The hill climb is one of the oldest forms of motorsport and it is making a comeback.

I was lucky enough to compete in two hill climbs during 2018. Designated vintage motorcycle hill climbs, the term ‘vintage’ simply means over 25 years old. Obviously, by 1993 motorcycles had reached epic proportions of speed and reliability and to term bikes as vintage merely because they are over 25 years is stretching the definition and unleashing a turbo-charged 1000 cc Kawasaki, for example, is probably not in the spirit of vintage hill climbs. Having said that, I’m happy to report just about every one of the 85 entrants at the Albany event was manufactured before 1980 with the majority from the fifties and sixties. Likewise the York Hill Climb.

York wasn’t my finest hour. The Triton was running super-rich and oiling up the left cylinder to the point at which it was fouling the plug (bearing in mind this is single carb engine). I managed to pull some half decent times which was mainly due to the short course but about halfway through the run my engine would begin to misfire. It didn’t lessen my fun or excitement but I felt the engine, in not running at is optimum, was an insult to my tuning skills – which are limited anyway. All I had to do was get the bike through the event because here was a fix at hand: in England.

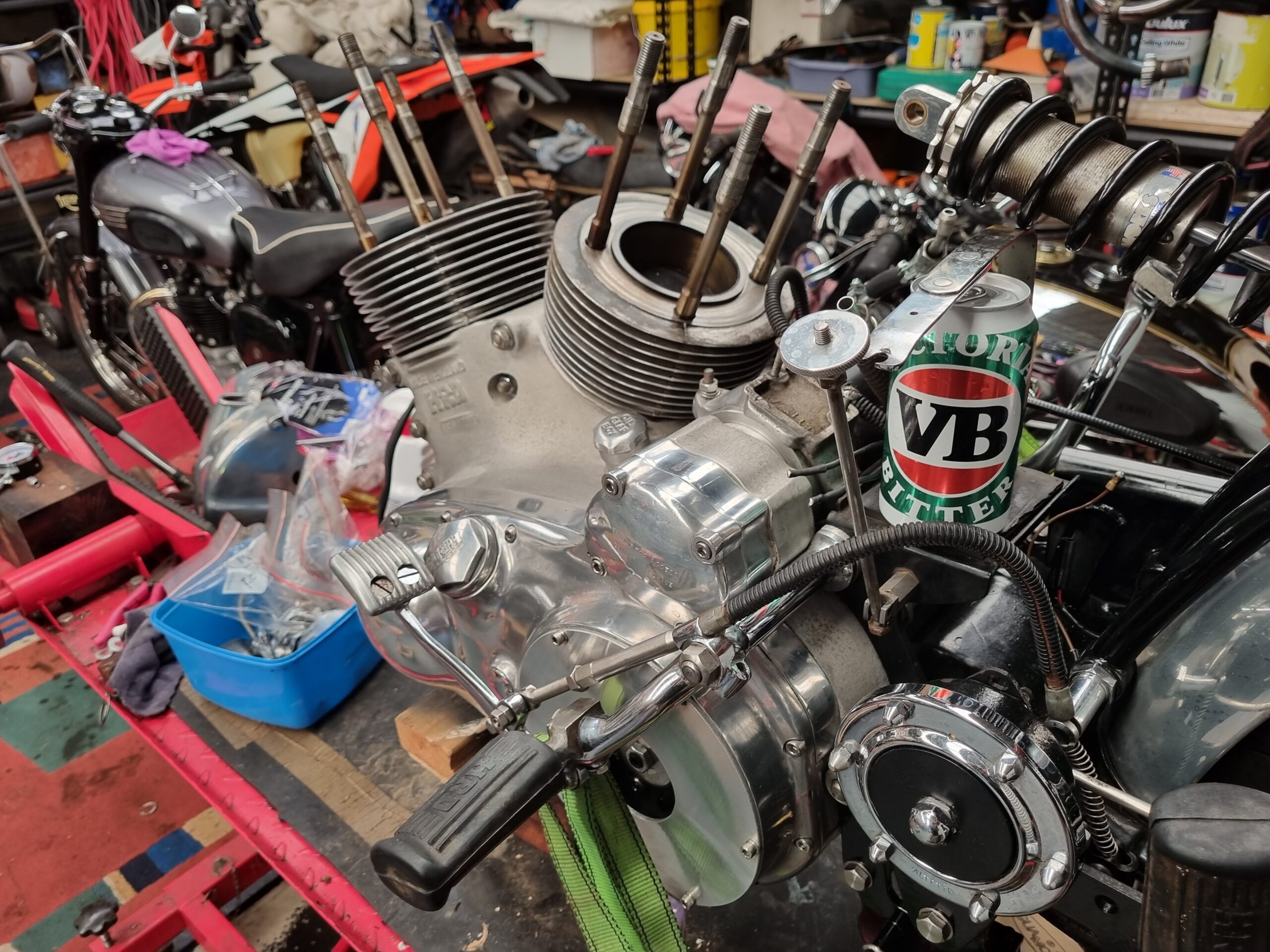

In June, whilst visiting the UK, my wife and I called in on the Morgo factory in Bradford where I picked up a new, big-bore 750cc barrel and pistons which would punch my Triton out by 100cc. I had purposefully kept my baggage to around 15 kilograms which would allow the weight of a full Morgo pistons and barrel kit. And two new Norton mufflers – but that’s another story. I didn’t need to go to the factory, I could have ordered the gear online but my bikes have so much Morgo gear tucked away their engines I kind of felt compelled to visit the place were the magic happens. I’m glad I did. My kit was packaged, waiting for me and the owner was touched that someone from Australia was visiting her business. Lynn, the owner of Morgo is the daughter of the late founder of the company and has been running things for the past four years since the passing of her father and by all accounts doing a fine job of things.

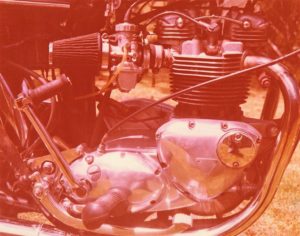

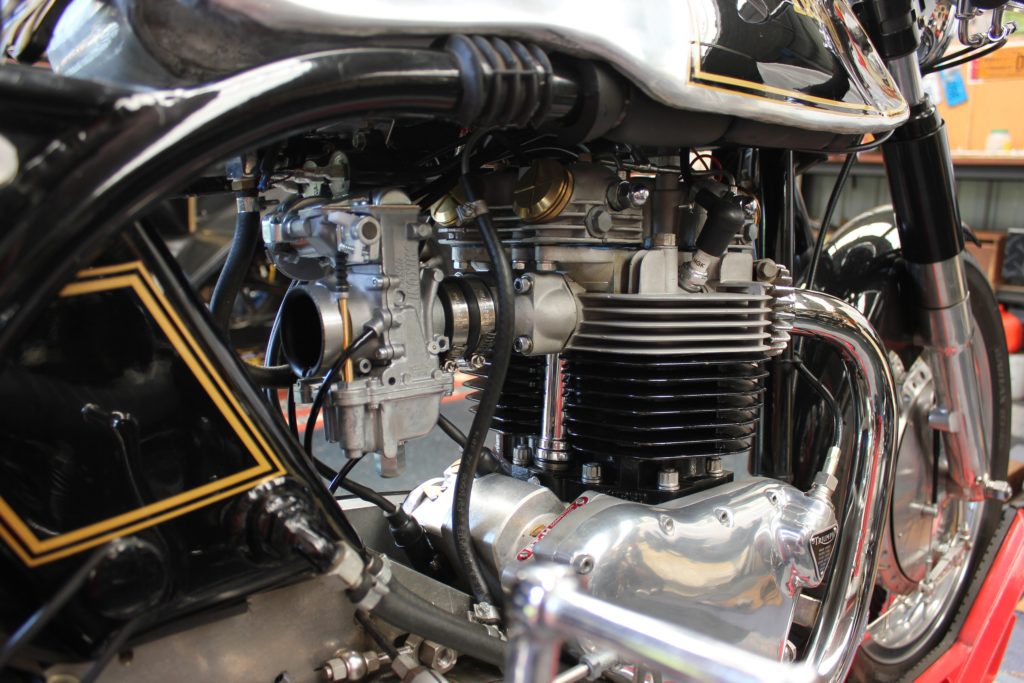

Morgo = more go! The 750 cc big-bore kit goes in, giving me 100 extra cc and Morgo bragging rights.

Extra cubes are all very well but they must be fed. Recall my comment above about not being all that well versed in motorcycle engine tuning? In rebuilding my Triton, I decided to retain the original single carb, 9-stud alloy head – as opposed to going to twin cards. To that end, I bought a new 36mm flat-side Mikuni carb from Mikuni Oz in Queensland. The Mikuni is a pumper style carb so it gives the engine an extra squirt of petrol when it’s most needed, i.e. when you crack the throttle.

Now there’s two types of people in classic motorcycle circles, Amal people and Mikuni people. I’m in the latter camp. The combination of the big-bore kit and the big pumper carb has my Triton running very sweetly so I’m willing to trade tiny bit English tradition for a big boost of Japanese performance.

My first big road bike was a 1977 Triumph Bonneville 750. The engine benefited enormously by fitting some larger, Mikuni carbs. Unfortunately the extra power was too much for the gearbox and I twisted the gearbox mainshaft in two. Twice.

I’ve yet to get the bike onto a dyno but for normal riding the Triton sounds and feels just like my first big road bike, a 1977 Bonneville which I bought new. In those days, incremental gains of one or two horsepower here and there seemed colossal in our never-ending search for more power and speed. It was like we were duty-bound to keep fettling the engine of our bikes to the point of blowing them up. After about two years of Bonneville ownership I fitted twin Mikuni carbs to the bike and had the inlet ports ground out to suit. The Bonny was transformed and for a brief time I enjoyed a healthy dose of horsepower – before I twisted and broke the gearbox main-shaft, twice. But I digress.

The Mikuni TM 36 pumper carb helps feed the 750 cc engine, bringing my Triton up to the same specs as the Bonneville I owned as a teenager. Mikuni Oz are in North Queensland and I recommend anyone struggling with tied, worn-out carbs to get in touch with Tom

By the time we got to Albany I figured I had the Triton well and truly sorted. Not so. The midrange was a bit flat but if I kept the reeves up high the engine hauled me up Mount Clarence in no short order. On my first run the bike almost cut out at the start line when it grabbed a great gulp of fuel and swallowed it whole. After a splutter, the engine took hold and launched me off the start line but it wasn’t enough to catch the Honda 750/4 that I was lined up against. I had much more success on the following three runs up against a Manx Norton. Before that however, I trundled off towards town and found a suburban hill, devoid of cars and shattered the Sunday morning peace whilst practising my hill starts half a dozen times. Satisfied I had perfected the art of the start, I returned to the hill climb to take on the Manx.

The legendary Manx is a highly-strung, highly geared, 500cc racing bike, not designed for drag racing up a hill but it’s oh so gorgeous and sounds sublime. I felt very privileged just to line up against a Manx so it was with some guilt that I beat it up the mountain on the three runs we shared. I felt even more guilty when the owner of the Manx sought me out specifically to offer to purchase my bike. I’ve had a few people offer to buy my Triton but I’ve yet to cave in to any offers and the Triton remains in the Motorshed garage.

My Triton shares its heritage with the Manx in the Featherbed frame made famous by Norton. Even the name is a contraction of Triumph and Norton. There is a story elsewhere on the Motorshed site as to how the Triton came into being which can be read here (https://motorshedcafe.com.au/the-triton/).

Alongside each other the bikes looked very similar. Naturally the Norton gives 250cc away to the Triumph engine in my bike but they both have a top speed of around 110 to 120 mph. The Norton gets there through a high state of tune and tall gearing, and that’s where I got the jump. The larger engine has more torque and therefore is able to get off the line quicker and climb better.

Both machines have an aggressive racing stance with a long reach to the clip-on handlebars and both were ridden by middle-age men who may not have been as flexible and subtle as we once were. Nevertheless, stretching out over the tank or a racing motorcycle allows a brief fantasy into the world of yesterday’s motorcycle racing champions, a feeling that is increased manyfold when we get to opportunity to actually race those bikes.

My practice starts revealed I could overcome the flat midrange by grabbing heaps of throttle at the start and riding the clutch to maintain the revs through first gear. Once in second gear with the throttle pegged, then again in third, the Triton came alive. When cranked into a sweeping righthand bend at full tilt, it never ceases to amaze me how Norton managed to design such a brilliant frame some 70 years ago. It feels rock solid and confidence-inspiring. In truth, the bike has much more to give but it would take a much better rider than me to explore limits of the Triton but, for now, I’m happy to make small gains in tunning, handling and, most importantly, riding ability.

The Triton and I, in our element. This photograph is by Andrew Haydock.

The perseverance, skinned knuckles and hours spent refining the bike over the past two years bore fruit on that day. At the top of the hill after each run I would join in with the other riders waiting to descend when the road was clear. Sitting up there, overlooking the bay with my engine clicking and clacking as it cooled, waiting for my adrenalin to return to normal levels, I was extremely happy with the performance of my ‘vintage’ motorcycle.

I reckon I’m ready to take it racing!

Photograph by John McKinnon.

Very valuable information, it is not at all blogs that we find this, congratulations I was searching for something like that and found it here.

Best regards,

Lunding Duke

Is this running this year November 2020?

I don’t think so Allan. It was difficult enough before Covid, now is has an extra label of complexity.