.

This presented a problem. The larger and more powerful twins became, the larger and more pronounced the vibration became. In hindsight, the progression from single to twin to triple seems logical, but it took Hopwood and Hele to bring it to fruition.

The Triumph prototype engine was completed in 1965 and the Trident could well have gone into production by 1966 but parent company BSA wanted part of the action. Not content with badge-engineering, BSA insisted on making a triple of their own and this is where things get a little ridiculous. The Triumph triple cylinder engine was built in the BSA factory at Small Heath, it was, for all intents and purposes a BSA engine. In following naming conventions of the day, engines destined for Triumph were stamped with the prefix T150. BSA engines were stamped A75. That’s easy, no problem there, except to see the difference between the engine prefixes one almost needs to get down on the ground to read the stampings.

It was decided the BSA engine would need a distinctive look so the barrels on the BSA unit were canted forward by 12 degrees, which (kind of) dissociate them from Triumph. The right side timing and gearbox outer cases were also altered to provide another individual touch to the BSA item. Think of designing something that is basically the same yet requires re-tooling, casting, machining etc and the simple act of making minor changes becomes a major undertaking. Luckily, the internals remained the same between the two engines, as did just about every other piece of the triple.

With the engine (almost) uniquely styled to BSA, it became apparent the Triumph duplex frame was would not support the forwarded slanting engine so the BSA would need a new frame too. Conveniently, Triumph would later use the same set up to allow inclusion of an electric start behind the barrels of their 1975 T160.

The finished product would add two years to the release of both bikes and BSA Triumph missed the opportunity to unleash the first mass-produced superbike onto the world market. Honda stole the show. The Brits had been caught resting upon their laurels. They were the motorcycle super-power of the time and probably expected to remain as such.

Triumph and BSA triples were winning production racing around the world, including the two most famous races of the time, the Isle of Man and Daytona. BSA dominated the American AMA competition well into the 70s but sales of the Japanese bikes sored, whilst sales of the British machines stagnated.

Possibilities are endless. This custom made bike uses a BSA Rocket 3 engine in a frame built by Les Whiston, of Rob North Triples, in the West Midlands, UK. The photograph supplied by the owner of the motorcycle, Mr Carl Cookson.

The bikes generally remained the proclivity of purists both then and now. With fewer bikes produced, BSAs command higher prices, which leaves Tridents as representing excellent value for money in classic motorcycling collecting.

In my search for a Trident, I uncovered a gem in the form of a ’71 Rocket 3. It is a basket-case but it’s all there and it’s the more appealable Mark I, American-styled BSA, rather than the boxy English design by David Ogle, who was more accustomed to designing radios, toasters and a thoroughly awful car. The Rocket is too valuable to separate its engine from the frame so it will become a project unto itself. https://motorshedcafe.com.au/rebuilding-the-rocket/

My ‘basket-case’ Rocket 3.

Elsewhere, in the same shed that I uncovered the Rocket, a few old Triumph Tridents rest gathering dust. One of those machines has been tagged as a donor to the Egli Trident Project.

Over the coming months and years, I will begin to bring the pile of dusty, rusty BSA parts back to life with my mantra of painting, plating or polishing every surface of the machine. Moving parts will be assessed and, if need, replaced. Likewise, the Egli Trident will also take shape. It wasn’t my intention to commence two projects but serendipity visited the Motor Shed so I’m basically committed to reviving a piece of British motorcycle history and creating something new, albeit with an engine from 1974.