Recently we tracked down a stunning example of an Egli Vincent and, for your author, there was a special treat in store.

In Part I of the Egli Trident project, we touched upon the exclusivity of the original Egli Vincent motorcycles and the growing market for replicas and tributes to the brand. Similar to the prevalence of reproduced Norton Featherbed frames, as used on the Motor Shed Triton, Egli frames are being produced by specialist, and some not so special, frame manufactures around the world, such as Colin Taylor who fits firmly into the former group and is building the frame for my Trident. This is just as well because Mr Fritz Egli is no longer producing Vincent-powered motorcycles. Egli has chased the horsepower and has found the Yamaha 1300 engine ideal for his current creations.

Until recently, I had never laid my eyes on an actual Egli Vincent motorcycle, or any Egli machine for that matter so I reached out to John Lagdon, an acquaintance who I knew only through mutual friends. We set up a meeting to allow me to view John’s Egli and spend some time learning more about the Egli setup. In the back of my mind I was secretly hoping John would permit me to sit on the motorcycle to make sure my 6’ 3” body wasn’t too tall for such a bike. My Triton is a bit of a stretch so I’ve been hoping the Egli might be a little more forgiving, although it’s probably moot as by this stage my frame has been paid for, manufactured and electroplated.

Arriving at John’s house, I was met by a tall, lanky man of about the same height and build as me. Instant relief. We walked through the house out to the garage and there it was: the Egli was sitting at the edge of the garage, gleaming in the mottled sun, the big engine hanging bellow a polished aluminium fuel tank, it is indeed a thing of beauty, but it hasn’t always been like this.

John Lagdn’s Egli Vincent is indeed a thing of beauty. Photograph by John Lagdon.

John found his Vincent in a motorcycle dealership in Cincinnati, Ohio, in around 1985. It was part of a collection of racing machines Domiracer Motorcycles obtained from former racer Ed LaBelle. LaBelle was a three time Canadian road race champion and an accomplished drag racer and it was from the drag racing stock that John secured the beginnings of his project. Evidently the bike was a survivor from the heady days of US/Canadian 1960s drag racing. The engine cases still bear the scars of a drop too much methanol, which I feel add to the history and mystique of the bike, although one can share the heartache of the thrown primary drive chain as it smashed its way out of its enclosure all those years ago.

John discovered the ex Ed LaBelle Vincent drag bike at Domiracer Motorcycles in Cincinnati, Ohio. Photograph by John Lagdon.

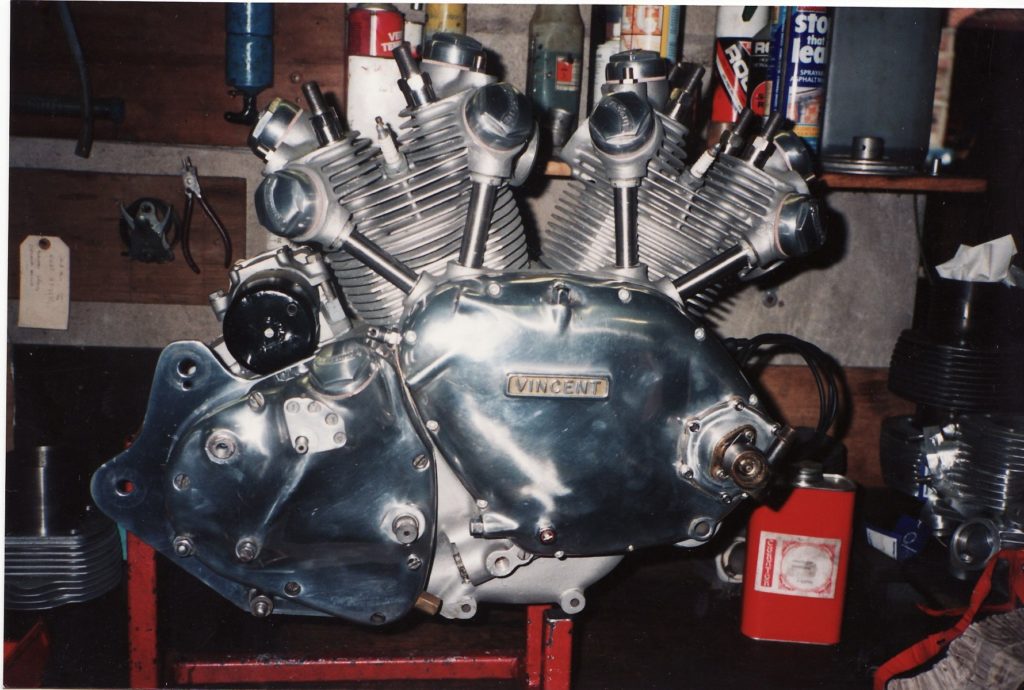

It would take a move from the UK to Australia and some 19 years before John got to license his Egli Vincent. There is insufficient space here to go into the trials and tribulations John went through in getting his bike from a project to a functional motorcycle. A lot of the grief suffered by John started even before his frame arrived in Australia. It took an extraordinary long time to complete the frame culminating in John having to, let’s say, get persuasive with the builder. When the frame eventually arrived it was out of true and the nickel plating well below par. A defining feature of an Egli build is a nickel plated frame so I can appreciate his frustrations at something less than perfect. Nevertheless, through determination and perseverance John’s creation was born and the La Belle engine was given a new lease of life on the roads of Perth, Western Australia. Aside from the engine, very little of La Belle’s bike was used in the build, but that’s the thing – there is very little to an Egli Vincent. It’s all engine, a big, stonking, lump of alloy and power that takes that takes centre stage. In a classic case of ‘less is more’ the Egli boasts simplicity and function.

A rare photograph of Ed LaBelle astride his Vincent racer. Photograph supplied by John Lagdon.

Egli motorcycles have a large diameter steel tube that runs from the head-stock to the seat base. The engine hangs from that tube, secured at the top of each head and at the point where the swing-arm pivots, the combine effect being the engine adds to the rigidity of the design in what is termed a ‘stressed member.’ It is simple, functional and highly effective. In another tilt to functionality, the main tube doubles as an oil tank.

The engine on the Trident will sit slightly in front of the swing-arm pivot, secured in place by plates that bolt to both frame and engine. Colin explains, “the Egli-Tri swing-arm is different because of the way it picks-up on plates where, as you rightly say, with the Vincent, it mimics the standard Irving designed location plate which sits between the G1 kicker cover and the drive exit of the engine on the right-hand side of the engine and the boss on the back of the Vinnie’s crankcase. Another one of the significant differences being that the triple’s swing-arm is fabricated from round tubes, where the Eg-Vin ones are made from round pivot tube (mimicking the standard Vin’s design) with flat-sided oval tube legs.” Lesson over, back to John’s bike.

John was happy for me to try the bike out for size and, must have been satisfied I knew my way around a motorcycle because he said “Do you want to take it for a ride?” This is the kind of invitation that rarely comes around and despite not having any protective gear it was not one I was going to decline. As cool as a cucumber I said, “Yeah, sure.” Deep inside I was feeling equal parts happy dance and a gut-churning anxiety. My anxiousness was made worse when John said, “Please don’t drop it.” I hadn’t even thought about that! Crikey, this bloke hardly knows me and he’s letting me loose on his Egli Vincent.

John’s Egli Vincent under construction in Perth, Western Australia. Photograph by John Lagdon.

My Egli Trident under construction in Norway. Note the signature 12 cm tube that acts as a backbone on both machines. Fristz Egli’s frame was introduced in 1967 and is still being produced to this day. Photograph by Colin Taylor.

The beast was fired up. Not one for mufflers, John clearly loves the sound of his Vincent. The straight through pipes resemble mufflers, but, don’t be fooled, they don’t muffle a thing. The bark bounced of all the walls in the laneway of what must be a very tolerant neighbourhood.

With a reasonably complicated start-up procedure, the last thing I wanted to do was stall the engine or otherwise let it stop so I idled down the lane blipping the throttle. Enjoying the bark and finding my way around the bike. Once I was satisfied everything was there, brakes, gears, throttle – that sort of thing – I ventured onto the road, and travelled straight across it, oops that turning circle is a bit wide. I paddled the bike backwards and then had another go at riding off.

The heart of the beast, the Vincent 50 degree V-Twin engine was the fastest thing money could buy when introduced in 1946. Photograph by John Lagdon.

This time I sort of got going. The gear change, although still on the right side, was directly opposite in movement from my Triumphs so I muffed the first few changes and forward progress was stilted for the first couple intersections until I got the hang of things. Interestingly, Vincents have a gear indicator on the side of the gearbox but I wasn’t about to look down to see what gear I was in, my eyes were planted firmly on the road ahead.

Some say Vincent engines only fire at every second lamp-post but this thing hammered. In the few brief opportunities I had to let the Vincent off the leash I got it, I understood the magic. It pulled hard and gave me a glimpse into the world of the Vincent. I would have loved to explore the upper limits of the engine but not as long as it belongs to someone else, additionally suburbia intervened and I was frequently calling on the massive front, 8 leading shoe arrangement to slow the beast. The rear brake had been lifted from a BSA and was the same as the one on my Triton so I was aware that was pretty useless. But, I’m happy to report, didn’t crash or drop the bike.

Idling back into John’s laneway I felt relief at having successfully navigated a few suburban streets on the most valuable motorcycle I had ever ridden. The bike was comfortable enough and nimble beyond the bulky appearance, sufficient to let me know I had made a good choice in opting for an Egli setup for the Trident. It was also sufficient to let me know I must one day build an Egli Vincent.

The author about to experience a special treat – my first ride on an Egli Vincent.

I’ll put it down to being a Typo error….the Eg top tube/oil tanks are 100mm diameter, not 12cm.

Pleased that you’ve ridden an example of an Egli…for you, the best has yet to come.

As for the sounds….well, yes, the V twin Stevenage engine does produce a unique sound but the yowl of a Trident (or Rocket 3) when exhausted via a 3:1 system really is special music.