Tales from the Shed: let down by a ten-cent seal

This piece has been written by me for inclusion in Classic Vibrations, the magazine of the Indian Harley Club of Bunbury, Western Australia.

Newton’s third law states for every action in nature there is an equal and opposite reaction in force. Let’s look at that. A piston, for example, converts chemical energy to kinetic energy and through a series of mechanical interactions transfers that energy to the road where it propels the operator forward. For the kinetic energy to get to the road, there is a multitude of equal and opposite reactions that are mostly protesting and working against forward momentum. These mechanical devices, for the purposes of this communication let’s call them motorcycles, have reached incredible levels of sophistication and reliability yet some of us, in fact most folk reading this I suspect, have an unusual attraction to motorcycles from the last century.

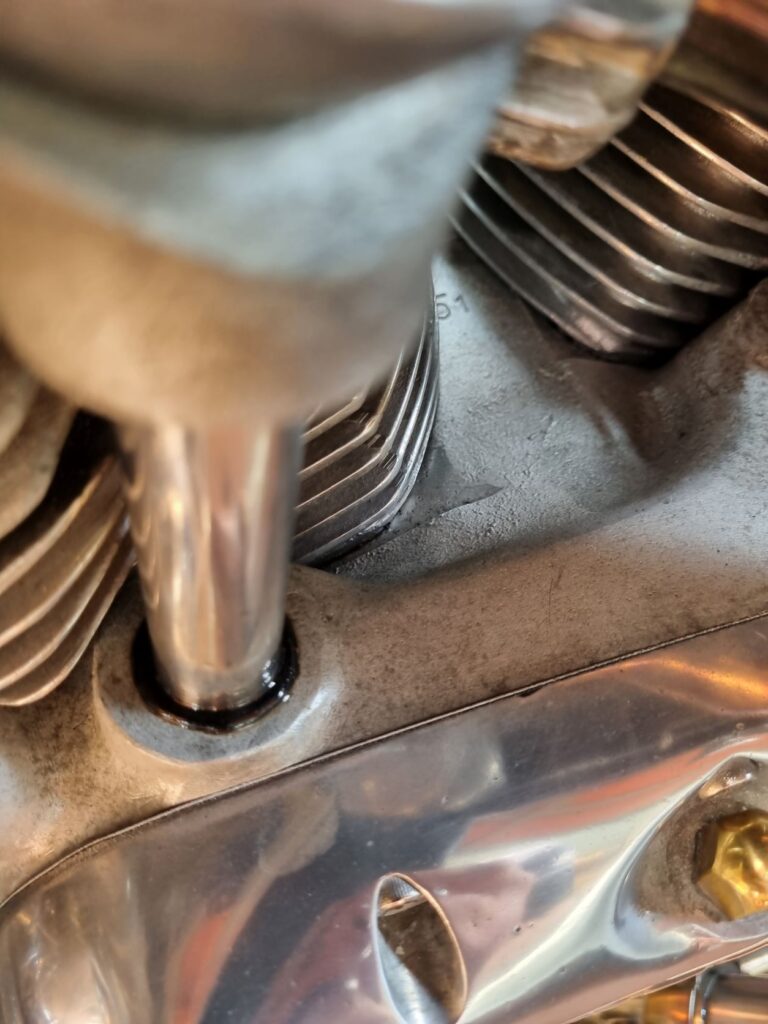

It looks innocuous enough, but this small trickle soon turned into an oily torrent.

We have a love for classical machinery that requires a deft ability on behalf of the operator to continue converting energy to forward propulsion in a variety of challenging conditions. For me, whilst I am cruising happily along on my classic motorcycle the world is a beautiful place. My machine is a valuable and prized example of the second industrial revolution. However, when that machine fails, it can quickly become a cantankerous and unreliable old bike. As happened recently.

I had been very much looking forward to the Australia Day run out of Boyanup. Being a combine event, I was equally looking forward to bringing my classic Mustang as well as my Vincent so some juggling of vehicles between home and Boyanup was required. Just to back-track slightly, on the Sunday before Australia Day I rode the Vincent to Mandurah to meet up with the Mob up there and joined them on a coffee run up into the hills. I have been aware for some time a pushrod seal on the Vincent were seeping oil and I have attempted makeshift repairs by wicking silicon into the aging seal and round the tube. But the equal and opposite forces could not be kept at bay and by the time we arrived at Dwellingup I was leaving embarrassing amounts of oil wherever I parked. I was 100 miles from home so both a clean-up and top-up were in order. Arriving home, I wicked more silicon into the offending seals in the hope I could stem the flow and make the Australia Day ride few days later. Alas, I couldn’t.

To get to the seal, the push rod tubes must be removed. To get to the push rod tubes the heads must be removed. To get to the heads the upper frame member must be removed ….

By the time I arrived in Boyanup on the Wednesday before Australia Day the Vincent had a coat of oil down the right side. Oil was migrating to the rear tyre so the machine was parked up and my Australia Day was thereafter confined to four-wheels. Sure, I have other bikes but my bottom lip was well and truly on the ground and I was not prepared to countenance another machine.

In the days following the ride, I licked my psychological wounds and retrieved the bike. The IHC Two Day Rally is fast approaching and I cannot ride the Vincent in the event in its current state so I had to get straight into it. I had contemplated handing the machine over to someone a little more skilled in Vincents than I but I was assured taking the heads of a Vinnie is no more difficult to those on my Triumphs or Ariels, so I dived in.

The offending seals are about the same size as a wedding ring. A ten-cent band of rubber that is easily popped out by the fingers once the pushrod tube is removed. The problem arises in removing the pushrod tubes for, to do that, the heads must be removed and, to do that, the front half of the frame must also be removed. It’s a massive job to get to four dinky little seals.

With the fuel tank off, the upper frame member is clearly visible. This needs to be removed, along with the front end to allow one to remove the heads.

I have mentioned a frame, but Vincents don’t have a frame in the normal sense of the motorcycle world. They have an upper frame member which bolts to the top of the engine and carries the girdraulic front forks, and a rear frame member which is basically a triangulated swingarm that holds the rear wheel and is bolted to the rear of the engine. The engine is essentially part of the frame: everything hangs off the engine.

This is it, a lot of work to get to the offending seal.

Things get a bit tricky removing the upper frame member because carburetors, electrics and cables all need to be removed or otherwise taken care of. Cleverly (or infuriatingly if one has to remove it) the upper frame member is also the oil tank so that has to be drained too. I must say, I found the dismantling the machine an enjoyable few hours in the shed. Sure, the neighbours heard the odd swear word but, by and large, things went quite smoothly. As the sun was dipping into the Indian Ocean just across the park, I rewarded myself with a couple of stubbies of Victoria Bitter. Sitting there, sipping one of Australia’s finest ales, I reflected on the beauty of the Vincent design.

The push rod tube. The top part is secured into the head by the gland nut, whereas the lower section simply pokes through the seal.

The synchronicity from the front wheel, through the engine to the rear of the machine almost punches you in the face (or perhaps that’s the VB). If we can go all Newtonian again, Phil Irving, the designer of the Vincent engine, knew exactly where the forces of mechanical design would work, and where they would fail. Now that I have the motorcycle apart, I can see his thesis laid out before me and it is brilliant. Let down in this case by a 10 cent rubber seal which bears a quite unequal relationship with the energy inherent in a 1000cc V-twin engine.

And now we wait for parts to arrive ex-East.