Every time I put my foot down hard at under 40 mph in this muscled Mustang, it sounded like ten vestal virgins being raped simultaneously. Actually it was only the tyres (Bryan Hanrahan, Modern Motor, 1966).

The things you could say in 1966! We’ll get back to Bryan later, for now the Mustang has taken another great leap: we’re on the road. The car has passed engineering with WA Department of Transport (DoT) approval for a modified “high performance” engine, rack and pinion steering, coil-over suspension, improved brakes et al. In other words, she’s totally legal and licensed to thrill.

Aside from the restoration, dealing with and meeting the expectations of the DoT has been tiresome. At the end of this piece is a list of the requirements I had to meet before the car would be considered roadworthy. It should be noted, all of this was because I fitted improved braking, steering and suspension. The components I used had been previously been engineered and deemed compliant with Australian Vehicle Standards Rules. A gazetted engineer had to examine and sign off on all the items on the list. He spent the best part of a full day with me and the car, which included taking it to a workshop equipped with a dynometer to ensure I wasn’t producing too much horsepower. Had I rebuilt and licensed the car in its original form, none of this would be required.

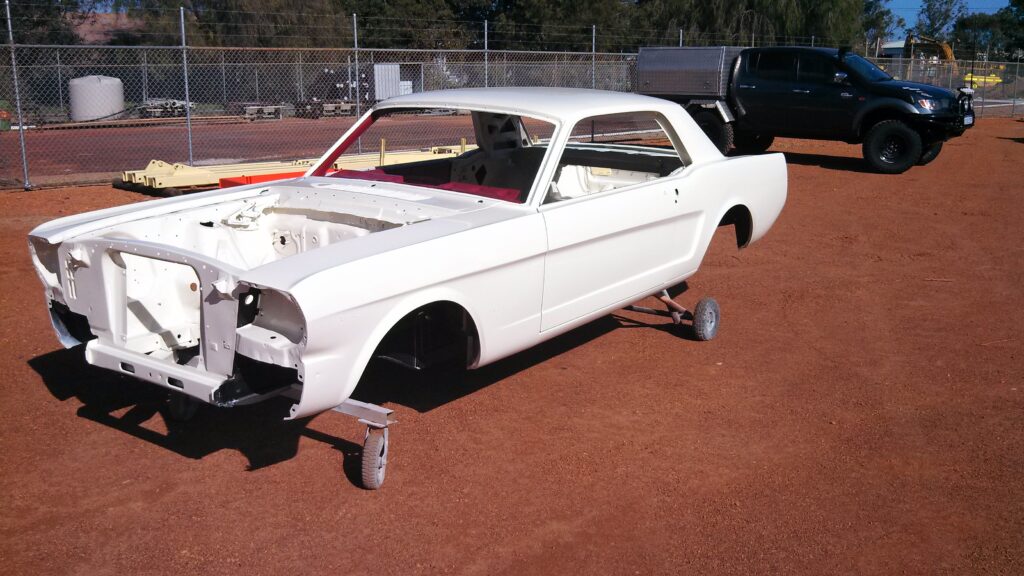

The DoT movement permit has a provision for a number plate. I used “THESEUS.” The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that raises the question of whether an object that has had all of its components replaced remains fundamentally the same object. Such was the state of the original body, everything in this photograph, save the roof, has been replaced.

What started as a transmission rebuild eight years ago grew to a full nut and bolt, rotisserie restoration. Every skerrick of paint and filler was blasted away revealing a very sorry sight, but that’s all history now and the scars of financial pain have diminished. What I ended up with was essentially a brand-new body, with more than half the panels replaced.

The modifications I have carried out on my car probably put it into the ‘restomod’ category of rebuilds. I’m not all that comfortable with the term ‘restomod.’ It’s a contraction of restoration and modification and came out of America where the modifications I’ve made are more readily accepted. In my case it is probably an apt description but I prefer to say ‘make it your own.’ That’s what I’ve done, I wanted to retain the original feel of the Mustang whilst making it safer and more pleasant to drive, and I believe I’ve achieved that. The car tracks beautifully and gives me great satisfaction knowing I’m (kind of) responsible for that.

Recall from the early days, when I said, “One of the defining features of Falcons of the sixties and seventies is the feel of the steering. It was much better than the equivalent offered by Holden and Chrysler but my Mustang was simply awful to steer. Added to this, the transmission was slack and spongy. The car was very much a disappointment.” Well not anymore. One of the reasons the car handled so poorly was the thoroughly agricultural conversion carried out by Ford Australia (Homebush story) way back in 1966. In his 1966 review of the Mustang, Bryan Hanrahan said, “I liked the Mustang. It made me feel ten years younger when I first drove it: it took ten years off my life the first time I tried to corner it hard.” Ironically, original Australian-converted Mustangs, of which there was only about 200, remain the most collectable in unmodified form. But not for me. I wanted something to drive and I was not prepared to live with vague steering and poor braking (fear not, I have saved all of the OEM parts).

RRS steering rack, no longer is the steering vague.

Upgraded brakes provide reassurance.

The DoT insisted I put the car on a dynometer to prove I was not making more than 20% power over normal (it cost me a new camshaft but that’s another story).

By the time I got the rubber to the road, I had an RRS manual steering rack, RRS coil-over front suspension, RRS front strut bracing and RRS disc brakes. The front and read subframes had been connected using aftermarket chassis rails produced for the purpose. I also increased the size of the sway bar from the standard 20mm to the larger 25mm. I may have made a mistake with the manual rack but, that aside, once on the move it feels responsive and reassuring. I did however make a major misstep with the engine.

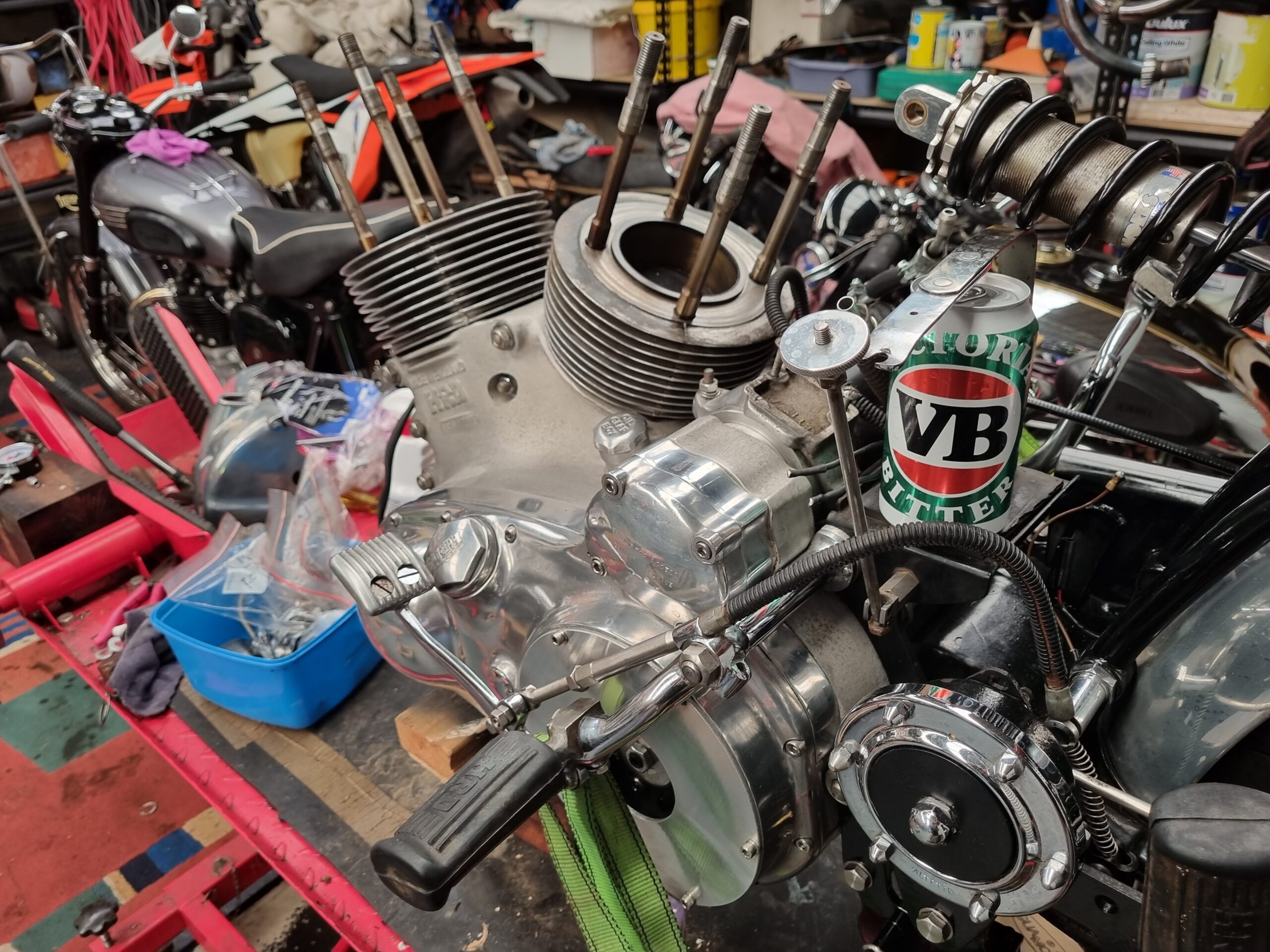

When I noticed a later (1985) roller-cam 5.0L engine pop up on the market I purchased it, as opposed to rebuilding the original 289. My engine guy built a very strong engine but when I declared the swap to the DoT, they started throwing around the term ‘high performance,’ and that’s when the fight started. The 5.0L engines were released with fuel injection and found their way into a variety of cars, including the Falcon GT. My car had no fuel injection and produced nowhere near the same power as the GT but the DoT err on the upper side of caution and if one variant produces x horsepower, then they all do! It was, for all intents and purposes a fairly standard Ford Windsor V8 engine commensurate with the era. My misstep was using an engine block from 1985, instead of one from the sixties, notwithstanding they were identical. I launched an appeal to DoT and got into a long stoush about the performance capabilities of my engine. Some of which is repeated here;

During the restoration, I learned of a 302 engine for sale in Perth that would negate the need for a complete rebuild to the extent I faced with the existing 289. The 302 engine, whilst still in the Windsor family of engines, proved to be one of the later model, “5.0 litre” blocks which had previously been fitted with fuel-injected. The engine was sold to me as having been ‘refurbished’ in the USA. It was always my intention to use only the short block with the, distributor, starter-motor, carburettor etc from the original car. As it transpired, the 302 required a full rebuild, the corollary being an engine that cost more than rebuilding the original 289 would have been but, by the time I learned that, I was deep into the rebuild and kept going. The car has undergone a preliminary examination by a DoT gazetted engineer. During the examination the engineer said a dynameter report would be required to show the transposed engine was not creating more than 20% of the original power output. The resultant report proved this to be the case.

I had a win but the whole argument was pointless. The dyno report proved the engine did not belong in the high-performance (LA2) category of engines that should have been the end of it. I had to fight the decision as the list of safety upgrades required for the later engine (see below) was completely unreasonable and, in some of the items, unachievable. As I said above, the car had been through engineering and found to be properly constructed, safe and compliant with Australian Design Rules of the era. What I was fighting was the unreasonable assertion my engine was ‘high-performance’ was therefore elevated the car into some unachievable level of finish. I had some very good people in my corner, Graham Billington for one. Had I lost the fight, I would have been consigned to refitting the 289 and running it through licensing with that engine (and possibly even having to revert back to the original steering, brakes and suspension). In hindsight, I should have rebuilt the 289 in the first place. It would have saved so much grief.

Looks like a Windsor duck, walks like a Windsor duck, quacks like a Windsor duck. Must be a Windsor. The Dept of Transport agreed however they also deemed this engine ‘high-perfomance.’ Of course, it was no such thing. Swept volume and dynmeter testing proved as much. Note also the RRS bracing which also had to have engineering approval.

This picture shows the sub-frame connectors being set in place. These pieces link the front and rear sub-frames and give the car extra rigidity.

August 2016. During the refit process, a professional photographer came into my shed and took a few pics. This remains one of my favourites. Thankyou Graham Hay.

Even after the car had been through engineering, it still had to be trailered to Perth for examination. I entered into another long, drawn out battle with the DoT over being able to have my car examined locally. I lost that fight.

On a final note. All of the OEM items remain under my bench with the engine. All the steering, suspension, brakes and braces have been retained for posterity. The hammer-blows of the people carrying out the conversion remain on the shock-tower and chassis rail, as does the quirky, left-hand wiper swipe and the forward-mounted brake booster. If a future owner wants to return the car to the form in which it left the Ford Australia Homebush facility, he or she will be able to do so. In the meantime, I’ll be out there putting the old girl through her paces (as they said in 1966).

The following is a list of requirements I had to meet to allow the car to pass examination;

The Consulting Engineer or Signatory report is to address the following items:

- Consultant to confirm the correct engine number as stamped on the engine block by the manufacture.

- Due to the engine fitment a Mandatory Upgrade of Safety Equipment will be required to include:

- Seatbelts to be installed to all seating positions – retractable lap sash to outer seating positions and lap seat belts to centre seating position.

- Split or dual braking system.

- Windscreen washers.

- Two speed windscreen wipers.

- A windscreen demister.

- Flashing direction indicator lights must be fitted at the front and rear of the vehicle.

- A collapsible steering column must be fitted.

- Fitment and suitability of the (year to be supplied) Ford 5.0-litre V8 naturally aspirated petrol engine in regard to complying with Section LA2 of VSB 14.

- Confirmation of the swept volume of the engine is required. Swept volume test to be sighted by the signatory and results including bore and stroke dimensions to be supplied.

- Fitment and suitability of any modifications to the engine including camshaft, fuel injectors, throttle body, air intake and any ECU programming complying with Section LA4.

- Signatory to provide evidence and engine specifications at time of test to certify that the maximum engine power does not exceed the 180 Kw per tonne power to weight ratio based on the heaviest variant of a 1966 Ford Mustang Sedan.

- A Dynamometer report on the maximum power and torque produced at the wheels after modification is to be supplied. The report must include VIN, engine number, maximum power and torque to be signed and supplied by Consulting Engineer or Signatory to prove compliance. Note: The report must list maximum torque and power on the Y- axis and engine rpm on the X-axis.

- Special consideration should be given to the extra weight applied to the front axle to ensure the manufacturers load capacity is not exceeded.

- The modifications to the exhaust system must comply with Section LA including LT4 (Noise Test) of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the Ford C4 automatic transmission complying with Section LB1 of VSB 14.

- Verification that the speedometer has been tested (and recalibrated if necessary) to the applicable ADR or where no ADR is applicable an accuracy of +10% or – 0.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the body/chassis modifications including engine and transmission mounting and fitment complying with Section LH of VSB 14.

- The total body/chassis structure and driveline being capable to sustain all of the stresses that is likely to be experienced by all of the proposed modifications.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the right-hand drive steering conversion complying with Section LS1 and LS2 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the RRS Rack and Pinion Steering conversion complying with Section LS4 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the modified suspension complying with Section LS of VSB 14.

- Evidence is required to verify the suspension travel is not reduced by more than one third of the manufacturer’s specifications.

- Special consideration should be given to ensure regulated height and ground clearance requirements are met.

- The consultant’s report is to supply the OEM and modified eyebrow and roof height dimensions.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the body/chassis modifications including chassis strengthening complying with Section LH of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the modified braking system (if other than total OEM option) complying with Section LG1 & LG2 of VSB 14.

- A brake test will be required for this vehicle as per LG1 Design Approval, refer to Table LG4 of VSB 14.

- Fitment, capability and suitability of the wheel track, wheels and tyres complying with Section LS of VSB 14.

- The wheels and tyres specified in your application appear not to comply with the LS section of VSB14 (overall width & diameter) and therefore are unacceptable. The LS section of the code fully explains the requirements. It is suggested that VSB14 be referred to and consultation with an Engineer to select wheels and tyres that meets the requirements of VSB14.

- A weighbridge docket verifying the vehicle TARE weight is required.

- The total body/chassis structure and driveline being capable to sustain all of the stresses that is likely to be experienced by all of the proposed modifications.

- Any other test or report that the consultant may consider necessary to prove conformity and safety of the modifications.

Please Note: Any modifications that are performed to the vehicle, additional to the original application will require a complete, new modification application to be submitted for re assessment. 5 of 6 Vehicle Safety and Standards 34 Gillam Drive Kelmscott 6111 Telephone (08) 92168579. Email: tps@transport.wa.gov.au

Note: This letter and the copy of your application are to be shown to your Consulting Engineer or Signatory, so he is aware of the items to be addressed.

Consulting Engineer or Signatory report is required to coincide with the application submitted by owner or agent. Time delays will be incurred, and the possibility of a new application will be required for the modifications by the owner or agent.

- Approval in principle to modify is granted at this point; however final acceptance cannot be completed until an acceptable report is submitted to DoT, Vehicle Safety and Standards Section for assessment and approval.

- This approval in principle for modification of the vehicle is valid for two years from the date of this letter; the Technical Policy and Services Coordinator must approve any further extension of time in writing.

- The report must include the name and address details of the applicant, vehicle details e.g. Make and Model, Year, engine, transmission, vehicle identification number, engine number and the Vehicle.

Special thanks must go to Graham Billington of Ultimate Automotive in Bunbury who came to the rescue when, having received the above letter, I tossed my toys out of the cot and and threatened to sell the finished car – unlicensed. Graham called me and, through the art of gentle persuasion, made me realise I had come too far to give up. I’m glad I persevered, thanks Graham. Now I’m off to find ten vestal virgins.

The car is registered on the WA Concessions for Classics (C4C) licensing scheme. This is much less restrictive than the former (404) scheme and allows us to use the car for special treats – such as a date night at a local restaurant.

Shoulda put a Hemi in it ……. Better still ….. Shouda restored a Plymouth , with the stock twin carb crossflow Hemi

My other car has a 6.4 ltr Hemi and it is more economical than the Mustang.

Are you out of your mind? Would you put a Fiat engine in your Cuda? Of course you wouldn’t!?

A great rebuild of a much-desired pony car. Properly rebuilt with decent steering and a few herbs added and the bonus is it looks fantastic. Full marks for dealing with the DoT finger-waggers and keeping your sanity but I guess they won’t ever know the feeling of reaching for the keys on a Saturday morning.

Thanks Chris. Nice to know I’m still sane!