This is the third instalment from “Rebuilding the Ariel,” available on this site in eBook format.

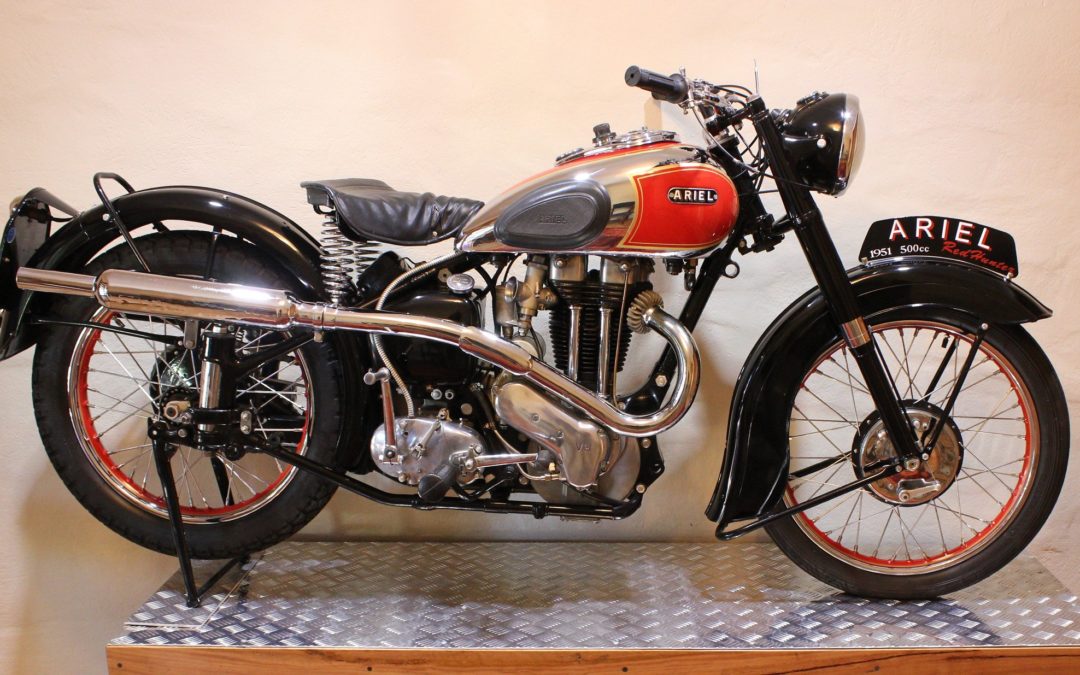

When Dad told me he had purchased an Ariel I was unaware he had owned one as a teenager. To be honest, I wasn’t all that familiar with the brand and had to do some research to learn more about the Red Hunter. There was no google back in those days, I had to learn the old fashioned may, with books and tuition. The tuition came via friends and acquaintances and it was from one of these latter sources I learned Dad used to own a Red Hunter when he first hit the streets – legally that is. I also learned the bike was considered a spirited performer and, by all accounts, a handsome machine. Sadly, Dad’s purchase wasn’t such a great example in terms of presentation but she ran okay and performed admirably for a vintage motorcycle.

The 40 year old machine had at some stage undergone a restoration but it was in need of a lot of work to bring it back to pristine condition. For example, just casting an eye over the bike revealed the ‘Ariel’ tank badges held in place by epoxy-resin glue, the engine wasn’t all that oil-tight, the chrome plating was blemished and rusty, as was much of the tin-wear. Most of that work was going to have to wait a while. My father was never one for aesthetics and he was quite content to leave the bike as is.

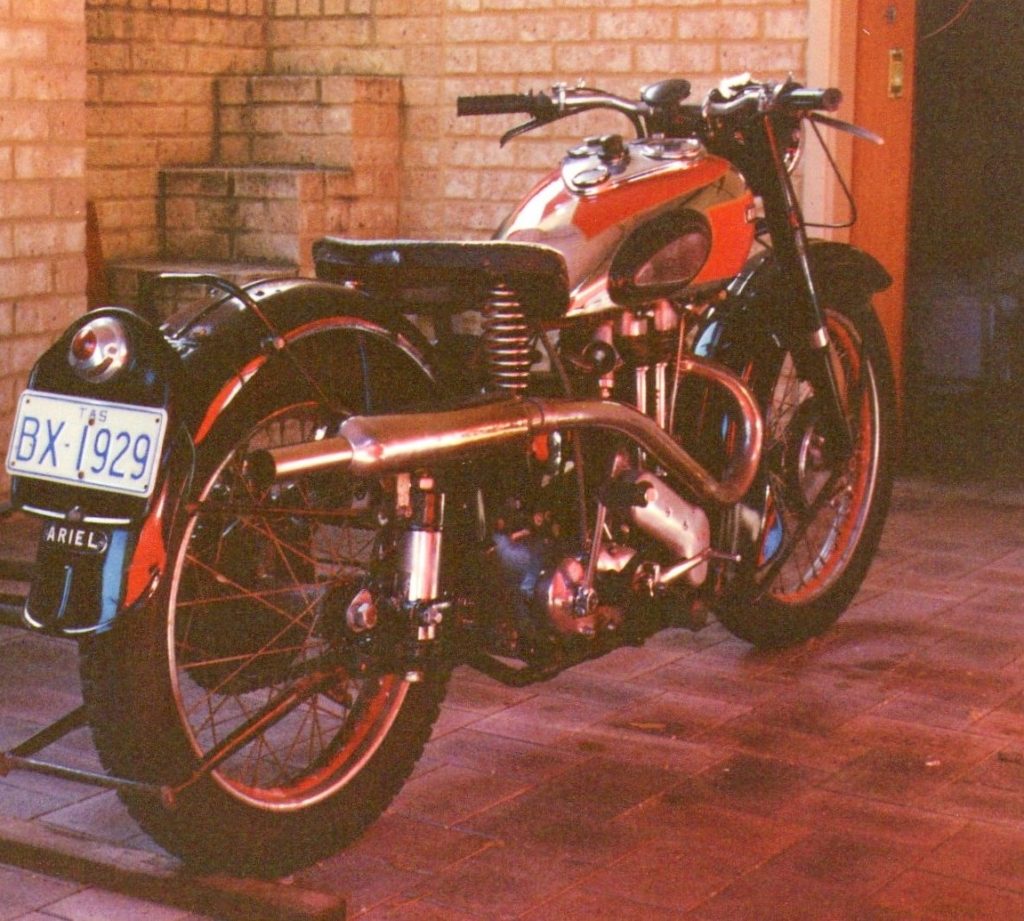

Dad was not that big on riding his vintage machinery so seldom felt the need to licence a bike immediately upon receipt. If a bike was licensed it generally stayed that way. The Ariel arrived bearing a Tasmanian registration plate, which was good enough for Dad, by the time the registration would run out he’d have enough of the bike anyway. Additionally, there are some fairly quiet country roads and lane ways around the farm where aging bikes, and riders, can be taken for a spin.

Having said that, to my knowledge, whilst the Ariel was in Dad’s shed, it was rarely ridden beyond the driveway of the farm, probably because the driveway is over one kilometre long and by the time you got to the end of it on the ancient machine, frazzled nerves meant one was usually ready to turn around and ride back to the shed. I might add the driveway is gravel, usually corrugated, potholed and dusty. As a teenager it caused no end of consternation to finish a polishing job on my latest pride and joy only to have it look like a trail bike by the time I made it to the bitumen.

The Ariel was a bit rough when it arrived from Tasmania but it ran well and came up alright with a bit of wax and elbow grease.

Aside from the trials and tribulations I have already attributed to the Ariel, once I got over the hinginess of the frame and lack of brakes, I actually learned to love riding it, I still do. That big, old, long-stroke 500 cc piston chugging and shaking beneath the fuel tank (itself vibrating about on its mounts), the induction noise pop-pop of exhaust all add up to a wonderful experience. Once underway, with the timing set to a suitably advanced position, the bike was a joy. I recall back in the early days of riding the Ariel when I finally realised why the big British singles were referred to as “one-lung” bikes. The engine acted as a bellows that sucked air in and coughed it out. Roaring down the road, the big single almost took on the biological aspect of the lungs from some large beast.

At this stage it is evident that I did get beyond the bottom of our driveway. I can’t recall how many rides I took the bike on whilst it was still bearing the old Tasmanian registration but eventually that ran out and Dad chose not to take out Western Australia registration. By that time, having been a bit of a ‘farm-hack,’ the bike would have needed a fair amount of work before it would pass examination so that was going to have to wait. The Ariel mainly sat in the shed as Dad focused his attention towards some of his other many and varied pursuits.

For a long time the Ariel seldom turned a wheel and only received attention during one of my infrequent visits to the farm. As it transpired, the responsibility to get the machine up to roadworthy standard would be vested in me.

Our weekends.

Looking back, it actually took a great deal of work to bring the machine up to club licence specifications. Back in those days, raising children and a hefty mortgage meant finances were tight. In motorcycling it is pointless, and in some cases dangerous, to cut corners. This would see me scrimping and saving money to be tipped into the project. The result was well worth the effort and by the time the machine was roadworthy I knew my way around it very well, but it did take a while to accomplish.

At this point, I should explain the Ariel was restored twice by me and at least once by someone else. My first restoration was purely mechanical, mainly to get the bike roadworthy and ready for concessional licensing, chrome and paint would have to wait until I could afford full rebuild – some 20 years later. The rebuilds had quite different objectives, which will become evident in the chapters which follow (recall this is an excerpt from the book Rebuilding the Ariel).

When the Ariel arrived I was living and working in Esperance on the South-Coast of Western Australia, some 650 kilometres from the farm. Back then, we would get up to the metropolitan two or three times a year, which usually included at least one visit to the farm.

Generally, soon after arriving at the farm, I would wander out to the shed and begin tending to one, or more, of Dad’s bikes. Working alongside Dad in his shed was a good way to converse. Never one to sit and have a chat, Dad was more at home with banter about the machinery that occupied his spare time. Frequently he would demand to know what I was doing about the latest high-profile homicide or whatever crime was being reported in the media, between welding strokes of his latest project.

I usually finished off the maintenance with a good polish followed by a ride.

My favourite bike in Dad’s collection was undoubtedly the Thunderbird. Dad finally managed to secure the 650 Triumph a few years after the Ariel. It was a particularly nice example of a 1956 machine that is, by all accounts, rather rare. The Thunderbird is fitted with an English SU carburettor and finished in all-over silver, including the frame, which I was told indicates it was an export destined for Australia, although I have since discovered that to be false.

Ariel bobber photographed at Peel, Isle of Man, during TT week in 2018. Note the front disc brake – we dream of such things for the Motor Shed Ariel.

Despite what was apparently a fine restoration, the Thunderbird regularly needed some tweaking to keep it in order, not the least of which was the odd dribble of oil. Anyone who has ever owned an old British bike, and a good many folk who haven’t, will testify to their capacity to spill their guts from orifices designed to contain lubricant rather than give it liberty. The Ariel was particularly bad for this, therefore maintenance always started with a degrease to get rid of all the oil and built up gravel dust. After I got the Ariel cleaned up I would turn my attention to the Thunderbird.

Artist and dedicated Ariel enthusiast John Hancox leathers display the Ariel logo and hang proudly in his gallery on The Promenade in Douglas, Isle of Man.

The Thunderbird had been lovingly restored by a member of the Vintage Motorcycle Club in Perth. At the time the bike was restored I was in fact a member of that club but there was over 450 members so I was unable to place him. Sadly, the gentleman who restored the bike never got to fully enjoy it as he passed away soon after completing the restoration, receiving “the big chequered flag in the sky,” as the club used to so eloquently put it whenever they lost a member.

The bike was subsequently acquired by an ex-patriot Englishman who very soon thereafter decided he would migrate back to the Old Country. He loaded all his goods and chattels into a container and shipped it all back to the UK. He then gathered up his family and, similarly, shipped them all off ‘home.’ Evidently things didn’t go as well as expected. Upon arriving in England, the gentleman decided things weren’t that bad in Australia after-all and resolved to return. They actually left the UK before the container arrived, and returned to Perth. It took another two years before the container was turned around and arrived back in Western Australia, whereupon the Thunderbird was removed and promptly sold – to Dad.

If this excerpt has wet your appetite, Rebuilding the Ariel can now be purchased online in eBook format right here!