From about the time my adolescent hormones started to make themselves felt, I began to hear tales about Vincent motorcycles. Then, as now, my preference was for an Egli Vincent, which is the creation of Swiss motorcycle racer Fritz Egli, who, upon finding he had reached the upper handling limits of a standard Vincent frame, turned around and built his own, to which he fitted the famous Vincent 1000cc twin engine.

Egli’s frames are distinctive insofar as they have a massive, tubular backbone and no cradle. The engine hangs from the frame and in fact forms part of the frame in an engineering practise often referred to as a ‘stressed member.’

This is the machine we’re after – well, close anyway. The photographer is unknown.

It should come as no surprise that engines from the fastest, most expensive, most exclusive motorcycles on offer throughout the fifties are not exactly lying around gathering dust waiting for Egli Vincent fans to stub their toe on. Nope, they are as rare as rocking-horse poo. Luckily, I have a plan.

Triumph motorcycles are a passion that extends back to my teenage years because those same adolescent hormones that were bouncing about at the thought of a Vincent Black Shadow also had to compete against the Triumph Bonneville. I remember the first time I saw a gleaming gold Triumph Bonneville as clearly as if it was yesterday. It was in fact 1974 I was on holiday at the seaside town of Augusta, South-West, Western Australia. That Bonneville changed my life and I knew one day I would own one. In hindsight, I didn’t have to wait all that long, by the time I was 18 I had my first Triumph and a life-long relationship with the brand was commenced.

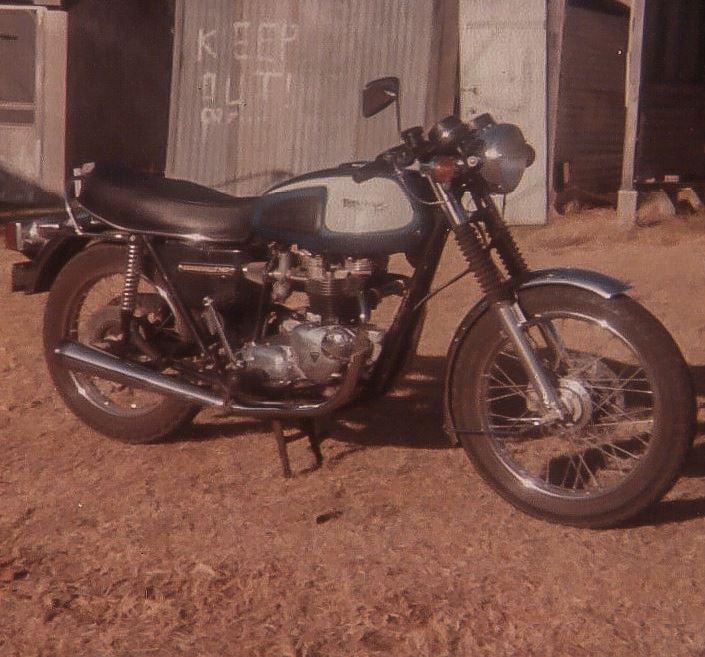

My first big, road-going motorcycle, a 1977 Triumph Bonneville 750 T140.

Naturally, my first Triumph was a Bonneville. I say ‘naturally’ because then, as now, the name Bonneville is synonymous with Triumph, for me there simply was no other choice. By the time I purchased my bike the venerable British twin had grown to 750 cc, had disc brakes front and rear but essentially, it was the same engine developed by Edward Turner some 40 years earlier in the form of the 500 cc ‘Speed Twin.’

At the time, unbeknown to me, Triumph had also built a 3-cylinder motorcycle. Such was my lust and determination to own a Bonneville, I was blind to the rest of the range, which is just as well because the Triumph Trident was way above my teenage, apprentice budget but destiny has a funny way of working things out.

Like most motorcyclists, my bike-radar goes off in all sorts of directions and the Egli Vincent has always been there. Last year I came very close to paying $5,000 to two pieces of Vincent crankcase from a 1955 1000cc V-twin. I was outbid at the last minute and immediately felt a wave of relief. Such is the value of classic Vincent machinery, I could have bought brand-new, freshly cast reproduced Vincent cases for about the same price, but they would be from this century, which kind of defeats the purpose.

Then, in a rush of blood to the head, I decided to build an Egli Trident. In the recent two or three decades Egli frames have been fitted with all manner of engines – even Triumph triples, although they are rare. In truth, a Trident engine will be faster, more reliable and sound better than a Vincent.

I started my research and a couple of frame makers started to emerge from the cyber jungle. They were Patrick Godet and Colin Taylor. Godet was in fact building complete, fully assembled Egli Vincents. Egli himself had endorsed the Godet machine that was made up completely from new parts. It is a modern motorcycle based upon a 70-year-old design, and it’s a thing of beauty. I wrote to both Patrick and Colin with my idea to build an Egli Trident. Colin wrote back. He was enthusiastic and helpful.

Sadly, Patrick Godet is no longer with us but his legacy will remain strong with many of his fine machines scattered around the globe.

Colin Taylor’s bread and butter is, of course, Egli Vincents but he’s willing to tackle anything. His enthusiasm was infectious and after receiving my deposit from across the equator, Colin got to work and the Egli Trident project swung into production. There was just one problem – I didn’t have an engine. Furthermore, you’re probably thinking, “what exactly is a Trident?” So, lets take a look at the British 3-cylinder engine that changed the world.

The heart of the BSA Rocket 3, the 750 cc, three cylinder engine designed by Triumph and built at BSA’s Small Heath factory in South-East Birmingham.

The Triumph/BSA 3-cylinder engine had been in planning and design for almost 9 years before its release. Triumph engineers Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele were the fathers of the triple. Singles and twins were common place in the British industry but there was a growing demand for faster and more powerful machines, particularly to feed the demand from America.

This presented a problem. The larger and more powerful twins became, the larger and more pronounced the vibration became. In hindsight, the progression from single to twin to triple seems logical, but it took Hopwood and Hele to bring it to fruition.

The Triumph prototype engine was completed in 1965 and the Trident could well have gone into production by 1966 but parent company BSA wanted part of the action. Not content with badge-engineering, BSA insisted on making a triple of their own and this is where things get a little ridiculous. The Triumph triple cylinder engine was built in the BSA factory at Small Heath, it was, for all intents and purposes a BSA engine. In following naming conventions of the day, engines destined for Triumph were stamped with the prefix T150. BSA engines were stamped A75. That’s easy, no problem there, except to see the difference between the engine prefixes one almost needs to get down on the ground to read the stampings.

It was decided the BSA engine would need a distinctive look so the barrels on the BSA unit were canted forward by 12 degrees, which (kind of) dissociate them from Triumph. The right side timing and gearbox outer cases were also altered to provide another individual touch to the BSA item. Think of designing something that is basically the same yet requires re-tooling, casting, machining etc and the simple act of making minor changes becomes a major undertaking. Luckily, the internals remained the same between the two engines, as did just about every other piece of the triple.

With the engine (almost) uniquely styled to BSA, it became apparent the Triumph duplex frame was would not support the forwarded slanting engine so the BSA would need a new frame too. Conveniently, Triumph would later use the same set up to allow inclusion of an electric start behind the barrels of their 1975 T160.

The finished product would add two years to the release of both bikes and BSA Triumph missed the opportunity to unleash the first mass-produced superbike onto the world market. Honda stole the show. The Brits had been caught resting upon their laurels. They were the motorcycle super-power of the time and probably expected to remain as such.

Triumph and BSA triples were winning production racing around the world, including the two most famous races of the time, the Isle of Man and Daytona. BSA dominated the American AMA competition well into the 70s but sales of the Japanese bikes sored, whilst sales of the British machines stagnated.

Possibilities are endless. This custom made bike uses a BSA Rocket 3 engine in a frame built by Les Whiston, of Rob North Triples, in the West Midlands, UK. The photograph supplied by the owner of the motorcycle, Mr Carl Cookson.

The bikes generally remained the proclivity of purists both then and now. With fewer bikes produced, BSAs command higher prices, which leaves Tridents as representing excellent value for money in classic motorcycling collecting.

In my search for a Trident, I uncovered a gem in the form of a ’71 Rocket 3. It is a basket-case but it’s all there and it’s the more appealable Mark I, American-styled BSA, rather than the boxy English design by David Ogle, who was more accustomed to designing radios, toasters and a thoroughly awful car. The Rocket is too valuable to separate its engine from the frame so it will become a project unto itself. https://motorshedcafe.com.au/rebuilding-the-rocket/

My ‘basket-case’ Rocket 3.

Elsewhere, in the same shed that I uncovered the Rocket, a few old Triumph Tridents rest gathering dust. One of those machines has been tagged as a donor to the Egli Trident Project.

Over the coming months and years, I will begin to bring the pile of dusty, rusty BSA parts back to life with my mantra of painting, plating or polishing every surface of the machine. Moving parts will be assessed and, if need, replaced. Likewise, the Egli Trident will also take shape. It wasn’t my intention to commence two projects but serendipity visited the Motor Shed so I’m basically committed to reviving a piece of British motorcycle history and creating something new, albeit with an engine from 1974.

Thankyou.

Certainly, be my guest.

Hi Dan…a month or 2 ago you were selling the egli frame and the dent…..did they go?

No, just had a change of direction with things. We’re back on track now.

Hi Dan,

How are you proceeding with the project? Are there any further photo’s you can post at present?

Hi Andrew, I haven’t done anything to this project since I returned home with the frame. I have been busy with the Norton restoration and I’m also writing a PhD thesis which has been consuming a lot of my time lately. Plus, I’ve picked up a paid $$ writing gig which also pulls me away from this site. I haven’t done anything on the Egli project lately, although I now have Mr Fritz Egli’s consent to use his name when referring to the project. I’ll do a story on that soon. Dan.

When Dan contacted me I was infected with his enthusiasm. I’ve lost count of the number of people who’ve contacted me asking if I knew where they could lay hands on a Vinny motor….

Also, I too, didn’t have a Trident motor lying around….one was needed to build the frame around!

However, in the frozen North of the globe in Oslo, Norway, I’ve a friend with more than a passion for Rocket-3s and Tridents.

He’s a Rob North triple fanatic (suffice to say he’s really hard core…..anyone who has so many of the bikes that he’s run out of space in his own house, garages and workshop that he even has 3-complete ones in the lounge of his mother’s house !

Well, there was nothing for it but for me to grab a flight with my trusty welding kit and appropriate 4130 tubes in my hold luggage to Oslo !

Of course my friend had numerous engines available as well as, just about, enough space for me to swing a cat in the fabrication shop !

The frame was all prepared and working with the slave engine and drawings from a very good engineer friend ( who has 2- Egli-Vincents made by him using my frames and an Egli-Trident plus numerous other masterpieces) within a few days in wonderful Oslo (really worth visiting) I was able to carry everything back to my Italian workshop, finish the frame, make the swing-arm (to the Swiss drawings) and get the whole lot to my electroplate shop.

I’m more than fortunate to be allowed to “do” the pre-polishing and stand by the plating vats while my products are finished.

I’m seeing Dan later this year to present him with the result.

Watch this space !

Thanks Colin, very much looking forward to bringing that frame back home.

Great article never knew much about the history of the rocket am very impressed and hope the follow ups on its growth continue.

Thanks Lex. Happy to enlighten you.