Vincent HRD owner’s review

10,000 kilometres

By Dan Talbot

Mercury is the God of eloquence, merchants, travelers, thieves and wisdom. I’m not sure why the Romans threw thievery in there but, in his defence, Mercury was the father of Cupid and one of the Olympians so that must give him some kudos and may help explain why I am so taken by Vincent motorcycles. It is little wonder Vincent emulated the Isle of Man TT trophy of Mercury rising upon a motorcycle wheel as their tank motif. Mercury takes front and centre when I’m sitting on my Vincent gazing upon the beautiful work of master engineers from the middle of last century. He reminds me of how lucky I have been.

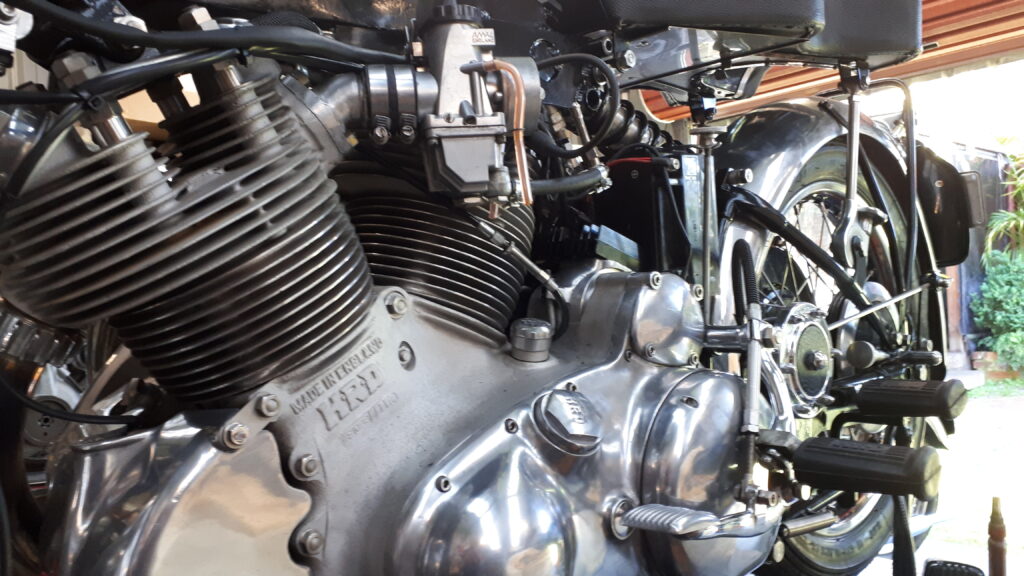

Over two years and some 6,000 miles (10,000 km) down the track of Vincent ownership, I figured it was about time to write an update on where I am at with my 1948 Vincent HRD Rapide. There has been a few trials and tribulations associated with my machine but this was perhaps to be expected due in a large part to me purchasing a motorcycle that had covered only a few miles since it was restored. At this point it would be useful to read my earlier piece introducing the Rapide back in 2019.

Fresh of the docks in Melbourne (the bike, not me). As soon as I was able, I flew to Melbourne to check out my Vincent, the realisation of a 40-year dream.

When I took delivery of my Vincent I (foolishly) expected I would be able to get it registered and ride off into the sunset. Naturally this never happens with a new restoration and it has taken quite a lot of fettling to get things right. Aside from the obvious frustrations that will unfold below, bringing my motorcycle into a ridable state has been a tremendous learning curve, that I am only beginning to climb. There’s an adage out there that says “Norton, making mechanics out of motorcyclists.” I won’t argue with that, my Norton problems are well and truly documented but one could easily transpose ‘Norton’ with ‘Vincent.’

My Rapide arrived with Mikuni carburettors. Mikunis are a very good hardware and I’ve used them to great effect on other British motorcycles I’ve owned, including my Triton. The Triton has a massive, Mikuni pumper carb and she flies. Again, there was lots of trial and error in getting that machine running correctly and some of the lessons I learned in tuning the Triton’s old pre-unit Triumph engine would later be applied to the Vincent. I had dreamed of owning a Vincent for over 40 years and during that time had devoured countless books, magazines and, more recently, online resources. I could close my eyes and vision the machine I would one day own and never once did it have Mikuni carbs. On my Rapide they hung there like transplanted dog’s bollocks and I just couldn’t get my head around them. I needn’t have worried too much, the Mikuni’s had a built in obsolesce in that the bike was not running very well under their stewardship. It was an easy decision to dispense with them.

Not for aircraft nor Vincent.

A friend sent me a pair of Amal Mk2 carbs he had removed from his Vincent when he bombed it out to 1200cc. At one litre, Holger’s Vincent ran well with the Amals but when he went for the big-bore kit he opted for a pair of larger, pumper carbs which left the Amals looking for a new gig, enter the awakening. The rub here is that Amal Mk2 carbs were made under licence to Mikuni. So here I was, removing perhaps the world’s most reliable carburettors from my motorcycle to replace them with a dodgy British imitation. Mad, I know. It didn’t work either. I persevered with the Mk2’s for far too long but could not get the machine running right (nor could some experts well versed in the art of motorcycle tuning). I even changed the ignition from Pazon to Trispark, but that didn’t help either. Eventually, a friend offered me a pair of brand-new, unused Amal Premier carbs apparently jetted for a Vincent twin. They worked a treat but not without some radical changes to the manifolds.

For a time, I hoped Amal Mk2 carbs were the answer. Sadly after a great deal of time and money neither myself nor people ‘in the know’ could get these carbs working. They were subsequently set aside.

The solution came in the form of two brand new Amal Premier carbs.

The Mikunis and Amal Mk2 use rubber sleeves to hold the carbies to the manifold stub. The carbs held in place by worm drive clamps. The Amal Premiers, on the other hand bolt up to manifolds, which in turn bolt to the heads. Such is the design of the Vincent engine, the two manifolds have subtle differences to accommodate the correct angle for the carb to sit at. That is, each manifold has a different angle. In fact, the manifolds had enough angles to confuse Pythagoras. Now, I am no mathematician, but two manifolds, each with two surfaces, equals eight possible combinations, there may as well have been 800, there was no way I could get the rear carb to sit correctly. Eventually, I went off on a ride, a long ride, with my wonky carb. Sitting at a pub having a lunchtime beer, a fellow enthusiast voiced what I knew to be true, “that doesn’t look right.” “No, it doesn’t. Hold my beer.”

Amal carb listing.

Off came the carbs again and more moving and swapping of the manifolds took place, this time with about six very experienced classic motorcycle enthusiasts present, two of whom owned Vincents and they too were stumped. I made it home but, in the end, out of shear frustration, I cut the manifold in half, reset and marked where I wanted the flange to sit and trotted off to a welder. The result was infinitely better, but still not quite right. I needed balance.

Aside from Zen, what I needed was for the carbs to open and close at the same time. I decided I needed a pair of mercury gauges. Seems reasonable, a factory decal of Mercury riding upon a wheel sits in the middle of every Vincent fuel tank. Whilst waiting for the delivery of my mercury gauges, in a nod to Heath Robinson, I used a makeshift setup that involved placing a long meat skewer under the slide of each carb (I can hear the moans, but stay with me). I set the Amals to raise and lower the skewers in unison. Then I had it – a perfectly running 1000cc V-twin engine! Off I went.

I can hear the groans from here. That said, my rudimentary carburetor synchronising tools worked. Eventually I had a perfectly running V-twin engine.

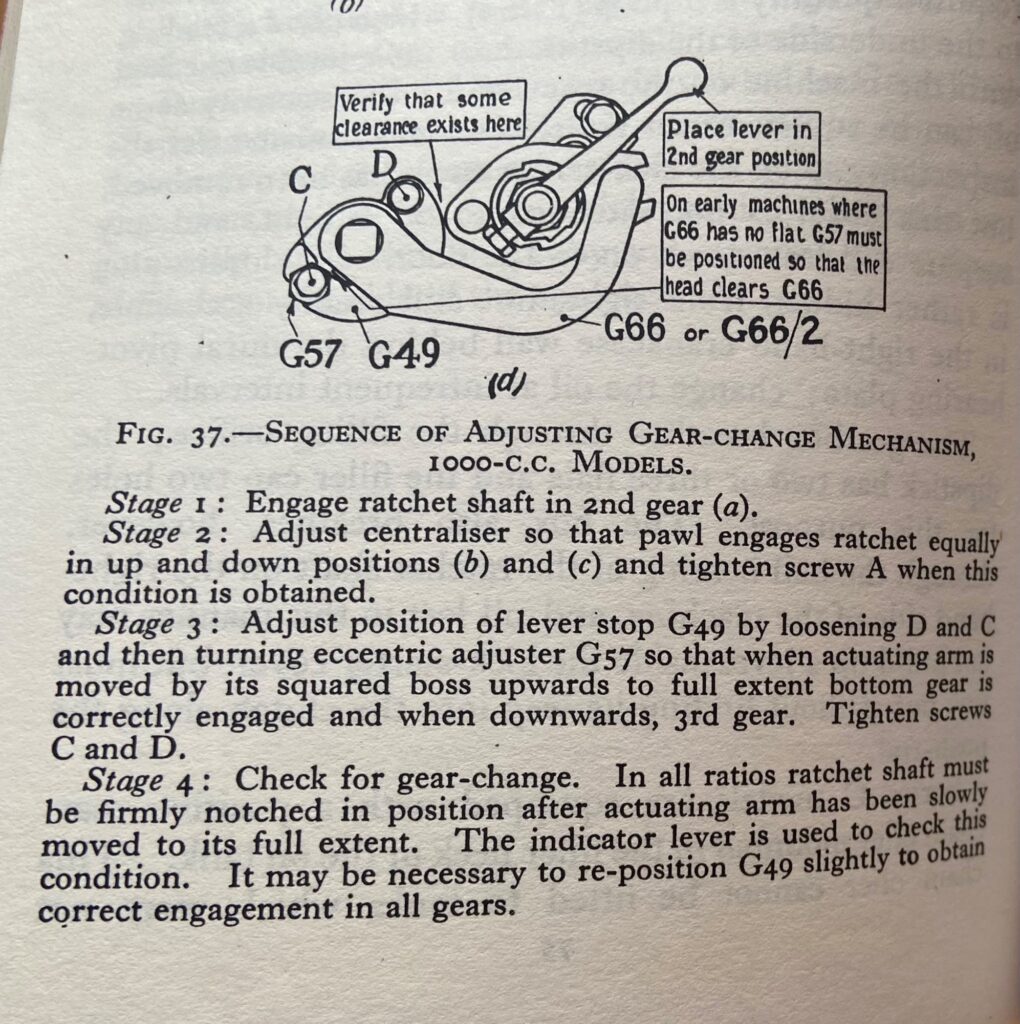

About 20 kilometres from home I lost second gear. There was no grinding or crashing coming from the gearbox so I headed off home. Gear selection was hit and miss but I made it. Having arrived home, I hit the computer and found out what the problem was. I set about rectifying the wayward gear selector according to the brightest and best mechanics google turned up and promptly lost all my gears. Long story short – I turned to the Paul Richardson’s 1955 book Vincent Motor Cycle Maintenance. There is a four-stage process that takes one through the correct setup that, on this occasion, was lost because of a loose bolt on an internal adjustment device called a ‘pawl,’ but mostly referred to by the Vincent Illuminati simply as ‘G59.’ I was beginning to understand everything in Vincent nomenclature was defined by part numbers. To this new owner, it’s equal parts civilised and alien.

And that’s how it’s done.

With my gears sorted, I ventured out again, but not before having a crack on a forum about Vincent letting the work-experience kid engineer the gear selection mechanism. I was rigorously chastised by the Illuminati putting me firmly back in my newby box. The mere act of turning up on a forum signals one’s vintage along the road of Vincent ownership and I was called out as inexperienced (true), incompetent (in my defence, I was mobile) and inorganic. I’m not sure where that last one came from, maybe someone thought I was a cyborg, or, maybe spell checker jumped from ‘ignorant’ under the furiously tapping, albeit arthritic, thumbs of a Vincent enthusiast. In any event, 6,000 miles later and there’s been no more troubles from the gear selection, save the occasional jumping out of third gear, so my crack at the work-experience kid was probably not warranted.

The next big thing was the clutch. My Vincent was fitted with a late-model, replacement clutch manufactured under the banner of V3. The V3 clutch is a gem. It simplifies what was a complicate servo unit that the faithful will defend to their last breath but those of us who actually want to put miles on their Vincents invariably turn to an after-market clutch. Soon after I got out and about on my Vincent the V3 began slipping. The problem was eventually found to be the lockring, hang-on, the G45, that holds the gearbox main-shaft bearing in place. This allowed the main-shaft to gradually drift to the left against continual adjustments by me to the clutch in a futile attempt to lessen the slipping. When the lockring finally came all the way out I lost any semblance of a clutch and the bike had to be trailered home. That the gearbox suffered no lasting damage seems to confirm Richardson’s 1955 assertion they are ‘unusually robust.’

A brilliant piece of Vincent kit manufactured by Paul Alton in France.

I’ve touched on the ignition above. The changeover from Pazon to Trispark was driven by equal parts experimentation and frustration during early ownership of the Vincent. In hindsight, it probably wasn’t needed. Pazon is a perfectly good product, and so too is Trispark, but they rely on a power source. My ignition preference is the magneto. A magneto generates its own spark so the engine does not rely on a battery. Back in 1948, when it was new, my Vincent had a magneto and I would like to revert back to one, albeit a brand-new, modernised unit. However, the bike is running beautifully at the moment and in the back of my mind there’s a voice saying ‘don’t dick around with things that functioning as they should.’ I’ll probably stick with the Trispark and enjoy continued reliable ignition. With the Trispark being dependent a charged battery I ditched the original, dodgy generator in favour of a new Alton unit. If any of the Vincent Illuminati are still with us they’ve just spat their Cognac out – all over their computer screen.

With the Alton in situ only the truly strident rivet-counters would recognise this as a modern generator.

The Alton 12-volt generator uses permanent magnets, like the old dynamo on my pushbike when I was a kid. In an automotive application it works a treat, maybe even too good. After a particularly spirited ride with a couple of chaps on modern sports tourers a few months ago, the battery gave out. It was suggested to me the Podtronics regulator could have been faulty (as they are apparently known to be) and at continued high speed riding, with the generator pumping a full 150 watts into the battery for over an hour, may have cooked the battery. That ride brings me to another topic – speed.

Once the bike was fully sorted, the next problem I found was the speedo to be faulty. As it turns out, the after-market, twin-leading shoe brakes were fowling the speedo drive. Repositioning the drive gear corrected the intermittent nature of the reading but the speed was extraordinarily high and I needed to recalibrate the speedo. To do that, I fitted a small GPS speedo. The GPS revealed: when the speedo was showing 70 mph, the GPS was showing 112 kph. And when the speedo was showing 90 mph, the GPS was showing 145 kph. I won’t go on out of fear of incriminating myself but you get the picture. The speedo was accurate, I was actually traveling at the speeds indicated by the 72 year-old speedo! On the 72 year-old motorcycle.

On a final note, the bike has a great hunger for rear tyres. It may be the modern compounds are too soft, or combine bike and rider is on the heavy side but, on average, I have been getting about 2,000 km per tyre, which is not very good.

So, there we have it, up to today. The major gripe I have now is oil leaks. The Vincent is like a recalcitrant puppy leaving puddles wherever it goes. There is a fix at hand but I won’t go into that just yet in case any of the Vincent Illuminati are still reading.

I’ll have that beer now.

I thought the speedo was reading on the high side. Calibration with a GPS proved not. I was actually going that fast!

The tank decal had to be replaced with a more authentic HRD item. At the same time, the tank was given a new coat of clear. This was the result.

The Vincent HRD explanation.

Phillip Vincent was undoubtedly a very talented individual. Some folk may have noticed the cantilever rear suspension fitted to my motorcycle. Vincent first came up with this design whilst still in school, no doubt sketching his future motorcycle design when he should have been paying attention to his teacher. By the time Vincent was 20 he had convinced his father to buy him a motorcycle company. Howard Raymond Davies was both a motorcycle builder and racer who could boast Isle of Man Senior and Junior TT race wins on his own machines. Vincent Snr purchased HRD in 1928 and, in a nod to the famous origins of the HRD marque, Vincent retained HRD on the motorcycles up until 1949 when they dropped the three-letter moniker for fear of being confused with that other famous V-twin: Harley Davidson aka HD.

Banner picture by Jeremy Hammer.