This is a retrospective look at a project that was started in 1989 and finished about 25 years later. The reasons for the extended rebuild, well two rebuilds actually, are recounted in the book simply titled “Rebuilding the Ariel” and available on this site in eBook format. This story is an excerpt from the book.

I still vividly remember my first ride on the Ariel. It hadn’t been in our family for very long and Dad was quite pleased with having found such a good example of the iconic 1940’s sports bike. The Ariel was like nothing I had ridden ever before. Even before you start riding, the bike lets you know it’s different. The broad saddle, ‘tear-drop’ chromed and painted fuel tank with big rubber pads for the knees to prop against, bulbous front guard, an odd-looking instrument panel in the centre of the fuel tank are just some of the antiquities associated the motorcycle. Bakerlite switch-gear and an abundance of chrome-plating also let me know this motorcycle was different from the modern machines I was familiar with.

It was 1989 and the Red Hunter was the first “vintage” bike that I ever rode. In strict terms, the bike is not actually a vintage machine, it would need to be manufactured before 1931 to be deemed a proper vintage bike, but it certainly looked like one to me.

The 1951, 500 cc Red Hunter had plenty of power but the front end floated about like it was semi-detached from the rest of the motorcycle. The rear end was equally disjointed and, with the suspension beneath the saddle, the whole thing was a jaunty, wobbly and scary experience. I came away from that ride feeling the machine was confrontational. It had challenged what up until that time I believed motorcycling was all about. For me, motorcycle riding has an almost infinite range of variables between slow and easy right up to fast and exhilarating, with a whole lot in between. Riding something that was slow and exhilarating was completely new.

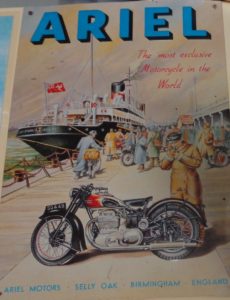

Make no mistake, these things were sports bikes for my father’s generation, they were the ‘Fireblades’ of their day. The Ariel was an affordable motorcycle that looked resplendent in bright red and sparkling chrome.

I recall thinking after my first dalliance with vintage motorcycling that it was an extreme sport for pensioners. They take their life into their own hands on many of the old bikes that often go like stink but handle like a sack of spuds and have little or no brakes. I’ve softened that view over the years as, although I’m a long way from drawing a pension, I’m increasingly enjoying being perched on top of old motorcycles.

The Ariel was taking its place amongst Dad’s collection of motorcycles that included BSA, BMW and Kawasaki machines. It was by far the most handsome and exclusive bike in the shed. Pretty soon after I set eyes on the Ariel, Dad said, “take her for a ride.” He didn’t say that very often so I jumped at the opportunity.

The bike was propped up on its rear stand. The stand itself is quite a sturdy piece of equipment that hoists the entire rear end up off the floor. In this position, one can safely sit on the bike with it upright and basically fiddle with it, which is exactly where I was when the instruction to take it out was offered. I started dabbing at the kick-starter, pushing the big long stroke 500 through its axis a couple of times, not expecting anything much to happen.

Clearly there was fuel in the tank, I knew that because it was seeping out of the fuel-cock, running down the line and dripping onto the magneto – which is a recipe for disaster and would need some attention in due course, but for now we’re off for a ride, just as soon as I can get this thing started.

International appeal! In a country famous for the re-creation of the English Royal Enfield motorcycles, Harjit Singh Dhanjal, of Calcutta, India, enjoys getting out and about on his Ariel Red Hunter.

I rose up on the kick-starter and gave it a stomp. At least that was the intention but, you don’t stomp on the kick-starter of a big British four-stroke single. You may stomp on a two-stroke, such as I was familiar with at the time, but the kick-start on a big single works best when its allowed to swing through its access in its own good time. As the kicker goes down, the engine draws breath, a big long gulp of air that passes through an ancient carburettor which, for the most part, seems to do a good job of shooting petrol in the general direction of the inlet manifold.

Ariel leathers worn by John Hancox, of Hancox Art, during his exploits racing single-cylinder Ariel motorcycles.

Anyone familiar with a good choke-hold around the neck (and, let’s face it, who isn’t?) would recognise that awful sucking, gurgling sound one makes attempting to draw what is seemingly one’s last breath. Similarly, in the case of the Ariel, the engine sounds like it is sucking and choking at the same time, then, all things being equal, a good rush of air and petrol vapour breathes into life into the big engine and a smoky, vibrating, chug-a-lugging has the whole bike dancing about even before a gear is engaged. It’s a strangely satisfying sound.

Over the years I became intimately familiar with the starting routine required to get the Ariel going in about one or two kicks. Usually, if the bike wouldn’t start on the third kick I would know something was wrong and commence an investigation. For now, I had the big 500 single rumbling away beneath me, a new appreciation for the internal combustion engine was building with the confidence that came from each explosion in the upper reaches of the cylinder block. I reckon I could count each one of those explosions. Twisting the throttle produced a healthy build-up of revs and an audible induction roar coming from the open Amal carb.

To get moving I had to stand up, feet planted firmly on the ground, and push the bike off the stand. In rolling the bike off the stand, the wide, tractor-seat styled saddle whacked into the back of my legs, plonking me back down in the saddle at roughly the same time the bike rolled to a stop. I dabbed and waddled the ungainly machine out of the shed (in hindsight, I believe I was the ungainly element).

If I felt clumsy and was sure it would look worse from where Dad was observing me, I feared he might change his mind about sending me off on his most recent acquisition so I figured I had better get out of there. I found the right-side gear change and pushed it down into first. Wrong. First gear is engaged by pulling the lever up. Fortunately I was on a bit of a hill so, combined with the long-stroking, lazy engine, it didn’t matter too much that I had selected second gear. A bit of a chug-a-lug and I was away, searching again for that right-side gear change.

Younger readers right now may be asking themselves “what’s a right-side gear change all about?” Back in the day, all bikes were right-hand change, then for reasons not clearly understood by the occidental world, the Japanese first came up with a left-hand gear shift and everyone else followed suit. Britain and Europe were happily producing the right-side gear change, whilst the US insisted on changing gear by hand, then, one-by-one, the various manufactures converted to the left.

Not exactly a Red Hunter, this custom Ariel was photographed on the Isle of Man in 2018 and is reproduced here simply to celebrate the sheer beauty of the creation.

The Ariel gearbox engaged with a rather sure clunk, and I gathered speed. “Clunk” is a great word and very descriptive of the Ariel gearbox. A solid construction of alloy and steel, the Ariel box is the same size as that found in a small, modern-day car. Whereas modern bikes tend to change with a ‘click,’ the Ariel always clunks into gear. Up into first – clunk, down into second – clunk, down again for third – clunk. Later, I would continue to use the clunk, clunk, method of moving between the gears then occasionally, in moments of panic, I would smash my way back up through the cogs in an attempt to wash speed off as the brakes were quite dreadful, but for now, back to that first ride.

The steering on the old bike was quite dreadful as the handlebars seemed to flop from side to side at will. Unbeknown to me there was a solution right at hand, in the form of a large bakerlite knob at the top of the triple clamps. The device is a damper that is used to literally tighten the steering. This is a useful device which is let down by the obvious flaw in so much as a rider has to remove one hand from the bars to reach across and tweak the knob. Even if I had been aware of the damping capabilities available at the steering head on this ride there was no way I was going release my white-knuckle grip on both ends of the handlebar.

Fast and affordable, the Ariel was the Fireblade of it’s day. Bolt Blyth has been racing his Ariel 500 for over 10 years with great success. We’ll be doing another piece on this race bike in the near future. Photograph courtesy of Bolt.

The farm-house sits on the side of a hill. It has a long gravel driveway that leads down past some sheds and onto the bitumen of the South West Highway. The drive-way intersects at the sheds and goes off to some cattle yards and shearer’s quarters. Very soon after leaving the home shed I noticed the strange handling characteristics the old bike seemed to possess. I also noticed the lack of brakes and that I had very quickly gathered some speed on the relatively steep gravel descent. During my youth I had frequently negotiated these roads at great speed – often sideways – on my motocross bikes but on this occasion I wasn’t feeling at all comfortable about the ride.

As I came upon the sheds, I opted to ride down towards the cattle yards because, up until that point, I had been going downhill and the route to the cattle yards flattened things out a bit, which seemed like the safer option. At the end of the road there was a turning cycle large enough to swing an articulated cattle truck around. Clearly, I was going to need every available inch of that circle as I was still coming to grips with the odd steering, suspension and poor brakes. The throttle cable was sticky and the brakes hardly worked but I managed to pull the monster up enough to make the turn and head back up the hill.

I was quietly relieved to ride the bike back into the shed and park it up, safe in the custody of Dad. I had ridden the Ariel one, perhaps one and a half kilometres that day. I was safe, the bike was intact, everything is okay, cool. Maybe it wasn’t that bad after all.

Readers might be happy to learn Ariel are up and running again as a low-volume manufacture. Using a 175 bhp, 1250 cc Honda V-4 engine, the Ariel Ace presents an aggressive stance with the promise of an exciting ride. Picture courtesy Ariel Motor Company.